This is “Effective Business Writing”, chapter 9 from the book English for Business Success (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 9 Effective Business Writing

However great…natural talent may be, the art of writing cannot be learned all at once.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Read, read, read…Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master.

William Faulkner

You only learn to be a better writer by actually writing.

Doris Lessing

Getting Started

Introductory Exercises

- Take a moment to write three words that describe your success in writing.

- Make a list of words that you associate with writing. Compare your list with those of your classmates.

- Briefly describe your experience writing and include one link to something you like to read in your post.

Something we often hear in business is, “Get it in writing.” This advice is meant to prevent misunderstandings based on what one person thought the other person said. But does written communication—getting it in writing—always prevent misunderstandings?

According to a Washington Post news story, a written agreement would have been helpful to an airline customer named Mike. A victim of an airport mishap, Mike was given vouchers for $7,500 worth of free travel. However, in accordance with the airline’s standard policy, the vouchers were due to expire in twelve months. When Mike saw that he and his wife would not be able to do enough flying to use the entire amount before the expiration date, he called the airline and asked for an extension. He was told the airline would extend the deadline, but later discovered they were willing to do so at only 50 percent of the vouchers’ value. An airline spokesman told the newspaper, “If [Mike] can produce a letter stating that we would give the full value of the vouchers, he should produce it.”Oldenburg, D. (2005, April 12). Old adage holds: Get it in writing. Washington Post, p. C10. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A45309-2005Apr11.html

Yet, as we will see in this chapter, putting something in writing is not always a foolproof way to ensure accuracy and understanding. A written communication is only as accurate as the writer’s knowledge of the subject and audience, and understanding depends on how well the writer captures the reader’s attention.

This chapter addresses the written word in a business context. We will also briefly consider the symbols, design, font, timing, and related nonverbal expressions you make when composing a page or document. Our discussions will focus on effective communication of your thoughts and ideas through writing that is clear, concise, and efficient.

9.1 Oral versus Written Communication

Learning Objective

- Explain how written communication is similar to oral communication, and how it is different.

The written word often stands in place of the spoken word. People often say “it was good to hear from you” when they receive an e-mail or a letter, when in fact they didn’t hear the message, they read it. Still, if they know you well, they may mentally “hear” your voice in your written words. Writing a message to friends or colleagues can be as natural as talking to them. Yet when we are asked to write something, we often feel anxious and view writing as a more effortful, exacting process than talking would be.

Oral and written forms of communication are similar in many ways. They both rely on the basic communication process, which consists of eight essential elements: source, receiver, message, channel, receiver, feedback, environment, context, and interference. Table 9.1 "Eight Essential Elements of Communication" summarizes these elements and provides examples of how each element might be applied in oral and written communication.

Table 9.1 Eight Essential Elements of Communication

| Element of Communication | Definition | Oral Application | Written Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Source | A source creates and communicates a message. | Jay makes a telephone call to Heather. | Jay writes an e-mail to Heather. |

| 2. Receiver | A receiver receives the message from the source. | Heather listens to Jay. | Heather reads Jay’s e-mail. |

| 3. Message | The message is the stimulus or meaning produced by the source for the receiver. | Jay asks Heather to participate in a conference call at 3:15. | Jay’s e-mail asks Heather to participate in a conference call at 3:15. |

| 4. Channel | A channel is the way a message travels between source and receiver. | The channel is the telephone. | The channel is e-mail. |

| 5. Feedback | Feedback is the message the receiver sends in response to the source. | Heather says yes. | Heather replies with an e-mail saying yes. |

| 6. Environment | The environment is the physical atmosphere where the communication occurs. | Heather is traveling by train on a business trip when she receives Jay’s phone call. | Heather is at her desk when she receives Jay’s e-mail. |

| 7. Context | The context involves the psychological expectations of the source and receiver. | Heather expects Jay to send an e-mail with the call-in information for the call. Jay expects to do so, and does. | Heather expects Jay to dial and connect the call. Jay expects Heather to check her e-mail for the call-in information so that she can join the call. |

| 8. Interference | Also known as noise, interference is anything that blocks or distorts the communication process. | Heather calls in at 3:15, but she has missed the call because she forgot that she is in a different time zone from Jay. | Heather waits for a phone call from Jay at 3:15, but he doesn’t call. |

As you can see from the applications in this example, at least two different kinds of interference have the potential to ruin a conference call, and the interference can exist regardless of whether the communication to plan the call is oral or written. Try switching the “Context” and “Interference” examples from Oral to Written, and you will see that mismatched expectations and time zone confusion can happen by phone or by e-mail. While this example has an unfavorable outcome, it points out a way in which oral and written communication processes are similar.

Another way in which oral and written forms of communication are similar is that they can be divided into verbal and nonverbal categories. Verbal communication involves the words you say, and nonverbal communication involves how you say them—your tone of voice, your facial expression, body language, and so forth. Written communication also involves verbal and nonverbal dimensions. The words you choose are the verbal dimension. How you portray or display them is the nonverbal dimension, which can include the medium (e-mail or a printed document), the typeface or font, or the appearance of your signature on a letter. In this sense, oral and written communication are similar in their approach even as they are quite different in their application.

The written word allows for a dynamic communication process between source and receiver, but is often asynchronousOccurring at different times., meaning that it occurs at different times. When we communicate face-to-face, we get immediate feedback, but our written words stand in place of that interpersonal interaction and we lack that immediate response. Since we are often not physically present when someone reads what we have written, it is important that we anticipate the reader’s needs, interpretation, and likely response to our written messages.

Suppose you are asked to write a message telling clients about a new product or service your company is about to offer. If you were speaking to one of them in a relaxed setting over coffee, what would you say? What words would you choose to describe the product or service, and how it may fulfill the client’s needs? As the business communicator, you must focus on the words you use and how you use them. Short, simple sentences, in themselves composed of words, also communicate a business style. In your previous English classes you may have learned to write eloquently, but in a business context, your goal is clear, direct communication. One strategy to achieve this goal is to write with the same words and phrases you use when you talk. However, since written communication lacks the immediate feedback that is present in an oral conversation, you need to choose words and phrases even more carefully to promote accuracy, clarity, and understanding.

Key Takeaway

Written communication involves the same eight basic elements as oral communication, but it is often asynchronous.

Exercises

- Review the oral and written applications in Table 9.1 "Eight Essential Elements of Communication" and construct a different scenario for each. What could Jay and Heather do differently to make the conference call a success?

- Visit a business Web site that has an “About Us” page. Read the “About Us” message and write a summary in your own words of what it tells you about the company. Compare your results with those of your classmates.

- You are your own company. What words describe you? Design a logo, create a name, and present your descriptive words in a way that gets attention. Share and compare with classmates.

9.2 How Is Writing Learned?

Learning Objective

- Explain how reading, writing, and critical thinking contribute to becoming a good writer.

You may think that some people are simply born better writers than others, but in fact writing is a reflection of experience and effort. If you think about your successes as a writer, you may come up with a couple of favorite books, authors, or teachers that inspired you to express yourself. You may also recall a sense of frustration with your previous writing experiences. It is normal and natural to experience a sense of frustration at the perceived inability to express oneself. The emphasis here is on your perception of yourself as a writer as one aspect of how you communicate. Most people use oral communication for much of their self-expression, from daily interactions to formal business meetings. You have a lifetime of experience in that arena that you can leverage to your benefit in your writing. Reading out loud what you have written is a positive technique we’ll address later in more depth.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s statement, “Violence is the language of the unheard” emphasizes the importance of finding one’s voice, of being able to express one’s ideas. Violence comes in many forms, but is often associated with frustration born of the lack of opportunity to communicate. You may read King’s words and think of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, or perhaps of the violence of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, or of wars happening in the world today. Public demonstrations and fighting are expressions of voice, from individual to collective. Finding your voice, and learning to listen to others, is part of learning to communicate.

You are your own best ally when it comes to your writing. Keeping a positive frame of mind about your journey as a writer is not a cliché or simple, hollow advice. Your attitude toward writing can and does influence your written products. Even if writing has been a challenge for you, the fact that you are reading this sentence means you perceive the importance of this essential skill. This text and our discussions will help you improve your writing, and your positive attitude is part of your success strategy.

There is no underestimating the power of effort when combined with inspiration and motivation. The catch then is to get inspired and motivated. That’s not all it takes, but it is a great place to start. You were not born with a key pad in front of you, but when you want to share something with friends and text them, the words (or abbreviations) come almost naturally. So you recognize you have the skills necessary to begin the process of improving and harnessing your writing abilities for business success. It will take time and effort, and the proverbial journey starts with a single step, but don’t lose sight of the fact that your skillful ability to craft words will make a significant difference in your career.

Reading

Reading is one step many writers point to as an integral step in learning to write effectively. You may like Harry Potter books or be a Twilight fan, but if you want to write effectively in business, you need to read business-related documents. These can include letters, reports, business proposals, and business plans. You may find these where you work or in your school’s writing center, business department, or library; there are also many Web sites that provide sample business documents of all kinds. Your reading should also include publications in the industry where you work or plan to work, such as Aviation Week, InfoWorld, Journal of Hospitality, International Real Estate Digest, or Women’s Wear Daily, to name just a few. You can also gain an advantage by reading publications in fields other than your chosen one; often reading outside your niche can enhance your versatility and help you learn how other people express similar concepts. Finally, don’t neglect general media like the business section of your local newspaper, and national publications like the Wall Street Journal, Fast Company, and the Harvard Business Review. Reading is one of the most useful lifelong habits you can practice to boost your business communication skills.

Figure 9.1

Reading is one of the most useful lifelong habits you can practice to boost your business communication skills.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

In the “real world” when you are under a deadline and production is paramount, you’ll be rushed and may lack the time to do adequate background reading for a particular assignment. For now, take advantage of your business communication course by exploring common business documents you may be called on to write, contribute to, or play a role in drafting. Some documents have a degree of formula to them, and your familiarity with them will reduce your preparation and production time while increasing your effectiveness. As you read similar documents, take notes on what you observe. As you read several sales letters, you may observe several patterns that can serve you well later on when it’s your turn. These patterns are often called conventionsConventional language patterns for a specific genre., or conventional language patterns for a specific genre.

Writing

Never lose sight of one key measure of the effectiveness of your writing: the degree to which it fulfills readers’ expectations. If you are in a law office, you know the purpose of a court brief is to convince the judge that certain points of law apply to the given case. If you are at a newspaper, you know that an editorial opinion article is supposed to convince readers of the merits of a certain viewpoint, whereas a news article is supposed to report facts without bias. If you are writing ad copy, the goal is to motivate consumers to make a purchase decision. In each case, you are writing to a specific purpose, and a great place to start when considering what to write is to answer the following question: what are the readers’ expectations?

When you are a junior member of the team, you may be given clerical tasks like filling in forms, populating a database, or coordinating appointments. Or you may be assigned to do research that involves reading, interviewing, and note taking. Don’t underestimate these facets of the writing process; instead, embrace the fact that writing for business often involves tasks that a novelist might not even recognize as “writing.” Your contribution is quite important and in itself is an on-the-job learning opportunity that shouldn’t be taken for granted.

When given a writing assignment, it is important to make sure you understand what you are being asked to do. You may read the directions and try to put them in your own words to make sense of the assignment. Be careful, however, not to lose sight of what the directions say versus what you think they say. Just as an audience’s expectations should be part of your consideration of how, what, and why to write, the instructions given by your instructor, or in a work situation by your supervisor, establish expectations. Just as you might ask a mentor more about a business writing assignment at work, you need to use the resources available to you to maximize your learning opportunity. Ask the professor to clarify any points you find confusing, or perceive more than one way to interpret, in order to better meet the expectations.

Before you write an opening paragraph, or even the first sentence, it is important to consider the overall goal of the assignment. The word assignment can apply equally to a written product for class or for your employer. You might make a list of the main points and see how those points may become the topic sentences in a series of paragraphs. You may also give considerable thought to whether your word choice, your tone, your language, and what you want to say is in line with your understanding of your audience. We briefly introduced the writing process previously, and will visit it in depth later in our discussion, but for now writing should about exploring your options. Authors rarely have a finished product in mind when they start, but once you know what your goal is and how to reach it, you writing process will become easier and more effective.

Constructive Criticism and Targeted Practice

Mentors can also be important in your growth as a writer. Your instructor can serve as a mentor, offering constructive criticism, insights on what he or she has written, and life lessons about writing for a purpose. Never underestimate the mentors that surround you in the workplace, even if you are currently working in a position unrelated to your desired career. They can read your rough draft and spot errors, as well as provide useful insights. Friends and family can also be helpful mentors—if your document’s meaning is clear to someone not working in your business, it will likely also be clear to your audience.

The key is to be open to criticism, keeping in mind that no one ever improved by repeating bad habits over and over. Only when you know what your errors are—errors of grammar or sentence structure, logic, format, and so on—can you correct your document and do a better job next time. Writing can be a solitary activity, but more often in business settings it is a collective, group, or team effort. Keep your eyes and ears open for opportunities to seek outside assistance before you finalize your document.

Learning to be a successful business writer comes with practice. Targeted practiceIdentifying one’s weak areas and specifically working to improve them., which involves identifying your weak areas and specifically working to improve them, is especially valuable. In addition to reading, make it a habit to write, even if it is not a specific assignment. The more you practice writing the kinds of materials that are used in your line of work, the more writing will come naturally and become an easier task—even on occasions when you need to work under pressure.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking“Self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking.” means becoming aware of your thinking process. It’s a human trait that allows us to step outside what we read or write and ask ourselves, “Does this really make sense?” “Are there other, perhaps better, ways to explain this idea?” Sometimes our thinking is very abstract and becomes clear only through the process of getting thoughts down in words. As a character in E. M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel said, “How can I tell what I think till I see what I say?”Forster, E. M. (1976). Aspects of the novel (p. 99). Oliver Stallybrass (Ed.). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. Did you really write what you meant to, and will it be easily understood by the reader? Successful writing forms a relationship with the audience, reaching the reader on a deep level that can be dynamic and motivating. In contrast, when writing fails to meet the audience’s expectations, you already know the consequences: they’ll move on.

Figure 9.2

Excellence in writing comes from effort.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Learning to write effectively involves reading, writing, critical thinking, and hard work. You may have seen The Wizard of Oz and recall the scene when Dorothy discovers what is behind the curtain. Up until that moment, she believed the Wizard’s powers were needed to change her situation, but now she discovers that the power is her own. Like Dorothy, you can discover that the power to write successfully rests in your hands. Excellent business writing can be inspiring, and it is important to not lose that sense of inspiration as we deconstruct the process of writing to its elemental components.

You may be amazed by the performance of Tony Hawk on a skateboard ramp, Mia Hamm on the soccer field, or Michael Phelps in the water. Those who demonstrate excellence often make it look easy, but nothing could be further from the truth. Effort, targeted practice, and persistence will win the day every time. When it comes to writing, you need to learn to recognize clear and concise writing while looking behind the curtain at how it is created. This is not to say we are going to lose the magic associated with the best writers in the field. Instead, we’ll appreciate what we are reading as we examine how it was written and how the writer achieved success.

Key Takeaway

Success in writing comes from good habits: reading, writing (especially targeted practice), and critical thinking.

Exercises

- Interview one person whose job involves writing. This can include writing e-mails, reports, proposals, invoices, or any other form of business document. Where did this person learn to write? What would they include as essential steps to learning to write for success in business? Share your results with a classmate.

- For five consecutive days, read the business section of your local newspaper or another daily paper. Write a one-page summary of the news that makes the most impression on you. Review your summaries and compare them with those of your classmates.

- Practice filling out an online form that requires writing sentences, such as a job application for a company that receives applications online. How does this kind of writing compare with the writing you have done for other courses in the past? Discuss your thoughts with your classmates.

9.3 Good Writing

Learning Objectives

- Identify six basic qualities that characterize good business writing.

- Identify and explain the rhetorical elements and cognate strategies that contribute to good writing.

One common concern is to simply address the question, what is good writing? As we progress through our study of written business communication we’ll try to answer it. But recognize that while the question may be simple, the answer is complex. Edward P. BaileyBailey, E. (2008). Writing and speaking. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. offers several key points to remember.

Good business writing

- follows the rules,

- is easy to read, and

- attracts the reader.

Let’s examine these qualities in more depth.

Bailey’s first point is one that generates a fair amount of debate. What are the rules? Do “the rules” depend on audience expectations or industry standards, what your English teacher taught you, or are they reflected in the amazing writing of authors you might point to as positive examples? The answer is “all of the above,” with a point of clarification. You may find it necessary to balance audience expectations with industry standards for a document, and may need to find a balance or compromise. BaileyBailey, E. (2008). Writing and speaking. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. points to common sense as one basic criterion of good writing, but common sense is a product of experience. When searching for balance, reader understanding is the deciding factor. The correct use of a semicolon may not be what is needed to make a sentence work. Your reading audience should carry extra attention in everything you write because, without them, you won’t have many more writing assignments.

When we say that good writing follows the rules, we don’t mean that a writer cannot be creative. Just as an art student needs to know how to draw a scene in correct perspective before he can “break the rules” by “bending” perspective, so a writer needs to know the rules of language. Being well versed in how to use words correctly, form sentences with proper grammar, and build logical paragraphs are skills the writer can use no matter what the assignment. Even though some business settings may call for conservative writing, there are other areas where creativity is not only allowed but mandated. Imagine working for an advertising agency or a software development firm; in such situations success comes from expressing new, untried ideas. By following the rules of language and correct writing, a writer can express those creative ideas in a form that comes through clearly and promotes understanding.

Similarly, writing that is easy to read is not the same as “dumbed down” or simplistic writing. What is easy to read? For a young audience, you may need to use straightforward, simple terms, but to ignore their use of the language is to create an artificial and unnecessary barrier. An example referring to Miley Cyrus may work with one reading audience and fall flat with another. Profession-specific terms can serve a valuable purpose as we write about precise concepts. Not everyone will understand all the terms in a profession, but if your audience is largely literate in the terms of the field, using industry terms will help you establish a relationship with your readers.

The truly excellent writer is one who can explain complex ideas in a way that the reader can understand. Sometimes ease of reading can come from the writer’s choice of a brilliant illustrative example to get a point across. In other situations, it can be the writer’s incorporation of definitions into the text so that the meaning of unfamiliar words is clear. It may also be a matter of choosing dynamic, specific verbs that make it clear what is happening and who is carrying out the action.

Bailey’s third point concerns the interest of the reader. Will they want to read it? This question should guide much of what you write. We increasingly gain information from our environment through visual, auditory, and multimedia channels, from YouTube to streaming audio, and to watching the news online. Some argue that this has led to a decreased attention span for reading, meaning that writers need to appeal to readers with short, punchy sentences and catchy phrases. However, there are still plenty of people who love to immerse themselves in reading an interesting article, proposal, or marketing piece.

Perhaps the most universally useful strategy in capturing your reader’s attention is to state how your writing can meet the reader’s needs. If your document provides information to answer a question, solve a problem, or explain how to increase profits or cut costs, you may want to state this in the beginning. By opening with a “what’s in it for me” strategy, you give your audience a reason to be interested in what you’ve written.

More Qualities of Good Writing

To the above list from Bailey, let’s add some additional qualities that define good writing. Good writing

- meets the reader’s expectations,

- is clear and concise,

- is efficient and effective.

To meet the reader’s expectations, the writer needs to understand who the intended reader is. In some business situations, you are writing just to one person: your boss, a coworker in another department, or an individual customer or vendor. If you know the person well, it may be as easy for you to write to him or her as it is to write a note to your parent or roommate. If you don’t know the person, you can at least make some reasonable assumptions about his or her expectations, based on the position he or she holds and its relation to your job.

In other situations, you may be writing a document to be read by a group or team, an entire department, or even a large number of total strangers. How can you anticipate their expectations and tailor your writing accordingly? Naturally you want to learn as much as you can about your likely audience. How much you can learn and what kinds of information will vary with the situation. If you are writing Web site content, for example, you may never meet the people who will visit the site, but you can predict why they would be drawn to the site and what they would expect to read there. Beyond learning about your audience, your clear understanding of the writing assignment and its purpose will help you to meet reader expectations.

Our addition of the fifth point concerning clear and concise writing reflects the increasing tendency in business writing to eliminate error. Errors can include those associated with production, from writing to editing, and reader response. Your twin goals of clear and concise writing point to a central goal across communication: fidelity. This concept involves our goal of accurately communicating all the intended information with a minimum of signal or message breakdown or misinterpretation. Designing your documents, including writing and presentation, to reduce message breakdown is an important part of effective business communication.

This leads our discussion to efficiency. There are only twenty-four hours in a day and we are increasingly asked to do more with less, with shorter deadlines almost guaranteed. As a writer, how do you meet ever-increasing expectations? Each writing assignment requires a clear understanding of the goals and desired results, and when either of these two aspects is unclear, the efficiency of your writing can be compromised. Rewrites require time that you may not have, but will have to make if the assignment was not done correctly the first time.

As we have discussed previously, making a habit of reading similar documents prior to beginning your process of writing can help establish a mental template of your desired product. If you can see in your mind’s eye what you want to write, and have the perspective of similar documents combined with audience’s needs, you can write more efficiently. Your written documents are products and will be required on a schedule that impacts your coworkers and business. Your ability to produce effective documents efficiently is a skill set that will contribute to your success.

Our sixth point reinforces this idea with an emphasis on effectiveness. What is effective writing? It is writing that succeeds in accomplishing its purpose. Understanding the purpose, goals, and desired results of your writing assignment will help you achieve this success. Your employer may want an introductory sales letter to result in an increase in sales leads, or potential contacts for follow-up leading to sales. Your audience may not see the document from that perspective, but will instead read with the mindset of, “How does this help me solve X problem?” If you meet both goals, your writing is approaching effectiveness. Here, effectiveness is qualified with the word “approaching” to point out that writing is both a process and a product, and your writing will continually require effort and attention to revision and improvement.

Rhetorical Elements and Cognate Strategies

Another approach to defining good writing is to look at how it fulfills the goals of two well-known systems in communication. One of these systems comprises the three classical elements of rhetoricThe art of presenting an argument., or the art of presenting an argument. These elements are logos (logic), ethos (ethics and credibility), and pathos (emotional appeal), first proposed by the ancient Greek teacher Aristotle. Although rhetoric is often applied to oral communication, especially public speaking, it is also fundamental to good writing.

A second set of goals involves what are called cognate strategiesWays of framing, expressing and representing a message to an audience., or ways of promoting understanding,Kostelnick, C., & Roberts, D. (1998). Designing visual language: Strategies for professional communicators (p. 14). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. developed in recent decades by Charles Kostelnick and David Rogers. Like rhetorical elements, cognate strategies can be applied to public speaking, but they are also useful in developing good writing. Table 9.2 "Rhetorical Elements and Cognate Strategies" describes these goals, their purposes, and examples of how they may be carried out in business writing.

Table 9.2 Rhetorical Elements and Cognate Strategies

| Aristotle’s Rhetorical Elements | Cognate Strategies | Focus | Example in Business Writing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logos | Clarity | Clear understanding | An announcement will be made to the company later in the week, but I wanted to tell you personally that as of the first of next month, I will be leaving my position to accept a three-year assignment in our Singapore office. As soon as further details about the management of your account are available, I will share them with you. |

| Conciseness | Key points | In tomorrow’s conference call Sean wants to introduce the new team members, outline the schedule and budget for the project, and clarify each person’s responsibilities in meeting our goals. | |

| Arrangement | Order, hierarchy, placement | Our department has matrix structure. We have three product development groups, one for each category of product. We also have a manufacturing group, a finance group, and a sales group; different group members are assigned to each of the three product categories. Within the matrix, our structure is flat, meaning that we have no group leaders. Everyone reports to Beth, the department manager. | |

| Ethos | Credibility | Character, trust | Having known and worked with Jesse for more than five years, I can highly recommend him to take my place as your advisor. In addition to having superb qualifications, Jesse is known for his dedication, honesty, and caring attitude. He will always go the extra mile for his clients. |

| Expectation | Norms and anticipated outcomes | As is typical in our industry, we ship all merchandise FOB our warehouse. Prices are exclusive of any federal, state, or local taxes. Payment terms are net 30 days from date of invoice. | |

| Reference | Sources and frames of reference | According to an article in Business Week dated October 15, 2009, Doosan is one of the largest business conglomerates in South Korea. | |

| Pathos | Tone | Expression | I really don’t have words to express how grateful I am for all the support you’ve extended to me and my family in this hour of need. You guys are the best. |

| Emphasis | Relevance | It was unconscionable for a member of our organization to shout an interruption while the president was speaking. What needs to happen now—and let me be clear about this—is an immediate apology. | |

| Engagement | Relationship | Faithful soldiers pledge never to leave a fallen comrade on the battlefield. |

Key Takeaway

Good writing is characterized by correctness, ease of reading, and attractiveness; it also meets reader expectations and is clear, concise, efficient, and effective. Rhetorical elements (logos, ethos, and pathos) and cognate strategies (clarity, conciseness, arrangement, credibility, expectation, reference, tone, emphasis, and engagement) are goals that are achieved in good business writing.

Exercises

- Choose a piece of business writing that attracts your interest. What made you want to read it? Share your thoughts with your classmates.

- Choose a piece of business writing and evaluate it according to the qualities of good writing presented in this section. Do you think the writing qualifies as “good”? Why or why not? Discuss your opinion with your classmates.

- Identify the ethos, pathos, and logos in a document. Share and compare with classmates.

9.4 Style in Written Communication

Learning Objectives

- Describe and identify three styles of writing.

- Demonstrate the appropriate use of colloquial, casual, and formal writing in at least one document of each style.

One way to examine written communication is from a structural perspective. Words are a series of symbols that communicate meaning, strung together in specific patterns that are combined to communicate complex and compound meanings. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and articles are the building blocks you will use when composing written documents. Misspellings of individual words or grammatical errors involving misplacement or incorrect word choices in a sentence, can create confusion, lose meaning, and have a negative impact on the reception of your document. Errors themselves are not inherently bad, but failure to recognize and fix them will reflect on you, your company, and limit your success. Self-correction is part of the writing process.

Another way to examine written communication is from a goals perspective, where specific documents address stated (or unstated) goals and have rules, customs, and formats that are anticipated and expected. Violations of these rules, customs, or formats—whether intentional or unintentional—can also have a negative impact on the way your document is received.

Colloquial, casual, and formal writing are three common styles that carry their own particular sets of expectations. Which style you use will depend on your audience, and often whether your communication is going to be read only by those in your company (internal communicationsThe sharing and understanding of meaning between individuals, departments, or representatives of the same business.) or by those outside the organization, such as vendors, customers or clients (external communicationsThe sharing and understanding of meaning between individuals, departments, or representatives of the business and parties outside the organization.). As a general rule, external communications tend to be more formal, just as corporate letterhead and business cards—designed for presentation to the “outside world”—are more formal than the e-mail and text messages that are used for everyday writing within the organization.

Style also depends on the purpose of the document and its audience. If your writing assignment is for Web page content, clear and concise use of the written word is essential. If your writing assignment is a feature interest article for an online magazine, you may have the luxury of additional space and word count combined with graphics, pictures, embedded video or audio clips, and links to related topics. If your writing assignment involves an introductory letter represented on a printed page delivered in an envelope to a potential customer, you won’t have the interactivity to enhance your writing, placing an additional burden on your writing and how you represent it.

Colloquial

Colloquial languageAn informal, conversational style of writing. is an informal, conversational style of writing. It differs from standard business English in that it often makes use of colorful expressions, slang, and regional phrases. As a result, it can be difficult to understand for an English learner or a person from a different region of the country. Sometimes colloquialism takes the form of a word difference; for example, the difference between a “Coke,” a “tonic,” a “pop, and a “soda pop” primarily depends on where you live. It can also take the form of a saying, as Roy Wilder Jr. discusses in his book You All Spoken Here: Southern Talk at Its Down-Home Best.Wilde, J., Jr. (2003). You all spoken here: Southern talk at its down-home best. Athens: University of Georgia Press. Colloquial sayings like “He could mess up a rainstorm” or “He couldn’t hit the ground if he fell” communicate the person is inept in a colorful, but not universal way. In the Pacific Northwest someone might “mosey,” or walk slowly, over to the “café,” or bakery, to pick up a “maple bar”—a confection known as a “Long John doughnut” to people in other parts of the United States.

Colloquial language can be reflected in texting:

“ok fwiw i did my part n put it in where you asked but my ? is if the group does not participate do i still get credit for my part of what i did n also how much do we all have to do i mean i put in my opinion of the items in order do i also have to reply to the other team members or what? Thxs”

We may be able to grasp the meaning of the message, and understand some of the abbreviations and codes, but when it comes to business, this style of colloquial text writing is generally suitable only for one-on-one internal communications between coworkers who know each other well (and those who do not judge each other on spelling or grammar). For external communications, and even for group communications within the organization, it is not normally suitable, as some of the codes are not standard, and may even be unfamiliar to the larger audience.

Colloquial writing may be permissible, and even preferable, in some business contexts. For example, a marketing letter describing a folksy product such as a wood stove or an old-fashioned popcorn popper might use a colloquial style to create a feeling of relaxing at home with loved ones. Still, it is important to consider how colloquial language will appear to the audience. Will the meaning of your chosen words be clear to a reader who is from a different part of the country? Will a folksy tone sound like you are “talking down” to your audience, assuming that they are not intelligent or educated enough to appreciate standard English? A final point to remember is that colloquial style is not an excuse for using expressions that are sexist, racist, profane, or otherwise offensive.

Casual

Casual languageInvolves everyday words and expressions in a familiar group context. involves everyday words and expressions in a familiar group context, such as conversations with family or close friends. The emphasis is on the communication interaction itself, and less about the hierarchy, power, control, or social rank of the individuals communicating. When you are at home, at times you probably dress in casual clothing that you wouldn’t wear in public—pajamas or underwear, for example. Casual communication is the written equivalent of this kind of casual attire. Have you ever had a family member say something to you that a stranger or coworker would never say? Or have you said something to a family member that you would never say in front of your boss? In both cases, casual language is being used. When you write for business, a casual style is usually out of place. Instead, a respectful, professional tone represents you well in your absence.

Formal

In business writing, the appropriate style will have a degree of formality. Formal languageFocuses on professional expression with attention to roles, protocol, or appearance. is communication that focuses on professional expression with attention to roles, protocol, and appearance. It is characterized by its vocabulary and syntaxThe grammatical arrangement of words in a sentence., or the grammatical arrangement of words in a sentence. That is, writers using a formal style tend to use a more sophisticated vocabulary—a greater variety of words, and more words with multiple syllables—not for the purpose of throwing big words around, but to enhance the formal mood of the document. They also tend to use more complex syntax, resulting in sentences that are longer and contain more subordinate clauses.

The appropriate style for a particular business document may be very formal, or less so. If your supervisor writes you an e-mail and you reply, the exchange may be informal in that it is fluid and relaxed, without much forethought or fanfare, but it will still reflect the formality of the business environment. Chances are you will be careful to use an informative subject line, a salutation (“Hi [supervisor’s name]” is typical in e-mails), a word of thanks for whatever information or suggestion she provided you, and an indication that you stand ready to help further if need be. You will probably also check your grammar and spelling before you click “send.”

A formal document such as a proposal or an annual report will involve a great deal of planning and preparation, and its style may not be fluid or relaxed. Instead, it may use distinct language to emphasize the prestige and professionalism of your company. Let’s say you are going to write a marketing letter that will be printed on company letterhead and mailed to a hundred sales prospects. Naturally you want to represent your company in a positive light. In a letter of this nature you might write a sentence like “The Widget 300 is our premium offering in the line; we have designed it for ease of movement and efficiency of use, with your success foremost in our mind.” But in an e-mail or a tweet, you might use an informal sentence instead, reading “W300—good stapler.”

Writing for business often involves choosing the appropriate level of formality for the company and industry, the particular document and situation, and the audience.

Key Takeaway

The best style for a document may be colloquial, casual, informal, or formal, depending on the audience and the situation.

Exercises

- Refer back to the e-mail or text message example in this section. Would you send that message to your professor? Why or why not? What normative expectations concerning professor-student communication are there and where did you learn them? Discuss your thoughts with your classmates.

- Select a business document and describe its style. Is it formal, informal, or colloquial? Can you rewrite it in a different style? Share your results with a classmate.

- List three words or phrases that you would say to your friends. List three words or phrases that communicate similar meanings that you would say to an authority figure. Share and compare with classmates.

- When is it appropriate to write in a casual tone? In a formal tone? Write a one- to two-page essay on this topic and discuss it with a classmate.

- How does the intended audience influence the choice of words and use of language in a document? Think of a specific topic and two specific kinds of audiences. Then write a short example (250–500 words) of how this topic might be presented to each of the two audiences.

9.5 Principles of Written Communication

Learning Objectives

- Understand the rules that govern written language.

- Understand the legal implications of business writing.

You may not recall when or where you learned all about nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, articles, and phrases, but if you understand this sentence we’ll take for granted that you have a firm grasp of the basics. But even professional writers and editors, who have spent a lifetime navigating the ins and outs of crafting correct sentences, have to use reference books to look up answers to questions of grammar and usage that arise in the course of their work. Let’s examine how the simple collection of symbols called a word can be such a puzzle.

Words Are Inherently Abstract

There is no universally accepted definition for love, there are many ways to describe desire, and there are countless ways to draw patience. Each of these terms is a noun, but it’s an abstractReferring to an intangible concept. noun, referring to an intangible concept.

While there are many ways to define a chair, describe a table, or draw a window, they each have a few common characteristics. A chair may be made from wood, crafted in a Mission style, or made from plastic resin in one solid piece in nondescript style, but each has four legs and serves a common function. A table and a window also have common characteristics that in themselves form a basis for understanding between source and receiver. The words “chair,” “table,” and “window” are concrete termsDescribes something we can see and touch., as they describe something we can see and touch.

Concrete terms are often easier to agree on, understand, or at least define the common characteristics of. Abstract terms can easily become even more abstract with extended discussions, and the conversational partners may never agree on a common definition or even a range of understanding.

In business communication, where the goal is to be clear and concise, limiting the range of misinterpretation, which type of word do you think is preferred? Concrete terms serve to clarify your writing and more accurately communicate your intended meaning to the receiver. While all words are abstractions, some are more so than others. To promote effective communication, choose words that can be easily referenced and understood.

Words Are Governed by Rules

Perhaps you like to think of yourself as a free spirit, but did you know that all your communication is governed by rules? You weren’t born knowing how to talk, but learned to form words and sentences as you developed from infancy. As you learned language, you learned rules. You learned not only what a word means in a given context, and how to pronounce it; you also learned the social protocol of when to use it and when not to. When you write, your words represent you in your absence. The context may change from reader to reader, and your goal as an effective business communicator is to get your message across (and some feedback) regardless of the situation.

The better you know your audience and context, the better you can anticipate and incorporate the rules of how, what, and when to use specific words and terms. And here lies a paradox. You may think that, ideally, the best writing is writing that is universally appealing and understood. Yet the more you design a specific message to a specific audience or context, the less universal the message becomes. Actually, this is neither a good or bad thing in itself. In fact, if you didn’t target your messages, they wouldn’t be nearly as effective. By understanding this relationship of a universal or specific appeal to an audience or context, you can look beyond vocabulary and syntax and focus on the reader. When considering a communication assignment like a sales letter, knowing the intended audience gives you insight to the explicit and implicit rules.

All words are governed by rules, and the rules are vastly different from one language and culture to another. A famous example is the decision by Chevrolet to give the name “Nova” to one of its cars. In English, nova is recognized as coming from Latin meaning “new”; for those who have studied astronomy, it also refers to a type of star. When the Chevy Nova was introduced in Latin America, however, it was immediately ridiculed as the “car that doesn’t go.” Why? Because “no va” literally means “doesn’t go” in Spanish.

By investigating sample names in a range of markets, you can quickly learn the rules surrounding words and their multiple meaning, much as you learned about subjects and objects, verbs and nouns, adjectives and adverbs when you were learning language. Long before you knew formal grammar terms, you observed how others communicate and learned by trial and error. In business, error equals inefficiency, loss of resources, and is to be avoided. For Chevrolet, a little market research in Latin America would have gone a long way.

Words Shape Our Reality

Aristotle is famous for many things, including his questioning of whether the table you can see, feel, or use is real.Aristotle. (1941). De anima. In R. McKeon (Ed.), The basic works of Aristotle (J. A. Smith, Trans.). New York, NY: Random House. This may strike you as strange, but imagine that we are looking at a collection of antique hand tools. What are they? They are made of metal and wood, but what are they used for? The words we use help us to make sense of our reality, and we often use what we know to figure out what we don’t know. Perhaps we have a hard time describing the color of the tool, or the table, as we walk around it. The light itself may influence our perception of its color. We may lack the vocabulary to accurately describe to the color, and instead say it is “like a” color, but not directly describe the color itself.Russell, B. (1962). The problems of philosophy (28th ed., p. 9). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1912) The color, or use of the tool, or style of the table are all independent of the person perceiving them, but also a reflection of the person perceiving the object.

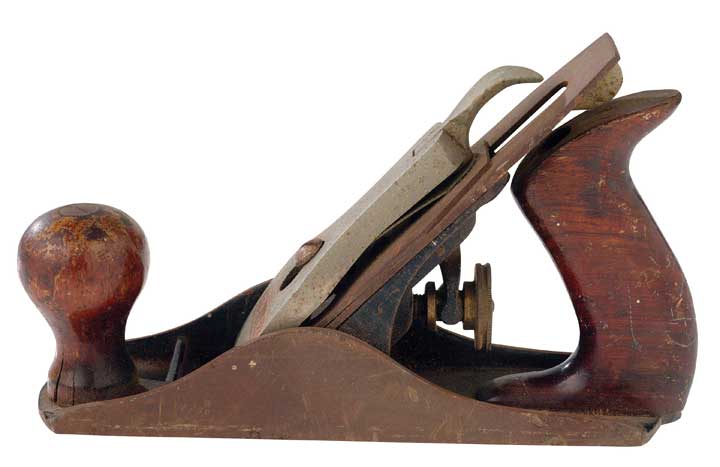

Figure 9.3

Meaning is a reflection of the person perceiving the object or word.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

In business communication, our goal of clear and concise communication involves anticipation of this inability to label a color or describe the function of an antique tool by constructing meaning. Anticipating the language that the reader may reasonably be expected to know, as well as unfamiliar terms, enables the writer to communicate in a way that describes with common reference points while illustrating the new, interesting, or unusual. Promoting understanding and limiting misinterpretations are key goals of the effective business communicator.

Your letter introducing a new product or service relies, to an extent, on your preconceived notions of the intended audience and their preconceived notions of your organization and its products or services. By referencing common ground, you form a connection between the known and the unknown, the familiar and the new. People are more likely to be open to a new product or service if they can reasonably relate it to one they are familiar with, or with which they have had good experience in the past. Your initial measure of success is effective communication, and your long term success may be measured in the sale or new contract for services.

Words and Your Legal Responsibility

Your writing in a business context means that you represent yourself and your company. What you write and how you write it can be part of your company’s success, but can also expose it to unintended consequences and legal responsibility. When you write, keep in mind that your words will keep on existing long after you have moved on to other projects. They can become an issue if they exaggerate, state false claims, or defame a person or legal entity such as a competing company. Another issue is plagiarismRepresenting another’s work as your own., using someone else’s writing without giving credit to the source. Whether the “cribbed” material is taken from a printed book, a Web site, or a blog, plagiarism is a violation of copyright law and may also violate your company policies. Industry standards often have legal aspects that must be respected and cannot be ignored. For the writer this can be a challenge, but it can be a fun challenge with rewarding results.

The rapid pace of technology means that the law cannot always stay current with the realities of business communication. Computers had been in use for more than twenty years before Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, the first federal legislation to “move the nation’s copyright law into the digital age.”United States Copyright Office (1998). Executive summary: Digital millennium copyright act. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.copyright.gov/reports/studies/dmca/dmca_executive.html Think for a moment about the changes in computer use that have taken place since 1998, and you will realize how many new laws are needed to clarify what is fair and ethical, what should be prohibited, and who owns the rights to what.

For example, suppose your supervisor asks you to use your Facebook page or Twitter account to give an occasional “plug” to your company’s products. Are you obligated to comply? If you later change jobs, who owns your posts or tweets—are they yours, or does your now-former employer have a right to them? And what about your network of “friends”? Can your employer use their contact information to send marketing messages? These and many other questions remain to be answered as technology, industry practices, and legislation evolve.Tahmincioglu, E. (2009, October 11). Your boss wants you on Twitter: Companies recognizing value of having workers promote products. MSNBC Careers. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/33090717/ns/business-careers

“Our product is better than X company’s product. Their product is dangerous and you would be a wise customer to choose us for your product solutions.”

What’s wrong with these two sentences? They may land you and your company in court. You made a generalized claim of one product being better than another, and you stated it as if it were a fact. The next sentence claims that your competitor’s product is dangerous. Even if this is true, your ability to prove your claim beyond a reasonable doubt may be limited. Your claim is stated as fact again, and from the other company’s perspective, your sentences may be considered libel or defamation.

LibelThe written form of defamation, or a false statement that damages a reputation. is the written form of defamation, or a false statement that damages a reputation. If a false statement of fact that concerns and harms the person defamed is published—including publication in a digital or online environment—the author of that statement may be sued for libel. If the person defamed is a public figure, they must prove malice or the intention to do harm, but if the victim is a private person, libel applies even if the offense cannot be proven to be malicious. Under the First Amendment you have a right to express your opinion, but the words you use and how you use them, including the context, are relevant to their interpretation as opinion versus fact. Always be careful to qualify what you write and to do no harm.

Key Takeaway

Words are governed by rules and shape our reality. Writers have a legal responsibility to avoid plagiarism and libel.

Exercises

- Define the word “chair.” Describe what a table is. Draw a window. Share, compare, and contrast results with classmates

- Define love. Describe desire. Draw patience.

- Identify a target audience and indicate at least three words that you perceive would be appropriate and effective for that audience. Identify a second audience (distinct from the first) and indicate three words that you perceive would be appropriate and effective. How are the audiences and their words similar or different? Compare your results with those of your classmates.

- Create a sales letter for an audience that comes from a culture other than your own. Identify the culture and articulate how your message is tailored to your perception of your intended audience. Share and compare with classmates.

- Do an online search on “online libel cases” and see what you find. Discuss your results with your classmates.

- In other examples beyond the grammar rules that guide our use of words, consider the online environment. Conduct a search on the word “netiquette” and share your findings.

9.6 Overcoming Barriers to Effective Written Communication

Learning Objective

- Describe some common barriers to written communication and how to overcome them.

In almost any career or area of business, written communication is a key to success. Effective writing can prevent wasted time, wasted effort, aggravation, and frustration. The way we communicate with others both inside of our business and on the outside goes a long way toward shaping the organization’s image. If people feel they are listened to and able to get answers from the firm and its representatives, their opinion will be favorable. Skillful writing and an understanding of how people respond to words are central to accomplishing this goal.

How do we display skillful writing and a good understanding of how people respond to words? Following are some suggestions.

Do Sweat the Small Stuff

Let us begin with a college student’s e-mail to a professor:

“i am confused as to why they are not due intil 11/10 i mean the calender said that they was due then so thats i did them do i still get credit for them or do i need to due them over on one tape? please let me know thanks. also when are you grading the stuff that we have done?”

What’s wrong with this e-mail? What do you observe that may act as a barrier to communication? Let’s start with the lack of formality, including the fact that the student neglected to tell the professor his or her name, or which specific class the question referred to. Then there is the lack of adherence to basic vocabulary and syntax rules. And how about the lower case “i’s” and the misspellings?

One significant barrier to effective written communication is failure to sweat the small stuff. Spelling errors and incorrect grammar may be considered details, but they reflect poorly on you and, in a business context, on your company. They imply either that you are not educated enough to know you’ve made mistakes or that you are too careless to bother correcting them. Making errors is human, but making a habit of producing error-filled written documents makes negative consequences far more likely to occur. When you write, you have a responsibility to self-edit and pay attention to detail. In the long run, correcting your mistakes before others see them will take less time and effort than trying to make up for mistakes after the fact.

Get the Target Meaning

How would you interpret this message?

“You must not let inventory build up. You must monitor carrying costs and keep them under control. Ship any job lots of more than 25 to us at once.”

BypassingThe misunderstanding that occurs when the receiver completely misses the source’s intended meaning. involves the misunderstanding that occurs when the receiver completely misses the source’s intended meaning. Words mean different things to different people in different contexts. All that difference allows for both source and receiver to completely miss one another’s intended goal.

Did you understand the message in the example? Let’s find out. Jerry Sullivan, in his article Bypassing in Managerial Communication,Sullivan, J., Kameda, N., & Nobu, T. (1991). Bypassing in managerial communication. Business Horizons, 34(1), 71–80. relates the story of Mr. Sato, a manager from Japan who is new to the United States. The message came from his superiors at Kumitomo America, a firm involved with printing machinery for the publishing business in Japan. Mr. Sato delegated the instructions (in English as shown above) to Ms. Brady, who quickly identified there were three lots in excess of twenty-five and arranged for prompt shipment.

Six weeks later Mr. Sato received a second message:

“Why didn’t you do what we told you? Your quarterly inventory report indicates you are carrying 40 lots which you were supposed to ship to Japan. You must not violate our instructions.”

What’s the problem? As Sullivan relates, it is an example of one word, or set of words, having more than one meaning.Sullivan, J., Kameda, N., & Nobu, T. (1991). Bypassing in managerial communication. Business Horizons, 34(1), 71–80. According to Sullivan, in Japanese “more than x” includes the reference number twenty-five. In other words, Kumitomo wanted all lots with twenty-five or more to be shipped to Japan. Forty lots fit that description. Ms. Brady interpreted the words as written, but the cultural context had a direct impact on the meaning and outcome.

You might want to defend Ms. Brady and understand the interpretation, but the lesson remains clear. Moreover, cultural expectations differ not only internationally, but also on many different dimensions from regional to interpersonal.

Someone raised in a rural environment in the Pacific Northwest may have a very different interpretation of meaning from someone from New York City. Take, for example, the word “downtown.” To the rural resident, downtown refers to the center or urban area of any big city. To a New Yorker, however, downtown may be a direction, not a place. One can go uptown or downtown, but when asked, “Where are you from?” the answer may refer to a borough (“I grew up in Manhattan”) or a neighborhood (“I’m from the East Village”).

This example involves two individuals who differ by geography, but we can further subdivide between people raised in the same state from two regions, two people of the opposite sex, or two people from different generations. The combinations are endless, as are the possibilities for bypassing. While you might think you understand, requesting feedback and asking for confirmation and clarification can help ensure that you get the target meaning.

Sullivan also notes that in stressful situations we often think in terms of either/or relationships, failing to recognize the stress itself. This kind of thinking can contribute to source/receiver error. In business, he notes that managers often incorrectly assume communication is easier than it is, and fail to anticipate miscommunication.Sullivan, J., Kameda, N., & Nobu, T. (1991). Bypassing in managerial communication. Business Horizons, 34(1), 71–80.

As writers, we need to keep in mind that words are simply a means of communication, and that meanings are in people, not the words themselves. Knowing which words your audience understands and anticipating how they will interpret them will help you prevent bypassing.

Consider the Nonverbal Aspects of Your Message

Let’s return to the example at the beginning of this section of an e-mail from a student to an instructor. As we noted, the student neglected to identify himself or herself and tell the instructor which class the question referred to. Format is important, including headers, contact information, and an informative subject line.

This is just one example of how the nonverbal aspects of a message can get in the way of understanding. Other nonverbal expressions in your writing may include symbols, design, font, and the timing of delivering your message.

Suppose your supervisor has asked you to write to a group of clients announcing a new service or product that directly relates to a service or product that these clients have used over the years. What kind of communication will your document be? Will it be sent as an e-mail or will it be a formal letter printed on quality paper and sent by postal mail? Or will it be a tweet, or a targeted online ad that pops up when these particular clients access your company’s Web site? Each of these choices involves an aspect of written communication that is nonverbal. While the words may communicate a formal tone, the font may not. The paper chosen to represent your company influences the perception of it. An e-mail may indicate that it is less than formal and be easily deleted.

As another example, suppose you are a small business owner and have hired a new worker named Bryan. You need to provide written documentation of asking Bryan to fill out a set of forms that are required by law. Should you send an e-mail to Bryan’s home the night before he starts work, welcoming him aboard and attaching links to IRS form W-4 and Homeland Security form I-9? Or should you wait until he has been at work for a couple of hours, then bring him the forms in hard copy along with a printed memo stating that he needs to fill them out? There are no right or wrong answers, but you will use your judgment, being aware that these nonverbal expressions are part of the message that gets communicated along with your words.

Review, Reflect, and Revise

Do you review what you write? Do you reflect on whether it serves its purpose? Where does it miss the mark? If you can recognize it, then you have the opportunity to revise.

Writers are often under deadlines, and that can mean a rush job where not every last detail is reviewed. This means more mistakes, and there is always time to do it right the second time. Rather than go through the experience of seeing all the mistakes in your “final” product and rushing off to the next job, you may need to focus more on the task at hand and get it done correctly the first time. Go over each step in detail as you review.

A mental review of the task and your performance is often called reflectionA mental review of the task and your performance.. Reflection is not procrastination. It involves looking at the available information and, as you review the key points in your mind, making sure each detail is present and perfect. Reflection also allows for another opportunity to consider the key elements and their relationship to each other.

When you reviseChange one word for another, make subtle changes, and improve a document. your document, you change one word for another, make subtle changes, and improve it. Don’t revise simply to change the good work you’ve completed, but instead look at it from the perspective of the reader—for example, how could this be clearer to them? What would make it visually attractive while continuing to communicate the message? If you are limited to words only, then does each word serve the article or letter? No extras, but just about right.

Key Takeaway

To overcome barriers to communication, pay attention to details; strive to understand the target meaning; consider your nonverbal expressions; and review, reflect, and revise.

Exercises

- Review the example of a student’s e-mail to a professor in this section, and rewrite it to communicate the message more clearly.

- Write a paragraph of 150–200 words on a subject of your choice. Experiment with different formats and fonts to display it and, if you wish, print it. Compare your results with those of your classmates.

- How does the purpose of a document define its format and content? Think of a specific kind of document with a specific purpose and audience. Then create a format or template suitable to that document, purpose, and audience. Show your template to the class or post it on a class bulletin board.

- Write one message of at least three sentences with at least three descriptive terms and present it to at least three people. Record notes about how they understand the message, and to what degree their interpretations are the same of different. Share and compare with classmates.

9.7 Additional Resources

Visit AllYouCanRead.com for a list of the top ten business magazines. http://www.allyoucanread.com/top-10-business-magazines

The Wall Street Executive Library presents a comprehensive menu of business Web sites, publications, and other resources. http://www.executivelibrary.com

The Web site 4hb.com (For Home Business) provides many sample business documents, as well as other resources for the small business owner. http://www.4hb.com/index.html

The Business Owner’s Toolkit provides sample documents in more than a dozen categories from finance to marketing to worker safety. http://www.toolkit.com/tools/index.aspx

Words mean different things to different people—especially when translated from one language to another. Visit this site for a list of car names “que no va” (that won’t go) in foreign languages. http://www.autoblog.com/2008/04/30/nissan-360-the-otti-and-the-moco

Visit “Questions and Quandaries,” the Writer’s Digest blog by Brian Klems, for a potpourri of information about writing. http://blog.writersdigest.com/qq

Appearance counts. Read an article by communications expert Fran Lebo on enhancing the nonverbal aspects of your document. http://ezinearticles.com/?The-Second-Law-of-Business-Writing---Appearance-Counts&id=3039288

Visit this site to access the SullivanSullivan, J., Kameda, N., & Nobu, T. (1991). Bypassing in managerial communication. Business Horizons, 34(1), 71–80. article on bypassing in managerial communication. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1038/is_n1_v34/ai_10360317