This is “The Concept of Utility”, section 7.1 from the book Microeconomics Principles (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.1 The Concept of Utility

Learning Objectives

- Define what economists mean by utility.

- Distinguish between the concepts of total utility and marginal utility.

- State the law of diminishing marginal utility and illustrate it graphically.

- State, explain, and illustrate algebraically the utility-maximizing condition.

Why do you buy the goods and services you do? It must be because they provide you with satisfaction—you feel better off because you have purchased them. Economists call this satisfaction utility.

The concept of utility is an elusive one. A person who consumes a good such as peaches gains utility from eating the peaches. But we cannot measure this utility the same way we can measure a peach’s weight or calorie content. There is no scale we can use to determine the quantity of utility a peach generates.

Francis Edgeworth, one of the most important contributors to the theory of consumer behavior, imagined a device he called a hedonimeter (after hedonism, the pursuit of pleasure):

“[L]et there be granted to the science of pleasure what is granted to the science of energy; to imagine an ideally perfect instrument, a psychophysical machine, continually registering the height of pleasure experienced by an individual…. From moment to moment the hedonimeter varies; the delicate index now flickering with the flutter of passions, now steadied by intellectual activity, now sunk whole hours in the neighborhood of zero, or momentarily springing up towards infinity.”Francis Y. Edgeworth, Mathematical Psychics: An Essay on the Application of Mathematics to the Moral Sciences (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1967), p. 101. First Published 1881.

Perhaps some day a hedonimeter will be invented. The utility it measures will not be a characteristic of particular goods, but rather of each consumer’s reactions to those goods. The utility of a peach exists not in the peach itself, but in the preferences of the individual consuming the peach. One consumer may wax ecstatic about a peach; another may say it tastes OK.

When we speak of maximizing utility, then, we are speaking of the maximization of something we cannot measure. We assume, however, that each consumer acts as if he or she can measure utility and arranges consumption so that the utility gained is as high as possible.

Total Utility

If we could measure utility, total utilityThe number of units of utility that a consumer gains from consuming a given quantity of a good, service, or activity during a particular time period. would be the number of units of utility that a consumer gains from consuming a given quantity of a good, service, or activity during a particular time period. The higher a consumer’s total utility, the greater that consumer’s level of satisfaction.

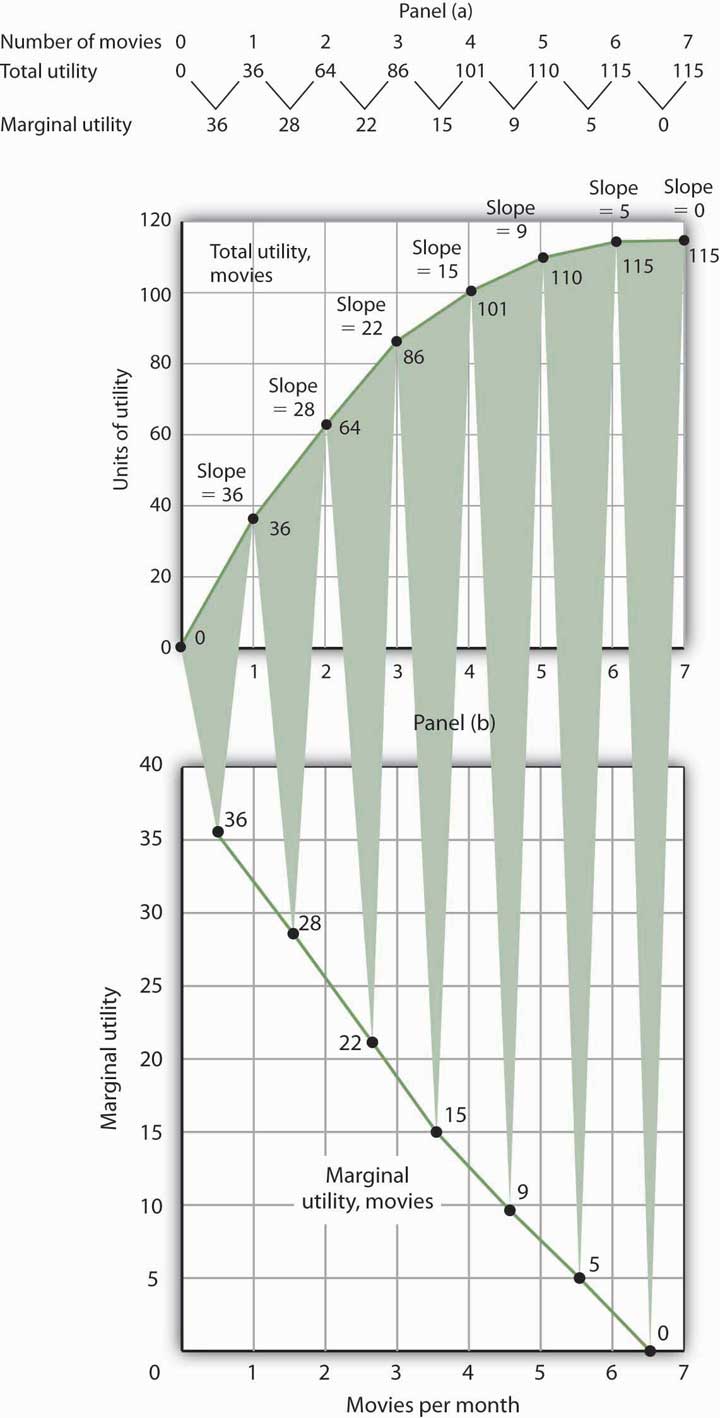

Panel (a) of Figure 7.1 "Total Utility and Marginal Utility Curves" shows the total utility Henry Higgins obtains from attending movies. In drawing his total utility curve, we are imagining that he can measure his total utility. The total utility curve shows that when Mr. Higgins attends no movies during a month, his total utility from attending movies is zero. As he increases the number of movies he sees, his total utility rises. When he consumes 1 movie, he obtains 36 units of utility. When he consumes 4 movies, his total utility is 101. He achieves the maximum level of utility possible, 115, by seeing 6 movies per month. Seeing a seventh movie adds nothing to his total utility.

Figure 7.1 Total Utility and Marginal Utility Curves

Panel (a) shows Henry Higgins’s total utility curve for attending movies. It rises as the number of movies increases, reaching a maximum of 115 units of utility at 6 movies per month. Marginal utility is shown in Panel (b); it is the slope of the total utility curve. Because the slope of the total utility curve declines as the number of movies increases, the marginal utility curve is downward sloping.

Mr. Higgins’s total utility rises at a decreasing rate. The rate of increase is given by the slope of the total utility curve, which is reported in Panel (a) of Figure 7.1 "Total Utility and Marginal Utility Curves" as well. The slope of the curve between 0 movies and 1 movie is 36 because utility rises by this amount when Mr. Higgins sees his first movie in the month. It is 28 between 1 and 2 movies, 22 between 2 and 3, and so on. The slope between 6 and 7 movies is zero; the total utility curve between these two quantities is horizontal.

Marginal Utility

The amount by which total utility rises with consumption of an additional unit of a good, service, or activity, all other things unchanged, is marginal utilityThe amount by which total utility rises with consumption of an additional unit of a good, service, or activity, all other things unchanged.. The first movie Mr. Higgins sees increases his total utility by 36 units. Hence, the marginal utility of the first movie is 36. The second increases his total utility by 28 units; its marginal utility is 28. The seventh movie does not increase his total utility; its marginal utility is zero. Notice that in the table marginal utility is listed between the columns for total utility because, similar to other marginal concepts, marginal utility is the change in utility as we go from one quantity to the next. Mr. Higgins’s marginal utility curve is plotted in Panel (b) of Figure 7.1 "Total Utility and Marginal Utility Curves" The values for marginal utility are plotted midway between the numbers of movies attended. The marginal utility curve is downward sloping; it shows that Mr. Higgins’s marginal utility for movies declines as he consumes more of them.

Mr. Higgins’s marginal utility from movies is typical of all goods and services. Suppose that you are really thirsty and you decide to consume a soft drink. Consuming the drink increases your utility, probably by a lot. Suppose now you have another. That second drink probably increases your utility by less than the first. A third would increase your utility by still less. This tendency of marginal utility to decline beyond some level of consumption during a period is called the law of diminishing marginal utilityThis tendency of marginal utility to decline beyond some level of consumption during a period.. This law implies that all goods and services eventually will have downward-sloping marginal utility curves. It is the law that lies behind the negatively sloped marginal benefit curve for consumer choices that we examined in the chapter on markets, maximizers, and efficiency.

One way to think about this effect is to remember the last time you ate at an “all you can eat” cafeteria-style restaurant. Did you eat only one type of food? Did you consume food without limit? No, because of the law of diminishing marginal utility. As you consumed more of one kind of food, its marginal utility fell. You reached a point at which the marginal utility of another dish was greater, and you switched to that. Eventually, there was no food whose marginal utility was great enough to make it worth eating, and you stopped.

What if the law of diminishing marginal utility did not hold? That is, what would life be like in a world of constant or increasing marginal utility? In your mind go back to the cafeteria and imagine that you have rather unusual preferences: Your favorite food is creamed spinach. You start with that because its marginal utility is highest of all the choices before you in the cafeteria. As you eat more, however, its marginal utility does not fall; it remains higher than the marginal utility of any other option. Unless eating more creamed spinach somehow increases your marginal utility for some other food, you will eat only creamed spinach. And until you have reached the limit of your body’s capacity (or the restaurant manager’s patience), you will not stop. Failure of marginal utility to diminish would thus lead to extraordinary levels of consumption of a single good to the exclusion of all others. Since we do not observe that happening, it seems reasonable to assume that marginal utility falls beyond some level of consumption.

Maximizing Utility

Economists assume that consumers behave in a manner consistent with the maximization of utility. To see how consumers do that, we will put the marginal decision rule to work. First, however, we must reckon with the fact that the ability of consumers to purchase goods and services is limited by their budgets.

The Budget Constraint

The total utility curve in Figure 7.1 "Total Utility and Marginal Utility Curves" shows that Mr. Higgins achieves the maximum total utility possible from movies when he sees six of them each month. It is likely that his total utility curves for other goods and services will have much the same shape, reaching a maximum at some level of consumption. We assume that the goal of each consumer is to maximize total utility. Does that mean a person will consume each good at a level that yields the maximum utility possible?

The answer, in general, is no. Our consumption choices are constrained by the income available to us and by the prices we must pay. Suppose, for example, that Mr. Higgins can spend just $25 per month for entertainment and that the price of going to see a movie is $5. To achieve the maximum total utility from movies, Mr. Higgins would have to exceed his entertainment budget. Since we assume that he cannot do that, Mr. Higgins must arrange his consumption so that his total expenditures do not exceed his budget constraintA restriction that total spending cannot exceed the budget available.: a restriction that total spending cannot exceed the budget available.

Suppose that in addition to movies, Mr. Higgins enjoys concerts, and the average price of a concert ticket is $10. He must select the number of movies he sees and concerts he attends so that his monthly spending on the two goods does not exceed his budget.

Individuals may, of course, choose to save or to borrow. When we allow this possibility, we consider the budget constraint not just for a single period of time but for several periods. For example, economists often examine budget constraints over a consumer’s lifetime. A consumer may in some years save for future consumption and in other years borrow on future income for present consumption. Whatever the time period, a consumer’s spending will be constrained by his or her budget.

To simplify our analysis, we shall assume that a consumer’s spending in any one period is based on the budget available in that period. In this analysis consumers neither save nor borrow. We could extend the analysis to cover several periods and generate the same basic results that we shall establish using a single period. We will also carry out our analysis by looking at the consumer’s choices about buying only two goods. Again, the analysis could be extended to cover more goods and the basic results would still hold.

Applying the Marginal Decision Rule

Because consumers can be expected to spend the budget they have, utility maximization is a matter of arranging that spending to achieve the highest total utility possible. If a consumer decides to spend more on one good, he or she must spend less on another in order to satisfy the budget constraint.

The marginal decision rule states that an activity should be expanded if its marginal benefit exceeds its marginal cost. The marginal benefit of this activity is the utility gained by spending an additional $1 on the good. The marginal cost is the utility lost by spending $1 less on another good.

How much utility is gained by spending another $1 on a good? It is the marginal utility of the good divided by its price. The utility gained by spending an additional dollar on good X, for example, is

This additional utility is the marginal benefit of spending another $1 on the good.

Suppose that the marginal utility of good X is 4 and that its price is $2. Then an extra $1 spent on X buys 2 additional units of utility ( ). If the marginal utility of good X is 1 and its price is $2, then an extra $1 spent on X buys 0.5 additional units of utility ( ).

The loss in utility from spending $1 less on another good or service is calculated the same way: as the marginal utility divided by the price. The marginal cost to the consumer of spending $1 less on a good is the loss of the additional utility that could have been gained from spending that $1 on the good.

Suppose a consumer derives more utility by spending an additional $1 on good X rather than on good Y:

Equation 7.1

The marginal benefit of shifting $1 from good Y to the consumption of good X exceeds the marginal cost. In terms of utility, the gain from spending an additional $1 on good X exceeds the loss in utility from spending $1 less on good Y. The consumer can increase utility by shifting spending from Y to X.

As the consumer buys more of good X and less of good Y, however, the marginal utilities of the two goods will change. The law of diminishing marginal utility tells us that the marginal utility of good X will fall as the consumer consumes more of it; the marginal utility of good Y will rise as the consumer consumes less of it. The result is that the value of the left-hand side of Equation 7.1 will fall and the value of the right-hand side will rise as the consumer shifts spending from Y to X. When the two sides are equal, total utility will be maximized. In terms of the marginal decision rule, the consumer will have achieved a solution at which the marginal benefit of the activity (spending more on good X) is equal to the marginal cost:

Equation 7.2

We can extend this result to all goods and services a consumer uses. Utility maximization requires that the ratio of marginal utility to price be equal for all of them, as suggested in Equation 7.3:

Equation 7.3

Equation 7.3 states the utility-maximizing conditionUtility is maximized when total outlays equal the budget available and when the ratios of marginal utilities to prices are equal for all goods and services.: Utility is maximized when total outlays equal the budget available and when the ratios of marginal utilities to prices are equal for all goods and services.

Consider, for example, the shopper introduced in the opening of this chapter. In shifting from cookies to ice cream, the shopper must have felt that the marginal utility of spending an additional dollar on ice cream exceeded the marginal utility of spending an additional dollar on cookies. In terms of Equation 7.1, if good X is ice cream and good Y is cookies, the shopper will have lowered the value of the left-hand side of the equation and moved toward the utility-maximizing condition, as expressed by Equation 7.1.

The Problem of Divisibility

If we are to apply the marginal decision rule to utility maximization, goods must be divisible; that is, it must be possible to buy them in any amount. Otherwise we cannot meaningfully speak of spending $1 more or $1 less on them. Strictly speaking, however, few goods are completely divisible.

Even a small purchase, such as an ice cream bar, fails the strict test of being divisible; grocers generally frown on requests to purchase one-half of a $2 ice cream bar if the consumer wants to spend an additional dollar on ice cream. Can a consumer buy a little more movie admission, to say nothing of a little more car?

In the case of a car, we can think of the quantity as depending on characteristics of the car itself. A car with a compact disc player could be regarded as containing “more car” than one that has only a cassette player. Stretching the concept of quantity in this manner does not entirely solve the problem. It is still difficult to imagine that one could purchase “more car” by spending $1 more.

Remember, though, that we are dealing with a model. In the real world, consumers may not be able to satisfy Equation 7.3 precisely. The model predicts, however, that they will come as close to doing so as possible.

Key Takeaways

- The utility of a good or service is determined by how much satisfaction a particular consumer obtains from it. Utility is not a quality inherent in the good or service itself.

- Total utility is a conceptual measure of the number of units of utility a consumer gains from consuming a good, service, or activity. Marginal utility is the increase in total utility obtained by consuming one more unit of a good, service, or activity.

- As a consumer consumes more and more of a good or service, its marginal utility falls.

- Utility maximization requires seeking the greatest total utility from a given budget.

- Utility is maximized when total outlays equal the budget available and when the ratios of marginal utility to price are equal for all goods and services a consumer consumes; this is the utility-maximizing condition.

Try It!

A college student, Ramón Juárez, often purchases candy bars or bags of potato chips between classes; he tries to limit his spending on these snacks to $8 per week. A bag of chips costs $0.75 and a candy bar costs $0.50 from the vending machines on campus. He has been purchasing an average of 6 bags of chips and 7 candy bars each week. Mr. Juárez is a careful maximizer of utility, and he estimates that the marginal utility of an additional bag of chips during a week is 6. In your answers use B to denote candy bars and C to denote potato chips.

- How much is he spending on snacks? How does this amount compare to his budget constraint?

- What is the marginal utility of an additional candy bar during the week?

Case in Point: Changing Lanes and Raising Utility

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

In preparation for sitting in the slow, crowded lanes for single-occupancy-vehicles, T. J. Zane used to stop at his favorite coffee kiosk to buy a $2 cup of coffee as he headed off to work on Interstate 15 in the San Diego area. Since 1996, an experiment in road pricing has caused him and others to change their ways—and to raise their total utility.

Before 1996, only car-poolers could use the specially marked high-occupancy-vehicles lanes. With those lanes nearly empty, traffic authorities decided to allow drivers of single-occupancy-vehicles to use those lanes, so long as they paid a price. Now, electronic signs tell drivers how much it will cost them to drive on the special lanes. The price is recalculated every 6 minutes depending on the traffic. On one morning during rush hour, it varied from $1.25 at 7:10 a.m., to $1.50 at 7:16 a.m., to $2.25 at 7:22 a.m., and to $2.50 at 7:28 a.m. The increasing tolls over those few minutes caused some drivers to opt out and the toll fell back to $1.75 and then increased to $2 a few minutes later. Drivers do not have to stop to pay the toll since radio transmitters read their FasTrak transponders and charge them accordingly.

When first instituted, these lanes were nicknamed the “Lexus lanes,” on the assumption that only wealthy drivers would use them. Indeed, while the more affluent do tend to use them heavily, surveys have discovered that they are actually used by drivers of all income levels.

Mr. Zane, a driver of a 1997 Volkswagen Jetta, is one commuter who chooses to use the new option. He explains his decision by asking, “Isn’t it worth a couple of dollars to spend an extra half-hour with your family?” He continues, “That’s what I used to spend on a cup of coffee at Starbucks. Now I’ve started bringing my own coffee and using the money for the toll.”

We can explain his decision using the model of utility-maximizing behavior; Mr. Zane’s out-of-pocket commuting budget constraint is about $2. His comment tells us that he realized that the marginal utility of spending an additional 30 minutes with his family divided by the $2 toll was higher than the marginal utility of the store-bought coffee divided by its $2 price. By reallocating his $2 commuting budget, the gain in utility of having more time at home exceeds the loss in utility from not sipping premium coffee on the way to work.

From this one change in behavior, we do not know whether or not he is actually maximizing his utility, but his decision and explanation are certainly consistent with that goal.

Source: John Tierney, “The Autonomist Manifesto (Or, How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Road),” New York Times Magazine, September 26, 2004, 57–65.

Answers to Try It! Problems

- He is spending $4.50 (= $0.75 × 6) on potato chips and $3.50 (= $0.50 × 7) on candy bars, for a total of $8. His budget constraint is $8.

-

In order for the ratios of marginal utility to price to be equal, the marginal utility of a candy bar must be 4. Let the marginal utility and price of candy bars be MUB and PB, respectively, and the marginal utility and price of a bag of potato chips be MUC and PC, respectively. Then we want

We know that PC is $0.75 and PB equals $0.50. We are told that MUC is 6. Thus

Solving the equation for MUB, we find that it must equal 4.