This is “Ecocriticism: An Overview”, section 8.2 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.2 Ecocriticism: An Overview

Literary critics have long been interested in the way the natural world influences literary expression. For instance, in his important 1964 book The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, Leo Marx demonstrated that a “pastoral ideal” guided the formation of American culture, identity, and literature. This “urge to idealize a simple, rural environment,” Marx argues, continued even as America became “an intricately organized, urban, industrial, nuclear-armed society.”Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). Marx sees much of American literature as a response to this tension between urban realities (“the machine”) and pastoral ideals (“the garden”). Many other literary critics who wrote before the advent of a formal ecocritical school investigated similar topics, particularly when they studied authors who write frequently about nature, such as the Romantics of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The term RomanticismA movement of artists, writers, and philosophers during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Continental Europe, England, and the United States. Romantic thinkers and writers idealized emotional experiences and the natural world, eschewing many of the scientific, industrial, and capitalistic ideals that had come to define their societies. doesn’t have anything to do with steamy love scenes. Instead, Romanticism was an intellectual movement that idealized emotional experiences and the natural world, eschewing many of the scientific, industrial, and capitalistic ideals that had come to define society between, roughly, 1800–50. The following oil painting, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), by the German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich demonstrates the Romantic position. The painting can be interpreted in a variety of ways. An ecocritical reading might examine humanity’s relationship to nature—a human’s desire to appreciate the sheer power of the natural world—yet there seems to be a suggestion that the man, with his walking stick, is also contemplating the way to harness this power of nature, to civilize the natural world.

Painting by Caspar David Friedrich, The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818).

To get a better sense of these concerns, let’s look at “The World Is Too Much with Us,” a poem written by one of the most well-known Romantics, William Wordsworth.William Wordsworth, “The World Is Too Much with Us,” Poets.org, http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15878. It was published in 1807.

“The World Is Too Much with Us” by William Wordsworth

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers,

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.—Great God! I’d rather be

A pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

Your Process

- What do you think Wordsworth means by “the world” in this poem? How is “the world” distinct from “Nature”? Why do you think Wordsworth splits these two ideas apart? Record your thoughts.

- A related question: Why do you think Wordsworth capitalizes “Nature” and “Sea” in the poem? What other words are capitalized, and how might they relate to these two words? Jot down your ideas.

For a critic interested in literature and nature, Wordsworth’s poems are rich territory. In “The World Is Too Much with Us,” the speaker worries that people “lay waste” their “powers” because they are too wrapped up with “getting and spending.” In other words, the concerns of industry and commerce have crowded out those things that the speaker believes give human beings their power. We can read “the world” in the poem as the constructed world of human cities and concerns; that world “is too much with us” while the natural world has become estranged from humanity. “Little we see in Nature that is ours,” the speaker worries, and “we are out of tune” with “this Sea,” “the moon,” and “the winds.” By claiming that human beings have fallen out of tune with nature, the speaker implies that humanity was once in tune with it. The poem mourns a profound loss for men and women, who can no longer feel the emotions that bucolic natural scenes should evoke in them: “It moves us not.”

In the final lines of “The World Is Too Much with Us,” Wordsworth’s speaker wishes he could trade his modern existence for a more primitive life that is closer to nature. “Great God!” he exclaims, “I’d rather be / a pagan suckled in a creed outworn.” In other words, while the speaker does not believe in, say, the Greek myths—he insists that such religions are “outworn”—he would nonetheless trade his more modern ideas for a faith that allowed him to see the divine in the natural world. Keep in mind the Greek myths, in which each aspect of the natural world is overseen by a god or goddess, and in which many plants, animals, and natural features are said to embody mythical heroes or monsters. Wordsworth’s speaker wishes he could, when looking at the ocean, see more than water. He wishes he could see also “Proteus rising from the sea” and “hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.” Were he able to recognize the divinity of nature, the speaker insists, he would be “less forlorn” about his life in the modern world.

Whether they wrote during the Romantic period or not, writers who focus explicitly on nature in their works (e.g., John Keats, Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, and Annie Dillard) lend themselves well to this kind of analysis. However, modern ecocritics have expanded their focus to include much writing that’s not explicitly about nature. Ecocritics are interested in the attitudes that literary works express about nature, whether those attitudes are expressed consciously through the themes or plot of a work or unconsciously through the work’s symbols or language (for a thorough explanation of the unconscious, see Chapter 3 "Writing about Character and Motivation: Psychoanalytic Literary Criticism"). Even a work set in a city—the most urban of spaces—can nonetheless convey ideas about the loss of nature. Ecocritics can discuss the absence of nature in a work as well as its presence.

One could argue that a key turning point was the Industrial Revolution, which transformed the way people lived in worked in the nineteenth century. Moving from an agrarian or agricultural model to one centered on industry, the Industrial Revolution further reinforced the divide between the city and the country. Here are a few opening paragraphs from Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1852–53):

London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little 'prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon and hanging in the misty clouds.

Gas looming through the fog in divers places in the streets, much as the sun may, from the spongey fields, be seen to loom by husbandman and ploughboy. Most of the shops lighted two hours before their time—as the gas seems to know, for it has a haggard and unwilling look.

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation, Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

Never can there come fog too thick, never can there come mud and mire too deep, to assort with the groping and floundering condition which this High Court of Chancery, most pestilent of hoary sinners, holds this day in the sight of heaven and earth.

Dickens’s famous first sentence—“London.”—sets the action in London, where the mud and fog overpower the city. Dickens uses the “filth” of London as a symbol for the corruption of Chancery, the court system of London, but he’s also depicting a London that is diseased by industrialization—the fog, in particular, reflects the poor air quality of London during this time as coal-powered factories spewed their smoke over the city.

In America, writers also focused on the environment and the dangers of industrialization. Two famous examples are Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854), which you can read at http://thoreau.eserver.org/walden00.html, and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Nature” (1836), which you can read at http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl302/texts/emerson/nature-emerson-a.html #Introduction. Thoreau and Emerson, in fact, are two of the earliest ecocritical voices in America, and their influence was significant. Emerson and Thoreau argued that experiences in nature were the most authentic in human existence, and they urged their countrymen and women to go into the natural world for inspiration. Those ideas continue to inform literature to this day but also more tangible aspects of our lives, such as the dedication of so many communities to creating green spaces—parks, greenways, or river walks—for their citizens. Let’s look at a classic example, Rebecca Harding Davis’s 1861 short story, Life in the Iron Mills.

Your Process

- As we’ve suggested throughout this text, these process papers will make more sense if you are familiar with the literary work under discussion. For this section, you should read Rebecca Harding Davis’s short story, Life in the Iron Mills, which you can find in full as an e-text provided by Project Gutenberg (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm) and as a free audiobook provided by Librivox (http://librivox.org/life-in-the-iron-mills-by-rebecca-harding-davis/).

- As you read the story, keep a running list of all the references you find to the natural world. You can list natural features described, discussions of the characters’ attitudes toward nature, or anything else that seems to comment on humanity’s relationship to its environment.

- You might also be interested to look at the magazine in which Life in the Iron Mills originally appeared: The Atlantic for April 1861. You can find this historical text for free at the Internet Archive (http://archive.org/details/atlantic07bostuoft). Harding Davis’s story appears on page 430. Look at the articles that appear around this short story—how might those contexts help you build a “thick description” of Harding Davis’s text? For more on “thick description,” see Chapter 7 "Writing about History and Culture from a New Historical Perspective".

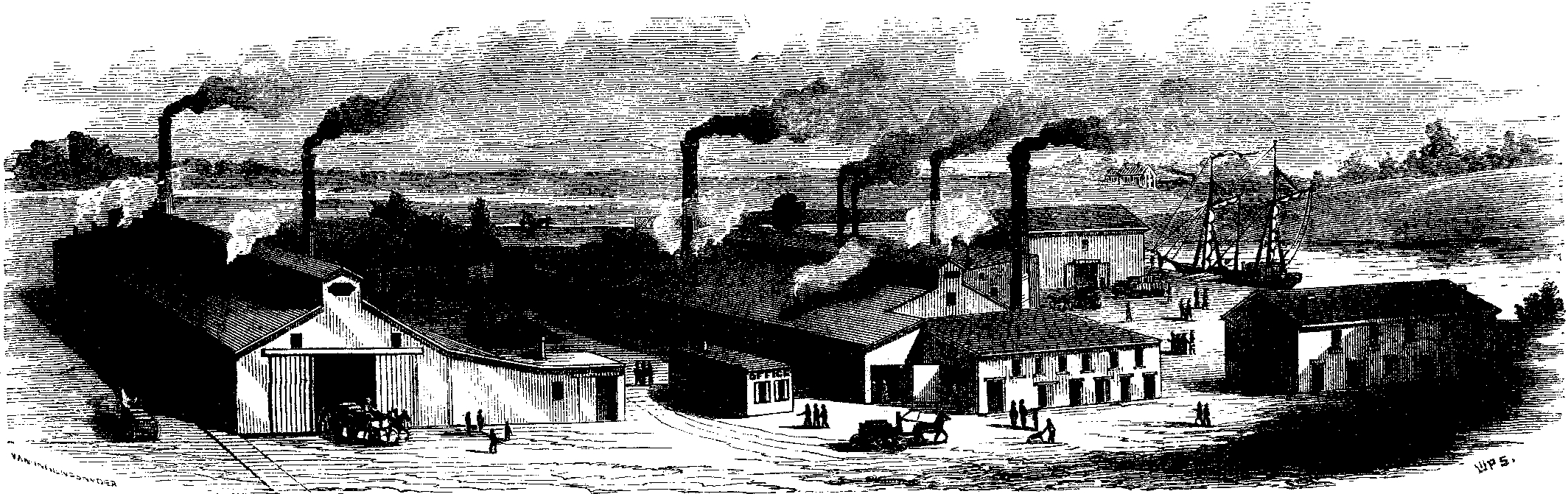

Illustration from “Wilmington and Its Industries,” Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science (April, 1873).

Life in the Iron Mills recounts a story of Welsh immigrants working in an iron-mill town along the Ohio River in an area that would become West Virginia. Readings of this story often focus on its critique of industrialization and capitalism. For instance, a critic might look at the ways that Hugh Wolfe’s artistic talents cannot flower in the story because of his class or ethnic background (see Chapter 5 "Writing about Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Identity" for ideas about how you might develop such a reading). Let’s look closely at the story’s opening paragraphs, however, with an eye to the text’s attitudes toward the environment and natural world.

A cloudy day: do you know what that is in a town of iron-works? The sky sank down before dawn, muddy, flat, immovable. The air is thick, clammy with the breath of crowded human beings. It stifles me. I open the window, and, looking out, can scarcely see through the rain the grocer’s shop opposite, where a crowd of drunken Irishmen are puffing Lynchburg tobacco in their pipes. I can detect the scent through all the foul smells ranging loose in the air.

The idiosyncrasy of this town is smoke. It rolls sullenly in slow folds from the great chimneys of the iron-foundries, and settles down in black, slimy pools on the muddy streets. Smoke on the wharves, smoke on the dingy boats, on the yellow river,—clinging in a coating of greasy soot to the house-front, the two faded poplars, the faces of the passers-by. The long train of mules, dragging masses of pig-iron through the narrow street, have a foul vapor hanging to their reeking sides. Here, inside, is a little broken figure of an angel pointing upward from the mantel-shelf; but even its wings are covered with smoke, clotted and black. Smoke everywhere! A dirty canary chirps desolately in a cage beside me. Its dream of green fields and sunshine is a very old dream,—almost worn out, I think.

From the back-window I can see a narrow brick-yard sloping down to the river-side, strewed with rain-butts and tubs. The river, dull and tawny-colored, (la belle riviere!) drags itself sluggishly along, tired of the heavy weight of boats and coal-barges. What wonder? When I was a child, I used to fancy a look of weary, dumb appeal upon the face of the negro-like river slavishly bearing its burden day after day. Something of the same idle notion comes to me to-day, when from the street-window I look on the slow stream of human life creeping past, night and morning, to the great mills. Masses of men, with dull, besotted faces bent to the ground, sharpened here and there by pain or cunning; skin and muscle and flesh begrimed with smoke and ashes; stooping all night over boiling caldrons of metal, laired by day in dens of drunkenness and infamy; breathing from infancy to death an air saturated with fog and grease and soot, vileness for soul and body. What do you make of a case like that, amateur psychologist? You call it an altogether serious thing to be alive: to these men it is a drunken jest, a joke,—horrible to angels perhaps, to them commonplace enough. My fancy about the river was an idle one: it is no type of such a life. What if it be stagnant and slimy here? It knows that beyond there waits for it odorous sunlight, quaint old gardens, dusky with soft, green foliage of apple-trees, and flushing crimson with roses,—air, and fields, and mountains. The future of the Welsh puddler passing just now is not so pleasant. To be stowed away, after his grimy work is done, in a hole in the muddy graveyard, and after that, not air, nor green fields, nor curious roses.

Can you see how foggy the day is? As I stand here, idly tapping the windowpane, and looking out through the rain at the dirty back-yard and the coalboats below, fragments of an old story float up before me,—a story of this house into which I happened to come to-day. You may think it a tiresome story enough, as foggy as the day, sharpened by no sudden flashes of pain or pleasure.—I know: only the outline of a dull life, that long since, with thousands of dull lives like its own, was vainly lived and lost: thousands of them, massed, vile, slimy lives, like those of the torpid lizards in yonder stagnant water-butt.—Lost? There is a curious point for you to settle, my friend, who study psychology in a lazy, dilettante way. Stop a moment. I am going to be honest. This is what I want you to do. I want you to hide your disgust, take no heed to your clean clothes, and come right down with me,—here, into the thickest of the fog and mud and foul effluvia. I want you to hear this story. There is a secret down here, in this nightmare fog, that has lain dumb for centuries: I want to make it a real thing to you. You, Egoist, or Pantheist, or Arminian, busy in making straight paths for your feet on the hills, do not see it clearly,—this terrible question which men here have gone mad and died trying to answer. I dare not put this secret into words. I told you it was dumb. These men, going by with drunken faces and brains full of unawakened power, do not ask it of Society or of God. Their lives ask it; their deaths ask it. There is no reply. I will tell you plainly that I have a great hope; and I bring it to you to be tested. It is this: that this terrible dumb question is its own reply; that it is not the sentence of death we think it, but, from the very extremity of its darkness, the most solemn prophecy which the world has known of the Hope to come. I dare make my meaning no clearer, but will only tell my story. It will, perhaps, seem to you as foul and dark as this thick vapor about us, and as pregnant with death; but if your eyes are free as mine are to look deeper, no perfume-tinted dawn will be so fair with promise of the day that shall surely come.Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills (1861; Project Gutenberg 2008), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm.

These first paragraphs detail the scenery of the narrator’s world (and notice the similarity to Dickens). In this case, however, the scenery described is obscured by the products of human industry. The natural world is obscured both figuratively (“The air is thick, clammy with the breath of crowded human beings.”) and literally, by smoke: “The idiosyncrasy of this town is smoke. It rolls sullenly in slow folds from the great chimneys of the iron-foundries, and settles down in black, slimy pools on the muddy streets. Smoke on the wharves, smoke on the dingy boats, on the yellow river,—clinging in a coating of greasy soot to the house-front, the two faded poplars, the faces of the passers-by.” The river, too, is polluted; it’s “dull and tawny-colored” and “tired” of the many “boats and coal-barges” bringing goods to and from the town. The town is so polluted that its human inhabitants suffer acutely, “breathing from infancy to death an air saturated with fog and grease and soot, vileness for soul and body.”

The ecocritic might interpret this story as a sustained critique of a modern society that disregards the needs of the planet in order to advance the narrow priorities of industrial and consumer culture. In order to produce iron, the material that shaped so much of the Industrial Revolution, the owners of the factories in this story have destroyed the air, the water, and even the health of the human beings who make their business run. In fact, they have made all of nature (including human beings) slaves to industry. The river is imagined as “slavishly bearing its burden day after day.” The men who work in the factories are so broken in spirit that they consider their lives “a drunken jest, a joke.” The narrator points out that far beyond this town one can find “odorous sunlight, quaint old gardens, dusky with soft, green foliage of apple-trees, and flushing crimson with roses,—air, and fields, and mountains.” These healthful natural features, however, are beyond the reach and understanding of those living in this “town of iron-works,” who are “stowed away, after [their] grimy work is done, in a hole in the muddy graveyard, and after that, not air, nor green fields, nor curious roses.” Harding Davis’s novella, then, draws an explicit parallel between human flourishing and human treatment of the natural world. When human beings disregard nature, Life in the Iron Mills implies, they suffer with nature.

What’s more, the narrator of Harding Davis’s story challenges the story’s readers to come to terms with the realities described in the novella. The original readers of this story would have been subscribers to the Atlantic magazine, which means they would likely have been educated, financially secure members of middle- or upper-class society. In other words, they would have been nothing like the iron workers Harding Davis writes of in the story and would not have experienced the absolute deprivation from nature the tale relates. Her narrator addresses this discrepancy directly:

There is a curious point for you to settle, my friend, who study psychology in a lazy, dilettante way. Stop a moment. I am going to be honest. This is what I want you to do. I want you to hide your disgust, take no heed to your clean clothes, and come right down with me,—here, into the thickest of the fog and mud and foul effluvia. I want you to hear this story. There is a secret down here, in this nightmare fog, that has lain dumb for centuries: I want to make it a real thing to you. You, Egoist, or Pantheist, or Arminian, busy in making straight paths for your feet on the hills, do not see it clearly,—this terrible question which men here have gone mad and died trying to answer. I dare not put this secret into words.Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills (1861; Project Gutenberg 2008), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm.

There’s a lot going on in these few sentences, but the ecocritic would likely concentrate on the way Harding Davis’s narrator insists that her readers must experience the horrible environmental conditions of her subjects in order to understand their story. Her readers must “take not heed to [their] clean clothes” and “come right down…into the thickest of the fog and mud and foul effluvia.” Readers “busy in making straight paths for [their] feet on the hills” cannot “see clearly” the plight of those who cannot spend time in the hills, experiencing the natural world without smoke and mud and effluvia.

These natural themes continue throughout Life in the Iron Mills. At the end of the novella, in fact, Deborah—one of the characters deformed, body and soul, by her time in the mill town—is taken in by Quakers who live in the hills near the town.If you’re unfamiliar with the Quakers, or the Religious Society of Friends, see this resource from the BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/subdivisions/quakers_1.shtml. The narrator reports that life in closer communion with nature purifies Deborah:

There is no need to tire you with the long years of sunshine, and fresh air, and slow, patient Christ-love, needed to make healthy and hopeful this impure body and soul. There is a homely pine house, on one of these hills, whose windows overlook broad, wooded slopes and clover-crimsoned meadows,—niched into the very place where the light is warmest, the air freest. It is the Friends’ meeting-house. Once a week they sit there, in their grave, earnest way, waiting for the Spirit of Love to speak, opening their simple hearts to receive His words. There is a woman, old, deformed, who takes a humble place among them: waiting like them: in her gray dress, her worn face, pure and meek, turned now and then to the sky.Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills (1861; Project Gutenberg 2008), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/876/876-h/876-h.htm.

Living in greater harmony with nature “make[s] healthy and hopeful” Deborah’s “impure body and soul.” The warm light, free air, “wooded slopes,” and “clover-crimsoned meadows” all contribute to her restoration. In the last view readers have of Deborah, she turns her face “now and then to the sky.”

Harding Davis’s Life in the Iron Mills can be read, then, as a searching critique of modern society without nature—a warning about what mass industrialization will do to the environment and the men and women who rely on it. You can probably see that these ideas relate closely to ideas one would find in modern environmentalistA modern philosophy and social movement dedicated to improving human beings’ interactions with the natural world, often through practices designed to mitigate damage that human beings have done to it in the past. Environmentalists advocate for restoration of natural spaces, conservation of natural resources, and control of practices that damage the natural world. thought. We can read Harding Davis’s story as an exposé of human practices that permanently scar the natural world—an argument against pollution and waste. In cases like this, we want to be careful of anachronismSomething placed in an incorrect time period. In literature, anachronism often refers to objects, ideas, phrases, or the like placed in historically inappropriate scenes. For instance, if a character in a story set during the Civil War (1861–1865) was described driving a car, we would call the car anachronistic.. Harding Davis wrote this work long before scientists and other thinkers articulated the ideas and principles of the modern environmentalist movement. We wouldn’t, for instance, want to discuss Life in the Iron Mills as advocating for recycling, a word and practice of which Harding Davis would never have heard. Nevertheless, we can point out sympathetic ideas between Harding Davis’s story and modern environmentalist concerns, drawing out nuances of the story that may not have been apparent to earlier readers.

Your Process

- After looking at these two examples, what seem to be the primary questions that ecocritics ask of literary works? In the notes box, make a list of priorities (i.e., things to look out for) for you to follow when you read as an ecocritic.

When you’re reading literature as an ecocritic, then, start by asking the following questions:

- How does this novel, story, poem, play, or essay represent the natural world (e.g., plants, animals, ecosystems)? Is nature portrayed positively, negatively, or otherwise?

- How does the work represent the relationship between human beings and nature? For instance, is the relationship symbiotic or adversarial?

- Do the characters in the work express ideas or opinions about their environment (whether a “natural” environment as in Wordsworth’s poem or a man-made environment as in Harding Davis’s story)? What cultural, social, or political values do characters seem to embody? When asking this question, don’t forget to consider the narrator!

- Does the text engage consciously with ideas related to modern environmentalism? For instance, does the text seem to make an argument for or against conservationism, preservation, or restoration?