This is “Accounting for Contingencies”, section 13.3 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

13.3 Accounting for Contingencies

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Define a commitment and explain the method by which it is reported.

- Define a contingency and explain the method by which it is reported.

- Explain the criteria that guide the reporting of a contingent loss.

- Describe the appropriate accounting for contingent losses that do not qualify for recognition at the present time.

- Describe the handling of a contingent loss that ultimately proves to be different from the originally estimated and recorded balance.

- Compare the reporting of contingent losses and contingent gains.

Commitments and Contingencies

Question: The December 31, 2010, balance sheet for E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (better known as DuPont) shows total liabilities of approximately $30.7 billion. Immediately following the liability section, a separate category titled “Commitments and Contingent Liabilities” is included but no monetary figure is presented. Note 19 to the company’s financial statements provides further details. In several pages of explanatory material, a number of future matters facing the company are described such as product warranties, environmental actions, litigation, and operating leases. In financial reporting, what is meant by the terms “commitments” and “contingencies?”

Answer:

Commitments. Commitments represent unexecuted contracts. A contract has been created (either orally or in writing) and all parties have agreed to the terms. However, the listed actions have not yet been performed.

For example, assume that a business places an order with a truck company for the purchase of a large truck. The business has made a commitmentAn unexecuted contract such as for the future purchase of inventory at a set price; amounts are not reported on the balance sheet or income statement because no transaction has yet occurred; disclosure of information within the financial statement notes is necessary. to pay for this new vehicle but only after delivery has been received. Although a cash payment will be required in the future, the specified event (conveyance of the truck) has not occurred. No transaction has taken place, so no journal entry is needed. The liability does not yet exist.

Information about such commitments is still of importance to decision makers because future cash payments will be required of the reporting company. However, events have not reached the point where all the characteristics of a liability are present. Thus, an extensive explanation about such commitments (as found in the notes for DuPont) is included in the notes to financial statements but no amounts are reported on either the income statement or the balance sheet. When a commitment is described, investors and creditors know that a step has been taken that will likely lead to a liability.

Contingencies. A contingencyA potential gain or loss that might eventually arise as a result of a past event; uncertainty exists as to the likelihood that a gain or loss will occur and the actual amount, if any, that will result. poses a different reporting quandary for the accountant. A past event has already occurred but the amount of the present obligation (if any) cannot yet be determined.

With a contingency, the uncertainty is about the ultimate outcome of an action that took place in the past. The accountant is not a fortune teller who can predict the future. To illustrate, assume Wysocki Corporation commits an act that is detrimental to the environment so that the federal government files a lawsuit for damages. The original action against the environment is the past event that creates the contingency. However, both the chance of losing the lawsuit and the possible amount of any penalties might not be known for several years. What, if anything, should be recognized in the interim?

Because companies prefer to avoid (or at least minimize) the recognition of losses and liabilities, authoritative guidelines are necessary to guide the appropriate reporting of contingencies. Otherwise, few if any contingencies would ever be reported.

According to U.S. GAAP, the recognition of a loss contingencyA potential loss resulting from a past event that must be recognized on an entity’s financial statements if it is deemed probable and the amount can be reasonably estimated. is required if the following are true:

- The loss is deemed to be probable.

- The amount of that loss can be reasonably estimated.

As soon as both of these criteria are met, the expected impact of the loss contingency must be recorded.

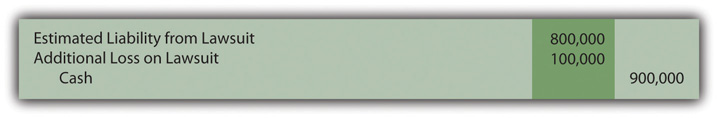

To illustrate, assume that the previous lawsuit for environmental damages was filed in Year One. Wysocki officials assess the situation. They believe that a loss is probable and that $800,000 is a reasonable estimation of the amount that will eventually have to be paid as a result of this litigation. Although this balance is only an estimate and the case may not be finalized for some time, the contingent loss is recognized, as can be seen in Figure 13.7 "Year One—Expected Loss from Lawsuit (Contingency)".

Figure 13.7 Year One—Expected Loss from Lawsuit (Contingency)

FASB has identified a number of examples of loss contingencies that are evaluated and reported in this same manner including:

- Collectability of receivables

- Obligations related to product warranties and product defects

- Risk of loss or damage of enterprise property by fire, explosion, or other hazards

- Threat of expropriation of assets

- Pending or threatened litigation

- Actual or possible claims and assessments

- Guarantees of indebtedness of others

Accounting Rules Used to Record Contingent Losses

Question: The likelihood of loss in connection with contingencies is not always going to be probable or subject to a reasonable estimation. These two criteria will be met in some but certainly not in all cases. What reporting is appropriate for a loss contingency that does not qualify for recording at the present time?

Answer: If a contingent loss is only reasonably possible (rather than probable) or if the amount of a probable loss does not lend itself to a reasonable estimation, only disclosure in the notes to the financial statements is necessary rather than actual recognition. Furthermore, a contingency where the chance of loss is viewed as merely remote can be omitted entirely from the financial statements.

Unfortunately, as discussed previously, official guidance provides little specific detail about what constitutes a probable, reasonably possible, or remote loss. At best, each of those terms seems vague. For example, within U.S. GAAP, “probable” is described as “likely to occur.” Thus, the professional judgment of the accountants and auditors must be relied on to determine the exact point in time when a contingent loss moves from reasonably possible to probable.

Not surprisingly, many companies contend that any future adverse effects from loss contingencies are only reasonably possible so that no actual amounts are reported on the balance sheet. Practical application of official accounting standards is not always theoretically pure, especially when the guidelines are nebulous.

Fixing an Incorrect Estimate

Question: Assume that a company recognizes a contingent loss because it is judged as probable and subject to a reasonable estimation. Eventually, most such guesses are likely to prove to be wrong, at least in some small amount. What happens when an estimate is reported in a set of financial statements and the actual total is later found to be different?

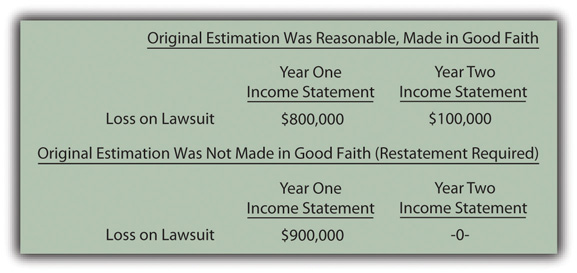

For example, as shown in Figure 13.7 "Year One—Expected Loss from Lawsuit (Contingency)", Wysocki Corporation recognized a loss of $800,000 in Year One because of a lawsuit involving environmental damage. Assume the case is eventually settled in Year Two for $900,000. How is the additional loss of $100,000 reported? It relates to an action taken in Year One but the actual amount is not finalized until Year Two. The difference is not apparent until the later date.

Answer: In Year One, because both criteria for reporting were met, an $800,000 loss was recognized on the income statement along with a corresponding liability. In addition, notes to the company’s financial statement will explain the nature of this lawsuit as well as the range of any reasonably possible losses. Decision makers analyzing the Wysocki Corporation should realize that the amount reported is not meant as a precise measure of the eventual loss. The same is true of all contingencies and other estimations. By the time that the exact amount of loss is determined, investors and creditors have already incorporated the original information into their decisions, including the uncertainty of the outcome. Restating the Year One loss to $900,000 does not allow them to undo and change decisions that were made in the past.

Consequently, no alteration is made in the $800,000 figure reported for Year One. The additional $100,000 loss is recorded in Year Two. The adjustment is recognized as soon as a better estimation (or final figure) is available. This approach is required to correct any reasonable estimate. Wysocki recognizes the updated balances through the journal entry shown in Figure 13.8 "Year Two—Settlement of Lawsuit at an Amount $100,000 More than Originally Reported" that removes the liability and records the remainder of the loss that has now been incurred.

Figure 13.8 Year Two—Settlement of Lawsuit at an Amount $100,000 More than Originally Reported

One important exception to this handling does exist. If the initial estimate is viewed as fraudulent—an attempt to deceive decision makers—the $800,000 figure reported in Year One is physically restated. It simply cannot continue to appear. All amounts in a set of financial statements have to be presented in good faith. Any reported balance that fails this essential test cannot be allowed to remain. Furthermore, even if company officials made no overt attempt to deceive, restatement is still required if they should have known that a reported figure was materially wrong. Such amounts were not reported in good faith; officials have been grossly negligent in reporting the financial information.

From a journal entry perspective, restatement of a previously reported income statement balance is accomplished by adjusting retained earnings. Revenues and expenses (as well as gains, losses, and any dividends paid figures) are closed into retained earnings at the end of each year. Thus, this account is where the previous year error now resides.

Upon discovery that the actual loss from the lawsuit is $900,000, this amount is reported by one of the two approaches presented in Figure 13.9 "Two Ways to Correct an Estimate". However, use of the second method is rare because accounting mistakes do not often reach this level of deceit or incompetence. An announcement that a company has had to “restate its earnings” is never a good sign.

Figure 13.9 Two Ways to Correct an Estimate

Test Yourself

Question:

The Red Company incurs a contingency in Year One. At that time, the company’s accountants believe that a loss of $200,000 is probable but a loss of $290,000 is reasonably possible. Nothing is settled by the end of Year Two. On that date, the accountants believe that a loss of $240,000 is probable but a loss of $330,000 is reasonably possible. All these estimations are viewed as reasonable. The contingency ends in Year Three when Red Company pays the other party $170,000 to settle the problem. What does Red Company recognize on its Year Three income statement?

- Gain (or Loss Recovery) of $30,000

- Gain (or Loss Recovery) of $70,000

- Gain (or Loss Recovery) of $120,000

- Gain (or Loss Recovery) of $160,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: Gain (or Loss Recovery) of $70,000.

Explanation:

A loss of $200,000 is recognized in Year One because that amount is viewed as probable. An additional $40,000 loss is recognized in Year Two so that the total loss reported to date corresponds to the estimated $240,000 probable amount. However, the company does not lose all $240,000 that has now been recognized but only $170,000. The reduction in the reported loss increases net income by the $70,000 difference and is shown as either a gain or a loss recovery.

Gain Contingencies

Question: The previous discussion focused entirely on the accounting that is required for loss contingencies. Companies obviously can also have gain contingenciesA potential gain resulting from a past event that is not recognized in an entity’s financial statements until it actually occurs due to the conservatism inherent in financial accounting.. In a lawsuit, for example, one party might anticipate winning $800,000 but eventually collect $900,000. Are the rules for reporting gain contingencies the same as those applied to loss contingencies?

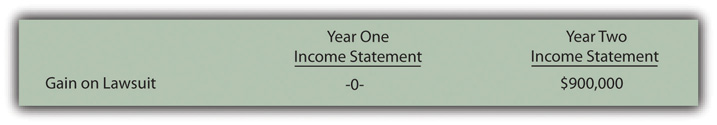

Answer: As a result of the conservatism inherent in financial accounting, the timing used in the recognition of gains does not follow the same rules applied to losses. Losses are anticipated when they become probable; that has long been a fundamental rule of financial reporting. The recognition of gains is delayed until they actually occur (or, at least until they reach the point of being substantially complete). Disclosure in the notes is still important but the decision as to whether the outcome is probable or reasonably possible is irrelevant in reporting a gain. As reflected in Figure 13.10 "Reporting a Gain Contingency", gains are not anticipated for reporting purposes.

Figure 13.10 Reporting a Gain Contingency

Test Yourself

Question:

The Blue Company files a lawsuit against another company in Year One and thinks there is a good chance for a win. At that time, the company’s accountants believe that a gain of $200,000 is probable but a gain of $290,000 is reasonably possible. Nothing is settled by the end of Year Two. On that date, the accountants believe that a gain of $240,000 is probable but a gain of $330,000 is reasonably possible. The contingency is settled in Year Three when Blue Company collects $170,000. What does Blue Company recognize on its Year Three income statement?

- Decrease in income of $30,000

- Decrease in income of $70,000

- Decrease in income of $120,000

- Increase in income of $170,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice d: Increase in income of $170,000.

Explanation:

As a gain contingency, no amount will be recognized until the point where substantial completion is reached. Consequently, no gain or loss is reported in either Year One or Year Two despite the optimism that a gain will be achieved. Thus, the entire amount of the gain is recorded when the case is settled in Year Three. That final event increases net income by $170,000.

Talking with an Independent Auditor about International Financial Reporting Standards

Following is a continuation of our interview with Robert A. Vallejo, partner with the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Question: According to U.S. GAAP, a contingent loss must be recognized when it is probable and a reasonable estimation of the amount can be made. That rule has been in place now for over thirty years and is well understood in this country. Are contingent losses handled in the same way by IFRS?

Robert Vallejo: The theory is the same under IFRS but some interesting and subtle differences do exist. If there is a probable future outflow of economic benefits and the company can form a reliable estimate, then that amount must be recognized. However, the term “probable” is defined as “more likely than not” which is easier to reach than the U.S. GAAP equivalent. Thus, the reporting of more contingent losses is likely under IFRS than currently under U.S. GAAP.

IAS 37, Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets, states that the amount recorded should be the best estimate of the expenditure that would be required to settle the present obligation at the balance sheet date. That is the best estimate of the amount that an entity would rationally pay to settle the obligation at the balance sheet date or to transfer it to a third party. Under U.S. GAAP, if there is a range of possible losses but no best estimate exists within that range, the entity records the low end of the range. Under IFRS, the entity records the midpoint of the range. That is a subtle difference in wording, but it is one that could have a significant impact on financial reporting for organizations where expected losses exist within a very wide range.

In July 2010, the FASB published an exposure draft, Disclosure of Certain Loss Contingencies, as investors and other users of financial reporting had expressed concerns that disclosures about loss contingencies. Many felt that existing guidance does not provide adequate and timely information to assist them in assessing the likelihood, timing, and magnitude of future cash outflows associated with loss contingencies. After receiving comments from constituents, the FASB is re-deliberating the need to update existing U.S. GAAP.

Key Takeaway

Entities often enter into contractual arrangements. Prior to performing the requirements of the contract, financial commitments frequently exist. They are future obligations that do not yet qualify as liabilities. For accounting purposes, they are only described in the notes to the financial statements. In contrast, contingencies are potential liabilities that might result because of a past event. The likelihood of loss or the actual amount of the loss both remain uncertain. Loss contingencies are recognized when their likelihood is probable and this loss is subject to a reasonable estimation. Reasonably possible contingent losses are only described in the notes whereas potential losses that are only remote can be omitted entirely from a company’s financial statements. Eventually, such estimates often prove to be incorrect and are normally fixed when first discovered. However, if fraud, either purposely or through gross negligence, has occurred, the amounts reported in prior years are restated. Contingent gains are only reported to decision makers through disclosure within the notes to the financial statements.