This is “Three Traders and Redistribution with Trade”, section 3.4 from the book Policy and Theory of International Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.4 Three Traders and Redistribution with Trade

Learning Objectives

- Learn how changes in the numbers of traders changes the terms of trade and affects the final consumption possibilities.

- Learn that an increase in competition causes a redistribution of income.

- Learn the importance of the profit-seeking assumption to the outcome.

- Learn how one’s role as a seller or buyer in a market, affects one’s preference for competition.

Suppose for many days, months, or years, Farmer Smith and Farmer Jones are the only participants in the market. However, to illustrate the potential for winners and losers from trade, let us extend the pure exchange model to include three farmers rather than two. Suppose that one day a third farmer arrives at the market where Farmer Jones and Farmer Smith conduct their trade. The third farmer is Farmer Kim, and he arrives at the market with an endowment of ten apples.

The main effect of Farmer Kim’s arrival is to change the relative scarcity of apples to oranges. On this day, the total number of apples available for sale has risen from ten to twenty. Thus apples are relatively more abundant, while oranges are relatively scarcer. The change in relative scarcities will undoubtedly affect the terms of trade that is decided on during this second day of trading.

Farmer Smith, as a seller of oranges (the relatively scarcer good), now has a stronger negotiating position than he had on the previous day. Farmer Jones and Farmer Kim, as sellers of apples, are now competing against each other. With the increased supply of apples at the market, the price of apples in exchange for oranges can be expected to fall. Likewise, the price of oranges in exchange for apples is likely to rise. This means that Farmer Smith can negotiate exchanges that yield more apples for each orange compared with the previous day.

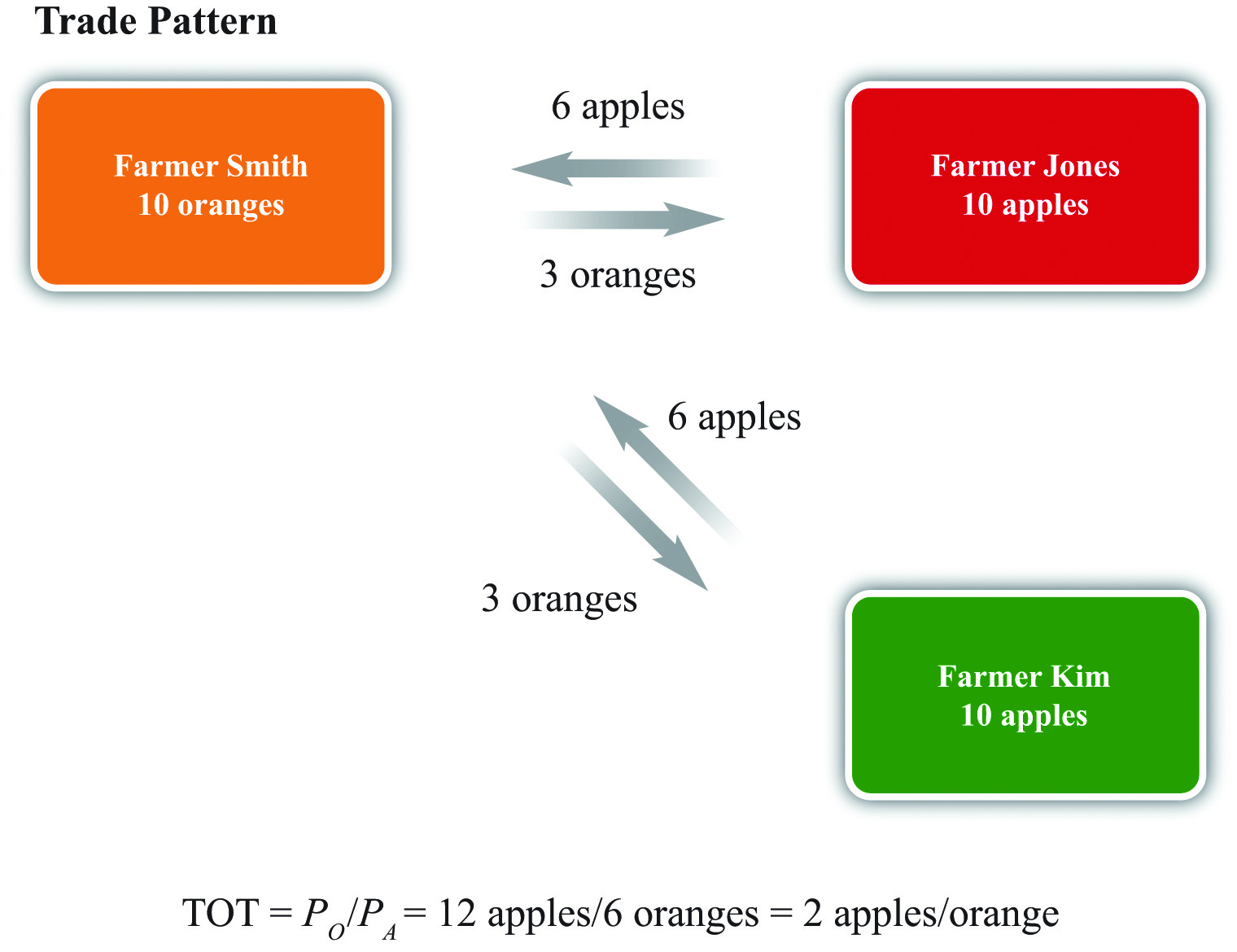

Suppose Farmer Smith negotiates a trade of three oranges for six apples with each of the two apple sellers (see Figure 3.2 "Three-Farmer Trade Pattern"). After trade, Farmer Smith will have twelve apples and four oranges for consumption. Farmers Jones and Kim will each have three oranges and four apples to consume.

Figure 3.2 Three-Farmer Trade Pattern

As before, assuming that all three farmers entered into these trades voluntarily, it must hold that each one is better off than he would be in the absence of trade. However, we can also compare the fate of each farmer relative to the previous week. Farmer Smith is a clear winner. He can now consume twice as many apples and the same number of oranges as in the previous week. Farmer Jones, on the other hand, loses due to the arrival of Farmer Kim. He now consumes fewer oranges and the same number of apples as in the previous week. As for Farmer Kim, presumably he made no earlier trades. Since he was free to engage in trade during the second week, and he agreed to do so, he must be better off.

It is worth noting that we assume here that each of the farmers, but especially Farmer Smith, is motivated by profit. Farmer Smith uses his bargaining ability because he knows that by doing so he can get a better deal and, ultimately, more goods to consume. Suppose for a moment, however, that Farmer Smith is not motivated by profit but instead cares about friendship. Because he and Farmer Jones had been the only traders in a market for a long period of time before the arrival of Farmer Kim, surely they got to know each other well. When Farmer Kim arrives, it is conceivable Smith will recognize that by pursuing profit, his friend Farmer Jones will lose out. In the name of friendship, Smith might refuse to trade with Kim and continue to trade at the original terms of trade with Jones. In this case, the outcome is different because we have changed the assumptions. The trade that does occur remains mutually voluntary and both traders are better off than they were with no trade. Indeed, Smith is better off than he would be trading with Jones and Kim; he must value friendship more than more goods or else he wouldn’t have voluntarily chosen this. The sole loser from this arrangement is Farmer Kim, who doesn’t get to enjoy the benefits of trade.

Going back to the assumption of profit seeking, however, the example demonstrates a number of important principles. The first point is that free and open competition is not necessarily in the interests of everyone. The arrival of Farmer Kim in the market generates benefits for one of the original traders and losses for the other. We can characterize the winners and losers more generally by noting that each farmer has two roles in the market. Each is a seller of one product and a buyer of another. Farmer Smith is a seller of oranges but a buyer of apples. Farmer Jones and Farmer Kim are sellers of apples but buyers of oranges.

Farmer Kim’s entrance into the market represents an addition to the number of sellers of apples and the number of buyers of oranges. First, consider Farmer Jones’s perspective as a seller of apples. When an additional seller of apples enters the market, Farmer Jones is made worse off. Thus, in a free market, sellers of products are worse off the larger the number of other sellers of similar products. Open competition is simply not in the best interests of the sellers of products. At the extreme, the most preferred position of a seller is to have the market to himself—that is, to have a monopolyAn individual or firm that is the sole seller of a product in a market. position in the market. Monopoly profits are higher than could ever be obtained in a duopoly, in an oligopoly, or with perfect competition.

Next, consider Farmer Smith’s perspective as a buyer of apples. When Farmer Kim enters the market, Farmer Smith has more sources of apples than he had previously. This results in a decrease in the price he must pay and makes him better off. Extrapolating, buyers of a product will prefer to have as many sellers of the products they buy as possible. The very worst position for a buyer is to have a single monopolistic supplier. The best position is to face a perfectly competitive market with lots of individual sellers, where competition may generate lower prices.

Alternatively, consider Farmer Jones’s position as a buyer of oranges. When Farmer Kim enters the market there is an additional buyer. The presence of more buyers makes every original buyer worse off. Thus we can conclude that buyers of products would prefer to have as few other buyers as possible. The best position for a buyer is a monopsonyAn individual or firm that is the sole buyer of a product in a market.—a situation in which he is the single buyer of a product.

Finally, consider Farmer Smith’s role as a seller of oranges. When an additional buyer enters the market, Farmer Smith becomes better off. Thus sellers of products would like to have as many buyers for their product as possible.

More generally, we can conclude that producers of products (sellers) should have little interest in free and open competition in their market, preferring instead to restrict the entry of any potential competitors. However, producers also want as large a market of consumers for their products as possible. Consumers of these products (buyers) should prefer free and open competition with as many producers as possible. However, consumers also want as few other consumers as possible for the products they buy. Note well that the interests of producers and consumers are diametrically opposed. This simple truth means that it will almost assuredly be impossible for any change in economic conditions, arising either out of natural dynamic forces in the economy or as a result of government policies, to be in the best interests of everyone in the country.

Key Takeaways

- Greater competition (more sellers) in a market reduces the price of that good and lowers the well-being of the previous sellers. (Sellers dislike more sellers of the goods they sell.)

- Greater competition (more sellers) in a market raises the price of the buyer’s goods and increases the well-being of the previous buyers. (Buyers like more sellers of the goods they buy.)

- The changes described above assume individuals are profit seeking.

Exercise

-

Consider two farmers, one with an endowment of five pounds of peaches, the other with an endowment of five pounds of cherries. Suppose these two farmers meet daily and make a mutually agreeable exchange of two pounds of peaches for three pounds of cherries.

-

Write down an expression for the terms of trade. Explain how the terms of trade relates to the dollar prices of the two goods.

Consider the following shocks (or changes). Explain how each of these shocks may influence the terms of trade between the farmers. Assume that each farmer’s sole interest is to maximize her own utility.

- The cherry farmer arrives at the market with five extra pounds of cherries.

- The peach farmer has just finished reading a book titled How to Influence People.

- Damp weather causes mold to grow on 40 percent of the peaches.

- News reports indicate that cherry consumption can reduce the risk of cancer.

-