This is “Writing about the Natural World”, chapter 8 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 8 Writing about the Natural World

Learning Objectives

- Examine the concerns of scholars working to understand literary representations of the natural world.

- Apply ecocriticism to works of literature.

- Review works of poetry and fiction that explore the relationships between human beings and animals, plants, natural features, and natural phenomena.

- Learn how to revise an academic argument for clarity, persuasiveness, and stylistic grace.

- Draft and revise a critique of a work of literature based on environmental concerns.

8.1 Literary Snapshot: Through the Looking-Glass

Lewis Carroll, as we found out in previous chapters, is most famous for two books: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1872). These books follow the adventures of a seven-year-old, Alice, who tumbles down a rabbit hole (Wonderland) and enters a magic mirror (Looking-Glass), entering a nonsensical world of the imagination. If you have not already read these classic books—or wish to reread them—you can access them at the following links:

http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html

In Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice meets the twins Tweedledum and Tweedledee, who recite the following poem. It’s a long poem (as Alice worries it will be), but the episode is worth reading in full:

“What shall I repeat to her?” said Tweedledee, looking round at Tweedledum with great solemn eyes, and not noticing Alice’s question.

“‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ is the longest,” Tweedledum replied, giving his brother an affectionate hug.

Tweedledee began instantly:

“The sun was shining—”

Here Alice ventured to interrupt him. “If it’s very long,” she said, as politely as she could, “would you please tell me first which road—”

Tweedledee smiled gently, and began again:

“The sun was shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright—

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.

The moon was shining sulkily,

Because she thought the sun

Had got no business to be there

After the day was done—

‘It’s very rude of him,’ she said,

‘To come and spoil the fun!’

The sea was wet as wet could be,

The sands were dry as dry.

You could not see a cloud, because

No cloud was in the sky:

No birds were flying overhead—

There were no birds to fly.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

‘If this were only cleared away,’

They said, ‘it would be grand!’

‘If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year,

Do you suppose,’ the Walrus said,

‘That they could get it clear?’

‘I doubt it,’ said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear.

‘O Oysters, come and walk with us!’

The Walrus did beseech.

‘A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach:

We cannot do with more than four,

To give a hand to each.’

The eldest Oyster looked at him.

But never a word he said:

The eldest Oyster winked his eye,

And shook his heavy head—

Meaning to say he did not choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But four young Oysters hurried up,

All eager for the treat:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat—

And this was odd, because, you know,

They hadn’t any feet.

Four other Oysters followed them,

And yet another four;

And thick and fast they came at last,

And more, and more, and more—

All hopping through the frothy waves,

And scrambling to the shore.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Walked on a mile or so,

And then they rested on a rock

Conveniently low:

And all the little Oysters stood

And waited in a row.

‘The time has come,’ the Walrus said,

‘To talk of many things:

Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax—

Of cabbages—and kings—

And why the sea is boiling hot—

And whether pigs have wings.’

‘But wait a bit,’ the Oysters cried,

‘Before we have our chat;

For some of us are out of breath,

And all of us are fat!’

‘No hurry!’ said the Carpenter.

They thanked him much for that.

‘A loaf of bread,’ the Walrus said,

‘Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed—

Now if you’re ready Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed.’

‘But not on us!’ the Oysters cried,

Turning a little blue,

‘After such kindness, that would be

A dismal thing to do!’

‘The night is fine,’ the Walrus said

‘Do you admire the view?

‘It was so kind of you to come!

And you are very nice!’

The Carpenter said nothing but

‘Cut us another slice:

I wish you were not quite so deaf—

I’ve had to ask you twice!’

‘It seems a shame,’ the Walrus said,

‘To play them such a trick,

After we’ve brought them out so far,

And made them trot so quick!’

The Carpenter said nothing but

‘The butter’s spread too thick!’

‘I weep for you,’ the Walrus said.

‘I deeply sympathize.’

With sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of the largest size.

Holding his pocket handkerchief

Before his streaming eyes.

‘O Oysters,’ said the Carpenter.

‘You’ve had a pleasant run!

Shall we be trotting home again?’

But answer came there none—

And that was scarcely odd, because

They’d eaten every one.”

“I like the Walrus best,” said Alice: “because you see he was a little sorry for the poor oysters.”

“He ate more than the Carpenter, though,” said Tweedledee. “You see he held his handkerchief in front, so that the Carpenter couldn’t count how many he took: contrariwise.”

“That was mean!” Alice said indignantly. “Then I like the Carpenter best—if he didn’t eat so many as the Walrus.”

“But he ate as many as he could get,” said Tweedledum.

This was a puzzler. After a pause, Alice began, “Well! They were both very unpleasant characters—”Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (New York: Macmillan, 1899; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1993), chap. 4, http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html.

We might interpret the poem didactically: as a warning to children not to trust strange adults, for instance. The “eldest Oyster” refuses to follow the Walrus and the Carpenter, and he, unlike his siblings, isn’t eaten. Indeed, the poem was probably meant to mimic or even parody didactic children’s literature from the nineteenth century. It’s recited by Tweedledum and Tweedledee, after all, who “looked so exactly like a couple of great schoolboys” and who recite poems with great vigor, as if eager to please a teacher.

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Through the LookingGlass and What Alice Found There (1872).

There’s another possibility here, however. We can read this episode as a commentary on human beings’ relationships with the natural world. Look at the way the Walrus and Carpenter discuss the beach they’re walking on: “They wept like anything to see / Such quantities of sand: / ‘If this were only cleared away,’ / They said, ‘it would be grand!’” They wish to clear away the sand—to alter the landscape to suit their whims. That landscape is already altered: “You could not see a cloud,” the poem relates, “because / No cloud was in the sky.” What’s more, “No birds were flying overhead— / There were no birds to fly.” The natural world is marked by absence in this poem, and its two central characters weep because they cannot remove the sand from the seashore. Reading through the lens of environmental or ecocriticismA school of literary criticism that studies the depiction of the physical environment in works of literature. Ecocriticism often focuses on the way literary works depict human attitudes toward and interactions with the natural world., we might interpret these characters as representatives of human disregard for nature.

Such a reading might also help us understand the Walrus’s and the Carpenter’s treatment of the Oysters. They don’t simply trick the Oysters for sustenance—they gorge themselves, eating every one. They need “another slice” of bread, thickly spread butter, and “pepper and vinegar besides.”

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Through the LookingGlass and What Alice Found There (1872).

Look at the illustration of this scene: you see the Carpenter looking a little sick from overeating, and oyster shells strewn all around the beach like litter. It’s a scene of excess, of ill restraint. After hearing this story, Alice can’t decide which character was most unpleasant—the Walrus, who consumed the most oysters, or the Carpenter, who seemed unrepentant for his deceit. Alice, then, sees two moral problems in what the Walrus and the Carpenter do in the poem. First, she rejects their lack of sympathy for the Oysters, and second, she rejects the wastefulness of their consumption. In the end, Alice simply decides, “Well! They were both very unpleasant characters.” Part of what makes them so unpleasant, an ecocritic might suggest, is that they view the natural world and its creatures as theirs to exploit, with no repercussions or responsibilities on their part.

8.2 Ecocriticism: An Overview

Literary critics have long been interested in the way the natural world influences literary expression. For instance, in his important 1964 book The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, Leo Marx demonstrated that a “pastoral ideal” guided the formation of American culture, identity, and literature. This “urge to idealize a simple, rural environment,” Marx argues, continued even as America became “an intricately organized, urban, industrial, nuclear-armed society.”Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). Marx sees much of American literature as a response to this tension between urban realities (“the machine”) and pastoral ideals (“the garden”). Many other literary critics who wrote before the advent of a formal ecocritical school investigated similar topics, particularly when they studied authors who write frequently about nature, such as the Romantics of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The term RomanticismA movement of artists, writers, and philosophers during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Continental Europe, England, and the United States. Romantic thinkers and writers idealized emotional experiences and the natural world, eschewing many of the scientific, industrial, and capitalistic ideals that had come to define their societies. doesn’t have anything to do with steamy love scenes. Instead, Romanticism was an intellectual movement that idealized emotional experiences and the natural world, eschewing many of the scientific, industrial, and capitalistic ideals that had come to define society between, roughly, 1800–50. The following oil painting, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), by the German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich demonstrates the Romantic position. The painting can be interpreted in a variety of ways. An ecocritical reading might examine humanity’s relationship to nature—a human’s desire to appreciate the sheer power of the natural world—yet there seems to be a suggestion that the man, with his walking stick, is also contemplating the way to harness this power of nature, to civilize the natural world.

Painting by Caspar David Friedrich, The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818).

To get a better sense of these concerns, let’s look at “The World Is Too Much with Us,” a poem written by one of the most well-known Romantics, William Wordsworth.William Wordsworth, “The World Is Too Much with Us,” Poets.org, http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15878. It was published in 1807.

“The World Is Too Much with Us” by William Wordsworth

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers,

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.—Great God! I’d rather be

A pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

Your Process

- What do you think Wordsworth means by “the world” in this poem? How is “the world” distinct from “Nature”? Why do you think Wordsworth splits these two ideas apart? Record your thoughts.

- A related question: Why do you think Wordsworth capitalizes “Nature” and “Sea” in the poem? What other words are capitalized, and how might they relate to these two words? Jot down your ideas.

For a critic interested in literature and nature, Wordsworth’s poems are rich territory. In “The World Is Too Much with Us,” the speaker worries that people “lay waste” their “powers” because they are too wrapped up with “getting and spending.” In other words, the concerns of industry and commerce have crowded out those things that the speaker believes give human beings their power. We can read “the world” in the poem as the constructed world of human cities and concerns; that world “is too much with us” while the natural world has become estranged from humanity. “Little we see in Nature that is ours,” the speaker worries, and “we are out of tune” with “this Sea,” “the moon,” and “the winds.” By claiming that human beings have fallen out of tune with nature, the speaker implies that humanity was once in tune with it. The poem mourns a profound loss for men and women, who can no longer feel the emotions that bucolic natural scenes should evoke in them: “It moves us not.”

In the final lines of “The World Is Too Much with Us,” Wordsworth’s speaker wishes he could trade his modern existence for a more primitive life that is closer to nature. “Great God!” he exclaims, “I’d rather be / a pagan suckled in a creed outworn.” In other words, while the speaker does not believe in, say, the Greek myths—he insists that such religions are “outworn”—he would nonetheless trade his more modern ideas for a faith that allowed him to see the divine in the natural world. Keep in mind the Greek myths, in which each aspect of the natural world is overseen by a god or goddess, and in which many plants, animals, and natural features are said to embody mythical heroes or monsters. Wordsworth’s speaker wishes he could, when looking at the ocean, see more than water. He wishes he could see also “Proteus rising from the sea” and “hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.” Were he able to recognize the divinity of nature, the speaker insists, he would be “less forlorn” about his life in the modern world.

Whether they wrote during the Romantic period or not, writers who focus explicitly on nature in their works (e.g., John Keats, Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, and Annie Dillard) lend themselves well to this kind of analysis. However, modern ecocritics have expanded their focus to include much writing that’s not explicitly about nature. Ecocritics are interested in the attitudes that literary works express about nature, whether those attitudes are expressed consciously through the themes or plot of a work or unconsciously through the work’s symbols or language (for a thorough explanation of the unconscious, see Chapter 3 "Writing about Character and Motivation: Psychoanalytic Literary Criticism"). Even a work set in a city—the most urban of spaces—can nonetheless convey ideas about the loss of nature. Ecocritics can discuss the absence of nature in a work as well as its presence.

One could argue that a key turning point was the Industrial Revolution, which transformed the way people lived in worked in the nineteenth century. Moving from an agrarian or agricultural model to one centered on industry, the Industrial Revolution further reinforced the divide between the city and the country. Here are a few opening paragraphs from Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1852–53):

London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little 'prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon and hanging in the misty clouds.

Gas looming through the fog in divers places in the streets, much as the sun may, from the spongey fields, be seen to loom by husbandman and ploughboy. Most of the shops lighted two hours before their time—as the gas seems to know, for it has a haggard and unwilling look.

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation, Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

Never can there come fog too thick, never can there come mud and mire too deep, to assort with the groping and floundering condition which this High Court of Chancery, most pestilent of hoary sinners, holds this day in the sight of heaven and earth.

Dickens’s famous first sentence—“London.”—sets the action in London, where the mud and fog overpower the city. Dickens uses the “filth” of London as a symbol for the corruption of Chancery, the court system of London, but he’s also depicting a London that is diseased by industrialization—the fog, in particular, reflects the poor air quality of London during this time as coal-powered factories spewed their smoke over the city.

In America, writers also focused on the environment and the dangers of industrialization. Two famous examples are Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854), which you can read at http://thoreau.eserver.org/walden00.html, and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Nature” (1836), which you can read at http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl302/texts/emerson/nature-emerson-a.html #Introduction. Thoreau and Emerson, in fact, are two of the earliest ecocritical voices in America, and their influence was significant. Emerson and Thoreau argued that experiences in nature were the most authentic in human existence, and they urged their countrymen and women to go into the natural world for inspiration. Those ideas continue to inform literature to this day but also more tangible aspects of our lives, such as the dedication of so many communities to creating green spaces—parks, greenways, or river walks—for their citizens. Let’s look at a classic example, Rebecca Harding Davis’s 1861 short story, Life in the Iron Mills.

Your Process

- As we’ve suggested throughout this text, these process papers will make more sense if you are familiar with the literary work under discussion. For this section, you should read Rebecca Harding Davis’s short story, Life in the Iron Mills, which you can find in full as an e-text provided by Project Gutenberg (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm) and as a free audiobook provided by Librivox (http://librivox.org/life-in-the-iron-mills-by-rebecca-harding-davis/).

- As you read the story, keep a running list of all the references you find to the natural world. You can list natural features described, discussions of the characters’ attitudes toward nature, or anything else that seems to comment on humanity’s relationship to its environment.

- You might also be interested to look at the magazine in which Life in the Iron Mills originally appeared: The Atlantic for April 1861. You can find this historical text for free at the Internet Archive (http://archive.org/details/atlantic07bostuoft). Harding Davis’s story appears on page 430. Look at the articles that appear around this short story—how might those contexts help you build a “thick description” of Harding Davis’s text? For more on “thick description,” see Chapter 7 "Writing about History and Culture from a New Historical Perspective".

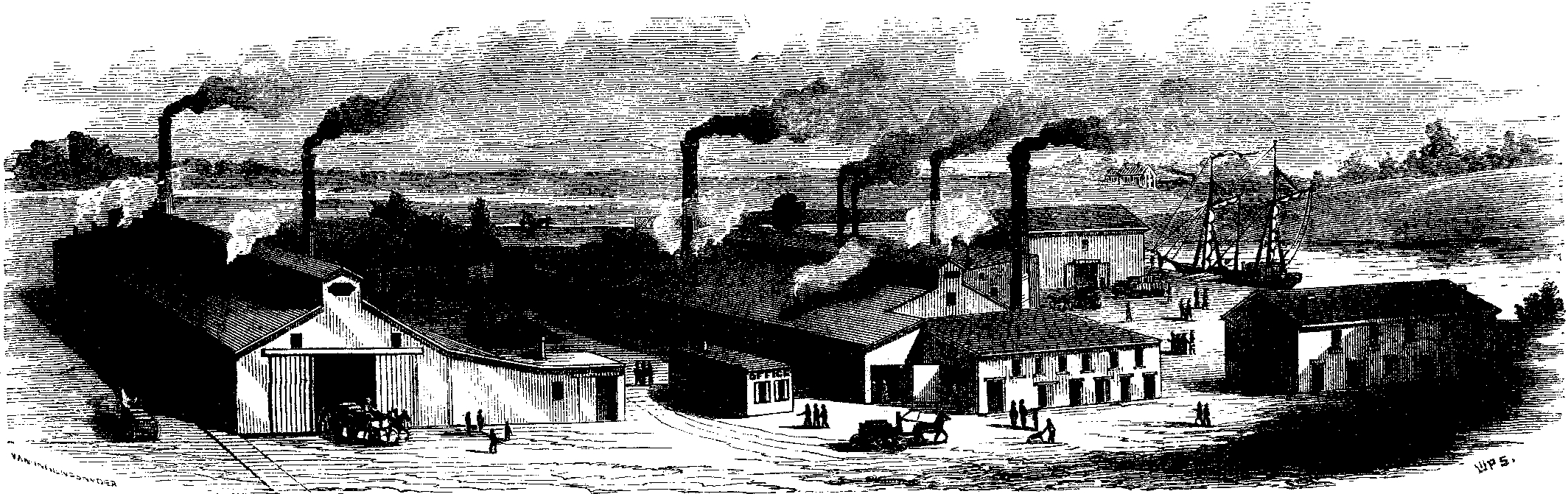

Illustration from “Wilmington and Its Industries,” Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science (April, 1873).

Life in the Iron Mills recounts a story of Welsh immigrants working in an iron-mill town along the Ohio River in an area that would become West Virginia. Readings of this story often focus on its critique of industrialization and capitalism. For instance, a critic might look at the ways that Hugh Wolfe’s artistic talents cannot flower in the story because of his class or ethnic background (see Chapter 5 "Writing about Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Identity" for ideas about how you might develop such a reading). Let’s look closely at the story’s opening paragraphs, however, with an eye to the text’s attitudes toward the environment and natural world.

A cloudy day: do you know what that is in a town of iron-works? The sky sank down before dawn, muddy, flat, immovable. The air is thick, clammy with the breath of crowded human beings. It stifles me. I open the window, and, looking out, can scarcely see through the rain the grocer’s shop opposite, where a crowd of drunken Irishmen are puffing Lynchburg tobacco in their pipes. I can detect the scent through all the foul smells ranging loose in the air.

The idiosyncrasy of this town is smoke. It rolls sullenly in slow folds from the great chimneys of the iron-foundries, and settles down in black, slimy pools on the muddy streets. Smoke on the wharves, smoke on the dingy boats, on the yellow river,—clinging in a coating of greasy soot to the house-front, the two faded poplars, the faces of the passers-by. The long train of mules, dragging masses of pig-iron through the narrow street, have a foul vapor hanging to their reeking sides. Here, inside, is a little broken figure of an angel pointing upward from the mantel-shelf; but even its wings are covered with smoke, clotted and black. Smoke everywhere! A dirty canary chirps desolately in a cage beside me. Its dream of green fields and sunshine is a very old dream,—almost worn out, I think.

From the back-window I can see a narrow brick-yard sloping down to the river-side, strewed with rain-butts and tubs. The river, dull and tawny-colored, (la belle riviere!) drags itself sluggishly along, tired of the heavy weight of boats and coal-barges. What wonder? When I was a child, I used to fancy a look of weary, dumb appeal upon the face of the negro-like river slavishly bearing its burden day after day. Something of the same idle notion comes to me to-day, when from the street-window I look on the slow stream of human life creeping past, night and morning, to the great mills. Masses of men, with dull, besotted faces bent to the ground, sharpened here and there by pain or cunning; skin and muscle and flesh begrimed with smoke and ashes; stooping all night over boiling caldrons of metal, laired by day in dens of drunkenness and infamy; breathing from infancy to death an air saturated with fog and grease and soot, vileness for soul and body. What do you make of a case like that, amateur psychologist? You call it an altogether serious thing to be alive: to these men it is a drunken jest, a joke,—horrible to angels perhaps, to them commonplace enough. My fancy about the river was an idle one: it is no type of such a life. What if it be stagnant and slimy here? It knows that beyond there waits for it odorous sunlight, quaint old gardens, dusky with soft, green foliage of apple-trees, and flushing crimson with roses,—air, and fields, and mountains. The future of the Welsh puddler passing just now is not so pleasant. To be stowed away, after his grimy work is done, in a hole in the muddy graveyard, and after that, not air, nor green fields, nor curious roses.

Can you see how foggy the day is? As I stand here, idly tapping the windowpane, and looking out through the rain at the dirty back-yard and the coalboats below, fragments of an old story float up before me,—a story of this house into which I happened to come to-day. You may think it a tiresome story enough, as foggy as the day, sharpened by no sudden flashes of pain or pleasure.—I know: only the outline of a dull life, that long since, with thousands of dull lives like its own, was vainly lived and lost: thousands of them, massed, vile, slimy lives, like those of the torpid lizards in yonder stagnant water-butt.—Lost? There is a curious point for you to settle, my friend, who study psychology in a lazy, dilettante way. Stop a moment. I am going to be honest. This is what I want you to do. I want you to hide your disgust, take no heed to your clean clothes, and come right down with me,—here, into the thickest of the fog and mud and foul effluvia. I want you to hear this story. There is a secret down here, in this nightmare fog, that has lain dumb for centuries: I want to make it a real thing to you. You, Egoist, or Pantheist, or Arminian, busy in making straight paths for your feet on the hills, do not see it clearly,—this terrible question which men here have gone mad and died trying to answer. I dare not put this secret into words. I told you it was dumb. These men, going by with drunken faces and brains full of unawakened power, do not ask it of Society or of God. Their lives ask it; their deaths ask it. There is no reply. I will tell you plainly that I have a great hope; and I bring it to you to be tested. It is this: that this terrible dumb question is its own reply; that it is not the sentence of death we think it, but, from the very extremity of its darkness, the most solemn prophecy which the world has known of the Hope to come. I dare make my meaning no clearer, but will only tell my story. It will, perhaps, seem to you as foul and dark as this thick vapor about us, and as pregnant with death; but if your eyes are free as mine are to look deeper, no perfume-tinted dawn will be so fair with promise of the day that shall surely come.Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills (1861; Project Gutenberg 2008), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm.

These first paragraphs detail the scenery of the narrator’s world (and notice the similarity to Dickens). In this case, however, the scenery described is obscured by the products of human industry. The natural world is obscured both figuratively (“The air is thick, clammy with the breath of crowded human beings.”) and literally, by smoke: “The idiosyncrasy of this town is smoke. It rolls sullenly in slow folds from the great chimneys of the iron-foundries, and settles down in black, slimy pools on the muddy streets. Smoke on the wharves, smoke on the dingy boats, on the yellow river,—clinging in a coating of greasy soot to the house-front, the two faded poplars, the faces of the passers-by.” The river, too, is polluted; it’s “dull and tawny-colored” and “tired” of the many “boats and coal-barges” bringing goods to and from the town. The town is so polluted that its human inhabitants suffer acutely, “breathing from infancy to death an air saturated with fog and grease and soot, vileness for soul and body.”

The ecocritic might interpret this story as a sustained critique of a modern society that disregards the needs of the planet in order to advance the narrow priorities of industrial and consumer culture. In order to produce iron, the material that shaped so much of the Industrial Revolution, the owners of the factories in this story have destroyed the air, the water, and even the health of the human beings who make their business run. In fact, they have made all of nature (including human beings) slaves to industry. The river is imagined as “slavishly bearing its burden day after day.” The men who work in the factories are so broken in spirit that they consider their lives “a drunken jest, a joke.” The narrator points out that far beyond this town one can find “odorous sunlight, quaint old gardens, dusky with soft, green foliage of apple-trees, and flushing crimson with roses,—air, and fields, and mountains.” These healthful natural features, however, are beyond the reach and understanding of those living in this “town of iron-works,” who are “stowed away, after [their] grimy work is done, in a hole in the muddy graveyard, and after that, not air, nor green fields, nor curious roses.” Harding Davis’s novella, then, draws an explicit parallel between human flourishing and human treatment of the natural world. When human beings disregard nature, Life in the Iron Mills implies, they suffer with nature.

What’s more, the narrator of Harding Davis’s story challenges the story’s readers to come to terms with the realities described in the novella. The original readers of this story would have been subscribers to the Atlantic magazine, which means they would likely have been educated, financially secure members of middle- or upper-class society. In other words, they would have been nothing like the iron workers Harding Davis writes of in the story and would not have experienced the absolute deprivation from nature the tale relates. Her narrator addresses this discrepancy directly:

There is a curious point for you to settle, my friend, who study psychology in a lazy, dilettante way. Stop a moment. I am going to be honest. This is what I want you to do. I want you to hide your disgust, take no heed to your clean clothes, and come right down with me,—here, into the thickest of the fog and mud and foul effluvia. I want you to hear this story. There is a secret down here, in this nightmare fog, that has lain dumb for centuries: I want to make it a real thing to you. You, Egoist, or Pantheist, or Arminian, busy in making straight paths for your feet on the hills, do not see it clearly,—this terrible question which men here have gone mad and died trying to answer. I dare not put this secret into words.Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills (1861; Project Gutenberg 2008), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm.

There’s a lot going on in these few sentences, but the ecocritic would likely concentrate on the way Harding Davis’s narrator insists that her readers must experience the horrible environmental conditions of her subjects in order to understand their story. Her readers must “take not heed to [their] clean clothes” and “come right down…into the thickest of the fog and mud and foul effluvia.” Readers “busy in making straight paths for [their] feet on the hills” cannot “see clearly” the plight of those who cannot spend time in the hills, experiencing the natural world without smoke and mud and effluvia.

These natural themes continue throughout Life in the Iron Mills. At the end of the novella, in fact, Deborah—one of the characters deformed, body and soul, by her time in the mill town—is taken in by Quakers who live in the hills near the town.If you’re unfamiliar with the Quakers, or the Religious Society of Friends, see this resource from the BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/subdivisions/quakers_1.shtml. The narrator reports that life in closer communion with nature purifies Deborah:

There is no need to tire you with the long years of sunshine, and fresh air, and slow, patient Christ-love, needed to make healthy and hopeful this impure body and soul. There is a homely pine house, on one of these hills, whose windows overlook broad, wooded slopes and clover-crimsoned meadows,—niched into the very place where the light is warmest, the air freest. It is the Friends’ meeting-house. Once a week they sit there, in their grave, earnest way, waiting for the Spirit of Love to speak, opening their simple hearts to receive His words. There is a woman, old, deformed, who takes a humble place among them: waiting like them: in her gray dress, her worn face, pure and meek, turned now and then to the sky.Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills (1861; Project Gutenberg 2008), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm.

Living in greater harmony with nature “make[s] healthy and hopeful” Deborah’s “impure body and soul.” The warm light, free air, “wooded slopes,” and “clover-crimsoned meadows” all contribute to her restoration. In the last view readers have of Deborah, she turns her face “now and then to the sky.”

Harding Davis’s Life in the Iron Mills can be read, then, as a searching critique of modern society without nature—a warning about what mass industrialization will do to the environment and the men and women who rely on it. You can probably see that these ideas relate closely to ideas one would find in modern environmentalistA modern philosophy and social movement dedicated to improving human beings’ interactions with the natural world, often through practices designed to mitigate damage that human beings have done to it in the past. Environmentalists advocate for restoration of natural spaces, conservation of natural resources, and control of practices that damage the natural world. thought. We can read Harding Davis’s story as an exposé of human practices that permanently scar the natural world—an argument against pollution and waste. In cases like this, we want to be careful of anachronismSomething placed in an incorrect time period. In literature, anachronism often refers to objects, ideas, phrases, or the like placed in historically inappropriate scenes. For instance, if a character in a story set during the Civil War (1861–1865) was described driving a car, we would call the car anachronistic.. Harding Davis wrote this work long before scientists and other thinkers articulated the ideas and principles of the modern environmentalist movement. We wouldn’t, for instance, want to discuss Life in the Iron Mills as advocating for recycling, a word and practice of which Harding Davis would never have heard. Nevertheless, we can point out sympathetic ideas between Harding Davis’s story and modern environmentalist concerns, drawing out nuances of the story that may not have been apparent to earlier readers.

Your Process

- After looking at these two examples, what seem to be the primary questions that ecocritics ask of literary works? In the notes box, make a list of priorities (i.e., things to look out for) for you to follow when you read as an ecocritic.

When you’re reading literature as an ecocritic, then, start by asking the following questions:

- How does this novel, story, poem, play, or essay represent the natural world (e.g., plants, animals, ecosystems)? Is nature portrayed positively, negatively, or otherwise?

- How does the work represent the relationship between human beings and nature? For instance, is the relationship symbiotic or adversarial?

- Do the characters in the work express ideas or opinions about their environment (whether a “natural” environment as in Wordsworth’s poem or a man-made environment as in Harding Davis’s story)? What cultural, social, or political values do characters seem to embody? When asking this question, don’t forget to consider the narrator!

- Does the text engage consciously with ideas related to modern environmentalism? For instance, does the text seem to make an argument for or against conservationism, preservation, or restoration?

8.3 Focus on Ecocritical Approaches: Ecofeminism and Darwinian Literary Criticism

Ecofeminism

As you may have guessed from its name, ecological feminism, or “ecofeminismCritical approach that focuses on the connections between human gender relations and humans’ relationship to the natural world. Ecofeminists critique both the oppression of women by men and the oppression of nature by humans.,” combines the ideas of ecocriticism with those of feminism (for an in-depth look at feminism, see Chapter 4 "Writing about Gender and Sexuality: Applying Feminist and Gender Criticism"). In other words, it is a form of feminism that critiques the oppression of nature as well as the oppression of women, and argues that our relationship to nature is a feminist issue. Ecofeminists explore the ways in which both women and the natural world are devalued and exploited by the patriarchal societies in which we live. They call attention to the way that women are seen as connected to nature, while men are conceptually linked to culture, and how these connections have been used to justify both the abuse of the environment and the oppression of women. As you can imagine, ecofeminism is heavily influenced by the “green” movement, or environmentalism, as well as by feminism; in fact, ecofeminism as a movement really developed in the 1970s and 1980s, alongside environmentalism and second-wave feminism.

Like other feminist critics, ecofeminists often take an intersectional approach in their analyses. IntersectionalityA theory frequently used in feminist analyses and in sociological studies that sees the various forms of oppression in a society—race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, religion, and so on—as being interconnected. It holds that because our identities are made up of a variety of markers, we each experience the matrix of oppression in a unique way. refers to a sociological theory that sees social inequalities as being interconnected and inseparable from one another. It explores how the various categories of identity—gender, sexuality, race, class, ability, religion, and so on—interact with one another to create the complex system of inequalities in society. As individuals, we experience this matrix of oppression in unique ways: for example, a gay African American man might experience his oppression in a very different way than a white lesbian experiences hers, though they are both affected by homophobia. Ecofeminism lends itself well to an intersectional approach since it already explores the intersection of two systems of oppression: gender inequality and the domination of humans over nature. In addition, some ecofeminists consider how the oppression of women and nature intersects with other forms of oppression. As Jens, the author of our first student sample paper in this chapter, points out, we could look at Disney’s Pocahontas through a variety of critical lenses: ecocritical, feminist, racial, ethnic, and cultural studies. An ecofeminist might use all these lenses in the same analysis!

Let’s revisit Rebecca Harding Davis’s Life in the Iron Mills to see how an ecofeminist approach to the story might differ from the ecocritical approach we took earlier. Here are the links to the story again:

E-text: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm

Audiobook: http://librivox.org/life-in-the-iron-mills-by-rebecca-harding-davis/

Harding Davis sets her story in “a town of iron-works,” where the character Hugh Wolfe works in a mill making railroad iron. While Harding Davis focuses on the hardships and oppression faced by those who work in the mills, an ecofeminist critic might point out that the first stage in the iron manufacturing process is the mining of iron ore from the earth. Mining is a highly problematic practice from an ecofeminist perspective, as it involves digging into the earth, removing materials that naturally belong underground, and disrupting ecosystems by destroying plant and animal life in the process. Furthermore, because we have historically gendered the earth as female (you may already be familiar with the image of “Mother Earth”), mining can be seen as parallel to—and even a justification of—sexual violence against women. As Carolyn Merchant explains in her influential ecofeminist text The Death of Nature (1980), mining used to be viewed as an unethical practice for this very reason—at least, until the Scientific Revolution from the sixteenth to eighteenth century changed our attitude toward nature. Merchant writes, “The image of the earth as a living organism and nurturing mother has served as a cultural constraint restricting the actions of human beings. One does not readily slay a mother, dig into her entrails for gold or mutilate her body, although commercial mining would soon require that. As long as the earth was considered to be alive and sensitive, it could be considered a breach of human ethical behavior to carry out destructive acts against it.”Carolyn Merchant, Reinventing Eden: The Fate of Nature in Western Culture (New York: Routledge, 2003).

“Digging into the matrices and pockets of the earth for metals,” she continues, “was like mining the female flesh for pleasure”—or, in more explicit terms, mining turned Mother Earth into “a passive receptor of human rape.”Carolyn Merchant, Reinventing Eden: The Fate of Nature in Western Culture (New York: Routledge, 2003). Although some would argue that it is not appropriate to compare mining the earth to raping human women, this parallel forces us to see mining in a new light: as a violation of the earth rather than as a human “right” to take whatever we desire from nature.

Our perceptions of Harding Davis’s Life in the Iron Mills are certainly altered when we add an ecofeminist dimension to our critique. Now, not only do we see how Harding Davis is responding to the oppression of the working class and the large-scale pollution that resulted from the Industrial Revolution; we also recognize that the iron mills exist because humans’ attitudes toward the earth changed dramatically just prior to the time when Harding Davis’s story is set. Hugh Wolfe can work in the iron mill because other men work as miners, enacting violence on the feminized earth. We can begin to see the matrix of oppression in this relationship: mining—an act of violence against nature that parallels violence against women through the gendering of the earth as female—leads to iron manufacturing, an industry in which rich individuals exploit and oppress members of the working class. In addition, the gendered division of labor in the town (Wolfe and other men work in the iron mill, while Deb and other women work in the cotton mill) and the pollution caused by the mills bring us, full circle, back to the oppression of women and of the environment. Thus, by simultaneously examining the treatment of women and the treatment of the natural world in an intersectional ecofeminist analysis, we can bring to light multiple forms of oppression at the same time—and begin to understand how they are related to one another.

Darwinian Literary Criticism

Also called literary Darwinism or Darwinian evolutionary literary criticism, Darwinian literary criticismLiterary method based on the belief that stories—that art in general—hold a key to human survival since storytelling or art making must provide an advantage for survival. grapples with a key notion: What is the adaptive value of literature and art to human survival? We can understand, for example, how humans evolved to create a spear for hunting since food is essential for survival. But what do we make of a spear that is ornately carved into a beautiful, artistic object? How does that art add to the adaptive survival value of a person or a species? Two questions central to Darwinian literary critics are the following: Why do humans tell stories? Do stories provide some genetic advantage in the pursuit of survival? Darwinian literary criticism examines literature, in particular, through the lens of evolutionary theory.

When Darwin published Origin of Species in 1859, he transformed the way we viewed the natural world. Darwin argued that humans—that all species—evolved from a common ancestor. Over time, species diversity developed according to four key principles, according to Darwin: (1) nature provides limited resources for survival, though there are more organisms than resources; (2) as a result, these organisms fight for survival (which became known as the “survival of the fittest”); (3) organisms pass on genetic traits to their heirs, though those traits that survive are the ones that have the greatest survival value; (4) those with the strongest genetic traits survive, while those who do not receive those traits become extinct. In this Darwinian scheme, why do humans continue to tell stories and make art? For Darwinian literary critics, the answer is that creating art must be a key survival trait.

For example, in 1813 Jane Austen published Pride and Prejudice, a story about the Bennett sisters who must make advantageous marriages so that they will be cared for. This novel, Austen’s most famous and well loved, is a popular love story elevated to high art. How might Darwinian literary critics read this love story? One way to interpret is to focus on biological survival. Elizabeth Bennett, for example, finally makes the best match by marrying the aristocrat, Mr. Darcy, and this marriage combines the best genetic traits of both lovers, which makes their survival more likely. How’s that to destroy a love story?!

While Darwinian literary criticism is a varied and complex field, a useful focus for you is to speculate how particular stories—specifically those that have survived the test of time—reflect core narratives of survival. Such stories may include mythic stories that provide humans with a way to bond together as a group, thus increasing the probability of survival. An interesting example of this comes from the field of fairy tale studies. Jack Zipes in Why Fairy Tales Stick and The Irresistible Fairy Tale argues that the classic fairy tales—“Cinderella,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Snow White,” or “Hansel and Gretel,” for example—replicate patterns of survival that are attractive to readers, providing them with strategies for survival.Jack Zipes, The Irresistible Fairy Tale: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012). Zipes evokes the theories of Richard Dawkins who, in The Selfish Gene (1976), argued for the idea of a memePattern of narrative that is culturally inherited, modified, and adapted. Memes become core narratives for cultural bonding and thus survival., “an informational pattern contained in a human brain (or artifacts such as books or pictures) and stored in its memory, capable of being copied to another individual’s brain that will store it and replicate it.”Jack Zipes, Why Fairy Tales Stick: The Evolution and Relevance of a Genre (New York, Routledge, 2006), 4. In other words, important stories that help with human survival are inherited, passed down, and replicated or transformed to meet a culture’s need for survival.

In The Irresistible Fairy Tale, Zipes provides a reading of “Hansel and Gretel,” a favorite tale found in the Brothers Grimm’s collection of fairy tales (which has inspired the popular television show Grimm). Zipes suggests that “Hansel and Gretel” evokes key issues about survival that continue to plague us—“the problems raised by the discourse in this tale have not been resolved in reality: poverty, conflict with stepparents, the trauma of abandonment, child abuse, and male domination.”Jack Zipes, The Irresistible Fairy Tale: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 220. Thus fairy tales continue to impact contemporary readers because the issues raised by the tales are central to human survival. The tales are also revised and adapted for contemporary readers to further show the relevancy of these unresolved issues.

Darwinian literary criticism is an evolving field (no pun intended) in literary theory, which may suggest that literary theory itself is an important meme for the survival of literature in the twenty-first century.

Your Process

- List your favorite fairy tale.

- List the key adaptations or retellings of the tale (Disney, for example).

- Write down reasons why you think this fairy tale is so important to you and what the adaptations have done to the original tale.

- Now connect this to Darwinian literary criticism: Does your fairy tale provide you with a technique for survival? Explain.

8.4 Writing about the Natural World: A Process Approach

To review, ecocriticism provides us with a particular lens to use when we read and interpret works of literature. Such reading and interpreting, however, never happens after just a first reading; in fact, all critics reread works multiple times before venturing an interpretation. You can see, then, the connection between reading and writing: as Chapter 1 "Introduction: What Is Literary Theory and Why Should I Care?" indicates, writers create multiple drafts before settling for a finished product. The writing process, in turn, is dependent on the multiple rereadings you have performed to gather evidence for your essay. It’s important that you integrate the reading and writing process together. As a model, use the following ten-step plan as you write using an ecocritical approach:

- Carefully read the work you will analyze.

- Formulate a general question after your initial reading that identifies a problem—a tension—related to a historical or cultural issue.

- Reread the work, paying particular attention to the question you posed. Take notes, which should be focused on your central question. Write an exploratory journal entry or blog post that allows you to play with ideas.

-

Construct a working thesis that makes a claim about the work and accounts for the following:

- What does the work mean?

- How does the work demonstrate the theme you’ve identified using a new historical approach?

- “So what” is significant about the work? That is, why is it important for you to write about this work? What will readers learn from reading your interpretation? How does the theory you apply illuminate the work’s meaning?

- Reread the text to gather textual evidence for support.

- Construct an informal outline that demonstrates how you will support your interpretation.

- Write a first draft.

- Receive feedback from peers and your instructor via peer review and conferencing with your instructor (if possible).

- Revise the paper, which will include revising your original thesis statement and restructuring your paper to best support the thesis. Note: You probably will revise many times, so it is important to receive feedback at every draft stage if possible.

- Edit and proofread for correctness, clarity, and style.

We recommend that you follow this process for every paper that you write from this textbook. Of course, these steps can be modified to fit your writing process, but the plan does ensure that you will engage in a thorough reading of the text as you work through the writing process, which demands that you allow plenty of time for reading, reflecting, writing, reviewing, and revising.

Peer Reviewing

A central stage in the writing process is the feedback stage, in which you receive revision suggestions from classmates and your instructor. By receiving feedback on your paper, you will be able to make more intelligent revision decisions. Furthermore, by reading and responding to your peers’ papers, you become a more astute reader, which will help when you revise your own papers. In Chapter 10 "Appendix A: Peer Review Sheets", you will find peer-review sheets for each chapter.

8.5 Student Writer at Work: Jens Paasen’s Ecocritical Paper in Development

Throughout most of this book, we’ve shown you exemplary student papers representing each school of literary criticism. In this chapter, we want to focus on how you can revise a paper to improve its organization and argument. In order to do this, we start with a paper written by Jens Paasen in his Introduction to Literature class. Jens focuses on a subject that might seem strange for a literature classroom: Walt Disney’s film, Pocahontas. In class, however, Jens and his classmates have concentrated on literary depictions of the natural world, and Jens believes this film could be interesting if looked at through an ecocritical lens. As Jens works through these ideas, he gets lots of new ideas about how ecocriticism could inform his argument. Watch the way Jens follows these distinct ideas in this first draft of his paper. At the end of the paper we will discuss how Jens made revisions with advice from his professor and peer colleagues.

Your Process

- As we’ve suggested throughout this text, these process papers will make more sense if you are familiar with the work under discussion. In most sections we’ve provided links to public, electronic editions of the texts under discussion. The film discussed in Jens’s paper, however, is still under copyright. The interpretive moves in the paper should make sense whether you’ve seen the movie or not, but we highly recommend that you watch the movie before studying the sample paper. You can rent or buy a digital copy of Disney’s Pocahontas online.

- As you read Jens’s paper, pay particular attention to the claims that Jens makes. Perhaps list his main claims on a separate sheet of paper. How many distinct ideas do you count?

Jens Paasen

Professor Laurie MacDiarmid

Introduction to Literature

March 3, 20–

Disney’s Pocahontas and Ecocriticism: Dualism, Anthropocentrism and Animals

1 Introduction and Theoretical Background

In June 1995 Disney released its 33rd animated feature. For the first time ever Disney based a film on actual historical characters and events. The legend surrounding one of the earliest and great American heroines served as a reference: the legend of the Indian princess Matoaka, better known as Pocahontas.

Since its release, the film has been considered from various perspectives. Critics especially found fault with the depiction of Native Americans and the figure of Pocahontas from a feminist perspective. However, the idea and function of nature in the film, apart from some exceptions, appears to be unconsidered. The following term paper wants to take a critical look at the idea of nature in the film and consider its depiction and function from an ecocritical perspective.

The setting of Pocahontas is the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Nature and wilderness are surely the single most dominating features of this setting. One of the very first things the character Captain John Smith notices when scouting the terrain is: “[…] a wilder, more challenging country I couldn’t design” (Pocahontas scene 11). Nature is omnipresent in the film and appears in various forms and functions.

This paper does not want to contribute to the debate about common points of criticism in Pocahontas. I think Russell Means, former head of the American Indian Movement and voice of chief Powhatan in the film, caused enough of a controversy when he called the film “The single finest work ever done on American Indians by Hollywood” (Gabriel and Goldberg). The right or wrong depiction of Native Americans is no more interesting for this work than the question of historical truth and authenticity. The parallelism between femininity and nature in the film will also not be considered as it is an issue of ecofeminism. Neither will the figure of Pocahontas be considered from a feminist perspective. The fact that the whole film, though portraying nature in a very spiritual and positive light, is based on a machinery of culture and capitalism, i.e. the Disney corporation, will not be considered, but should still be borne in mind. The paper will work exclusively intradiegetic in the world of the film and totally disregard outer factors. The following questions will be examined in the course of the paper. How are nature and culture presented as opposing concepts? How is nature instrumentalized to create anthropocentrism? How authentic are the animals presented in the film, and what functions do they have?

2 Disney’s Pocahontas

2.1 Some Introductory Words On Literal Determinism

One of the most important features of ecocriticism is that it denies what Peter Barry calls “the first item in the list of five recurrent ideas in critical theory”:

They turn away from the “social constructivism” and “linguistic determinism” of dominant literary theories (with their emphasis on the linguistic and social constructedness of the external world) and instead emphasize ecocentric values of meticulous observation, collective ethical responsibility, and the claims of the world beyond ourselves. (34)

This feature is, however, at least in some way contradictory. Literature and film, as every form of art, are culturally constructed depictions of reality. It is of course true that nature, in the sense the term is used by ecocritics, exists as an entity of its own and beyond ourselves. Nevertheless it cannot find entrance into cultural products in that sense. Even if an author or director would manage to create a perfect depiction of nature it would still be embedded into the cultural construct of his work. And even if that not be so, still, every human being is a captive of his or her own perception. Nature in film is thus twice filtered through the perception of the producer and that of the audience. Pocahontas is a good example for this. Against the background of the fact that it is an animated film and is based on the cultural machinery of the Disney Corporation we realize that the film begins and ends with a copper engraving showing the first and last shot of the film. This refers to the fact that the story of Pocahontas is deeply embedded in American history, culture and self-perception and we realize that nature cannot exist in an authentic way in this film. In the course of the following observations we should always keep in mind that the nature presented in the film is an artificial one. It is always there for a specific purpose and never for its own sake.

2.2 Nature, Culture and Anthropocentrism

Dualism is an “explanation of the world in terms of two opposed terms” (Garrard 183). Ecocriticism tends to divide the world into the terms of nature and culture and to study the relationship between them. In doing so, it regards nature as an entity of its own and in its own right, which eludes cultural beliefs or practice, as Barry points out:

“For the ecocritic, nature really exists, out there beyond ourselves, not needing to be ironised as a concept by enclosure within knowing inverted commas, but actually presents an entity which affects us, and which we can affect, perhaps fatally, if we mistreat it” (252).

One can, of course, argue that the word “nature” (from Latin natura for birth, origin) is a cultural manifestation. It is a term, established by humans, to delimit their world from anything that exists outside this world. On the other hand, one can also argue that humankind as a part of creation is an integral part of nature and that all its cultural expressions are thus, too. The first view, as the ecocritical attempt to regard nature as an entity of its own, tends to see nature as the “other” and excludes humankind from nature in creating a second entity named culture. The second view, on the other hand, rather integrates the concept of culture into the larger concept of nature. As I pointed out earlier, nature cannot find entrance into a cultural construct like a film without being culturally filtered. Every representation of nature in a film serves a certain purpose, even if it is just to entertain the viewer with an epic sight of wilderness. This section of my analysis will regard nature and culture as two separate entities and examine their depiction, their relations and their differences in Disney’s Pocahontas. Furthermore, it will try to investigate and describe how nature in the film is used to move humans into the center of attention and to create anthropocentrism.

In the initial song we find the following lines:

For the New World is like heaven

And we’ll all be rich and free

Or so we have been told

By The Virginia Company. (Pocahontas scene 1)

These lines clearly show that the settlers’ expectations and perception of the New World are totally shaped by a cultural force (The Virginia Company) before they even arrive. Virginia is depicted as an untouched paradise where wealth, freedom and glory are awaiting everyone. The power of culture behind the settlers’ perception is indicated by the line “so we have been told.” Smith is the only one fully breaking through this predetermined view and seeing the New World with other eyes than those of the Virginia Company.

The film continues with a further depiction of culture. Directly after the initial song the Susan Constant is shown in a violent storm. An ecocritical approach moving away from anthropocentrism would regard it just as such, a force of nature regularly appearing in the open sea. But as we are located in the dramatic course of a film we have to analyze the storm in terms of its meaning and anthropocentric potential. Using the ecocritical distinction between nature and culture, the storm may be read as an uproar of the New World’s nature against the cultural forces arriving in form of the settlers. We find proof for this assumption when the power of culture is demonstrated in the same scene. After Smith rescues Thomas’s life, Governor Ratcliffe comes on deck to ask whether there is any trouble. Shortly before he arrives the former storm promptly turns into a mild shower. In this scene Ratcliffe appears as the personification of culture as opposed to nature. His very presence seems to coerce the forces of nature to retreat, thus demonstrating the dominance of culture over nature. Following this course the storm appears as strongly putting humans into the center of attention. This is, of course, not a filmic statement about the dominance of culture over nature. It rather underlines Ratcliffe’s position in this debate and establishes him as the main force of culture in the course of the film.

Scene 3 gives the impression of the complete reverse of a world where nature is subordinated to humans. As Roxana Preda points out:

The Native Americans, on the other hand, are pictured as a communitas, shown to live in balance with nature, living off it without destroying it. The rhythm of their life is attuned to the natural one of the seasons, the cyclical return giving them the stability and security they need. All of nature repeats itself in this eternal rhythm, containing the lives of the tribe in a changeless pattern. In this view, a river is not the symbol of transformation and movement but is “steady like the beating drum.” This steady beat is the ruling metaphor of their existence. Their aim is to “walk in balance,” keep the traditions, take what nature is willing to give. … The Powhatans live in an ecological paradise in which there is no separation between the human and the natural world. This is a clean environment. (325)

The cleanliness and totally harmonic style of the place create the illusion of a world where there is virtually no difference between human and nature. While the settlers are established as the side of culture which exploits nature and is only interested in profit, the Indians are depicted as the side of nature where no such behavior exists. Whether the Powhatans practiced an exploitation of nature or not is an issue of the authentic depiction of Native Americans in film, which I am not able to investigate in this study. The impression that the Indians are totally on a par with nature is, however, only artificially maintained. As the following observations will show, nature, in the case of the Indians, especially Pocahontas, is as much used to put them into the center of attention as in the case of the settlers.

In scene 5 nature seems so be in the focus of attention, but only at first glance. Powhatan wants Pocahontas to accept Kocoum’s hand in marriage and illustrates the situation through nature:

You are the daughter of the chief. It is time to take your place among your people. Even the wild mountain stream must someday join the big river.

As the river cuts his path

Though the river’s proud and strong,

He will choose the smoothest course—

That’s why rivers live so long.

They’re steady

As the steady beating drum. (Pocahontas scene 5)

The analogy between Pocahontas and her people and the big river and the wild mountain stream is obvious. Powhatan’s words correspond to the lifestyle of his people. He compares the path of the daughter of a chief to marry and take her place among her people to a natural process. Social structures are naturalized and disguised as natural and inescapable. The mechanism behind this instrumentalizes nature to put a human in her place. The communitas, in the sense that Preda uses the term, turns out to deprive individuals of their individuality via nature. Pocahontas seems to escape this mechanism in scene 6. But instead of escaping it, she only resumes it. The river becomes a metaphor for the life she is living and the options she is facing. The end of her song illustrates this metaphor in a vivid way:

Should I choose the smoothest course

Steady as the beating drum?

Should I marry Kocoum?

Is all my dreaming at an end?

Or do you still wait for me, dream giver,

Just around the riverbend? (Pocahontas scene 6)

In Scene 7 the juxtaposition of nature and culture reaches a first climax. Pocahontas, not able to interpret her dream and to find her path, asks Grandmother Willow for advice.

[Pocahontas] But, Grandmother Willow, what is my path? How am I ever going to find it?

[Grandmother Willow] Your mother asked me the very same question.

[P] She did? What did you tell her?

[GW] I told her to listen. All around you are spirits, child. They live in the earth, the water, the sky. If you listen, they will guide you. (Pocahontas scene 7)

Grandmother Willow brings Pocahontas’s attention to the spirits living invisibly in the visible nature. The powers of nature, concreted in the concept of these spirits, have the power to guide if one listens. Grandmother Willow invokes this power with her song. “Que que na-tor-ra” is Algonquin and means “you will understand.” It is remarkable, though a coincidence, that the word na-to-ra, meaning “to understand,” resembles the word natura, or nature, thus indicating that nature and to understand mean the very same thing. However, for Pocahontas this is true. As she begins to listen to nature she understands. As Grandmother Willow begins to sing, disembodied voices can be heard and a mystical breeze moves her branches. The same voices repeat the last line of her song. It is likely to regard them as the voices of the spiritual world making themselves audible for Pocahontas to allow her to connect with it.

The connection succeeds. When Pocahontas listens to the wind it tells her that “strange clouds” are coming. As she climbs on a tree and glances over the landscape she notices the sails of the Susan Constant seeming to glide slowly over the treetops. In her answer to Grandmother Willow’s question what she is seeing she agrees with the wind: “Clouds. Strange clouds.” Ecocritics see nature as an entity of its own and in its own right existing beyond human terms of reality. What the wind is telling Pocahontas and what she sees prove this claim in a vivid way. The nature of the New World, impersonated in the wind, is totally unaware of white European culture. Literally “seeing” the sails of the Susan Constant for the first time it does the only logical thing in settling them with its own picture area and finding a matching concept. The sails are clouds, strange clouds, though. The very same mechanism, though used by a human, is at work a few minutes earlier when Pocahontas tells Grandmother Willow about her dream. She translates the compass she is dreaming about into a spinning arrow matching her own reality.

In scene 12 we find a similar case as in scene 2. Smith, who is scouting the terrain, perceives the presence of a stranger and hides behind a waterfall, ready to shoot. As he notices Pocahontas’s shape through the water he jumps out and points his gun at her. The situation is then strongly dramatized. Pocahontas’s body appears from out of the mist. The wind softly plays in her hair. She looks at Smith with a mixture of innocence and vulnerability. He looks deep into her eyes and wades through the water to reach her—and then she runs off. Two details are easily overlooked in this scene. First, the mist virtually appears within a second, and second, the sound of the waterfall suddenly stops. These seemingly circumstantial details appear in a very interesting light from an ecocritical perspective. The mist only serves to provide the moment with more pathos. The waterfall appears analogously to the storm in scene 2. Natural phenomena are simply subordinated in human presence or seem to appear and disappear in order to accentuate a situation where humans are in the center of attention. The mist and the waterfall are not independent natural phenomena in this scene. They are mere effects, switched on or off in the right moment to contribute to anthropocentrism.

We have investigated the dualism between nature and culture so far. Some ecocritics seek to achieve a status for nature in which it incorporates culture. In Disney’s Pocahontas, however, it shows that nature is subordinated to culture. Powerful forces of nature seem to retreat in humans’ presence. Natural phenomena are switched on or off at the right time as if they were special effects. Nature represents human struggles and situations. It also came to light that Powhatan disguises the way of life of his people as a natural process. But it was also shown that nature can make itself audible and form itself a platform. We found out that nature has its own picture area to which cultural phenomena may be applied.

2.3 The Leaves as Recurring Element

During the whole film a gust of wind carrying a handful of multicolored leaves accompanies nearly every movement the heroine is making. The leaves appear more often in the film than any other element of nature, and thus need special attention. They are closely connected with the role of wind in the film. Their first appearance, at the transition of scenes 2 and 3, indicates this. Kekata explains Pocahontas’s absence to Powhatan with the words: “She has her mother’s spirit. She goes wherever the wind takes her.” We then see a stream of leaves appearing and guiding us to Pocahontas, who stand on a cliff. In scene 7 Grandmother Willow tells Pocahontas to listen to the wind. As Pocahontas begins to open up her mind for the voices of the spiritual world the leaves appear. In scene 17 Powhatan claims to feel her mother’s presence in the wind:

[C] When I see you wear that necklace, you look just like your mother.

[Pocahontas] I miss her.

[CP] But she is still with us. Whenever the wind moves through the trees, I feel her presence. Our people look to her for wisdom and strength. Someday, they will look to you as well.

[P] I would be honoured by that.

The wind is established as the main force of nature in the film. It contrasts with Ratcliffe, who has previously been established as the main force of culture in the film. The leaves are a visualization of the wind. That way, it is easier for the viewer to recognize the wind’s role and functions in the film.

The leaves serve three main functions. First, they are the link between humans and nature. As Preda points out: “In the scene of the rescue it is only after feeling the wind that Powhatan consents to let Smith live” (334). The same thing happens to Smith, who is not a full part of Pocahontas’s reality in scene 15 before he has been caressed by the wind on a cliff. Pocahontas appears in a similar situation in scene 4. The wind seems to have the power to open one’s eyes to the beauty of the natural world, as in Smith’s case, and to make one feel its serenity and clarity, as in Powhatan’s case. Second, the leaves have a general connecting function in terms of love and language. In scene 12 Pocahontas and Smith’s hands reaching for each other are surrounded by a knot of leaves. It seems as if the wind expresses the validity of the connection. It also seems to initiate the sudden and inexplicable codeswitching of Pocahontas and all the other characters. In the next shot we see Pocahontas and Smith standing face to face surrounded by a helix of leaves. As the leaves appear from Pocahontas’s side and only in her presence and connect Smith to her a view seeing culture as an integral part of nature is supported. The last scene of the film gives a very strong impression of this connecting power. As Pocahontas is standing on a cliff looking at the Susan Constant in the distance, a powerful stream of leaves appears from behind her; it unerringly bears down on the ship and reaches Smith. It creates a last and powerful link between the settlers and the Indians, between Smith and Pocahontas, between nature and culture and between two worlds. It points to a final synthesis in the dualism between nature and culture. Third, the leaves accompany the movements of the heroine and underline her spirituality and permanent connection with the natural world. They lead us to her in scene 4. They appear and follow her in scene 15. They symbolize the transport of her feelings to Smith in the last scene. But the most important point is that they indicate the connection with nature beginning in scene 8 and the renaissance of this connection in scene 24 when Pocahontas eventually recognizes the meaning of the compass and her path.

The wind and the leaves it carries are the most frequent and striking appearance of nature in the film. They are conspicuous and their function is always clear to the viewer. Moreover, they fulfill most of the functions of nature in the film. However, they always serve to illustrate human issues. Whether they guide our gaze, build up a connection with nature, or underline a relationship, the link with humans is always given. The leaves are the force of nature with the strongest anthropocentric potential in the film.

2.4 Animals

The following section will investigate the trope of animals as introduced by Garrard in his book on ecocriticism (136–59). Some of the ideas Garrard discusses in his chapter on animals, especially the idea of anthropomorphism, shall be applied to the representation of animals in Pocahontas. The most noticeable representatives of animals in the film are Meeko the raccoon and Flit the hummingbird, who accompany Pocahontas. The principle of anthropomorphism can be demonstrated in a vivid way using these two characters. Anthropomorphism means “that we mistakenly ascribe human attributes … to the animals involved” (Garrard 137). With regard to Meeko and Flit this process already began in their creation. Nik Ranieri, the supervising animator for Meeko, drew his inspiration in creating the raccoon from himself. He used his acting talent to make Meeko come to life. This requires, of course, that Meeko’s character and movements are basically human. Dave Pruiksma, the supervising animator for Flit, studied hummingbirds to come up with all the right moves and create Flit’s character. This seems a good starting point to examine how anthropomorphism shows in these animals. To begin with, Meeko and Flit seem to relate to each other through a kind of friendship in which they tease each other constantly. Meeko is more of the funny and clumsy type, open to everyone and every new situation and always in search of food. Flit is shown as wary, careful, and as Pocahontas points out, “very stubborn.” In many situations the two of them behave like their human models and show human attributes as certain feelings, character traits, and behavior. Moreover, they are in possession of fully developed facial expressions and can show joy, uncertainty, and even sullenness.