This is “Assets”, section 2.2 from the book Individual Finance (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

2.2 Assets

Learning Objectives

- Identify the purposes and uses of assets.

- Identify the types of assets.

- Explain the role of assets in personal finance.

- Explain how a capital gain or loss is created.

As defined earlier in this chapter, an asset is any item with economic value that can be converted to cash. Assets are resources that can be used to create income or reduce expenses and to store value. The following are examples of tangible (material) assets:

- Car

- Savings account

- Wind-up toy collection

- Money market account

- Shares of stock

- Forty acres of farmland

- Home

When you sell excess capital in the capital markets in exchange for an asset, it is a way of storing wealth, and hopefully of generating income as well. The asset is your investment—a use of your liquidity. Some assets are more liquid than others. For example, you can probably sell your car more quickly than you can sell your house. As an investor, you assume that when you want your liquidity back, you can sell the asset. This assumes that it has some liquidity and market value (some use and value to someone else) and that it trades in a reasonably efficient market. Otherwise, the asset is not an investment, but merely a possession, which may bring great happiness but will not serve as a store of wealth.

Assets may be used to store wealth, create income, and reduce future expenses.

Assets Store Wealth

Figure 2.6

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

If the asset is worth more when it is resold than it was when it was bought, then you have earned a capital gainWealth created when an asset is sold for more than the original investment.: the investment has not only stored wealth but also increased it. Of course, things can go the other way too: the investment can decrease in value while owned and be worth less when resold than it was when bought. In that case, you have a capital lossWealth lost when an asset is sold for less than the original investment.. The investment not only did not store wealth, it lost some. Figure 2.7 "Gains and Losses" shows how capital gains and losses are created.

Figure 2.7 Gains and Losses

The better investment asset is the one that increases in value—creates a capital gain—during the time you are storing it.

Assets Create Income

Some assets not only store wealth but also create income. An investment in an apartment house stores wealth and creates rental income, for example. An investment in a share of stock stores wealth and also perhaps creates dividend income. A deposit in a savings account stores wealth and creates interest income.

Some investors care more about increasing asset value than about income. For example, an investment in a share of corporate stock may produce a dividend, which is a share of the corporation’s profit, or the company may keep all its profit rather than pay dividends to shareholders. Reinvesting that profit in the company may help the company to increase in value. If the company increases in value, the stock increases in value, increasing investors’ wealth. Further, increases in wealth through capital gains are taxed differently than income, making capital gains more valuable than an increase in income for some investors.

On the other hand, other investors care more about receiving income from their investments. For example, retirees who no longer have employment income may be relying on investments to provide income for living expenses. Being older and having a shorter horizon, retirees may be less concerned with growing wealth than with creating income.

Assets Reduce Expenses

Some assets are used to reduce living expenses. Purchasing an asset and using it may be cheaper than arranging for an alternative. For example, buying a car to drive to work may be cheaper, in the long run, than renting one or using public transportation. The car typically will not increase in value, so it cannot be expected to be a store of wealth; its only role is to reduce future expenses.

Sometimes an asset may be expected to both store wealth and reduce future expenses. For example, buying a house to live in may be cheaper, in the long run, than renting one. In addition, real estate may appreciate in value, allowing you to realize a gain when you sell the asset. In this case, the house has effectively stored wealth. Appreciation in value depends on the real estate market and demand for housing when the asset is sold, however, so you cannot count on it. Still, a house usually can reduce living expenses and be a potential store of wealth.

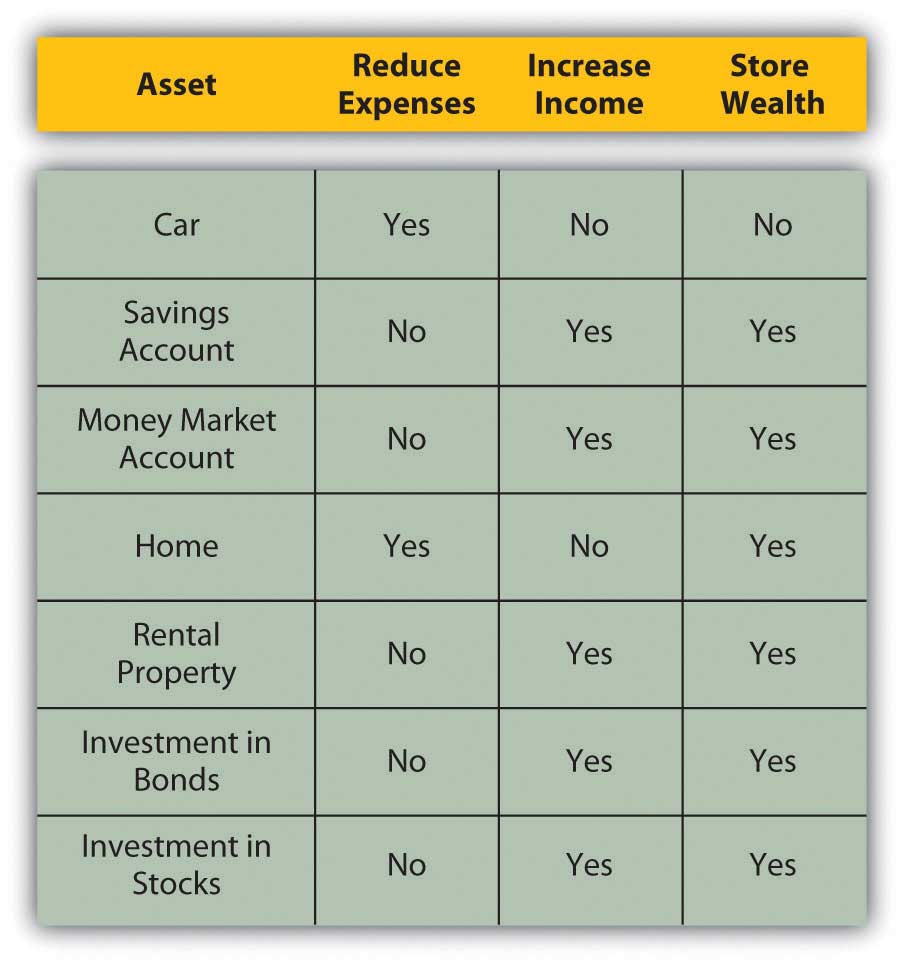

Figure 2.8 "Assets and the Roles of Assets" shows the roles of assets in reducing expenses, increasing income, and storing wealth.

Figure 2.8 Assets and the Roles of Assets

The choice of investment asset, then, depends on your belief in its ability to store and increase wealth, create income, or reduce expenses. Ideally, your assets will store and increase wealth while increasing income or reducing expenses. Otherwise, acquiring the asset will not be a productive use of liquidity. Also, in that case the opportunity cost will be greater than the benefit from the investment, since there are many assets to choose from.

Key Takeaways

- Assets are items with economic value that can be converted to cash. You use excess liquidity or surplus cash to buy an asset and store wealth until you resell the asset.

- An asset can create income, reduce expenses, and store wealth.

- To have value as an investment, an asset must either store wealth or create income (reduce expenses); ideally, an asset can do both.

- Whatever the type of asset you choose, investing in assets or selling capital can be more profitable than selling labor.

- Selling an asset can result in a capital gain or capital loss.

- Selling capital means trading in the capital markets, which is a sellers’ market. You can do this only if you have a budget surplus, or an excess of income over expenses.

Exercises

- Record your answers to the following questions in your personal finance journal or My Notes. What are your assets? How do your assets store your wealth? How do your assets make income for you? How do your assets help you reduce your expenses?

- List your assets in the order of their cash or market value (most valuable to least valuable). Then list them in terms of their degree of liquidity. Which assets do you think you might sell in the next ten years? Why? What new assets do you think you would like to acquire and why? How could you reorganize your budget to make it possible to invest in new assets?