This is “Cash Flows from Operating Activities: The Indirect Method”, section 17.3 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

17.3 Cash Flows from Operating Activities: The Indirect Method

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the difference in the start of the operating activities section of the statement of cash flows when the indirect method is used rather than the direct method.

- Demonstrate the removal of both noncash items and nonoperating gains and losses in the application of the indirect method.

- Determine the effect caused by the change in the various connector accounts when the indirect method is used to present cash flows from operating activities.

- Identify the reporting classification for interest revenues, dividend revenues, and interest expense in creating a statement of cash flows and explain the controversy that resulted from this handling.

The Steps Followed in Applying the Indirect Method

Question: As mentioned, most organizations do not choose to present their operating activity cash flows using the direct method despite the preference of FASB. Instead, this information is almost universally shown within a statement of cash flows by means of the indirect method. How does the indirect method of reporting operating activity cash flows differ from the direct method?

Answer: The indirect method actually follows the same set of procedures as the direct method except that it begins with net income rather than the business’s entire income statement. After that, the same three steps demonstrated previously to determine the net cash flows from operating activities are followed although the mechanical application here is different.

- Noncash items are removed.

- Nonoperational gains and losses are removed.

- Adjustments are made, based on the monetary change occurring during the period in the various balance sheet connector accounts, to switch all remaining revenues and expenses from accrual accounting to cash accounting.

Removing Noncash and Nonoperating Items—The Indirect Method

Question: In the income statement presented in Figure 17.4 "Liberto Company Income Statement Year Ended December 31, Year One" for the Liberto Company, net income was reported as $100,000. This figure included depreciation expense (a noncash item) of $80,000 and a gain on the sale of equipment (an investing activity rather than an operating activity) of $40,000. In applying the indirect method, how are noncash items and nonoperating gains and losses removed from net income?

Answer: First, all noncash items within net income are eliminated. Depreciation is the example included here. As an expense, it is a negative component found within net income. To remove a negative, it is offset by a positive. Thus, adding back $80,000 serves to remove the impact of depreciation from the reporting company’s net income.

Second, all nonoperating items within net income are eliminated. Liberto’s gain on sale of equipment is reported within reported income. As a gain, it is a positive figure; it helped increase profits this period. To eliminate this gain, $40,000 must be subtracted from net income. The cash flows resulting from this transaction came from an investing activity and not an operating activity.

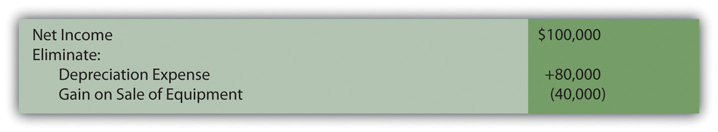

In applying the indirect method, as shown in Figure 17.7 "Operating Activity Cash Flows, Indirect Method—Elimination of Noncash and Nonoperating Balances", a negative is removed by addition; a positive is removed by subtraction.

Figure 17.7 Operating Activity Cash Flows, Indirect Method—Elimination of Noncash and Nonoperating Balances

- In the direct method, these two income statement amounts were simply omitted in arriving at the individual cash flows from operating activities.

- In the indirect method, they are both physically removed from income by reversing their effect.

The impact is the same in the indirect method as in the direct method; the balances are removed.

Converting Accrual Accounting Figures to Cash Balances—The Indirect Method

Question: After all noncash and nonoperating items are removed from net income, only the changes in the balance sheet connector accounts must be utilized to complete the conversion to cash. For Liberto, those balances were shown previously.

- Accounts receivable: up $19,000

- Inventory: down $12,000

- Prepaid rent: up $4,000

- Accounts payable: up $9,000

- Salary payable: down $5,000

Each of these increases and decreases was used in the direct method to turn accrual accounting figures into cash balances. That same process is followed in the indirect method. In determining cash flows from operating activities, how are changes in an entity’s connector accounts reflected in the application of the indirect method?

Answer: Although the procedures appear to be different, the same logic is applied in the indirect method as in the direct method. The change in each of the previous connector accounts discloses the difference in the accrual accounting amounts recognized in the income statement and the actual changes in cash. Here, though, the effect is measured on net income as a whole rather than on the individual revenue and expense accounts.

Accounts receivable increased by $19,000. This rise in the receivable balance shows that less money was collected than the sales made by Liberto during the period. Receivables go up because customers are slow to pay. This change results in a lower cash balance. Thus, the $19,000 is subtracted in arriving at the cash flow amount generated by operating activities. The cash received was actually less than the figure reported for sales that appears within the company’s net income. Subtract $19,000.

Inventory decreased by $12,000. A drop in the amount of inventory on hand indicates that less merchandise was purchased during the period. Buying less requires a smaller amount of cash to be paid. That leaves the cash balance higher. The $12,000 is added in arriving at the operating activity change in cash. Add $12,000.

Prepaid rent increased by $4,000. An increase in any prepaid expense shows that more of the asset was acquired during the year than was consumed. This additional purchase requires the use of cash; thus, the resulting cash balance is lower. The increase in prepaid rent necessitates a $4,000 subtraction in the operating activity cash flow computation. Subtract $4,000.

Accounts payable increased by $9,000. Any jump in a liability means that Liberto paid less cash during the period than the debts that were incurred. Postponing liability payments is a common method for saving cash to keep the reported balance high. In determining cash flows from operating activities, the $9,000 liability increase is added. Add $9,000.

Salary payable decreased by $5,000. Liability balances fall when additional payments are made. Such cash transactions are reflected in applying the indirect method by a $5,000 subtraction from net income. Subtract $5,000.

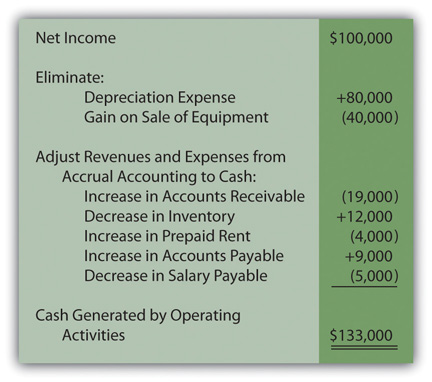

Therefore, if Liberto Company uses the indirect method to report its cash flows from operating activities, the information will be presented to decision makers as shown in Figure 17.8 "Liberto Company Statement of Cash Flows for Year One, Operating Activities Reported by Indirect Method".

Figure 17.8 Liberto Company Statement of Cash Flows for Year One, Operating Activities Reported by Indirect Method

As with the direct method (Figure 17.6 "Liberto Company Statement of Cash Flows for Year One, Operating Activities Reported by Direct Method"), the total here reflects a net cash inflow of $133,000 from the operating activities of this company. In both cases, the starting spot was net income (either as the entire income statement or as the single number). Then, all noncash items were removed as well as nonoperating gains and losses. Finally, the effect of changes in the various connector accounts that bridge the time period between accrual accounting recognition and the cash exchange are included so that only the cash flows from operating activities remain.

In reporting operating activity cash flows by means of the indirect method (Figure 17.8 "Liberto Company Statement of Cash Flows for Year One, Operating Activities Reported by Indirect Method"), the following pattern can be seen.

- A change in a connector account that is an asset is reflected on the statement in the opposite fashion. As shown previously, increases in both accounts receivable and prepaid rent are subtracted while a decrease in inventory is added.

- A change in a connector account that is a liability is included on the statement in an identical change. An increase in accounts payable is added whereas a decrease in salary payable is subtracted.

A quick visual comparison of the direct method (Figure 17.6 "Liberto Company Statement of Cash Flows for Year One, Operating Activities Reported by Direct Method") and the indirect method (Figure 17.8 "Liberto Company Statement of Cash Flows for Year One, Operating Activities Reported by Indirect Method") makes the two appear almost completely unrelated. However, when analyzed more closely, the same series of steps can be seen in each. They both begin with the income for the period. Noncash items and nonoperating gains and losses are removed. Changes in the connector accounts for the period are factored in so that only the cash from operating activities remains.

Test Yourself

Question:

The Hemingway Company reported net income last year of $354,000. Within that figure, depreciation expense of $37,000 was included. In addition, accounts receivable increased by $11,000 during the period. What amount of cash did this company generate from its operating activities?

- $306,000

- $328,000

- $380,000

- $402,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice c: $380,000.

Explanation:

Depreciation is a noncash expense that appears within net income as a negative. To remove it, the $37,000 figure is added. Addition counterbalances the original negative effect. The increase in accounts receivable means that customers were slow to pay this year. Credit sales were greater than the amount of cash received. The $11,000 is subtracted from net income to arrive at the lower cash figure. Thus, cash inflow from operating activities is $380,000 ($354,000 + $37,000 − $11,000).

Test Yourself

Question:

The Faulkner Corporation reported net income in Year One of $437,000. Accounts receivable at the start of the period totaled $26,000 but grew to $41,000 by the end of Year One. Beginning insurance payable was $7,000 but fell to an ending balance of $4,000. What amount of cash did Faulkner collect as a result of its operating activities?

- $419,000

- $425,000

- $449,000

- $455,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice a: $419,000.

Explanation:

Accounts receivable went from $26,000 to $41,000. The $15,000 increase indicates that credit sales were greater than cash collected. The $15,000 is subtracted from net income. Insurance payable fell by $3,000 ($7,000 to $4,000); thus, the amount paid was greater than the expense recognized. Cash was spent to reduce the liability. The $3,000 is also subtracted in arriving at the cash change. The cash inflow from operating activities is $419,000 ($437,000 net income − $15,000 and $3,000).

The Reporting of Dividends and Interest on the Statement of Cash Flows

Question: When listing cash flows from operating activities for the year ended December 31, 2010, EMC Corporation (a technology company) included an inflow of nearly $103 million labeled as “dividends and interest received” as well as an outflow of over $76 million shown as “interest paid.”

Unless a company is a bank or financing institution, dividend and interest revenues do not appear to relate to its central operating function. For most businesses, these cash inflows are fundamentally different from the normal sale of goods and services. Monetary amounts collected as dividends and interest resemble investing activity cash inflows because they are often generated from noncurrent assets. Similarly, interest expense payments are normally associated with noncurrent liabilities rather than resulting from daily operations. Interest expenditures could certainly be viewed as a financing activity cash outflow.

Dividend distributions are not in question here. They are labeled as financing activity cash outflows because they are made directly to stockholders. The issue is the classification of dividend and interest revenue collections and interest expense payments. Why is cash received as dividends and interest and cash paid as interest expense reported within operating activities on a statement of cash flows rather than as investing activities and financing activities?

Answer: Authoritative pronouncements that create U.S. GAAP are the subject of years of intense study, discussion, and debate. In this process, controversies often arise. When FASB issued its official standard on cash flows in 1987, three of the seven board members voted against passage. Their opposition, at least in part, came from the handling of interest and dividends. On page ten of Statement 95, Statement of Cash Flows, these three argue “that interest and dividends received are returns on investments in debt and equity securities that should be classified as cash inflows from investing activities. They believe that interest paid is a cost of obtaining financial resources that should be classified as a cash outflow for financing activities.”

The other board members were not convinced. Thus, inclusion of dividends collected, interest collected, and interest paid within an entity’s operating activity cash flows became a requirement of U.S. GAAP. Such disagreements arise frequently in the creation of official accounting rules.

The majority of the board apparently felt that—because these transactions occur on a regular ongoing basis—a better portrait of the organization’s cash flows is provided by inclusion within operating activities. At every juncture of financial accounting, multiple possibilities for reporting exist. Rarely is complete consensus ever achieved as to the most appropriate method of presenting financial information.

Talking With an Independent Auditor about International Financial Reporting Standards

Following is the conclusion of our interview with Robert A. Vallejo, partner with the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Question: Any company that follows U.S. GAAP and issues an income statement must also present a statement of cash flows. Cash flows are classified as resulting from operating activities, investing activities, or financing activities. Are IFRS rules the same for the statement of cash flows as those found in U.S. GAAP?

Rob Vallejo: Differences do exist between the two frameworks for the presentation of the statement of cash flows, but they are relatively minor. Probably the most obvious issue involves the reporting of interest and dividends that are received and paid. Under IFRS, interest and dividend collections may be classified as either operating or investing cash flows whereas, in U.S. GAAP, they are both required to be shown within operating activities. A similar difference exists for interest and dividend payments. These cash outflows can be classified as either operating or financing activities according to IFRS. For U.S. GAAP, interest payments are viewed as operating activities whereas dividend payments are considered financing activities.

Key Takeaway

Most reporting entities use the indirect method to report net cash flows from operating activities. This presentation begins with net income and then eliminates any noncash items (such as depreciation expense) as well as nonoperating gains and losses. Their impact on net income is reversed to create this removal. In addition, changes in each balance sheet connector account (such as accounts receivables, inventory, accounts payable, and salary payable) must also be utilized in converting from accrual accounting to cash. Changes in asset connectors are reversed in arriving at cash flows from operating activities whereas changes in liability connectors have the same impact (increases are added and decreases are subtracted). Cash transactions that result from interest revenue, dividend revenue, and interest expense are all reported within operating activities because they happen on a regular ongoing basis. However, some argue that interest and dividend collections are really derived from investing activities and interest payments relate to financing activities.