This is “Accounting for Uncollectible Accounts”, section 7.2 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.2 Accounting for Uncollectible Accounts

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Understand the reason for reporting a separate allowance account on the balance sheet in connection with accounts receivable.

- Know that bad debt expenses must be anticipated and recorded in the same time period as the related sales revenue to conform to the matching principle.

- Prepare the adjusting entry to reduce accounts receivable to net realizable value and recognize the resulting bad debt expense.

The Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

Question: Based on the information provided by Dell Inc., companies seem to maintain two separate ledger accounts in order to report accounts receivables at net realizable value. One is the sum of all accounts outstanding and the other is an estimation of the amount within the total that will never be collected. Interestingly, the first is a fact and the second is an opinion. The two are then combined to arrive at the net realizable value figure shown on the balance sheet. Is the amount reported for accounts receivable actually the net of the total due from customers less the anticipated doubtful accounts?

Answer: Yes, companies do maintain two separate T-accounts for accounts receivables, but that is solely because of the uncertainty involved. If the balance to be collected was known, one account would suffice for reporting purposes. However, that level of certainty is rarely possible.

- An accounts receivable T-account monitors the total due from all of a company’s customers.

- A second account (often called the allowance for doubtful accountsA contra asset account reflecting the amount of accounts receivable that the reporting company estimates will eventually fail to be collected, also referred to as the allowance for uncollectible accounts. or the allowance for uncollectible accounts) reflects the estimated amount that will eventually have to be written off as uncollectible.

Whenever a balance sheet is produced, these two accounts are netted to arrive at net realizable value, the figure to be reported for this particular asset.

The allowance for doubtful accounts is an example of a contra accountAn offset to a reported account that decreases the total balance to a net amount; in this chapter, the allowance for doubtful accounts reduces reported accounts receivable to the amount expected to be collected., one that always appears with another account but as a direct reduction to lower the reported value. Here, the allowance decreases the receivable balance to its estimated net realizable value. As a contra asset account, debit and credit rules are applied that are opposite of the normal asset rules. Thus, the allowance increases with a credit (creating a decrease in the net receivable balance) and decreases with a debit. The more accounts receivable a company expects to be bad, the larger the allowance. This increase, in turn, reduces the net realizable value shown on the balance sheet.

By establishing two T-accounts, Dell can manage a total of $6.589 billion in accounts receivables while setting up a separate allowance balance of $96 million. As a result, the reported figure—as required by U.S. GAAP—is the estimated net realizable value of $6.493 billion.

Anticipating Bad Debt Expense

Question: Accounts receivable and the offsetting allowance for doubtful accounts are netted with the resulting figure reported as an asset on the balance sheet.Some companies include both accounts on the balance sheet to indicate the origin of the reported balance. Others show only the single net figure with explanatory information provided in the notes to the financial statements. How does the existence of doubtful accounts affect the income statement? Sales are made on account, but a portion of the resulting receivables must be reduced because collection is rarely expected to be 100 percent. Does the presence of bad accounts create an expense for the reporting company?

Answer: Previously, an expense was defined as a measure of decreases in or outflows of net assets (assets minus liabilities) incurred in connection with the generation of revenues. If receivables are recorded that will eventually have to be decreased because they cannot be collected, an expense must be recognized. In financial reporting, terms such as bad debt expenseEstimated expense from making sales on account to customers who will never pay; because of the matching principle, the expense is recorded in the same period as the sales revenue., “doubtful accounts expense,” or “the provision for uncollectible accounts” are often encountered for that purpose.

The inherent uncertainty as to the amount of cash that will be received affects the physical recording process. How is a reduction reported if the amount will not be known until sometime in the future?

To illustrate, assume that a company makes sales on account to one hundred different customers late in Year One for $1,000 each. The earning process is substantially complete at the time of sale and the amount of cash to be received can be reasonably estimated. According to the revenue realization principle within accrual accounting, the company should immediately recognize the $100,000 revenue generated by these transactions.Because the focus of the discussion here is on accounts receivable and their collectability, the recognition of cost of goods sold as well as the possible return of any merchandise will be omitted at this time.

Figure 7.1 Journal Entry—Year One—Sales Made on Credit

Assume further that the company’s past history and other relevant information lead officials to estimate that approximately 7 percent of all credit sales will prove to be uncollectible. An expense of $7,000 (7 percent of $100,000) is anticipated because only $93,000 in cash is expected from these receivables rather than the full $100,000 that was recorded.

The specific identity and the actual amount of these bad accounts will probably not be known for many months. No physical evidence exists at the time of sale to indicate which will become worthless (buyers rarely make a purchase and then immediately declare bankruptcy or leave town). For convenience, accountants wait until financial statements are to be produced before making this estimation of net realizable value. The necessary reduction is then recorded by means of an adjusting entry.

In the adjustment, an expense is recognized. This method of presentation has a long history in financial accounting. However, recently FASB has been discussing whether a direct reduction in revenue might not be a more appropriate approach to portray bad debts. Financial accounting rules are under constant scrutiny, which leads to continual evolution.

Bad Debts and the Matching Principle

Question: This company holds $100,000 in accounts receivable but only expects to collect $93,000 based on available evidence. The $7,000 reduction in the asset is an expense. When should the expense be recognized? These sales were made in Year One but the specific identity of the customers who fail to pay and the actual uncollectible amounts will not be determined until Year Two. Should bad debt expense be recognized in the same year as the sales by relying on an estimate or delayed until the actual results are eventually finalized? How is the uncertainty addressed?

Answer: This situation illustrates how accrual accounting plays such a key role within financial reporting. As discussed previously, the timing of expense recognition according to accrual accounting is based on the matching principle. Where possible, expenses are recorded in the same period as the revenues they helped generate. The guidance is clear. Thus, every company should handle uncollectible accounts in the same manner. The expected expense is the result of making sales to customers who ultimately will never pay. Because the revenue was reported at the time of sale in Year One, the related expense is also recognized in that year. This handling is appropriate according to accrual accounting even though the $7,000 is only an estimated figure.

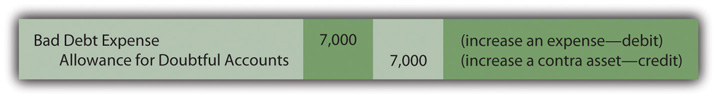

Therefore, as shown in Figure 7.2 "Adjusting Entry—End of Year One—Recognition of Bad Debt Expense for the Period", when the company produces financial statements at the end of Year One, an adjusting entry is made to (1) reduce the receivables balance to its net realizable value and (2) recognize the expense in the same period as the related revenue.

Figure 7.2 Adjusting Entry—End of Year One—Recognition of Bad Debt Expense for the Period

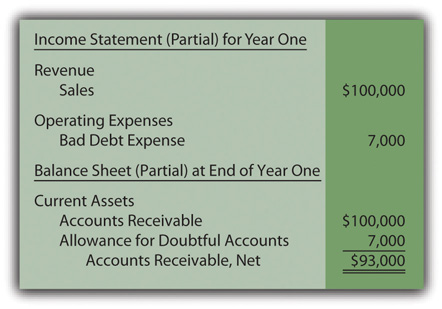

After this entry is made and posted to the ledger, the Year One financial statements contain the information shown in Figure 7.3 "Year One—Financial Statements" based on the adjusted T-account balances (assuming for convenience that no other sales were made during the year):

Figure 7.3 Year One—Financial Statements

From this information, anyone studying these financial statements should understand that an expense estimated at $7,000 was incurred this year because the company made sales of that amount that will never be collected. In addition, year-end accounts receivable total $100,000 but have an anticipated net realizable value of only $93,000. Neither the $7,000 nor the $93,000 figure is expected to be exact but the eventual amounts should not be materially different. With an understanding of financial accounting, the reported information is clear.

Test Yourself

Question:

A company’s general ledger includes a balance for bad debt expense and another for the allowance for doubtful accounts. Which of the following statements is true?

- Both bad debt expense and the allowance for doubtful accounts are reported on the income statement.

- Both bad debt expense and the allowance for doubtful accounts are reported on the balance sheet.

- Bad debt expense is reported on the income statement; the allowance for doubtful accounts is reported on the balance sheet.

- Bad debt expense is reported on the balance sheet; the allowance for doubtful accounts is reported on the income statement.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice c: Bad debt expense is reported on the income statement; the allowance for doubtful accounts is reported on the balance sheet.

Explanation:

Bad debt expense is reported on the income statement to show the amount of sales recognized this year that the company estimates will not be collected. The allowance for doubtful accounts is a contra asset account reported on the balance sheet to reduce accounts receivable to their estimated net realizable value.

The Need for a Separate Allowance Account

Question: When financial statements are prepared, an expense must be recognized and the receivable balance reduced to net realizable value. However, in the previous adjusting entry, why was the accounts receivable account not directly decreased by $7,000 to the anticipated balance of $93,000? This approach is simpler as well as easier to understand. Why was the $7,000 added to this contra asset account? In reporting receivables, why does the accountant go to the trouble of creating a separate allowance for reduction purposes?

Answer: When the company prepares the adjustment in Figure 7.2 "Adjusting Entry—End of Year One—Recognition of Bad Debt Expense for the Period" at the end of Year One, the actual accounts that will not be collected are unknown. Officials are only guessing that $7,000 will prove worthless. Plus, on the balance sheet date, the company does hold $100,000 in accounts receivable. That figure cannot be reduced directly until the specific identity of the accounts to be written off has been established. Utilizing a separate allowance allows the company to communicate the expected amount of cash while still maintaining a record of all balances in the accounts receivable T-account.

Key Takeaway

A sale on account and the eventual decision that the cash will never be collected can happen months, if not years, apart. During the interim, bad debts are estimated and recorded on the income statement as an expense and on the balance sheet by means of an allowance account, a contra asset. Through this process, the receivable balance is shown at net realizable value while expenses are recognized in the same period as the sale to correspond with the matching principle. When financial statements are prepared, an estimation of the uncollectible amounts is made and an adjusting entry recorded. Thus, the expense, the allowance account, and the accounts receivable are all presented according to financial accounting standards.