This is “New Historical Criticism: An Overview”, section 7.2 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.2 New Historical Criticism: An Overview

Early scholars of literature thought of history as a progression: events and ideas built on each other in a linear and causal way. History, consequently, could be understood objectively, as a series of dates, people, facts, and events. Once known, history became a static entity. We can see this in the previous example from Wonderland. The Mouse notes that the “driest thing” he knows is that “William the Conqueror, whose cause was favoured by the pope, was soon submitted to by the English, who wanted leaders, and had been of late much accustomed to usurpation and conquest. Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria—” I think we would all agree to moan “Ugh!” In other words, the Mouse sees history as a list of great dead people that must be remembered and recited, a list that refers only to the so-called great events of history: battles, rebellions, and the rise and fall of leaders. Corresponding to this view, literature was thought to directly or indirectly mirror historical reality. Scholars believed that history shaped literature, but literature didn’t shape history.

While this view of history as a static amalgamation of facts is still considered important, other scholars in the movement called New HistoricismNew Historicism situates literary texts in their historical contexts, reading literary works as dynamic interplays of cultural, economic, artistic, religious, political, and social forces. see the relationship between history and literature quite differently. Today, most literary scholars think of history as a dynamic interplay of cultural, economic, artistic, religious, political, and social forces. They don’t necessarily concentrate solely on kings and nobles, or battles and coronations. In addition, they also focus on the smaller details of history, including the plight of the common person, popular songs and art, periodicals and advertisements—and, of course, literature. New Historical scholarship, it follows, is interdisciplinaryInterdisciplinary scholarship draws on insights from a range of academic fields., drawing on materials from a number of academic fields that were once thought to be separate or distinct from one another: history, religious studies, political science, sociology, psychology, philosophy, and even the natural sciences. In fact, New Historicism is also called cultural materialismCultural materialism views all texts—for example, literature, religious tracts, political polemics, or scientific discoveries—as artifacts of history that reflect larger cultural issues. since a text—whether it’s a piece of literature, a religious tract, a political polemic, or a scientific discovery—is seen as an artifact of history, a material entity that reflects larger cultural issues.

Your Process

- How have you learned to connect literature and history? Jot down two or three examples from previous classes.

Sometimes it’s obvious the way history can help us understand a piece of literature. When reading William Butler Yeats’s poem “Easter 1916” (which you can read online at http://www.poetryfoundation .org/poem/172061), for instance, readers immediately wonder how the date named in the poem’s title shapes the poem’s meaning.“Easter 1916 by William Butler Yeats,” The Atlantic Online, http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/poetry/soundings/easter.htm. Curious readers might quickly look up that Easter date and discover that leaders of the Irish independence movement staged a short-lived revolt against British rule during Easter week in 1916. The rebellion was quickly ended by British forces, and the rebel leaders were tried and executed. Those curious readers might then understand the allusions that Yeats makes to each of the executed Irish leaders in his poem and gain a better sense of what Yeats hopes to convey about Ireland’s past and future through his poem’s symbols and language. Many writers, like Yeats, use their art to directly address social, political, military, or economic debates in their cultures. These writers enter into the social discourseThe way that language represents or reinforces the ways of knowing and thinking in a society, community, or group. of their time, this discourse being formed by the cultural conditions that define the age. Furthermore, this discourse reflects the ideologyThe collective ideas—including political, economic, and religious ideas—that guide the way a culture views and talks about itself. of the society at the time, which is the collective ideas—including political, economic, and religious ideas—that guide the way a culture views and talks about itself. This cultural ideology, in turn, reflects the power structuresThe political, religious, educational, or social institutions that control or attempt to control the discourse of a society and often control the way literature is published, read, and interpreted. that control—or attempt to control—the discourse of a society and often control the way literature is published, read, and interpreted. Literature, then, as a societal discourse comments on and is influenced by the other cultural discourses, which reflect or resist the ideology that is based on the power structures of society.

Let’s turn to another example to illuminate these issues. One of the most influential books in American history was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), which Stowe wrote to protest slavery in the South before the Civil War.“Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture,” University of Virginia, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/sitemap.html. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was an instant bestseller that did much to popularize the abolitionist movement in the northern United States. Legend has it that when Abraham Lincoln met Stowe during the Civil War, he greeted her, by saying “So you’re the little woman that wrote the book that started this great war.” In the case of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, then, it’s clear that understanding the histories of slavery, abolitionism, and antebellum regional tensions can help us make sense of Stowe’s novel.

But history informs literature in less direct ways, as well. In fact, many literary scholars—in particular, New Historical scholars—would insist that every work of literature, whether it explicitly mentions a historical event or not, is shaped by the moment of its composition (and that works of literature shape their moment of composition in turn). The American history of the Vietnam war is a great example, for we continue to interpret and revise that history, and literature (including memoirs) is a key material product that influences that revision: think of Michael Herr’s Dispatches (1977); Philip Caputo’s A Rumor of War (1977); Bobbie Anne Mason’s In Country (1985); Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried (1990); Robert Olen Butler’s A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992); and, most recently, Karl Marlantes’s Matterhorn (2010).Michael Herr, Dispatches (New York: Vintage, 1977); Philip Carputo, A Rumor of War (New York: Ballantine, 1977); Bobbie Anne Mason, In Country (New York: HarperCollins, 2005); Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried (New York: Mariner, 2009); Robert Olen Butler, A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain: Stories (New York: Holt, 1992); Karl Marlantes, Matterhorn (New York: Atlantic Monthly, 2010).

Your Process

- Pick something you’ve read or watched recently. It doesn’t matter what you choose: the Harry Potter series, Twilight, The Hunger Games, even Jersey Shore or American Idol. Now reflect on what that book, movie, or television show tells you about your culture. What discourses or ideologies (values, priorities, concerns) does your cultural artifact reveal? Jot down your thoughts.

As you can see, authors influence their cultures and they, in turn, are influenced by the social, political, military, and economic concerns of their cultures. To review the connection between literature and history, let’s look at one final example, “London” (http://www.blakearchive.org/exist/blake/archive/object.xq?objectid=songsie.b.illbk.36&java=yes), written by the poet William Blake in 1794.

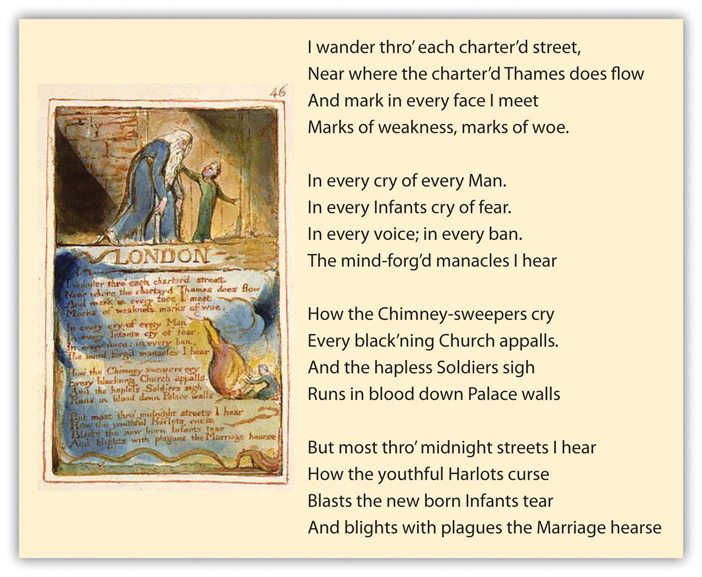

Illustration by William Blake for “London” from his Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794).

Unlike Yeats or Stowe, Blake does not refer directly to specific events or people from the late eighteenth century. Yet this poem directly confronts many of the most pressing social issues of Blake’s day. The first stanza, for example, refers to the “charter’d streets” and “charter’d Thames.” If we look up the meaning of the word “charter,” we find that the word has several meanings.Merriam-Webster Online, s.v. “charter,” http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/charter. “Charter” can refer to a deed or a contract. When Blake refers to “charter’d” streets, he might be alluding to the growing importance of London as a center of industry and commerce. A “charter” also defines boundaries and control. When Blake refers to “charter’d Thames,” then, he implies that nature—the Thames is the river that runs through London—has been constricted by modern society. If you look through the rest of the poem, you can see many other historical issues that a scholar might be interested in exploring: the plight of child laborers (“the Chimney-sweepers cry”); the role of the Church (“Every black’ning Church”), the monarchy (“down Palace walls”), or the military (“the hapless Soldiers sigh”) in English society; or even the problem of sexually transmitted disease (“blights with plagues the Marriage hearse”). You will also notice that Blake provided an etching for this poem and the poems that compose The Songs of Innocence (1789) and The Songs of Experience (in which “London” was published), so Blake is also engaging in the artistic movement of his day and the very production of bookmaking itself. And we would be remiss if we did not mention that Blake wrote these poems during the French Revolution (1789–99), where he initially hoped that the revolution would bring freedom to all individuals but soon recognized the brutality of the movement. That’s a lot to ask of a sixteen-line poem! But each of these topics is ripe for further investigation that might lead to an engaging critical paper.

When scholars dig into one historical aspect of a literary work, we call that process parallel readingParallel reading involves examining the literary text in light of other contemporary texts such as newspaper articles, religious pamphlets, economic reports, political documents, and so on.. Parallel reading involves examining the literary text in light of other contemporary texts: newspaper articles, religious pamphlets, economic reports, political documents, and so on. These different types of texts, considered equally, help scholars construct a richer understanding of history. Scholars learn not only what happened but also how people understood what happened. By reading historical and literary texts in parallel, scholars create, to use a phrase from anthropology, a thick descriptionA thick description focuses on very specific textual details and explains those details by showing how they reflect, demonstrate, or challenge the text’s culture. that centers the literary text as both a product and a contributor to its historical moment. A story might respond to a particular historical reality, for example, and then the story might help shape society’s attitude toward that reality, as Uncle Tom’s Cabin sparked a national movement to abolish slavery in the United States. To help us think through these ideas further, let’s look at a student’s research and writing process.