This is “Example of a Trade Pattern”, section 3.3 from the book Policy and Theory of International Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.3 Example of a Trade Pattern

Learning Objective

- Learn how to describe a mutually voluntary exchange pattern and specify both the terms of trade and the final consumption bundles for two traders.

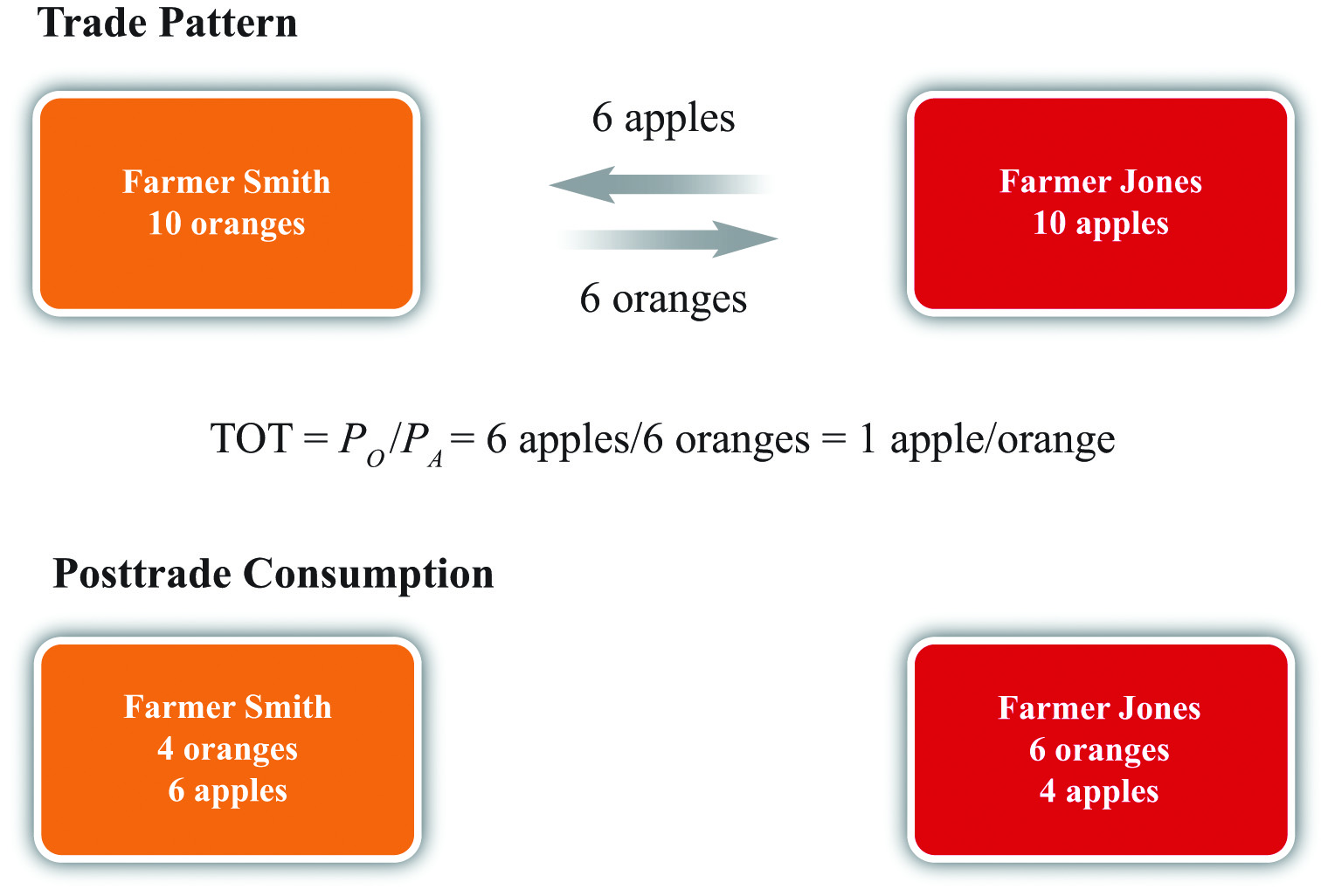

Suppose after some discussion Farmer Smith and Farmer Jones agree to a mutually voluntary exchangeA trade of one item for another chosen willingly (i.e., without coercion) by both individuals in a market. of six apples for six oranges (see Figure 3.1 "Two-Farmer Trade Pattern"). The terms of trade is six apples per six oranges, or one apple per orange. After trade, Farmer Smith will have four oranges and six apples to consume, while Farmer Jones will have six oranges and four apples to consume. As long as the trade is voluntary, it must hold that both farmers expect to be better off after trade since they are free not to trade. Thus mutually voluntary trade must be beneficial for both farmers.

Figure 3.1 Two-Farmer Trade Pattern

Sometimes people talk about trade as if it were adversarial, with one side competing against the other. With this impression, one might believe that trade would generate a winner and a loser as if trade were a contest. However, a pure exchange model demonstrates that trade is not a zero-sum game. Instead, when two individuals make a voluntary exchange, they will both benefit. This is sometimes calls a positive-sum game.A zero-sum game is a contest whose outcome involves gains and losses of equal value so that the sum of the gains and losses is zero. In contrast, a positive-sum game is one whose outcome involves total gains that exceed the total losses so that the sum of the gains and losses is positive.

Sometimes the pure exchange model is placed in the context of two trading countries. Suppose instead of Farmer Smith and Farmer Jones, we imagine the United States and Canada as the two “individuals” who trade with each other. Or, better still, we might recognize that international trade between countries consists of millions, or billions, of individual trades much like the one described here. If each individual trade is mutually advantageous, then the summation of billions of such trades must also be mutually advantageous. Thus, as long as the people within each country can choose not to trade if they so desire, trade must be beneficial for every trader in both countries.

Nonetheless, although this conclusion is sound, it is incorrect to assert that everyone in each country will necessarily benefit from free trade. Although the national effects will be positive, a country is composed of many individuals, many of whom do not engage in international trade. Trade can make some of them worse off. In other words, trade is likely to cause a redistribution of income, generating both winners and losers. This outcome is first shown in Chapter 3 "The Pure Exchange Model of Trade", Section 3.4 "Three Traders and Redistribution with Trade".

Key Takeaways

- Any trade pattern between individuals may be claimed to be mutually advantageous as long as the trade is mutually voluntary.

- The terms of trade is defined as the ratio of the trade quantities of the two goods.

- The final consumption bundles are found by subtracting what one gives away and adding what one receives to one’s original endowment.

Exercise

-

Suppose Kendra has ten pints of milk and five cookies and Thomas has fifty cookies and one pint of milk.

- Specify a plausible mutually advantageous trading pattern.

- Identify the terms of trade in your example (use units of pints per cookie).

- Identify the final consumption bundles for Kendra and Thomas.

- Which assumption or assumptions guarantee that the final consumption bundles provide greater utility than the initial endowments for both Kendra and Thomas?