This is “Literary Snapshot: Through the Looking-Glass”, section 8.1 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.1 Literary Snapshot: Through the Looking-Glass

Lewis Carroll, as we found out in previous chapters, is most famous for two books: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1872). These books follow the adventures of a seven-year-old, Alice, who tumbles down a rabbit hole (Wonderland) and enters a magic mirror (Looking-Glass), entering a nonsensical world of the imagination. If you have not already read these classic books—or wish to reread them—you can access them at the following links:

http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html

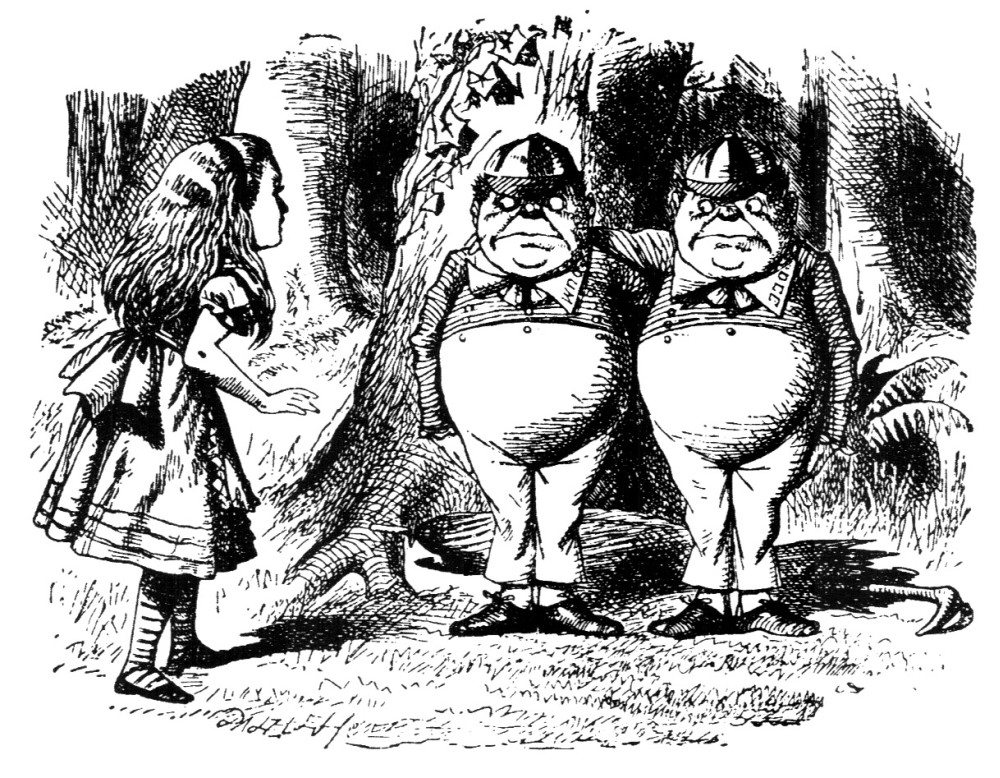

In Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice meets the twins Tweedledum and Tweedledee, who recite the following poem. It’s a long poem (as Alice worries it will be), but the episode is worth reading in full:

“What shall I repeat to her?” said Tweedledee, looking round at Tweedledum with great solemn eyes, and not noticing Alice’s question.

“‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ is the longest,” Tweedledum replied, giving his brother an affectionate hug.

Tweedledee began instantly:

“The sun was shining—”

Here Alice ventured to interrupt him. “If it’s very long,” she said, as politely as she could, “would you please tell me first which road—”

Tweedledee smiled gently, and began again:

“The sun was shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might:

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright—

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.

The moon was shining sulkily,

Because she thought the sun

Had got no business to be there

After the day was done—

‘It’s very rude of him,’ she said,

‘To come and spoil the fun!’

The sea was wet as wet could be,

The sands were dry as dry.

You could not see a cloud, because

No cloud was in the sky:

No birds were flying overhead—

There were no birds to fly.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

‘If this were only cleared away,’

They said, ‘it would be grand!’

‘If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year,

Do you suppose,’ the Walrus said,

‘That they could get it clear?’

‘I doubt it,’ said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear.

‘O Oysters, come and walk with us!’

The Walrus did beseech.

‘A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach:

We cannot do with more than four,

To give a hand to each.’

The eldest Oyster looked at him.

But never a word he said:

The eldest Oyster winked his eye,

And shook his heavy head—

Meaning to say he did not choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But four young Oysters hurried up,

All eager for the treat:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat—

And this was odd, because, you know,

They hadn’t any feet.

Four other Oysters followed them,

And yet another four;

And thick and fast they came at last,

And more, and more, and more—

All hopping through the frothy waves,

And scrambling to the shore.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Walked on a mile or so,

And then they rested on a rock

Conveniently low:

And all the little Oysters stood

And waited in a row.

‘The time has come,’ the Walrus said,

‘To talk of many things:

Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax—

Of cabbages—and kings—

And why the sea is boiling hot—

And whether pigs have wings.’

‘But wait a bit,’ the Oysters cried,

‘Before we have our chat;

For some of us are out of breath,

And all of us are fat!’

‘No hurry!’ said the Carpenter.

They thanked him much for that.

‘A loaf of bread,’ the Walrus said,

‘Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed—

Now if you’re ready Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed.’

‘But not on us!’ the Oysters cried,

Turning a little blue,

‘After such kindness, that would be

A dismal thing to do!’

‘The night is fine,’ the Walrus said

‘Do you admire the view?

‘It was so kind of you to come!

And you are very nice!’

The Carpenter said nothing but

‘Cut us another slice:

I wish you were not quite so deaf—

I’ve had to ask you twice!’

‘It seems a shame,’ the Walrus said,

‘To play them such a trick,

After we’ve brought them out so far,

And made them trot so quick!’

The Carpenter said nothing but

‘The butter’s spread too thick!’

‘I weep for you,’ the Walrus said.

‘I deeply sympathize.’

With sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of the largest size.

Holding his pocket handkerchief

Before his streaming eyes.

‘O Oysters,’ said the Carpenter.

‘You’ve had a pleasant run!

Shall we be trotting home again?’

But answer came there none—

And that was scarcely odd, because

They’d eaten every one.”

“I like the Walrus best,” said Alice: “because you see he was a little sorry for the poor oysters.”

“He ate more than the Carpenter, though,” said Tweedledee. “You see he held his handkerchief in front, so that the Carpenter couldn’t count how many he took: contrariwise.”

“That was mean!” Alice said indignantly. “Then I like the Carpenter best—if he didn’t eat so many as the Walrus.”

“But he ate as many as he could get,” said Tweedledum.

This was a puzzler. After a pause, Alice began, “Well! They were both very unpleasant characters—”Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (New York: Macmillan, 1899; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1993), chap. 4, http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html.

We might interpret the poem didactically: as a warning to children not to trust strange adults, for instance. The “eldest Oyster” refuses to follow the Walrus and the Carpenter, and he, unlike his siblings, isn’t eaten. Indeed, the poem was probably meant to mimic or even parody didactic children’s literature from the nineteenth century. It’s recited by Tweedledum and Tweedledee, after all, who “looked so exactly like a couple of great schoolboys” and who recite poems with great vigor, as if eager to please a teacher.

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Through the LookingGlass and What Alice Found There (1872).

There’s another possibility here, however. We can read this episode as a commentary on human beings’ relationships with the natural world. Look at the way the Walrus and Carpenter discuss the beach they’re walking on: “They wept like anything to see / Such quantities of sand: / ‘If this were only cleared away,’ / They said, ‘it would be grand!’” They wish to clear away the sand—to alter the landscape to suit their whims. That landscape is already altered: “You could not see a cloud,” the poem relates, “because / No cloud was in the sky.” What’s more, “No birds were flying overhead— / There were no birds to fly.” The natural world is marked by absence in this poem, and its two central characters weep because they cannot remove the sand from the seashore. Reading through the lens of environmental or ecocriticismA school of literary criticism that studies the depiction of the physical environment in works of literature. Ecocriticism often focuses on the way literary works depict human attitudes toward and interactions with the natural world., we might interpret these characters as representatives of human disregard for nature.

Such a reading might also help us understand the Walrus’s and the Carpenter’s treatment of the Oysters. They don’t simply trick the Oysters for sustenance—they gorge themselves, eating every one. They need “another slice” of bread, thickly spread butter, and “pepper and vinegar besides.”

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Through the LookingGlass and What Alice Found There (1872).

Look at the illustration of this scene: you see the Carpenter looking a little sick from overeating, and oyster shells strewn all around the beach like litter. It’s a scene of excess, of ill restraint. After hearing this story, Alice can’t decide which character was most unpleasant—the Walrus, who consumed the most oysters, or the Carpenter, who seemed unrepentant for his deceit. Alice, then, sees two moral problems in what the Walrus and the Carpenter do in the poem. First, she rejects their lack of sympathy for the Oysters, and second, she rejects the wastefulness of their consumption. In the end, Alice simply decides, “Well! They were both very unpleasant characters.” Part of what makes them so unpleasant, an ecocritic might suggest, is that they view the natural world and its creatures as theirs to exploit, with no repercussions or responsibilities on their part.