This is “Accounting for Product Warranties”, section 13.4 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

13.4 Accounting for Product Warranties

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the difference between an embedded and an extended product warranty.

- Account for the liability and expense incurred by a company that provides customers with an embedded warranty on a purchased product.

- Account for the amount received on the sale of an extended warranty and any subsequent costs incurred as a result of this warranty.

- Compute the average age of accounts payable.

Accounting for Embedded Product Warranties

Question: U.S. GAAP includes an embedded product warrantyAn obligation established by the sale of a product where the seller promises to fix or replace the product if it proves to be defective. as one type of loss contingency. A company sells merchandise such as a car or a microwave and agrees to fix certain problems if they arise within a specified period of time. The seller might promise, for example, to replace a car’s transmission if it breaks. Making the sale with this warranty attached is the past event that creates the contingency. However, the item acquired by the customer must break before the company has an actual loss. That outcome is uncertain.

In accounting for an embedded product warranty, several estimates are required:

- The approximate number of claims that can be expected

- The percentage of these claims will meet the requirements of the warranty

- The eventual cost from the average approved claim

As an example, General Electric reported on its December 31, 2010, balance sheet a liability for product warranties totaling over $1.5 billion. That is certainly not a minor obligation. In the notes to the financial statements, the company explains, “We provide for estimated product warranty expenses when we sell the related products. Because warranty estimates are forecasts that are based on the best available information—mostly historical claims experience—claims costs may differ from amounts provided.” How does a company record and report contingencies such as embedded product warranties?

Answer: In accounting for warranties, cash rebates, the collectability of receivables and other similar contingencies, the likelihood of loss is rarely an issue. These losses are almost always probable. For the accountant, the challenge is in arriving at a reasonable estimate of that loss. How many microwaves will break and have to be repaired? What percentage of cash rebate coupons will be presented by customers in the allotted time? How often will a car’s transmission need to be replaced?

Many companies utilize such programs on an ongoing basis so that data from previous offers will be available to help determine the amount of the expected loss. However, historical trends cannot be followed blindly. Officials still have to be alert for any changes that could impact previous patterns. For example, in bad economic periods, customers are more likely to take the time to complete the paperwork required to receive a cash rebate. Or, the terms may vary from one warranty program to the next. Even small changes in the wording of an offer can alter the expected number of claims.

To illustrate, assume that a retail store sells ten thousand compact refrigerators during Year One for $400 cash each. The product is covered by a warranty that extends until the end of Year Three. No claims are made in Year One but similar programs in the past have resulted in repairs having to be made on 3 percent of the refrigerators at an average cost of $90. Thus, the warranty on the Year One sales is expected to cost a total of $27,000 (10,000 units × 3 percent = 300 claims; 300 claims × $90 each = $27,000).

Although no repairs are made in Year One, the $27,000 liability is reported in that period. Immediate recognition is appropriate because the loss is both probable and subject to reasonable estimation. In addition, the matching principle states that expenses should be reported in the same period as the revenues they help generate. Because the revenue from the sale of the refrigerators is recognized in Year One (Figure 13.11 "Year One—Sale of Ten Thousand Compact Refrigerators for $400 Each"), the warranty expense resulting from those revenues is included at that time (Figure 13.12 "Year One—Recognize Expected Cost of Warranty Claims").

Figure 13.11 Year One—Sale of Ten Thousand Compact Refrigerators for $400 Each

Figure 13.12 Year One—Recognize Expected Cost of Warranty Claims

This warranty is in effect until the end of Year Three. Assume that repairs made in the year following the sale (Year Two) cost the company $13,000 but are made for these customers at no charge. When a refrigerator breaks, it is fixed as promised by the warranty. Because the expense has already been recognized in the year of sale (Figure 13.12 "Year One—Recognize Expected Cost of Warranty Claims"), these payments reduce the recorded liability as is shown in Figure 13.13 "Year Two—Payment for Repair Work Covered by Embedded Warranty". The actual costs create no additional impact on net income.

Figure 13.13 Year Two—Payment for Repair Work Covered by Embedded Warranty

At the end of Year Two, the liability balance in the general ledger holds a balance of $14,000 to reflect the expected warranty costs for Year Three ($27,000 original estimation less the $13,000 payout made for repairs to date). Because the warranty has not expired, company officials need to evaluate whether this $14,000 liability is still a reasonable estimation of the remaining costs to be incurred. If so, no further adjustment is made.

However, the original $27,000 was merely an estimate. More information is now available, some of which might suggest that $14,000 is no longer the best number to be utilized for the final year of the warranty. To illustrate, assume that a flaw has been found in the refrigerator’s design and that $20,000 (rather than $14,000) is now a better estimate of the costs to be incurred in the final year of the warranty.

The $14,000 balance is no longer appropriate. The reported figure is updated in Figure 13.14 "December 31, Year Two—Adjust Warranty Liability from $14,000 to Newly Expected $20,000" to provide a fair presentation of the data that is now available. Estimates should be changed at the point where new information provides a clearer vision of future events.

Figure 13.14 December 31, Year Two—Adjust Warranty Liability from $14,000 to Newly Expected $20,000

In this adjusting entry, the change in the expense is not recorded in the period of the sale. As discussed earlier, no retroactive restatements are made to figures previously reported unless fraud occurred or an estimate was held to be so unreasonable that it was not made in good faith.

Accounting for Extended Product Warranties

Question: Not all warranties are built into a sales transaction. Many retailers also offer extended product warrantiesAn obligation whereby the buyer of a product pays the seller for the equivalent of an insurance policy to protect against breakage or other harm to the product for a specified period of time. for an additional fee. For example, assume a business sells a high-definition television with an automatic one-year warranty. The buyer receives this warranty as part of the purchase agreement. The accounting for that first year is the same as just demonstrated; an estimated expense and liability are recognized at the time of sale.

However, an additional warranty for three more years is also offered at a price of $50. If on January 1, Year One, a customer buys a new television and also chooses to acquire this additional three-year coverage, what recording is made by the seller? Is an extended warranty purchased by a customer reported in the same manner as an automatic product warranty embedded within a sales contract?

Answer: Extended warranties, which are quite popular in many industries, are simply insurance policies. If the customer buys the coverage, the product is insured against breakage or other harm for the specified period of time. In most cases, the company is making the offer in an attempt to earn an extra profit. The seller hopes that the money received for the extended warranty will outweigh the eventual repair costs. Therefore, the accounting differs here from the process demonstrated previously for an embedded warranty that was provided to encourage the sale of the product. In that earlier example, all of the revenue as well as the related (but estimated) expense were recorded immediately.

By accepting money for an extended warranty, the seller agrees to provide services in the future. This contract is much like a gift card. The revenue cannot be recognized until the earning process is substantially complete. Thus, as shown in Figure 13.15 "January 1, Year One—Sale of Extended Warranty Covering Years Two through Four", the $50 received for the extended warranty on this television is initially recorded as “unearned revenue.” This balance is a liability because the company owes a specified service to the customer. As indicated previously, liabilities do not always represent future cash payments.

Figure 13.15 January 1, Year One—Sale of Extended Warranty Covering Years Two through Four

Note in Figure 13.15 "January 1, Year One—Sale of Extended Warranty Covering Years Two through Four" that no expense was estimated and recorded in connection with this warranty. As explained by the matching principle, expenses are not recognized until the related revenue is reported.

Because of the terms specified, this extended warranty does not become active until January 1, Year Two. The television is then covered for a three-year period. The revenue is recognized, most likely on a straight-line basis, over that time. Consequently, the $50 is reported at the rate of 1/3 per year or $16.66.

Figure 13.16 December 31, Year Two (as well as Three and Four)—Recognition of Revenue from Extended Warranty

In any period in which a repair must be made, the expense is recognized as incurred because revenue from this warranty contract is also being reported. For example, assume that on August 8, Year Two, a slight adjustment must be made to the television at a cost of $9. The product is under warranty so the customer is not charged for this service. The Year Two expense shown in Figure 13.17 "August 8, Year Two—Repair of Television under Warranty Contract" is being matched with the Year Two revenue recognized in Figure 13.16 "December 31, Year Two (as well as Three and Four)—Recognition of Revenue from Extended Warranty".

Figure 13.17 August 8, Year Two—Repair of Television under Warranty Contract

Test Yourself

Question:

A company sells a product late in Year One. The customer holds a one-year warranty on that product. The company believes the product will break in Year Two and have to be repaired at a cost of $16. Which of the following statements is true?

- If this is an embedded warranty that the customer received automatically when the product was acquired, the $16 expense is reported in Year One.

- If this is an extended warranty that the customer bought when the product was acquired, the $16 expense is reported in Year One.

- If this is an extended warranty that cost the customer $20, the company recognizes a $4 profit in Year One.

- If this is an embedded warranty that the customer received automatically when the product was acquired, revenue is recognized by the company in Year Two.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice a: If this is an embedded warranty that the customer received automatically when the product was acquired, the $16 expense is reported in Year One.

Explanation:

For an embedded warranty that comes with the purchase of a product, the expense (and related liability) is recognized immediately and no revenue is recorded for the warranty. For an extended warranty acquired by the customer, revenue is recognized over the period of coverage (like an insurance policy), and the expense is recognized as incurred. If an extended warranty was sold for $20, the expense and virtually all the revenue are reported in Year Two.

Computing the Age of Accounts Payable

Question: Previously, the current ratio (current assets divided by current liabilities) and the amount of working capitalFormula measuring an organization’s liquidity (the ability to pay debts as they come due); calculated by subtracting current liabilities from current assets. (current assets minus current liabilities) were discussed. Do investors and creditors analyze any other vital signs when analyzing the current liabilities reported by a business or other organization? Should decision makers be aware of any specific ratios or amounts in connection with current liabilities that provide especially insightful information about a company’s financial health and operations?

Answer: In studying current liabilities, the number of days a business takes to pay its accounts payable is usually a figure of interest. If a business begins to struggle, the time of payment tends to lengthen because of the difficulty in generating sufficient cash amounts. Therefore, an unexpected jump in this number is often one of the first signs of financial distress and warrants concern.

To determine the age of accounts payableA determination of the number of days that a company takes to pay for the inventory that it buys; computed by dividing accounts payable by the average inventory purchases made per day during the period. (or the number of days in accounts payable), the amount of inventory purchased during the year is first calculated:

cost of goods sold = beginning inventory + purchases – ending inventory.Thus,

purchases = cost of goods sold – beginning inventory + ending inventory.Using this computed purchases figure, the number of days that a company takes to pay its accounts payable on the average can be determined. Either the average accounts payable for the year can be used or just the ending balance.

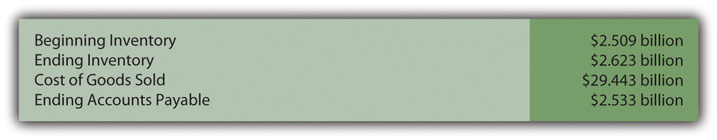

purchases/365 = average purchases per day accounts payable/average purchases per day = average age of accounts payableAs an illustration, the information presented in Figure 13.18 "Information from 2010 Financial Statements for Safeway Inc." comes from the 2010 financial statements for Safeway Inc.

Figure 13.18 Information from 2010 Financial Statements for Safeway Inc.

The total amount of inventory purchased by Safeway during 2010 was over $29 billion:

purchases = cost of goods sold – beginning inventory + ending inventory purchases = $29.443 billion - $2.509 billion + $2.623 billion purchases = $29.557 billion.The average purchases amount made each day during 2010 by Safeway was nearly $81 million:

purchases/365 $29.557/365 = $80.978 million.The average age of the reported accounts payable for Safeway at the end of 2010 was between thirty-one and thirty-two days:

accounts payable/average daily purchases $2.533 billion/$80.978 million = 31.28 days.To evaluate that number, a decision maker needs to compare it to (a) previous time periods for that company, (b) the typical payment terms for a business in that particular industry, and (c) comparable figures from other similar corporations. Interestingly, the same computation for 2008 showed that Safeway was taking 28.48 days to pay its accounts payable during that earlier period.

Key Takeaway

Many companies incur contingent liabilities as a result of product warranties. If the warranty is given to a customer along with a purchased item, an anticipated expense should be recognized at that time along with the related liability. If the reported cost of this type of embedded warranty eventually proves to be wrong, a correction is made when discovered assuming that the original estimate was made in good faith. Companies also sell extended warranties, primarily as a means of increasing profits. These warranties are recorded initially as liabilities (unearned revenue) with that amount reclassified to revenue over the time of the obligation. Subsequent costs are expensed as incurred to be in alignment with the matching principle. Thus, for extended warranties, expenses are not estimated and recorded in advance. Analysts often calculate the average age of accounts payable to determine how quickly liabilities are being paid as a vital sign used to indicate an entity’s financial health.

Talking with a Real Investing Pro (Continued)

Following is a continuation of our interview with Kevin G. Burns.

Question: Analysts often look closely at current liabilities when evaluating the future prospects of a company. Is there anything in particular that you look for when examining a company and the reported balances for its current liabilities?

Kevin Burns: For almost any company, there are a number of things that I look at in connection with current liabilities. I always have several questions where possible answers can concern me. I am interested in the terms of the current liabilities as well as the age of those liabilities. In other words, is the company current with its payments to vendors? Does the company have a significant amount of current liabilities but only a small amount of current assets? Or, stated more directly, can these liabilities be paid on time? Have current liabilities been growing while business has remained flat or grown much more slowly? Are any of the current liabilities to organizations controlled by corporate insiders? That always makes me suspicious so that, at the very least, I want more information. In sum, I like balance sheets where there are no potential conflicts of interest and the company is a reasonably fast payer of its debts.

Video Clip

(click to see video)Professor Joe Hoyle talks about the five most important points in Chapter 13 "In a Set of Financial Statements, What Information Is Conveyed about Current and Contingent Liabilities?".