This is “The Problem with Estimations”, section 7.3 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.3 The Problem with Estimations

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Record the impact of discovering that a specific receivable is uncollectible.

- Understand the reason an expense is not recognized when a receivable is deemed to be uncollectible.

- Record the collection of a receivable that has previously been written off as uncollectible.

- Recognize that estimated figures often prove to be erroneous, but changes in previous year figures are not made if the reported balance was a reasonable estimate.

The Write-Off of an Uncollectible Account

Question: The company in the above illustration expects to collect cash from its receivables that will not materially differ from $93,000. The $7,000 bad debt expense is recorded in the same period as the revenue through a Year One adjusting entry.

What happens when an actual account is determined to be uncollectible? For example, assume that on March 13, Year Two, a $1,000 balance is judged to be worthless. The customer dies, declares bankruptcy, disappears, or just refuses to make payment. This $1,000 is not a new expense. A total of $7,000 was already anticipated and recognized in Year One. It is merely the first discovery. How does the subsequent write-off of an uncollectible receivable affect the various T-account balances?

Answer: When an account proves to be uncollectible, the receivable T-account is decreased. The $1,000 balance is simply removed. It is not viewed as an asset because it has no future economic benefit. Furthermore, the amount of bad accounts within the receivables is no longer anticipated as $7,000. Because this first worthless receivable has been identified and eliminated, only $6,000 remains in the allowance for doubtful accounts.

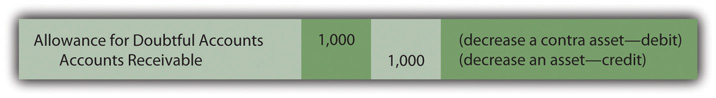

In Figure 7.4 "Journal Entry during Year Two—Write-Off of Specific Account as Uncollectible", the journal entry is shown to write off this account. Throughout the year, this entry is repeated whenever a balance is found to be worthless. No additional expense is recognized. The expense was estimated and recorded in the previous period to comply with accrual accounting and the matching principle.

Figure 7.4 Journal Entry during Year Two—Write-Off of Specific Account as Uncollectible

Two basic steps in the recording of doubtful accounts are shown here.

- Reporting of uncollectible accounts in the year of sale based on estimation. The amount of bad accounts is estimated whenever financial statements are to be produced. An adjusting entry then recognizes the expense in the same period as the sales revenue. It also increases the allowance for doubtful accounts (to reduce the reported receivable balance to its anticipated net realizable value).

- Write-off of an account judged to be uncollectible. Subsequently, whenever a specific account is deemed to be worthless, the balance is removed from both the accounts receivable and the allowance-for-doubtful-accounts T-accounts. The related expense has been recognized previously and is not affected by the removal of a specific uncollectible account.

These two steps are followed consistently throughout the reporting of sales made on account and the subsequent collection (or write-off) of the balances.

Test Yourself

Question:

Near the end of Year One, a company is beginning to prepare financial statements. Accounts receivable total $320,000, but the net realizable value is only expected to be $290,000. On the last day of the year, the company realizes that a $3,000 receivable has become worthless and must be written off. The debtor had declared bankruptcy and will never be able to pay. What is the impact of this decision?

- The net amount reported for receivables goes down.

- The net amount reported for receivables stays the same.

- The net amount reported for receivables goes up.

- A company cannot write off an account at the end of the year in this manner.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: The net amount reported for receivables stays the same.

Explanation:

The allowance for doubtful accounts is $30,000 ($320,000 total less a net realizable value of $290,000). Writing off a $3,000 account reduces the receivable total from $320,000 to $317,000. In addition, the allowance drops from $30,000 to $27,000. The net balance to be reported remains $290,000 ($317,000 less $27,000). The company still expects to collect $290,000 from its receivables and reports that balance. Writing an account off as uncollectible does not impact the anticipated figure.

Collecting Accounts Previously Written Off

Question: An account receivable is judged as a bad debt and an adjusting entry is prepared to remove it from the ledger accounts. What happens then? After a receivable has been written off as uncollectible, does the company cease in its attempts to collect the amount due from the customer?

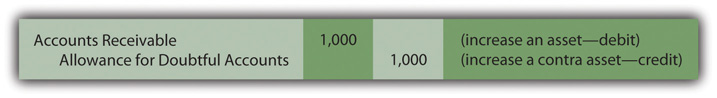

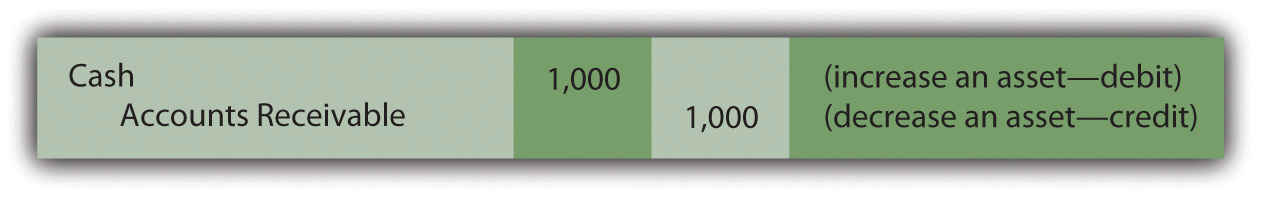

Answer: Organizations always make every possible effort to recover money they are owed. Writing off an account simply means that the chances of collection are deemed to be slim. Efforts to force payment will continue, often with increasingly aggressive techniques. If money is ever received from a written off account, the company first reinstates the account by reversing the earlier entry (Figure 7.5 "Journal Entry—Reinstate Account Previously Thought to Be Worthless"). Then, the cash received is recorded in the normal fashion (Figure 7.6 "Journal Entry—Collection of Reinstated Account"). The two entries shown here are appropriate if the above account is eventually collected from this customer. Some companies combine these entries by simply debiting cash and crediting the allowance. That single entry has the same overall impact as Figure 7.5 "Journal Entry—Reinstate Account Previously Thought to Be Worthless" and Figure 7.6 "Journal Entry—Collection of Reinstated Account".

Figure 7.5 Journal Entry—Reinstate Account Previously Thought to Be Worthless

Figure 7.6 Journal Entry—Collection of Reinstated AccountMany companies combine these two entries for convenience. The debit to accounts receivable in the first entry exactly offsets the credit in the second. Thus, the same recording impact is achieved by simply debiting cash and crediting the allowance for doubtful accounts. However, the rationale for that single entry is not always as evident to a beginning student.

Reporting an Incorrect Estimation

Question: In this illustration, at the end of Year One, the company estimated that $7,000 of its accounts receivable will ultimately prove to be uncollectible. However, in Year Two, that figure is likely to be proven wrong. It is merely a calculated guess. The actual amount might be $6,000 or $8,000 or many other numbers. When the precise figure is known, does a company return to its Year One financial statements and adjust them to the correct balance? Should a company continue reporting an estimated figure for a previous year even after it has been shown to be incorrect?

Answer: According to U.S. GAAP, if a number in an earlier year is reported based on a reasonable estimation, any subsequent differences with actual amounts are not handled retroactively (by changing the previously released figures). For example, if uncollectible accounts here prove to be $8,000, the company does not adjust the balance reported as the Year One bad debt expense from $7,000 to $8,000. It continues to report $7,000 on the income statement for that period even though that number is now known to be wrong.

There are several practical reasons for the accountant’s unwillingness to adjust previously reported estimations unless they were clearly unreasonable or fraudulent:

- Most decision makers are well aware that many reported figures represent estimates. Discrepancies are expected and should be taken into consideration when making decisions based on numbers presented in a set of financial statements. In analyzing this company and its financial health, educated investors and creditors anticipate that the total of bad accounts will ultimately turn out to be an amount that is not materially different from $7,000 rather than exactly $7,000.

- Because an extended period of time often exists between issuing statements and determining actual balances, most parties will have already used the original information to make their decisions. Knowing the exact number now does not allow them to undo those prior actions. There is no discernable benefit from having updated figures as long as the original estimate was reasonable.

- Financial statements contain numerous estimations and nearly all will prove to be inaccurate to some degree. If exactness were required, correcting each of these previously reported figures would become virtually a never-ending task for a company and its accountants. Scores of updated statements might have to be issued before a “final” set of financial figures became available after several years. For example, the exact life of a building might not be known for 50 years or more. Decision makers want information that is usable as soon as possible. Speed in reporting is far more important than absolute precision.

- At least theoretically, half of the differences between actual and anticipated results should make the reporting company look better and half make it look worse. If so, the corrections needed to rectify all previous estimation errors will tend to offset and have little overall impact on a company’s reported income and financial condition.

Thus, no change is made in financial figures that have already been released whenever a reasonable estimation proves to be wrong. However, differences that arise should be taken into consideration in creating current and subsequent statements. For example, if the Year One bad debts were expected to be 7 percent, but 8 percent actually proved to be uncollectible, the accountant might well choose to use a higher percentage at the end of Year Two to reflect this new knowledge.

Recording Receivable Transactions in Subsequent Years

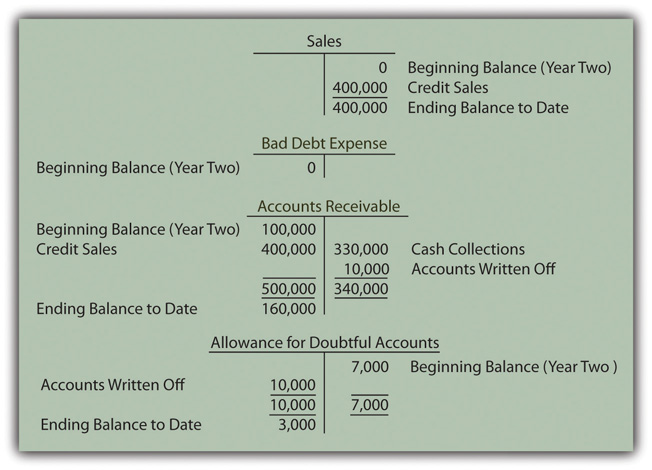

Question: To carry the previous illustration one step further, assume that $400,000 in new credit sales are made during Year Two while cash of $330,000 is collected. Uncollectible receivables totaling $10,000 are written off in that year. What balances appear in the various T-accounts at the end of a subsequent year to reflect sales, collections, and the write-off of uncollectible receivables?

Answer: Sales and bad debt expense were reported previously for Year One. However, as income statement accounts, both were closed out in order to begin Year Two with zero balances. They are temporary accounts. In contrast, accounts receivable and the allowance for doubtful accounts appear on the balance sheet and retain their ending figures going into each subsequent period. They are permanent accounts. Thus, these two T-accounts still show $100,000 and $7,000 respectively at the beginning of Year Two.

Assuming that no adjusting entries have yet been recorded, these four accounts hold the balances shown in Figure 7.7 "End of Year Two—Sales, Receivables, and Bad Debt Balances" at the end of Year Two. Notice that the bad debt expense account remains at zero until the end-of-year estimation is made and recorded.

Figure 7.7 End of Year Two—Sales, Receivables, and Bad Debt Balances

Residual Balance in the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

Question: In the T-accounts in Figure 7.7 "End of Year Two—Sales, Receivables, and Bad Debt Balances", the balances represent account totals for Year Two prior to year-end adjusting entries. Why does a debit balance of $3,000 appear in the allowance for doubtful accounts before recording the necessary adjustment for the current year? When a debit balance is found in the allowance for doubtful accounts, what does this figure signify?

Answer: When Year One financial statements were produced, $7,000 was estimated as the amount of receivables that would eventually be identified as uncollectible. In Year Two, the actual total written off turned out to be $10,000. The original figure was too low by $3,000. This difference is now reflected by the debit remaining in the allowance account. Until the estimation for the current year is determined and recorded, the balance residing in the allowance account indicates a previous underestimation (an ending debit balance) or overestimation (a credit) of the amount of worthless accounts.The $3,000 debit figure is assumed here for convenience to be solely the result of underestimating uncollectible accounts in Year One. Several other factors may also be present. For example, the balance in the allowance for doubtful accounts will be impacted by credit sales made in the current year that are discovered to be worthless before the end of the period. Such accounts actually reduce the allowance T-account prior to the recognition of an expense. The residual allowance balance is also affected by the collection of accounts that were written off as worthless in an earlier year. As described earlier, the allowance is actually increased by that event. However, the financial reporting is not altered by the actual cause of the final allowance figure.

Key Takeaway

Bad debt expense is estimated and recorded in the period of sale to correspond with the matching principle. Subsequent write-offs of specific accounts do not affect the expense further. Rather, both the asset and the allowance for doubtful accounts are decreased at that time. If a written off account is subsequently collected, the allowance account is increased to reverse the previous impact. Estimation errors are anticipated in financial accounting; perfect predictions are rarely possible. When the amount of uncollectible accounts differs from the original figure recognized, no retroactive adjustment is made to restate earlier figures as long as a reasonable estimate was made. Decisions have already been made by investors and creditors based on the original data and cannot be reversed. These decision makers should have understood that the information they were using could not possibly reflect exact amounts.