This is “Mapping a Text”, section 9.6 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

9.6 Mapping a Text

Many digital literary scholars focus on geospatial technologies to look at literature in new ways enabled by new technologies. In his work Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History, Franco Moretti argues that creating maps of the spaces described in literary texts can give scholars insight into those texts in a way that their words alone cannot: “Literary mapsA map that traces spatial elements within a literary work, such as plotting the locations characters visit within a novel.…are a good way to prepare a text for analysis,” Moretti argues, “You choose a unit—walks, lawsuits, luxury goods, whatever—find its occurrences, place them in space…with a little luck, these maps will be more than the sum of their parts: they will possess ‘emerging’ qualities, which were not visible at the lower level.”Franco Moretti, Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History (London: Verso, 2005), 53. In other words, by mapping specific elements within texts, critics can gain a new perspective on how those elements relate to one another and to other textual elements. If, for instance, we map the locations that characters visit in Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway, we might spot interesting relationships between the inner lives of the characters (as revealed in the text of the novel) and the exterior world of the modern, urban London they travel through (as revealed on the map).

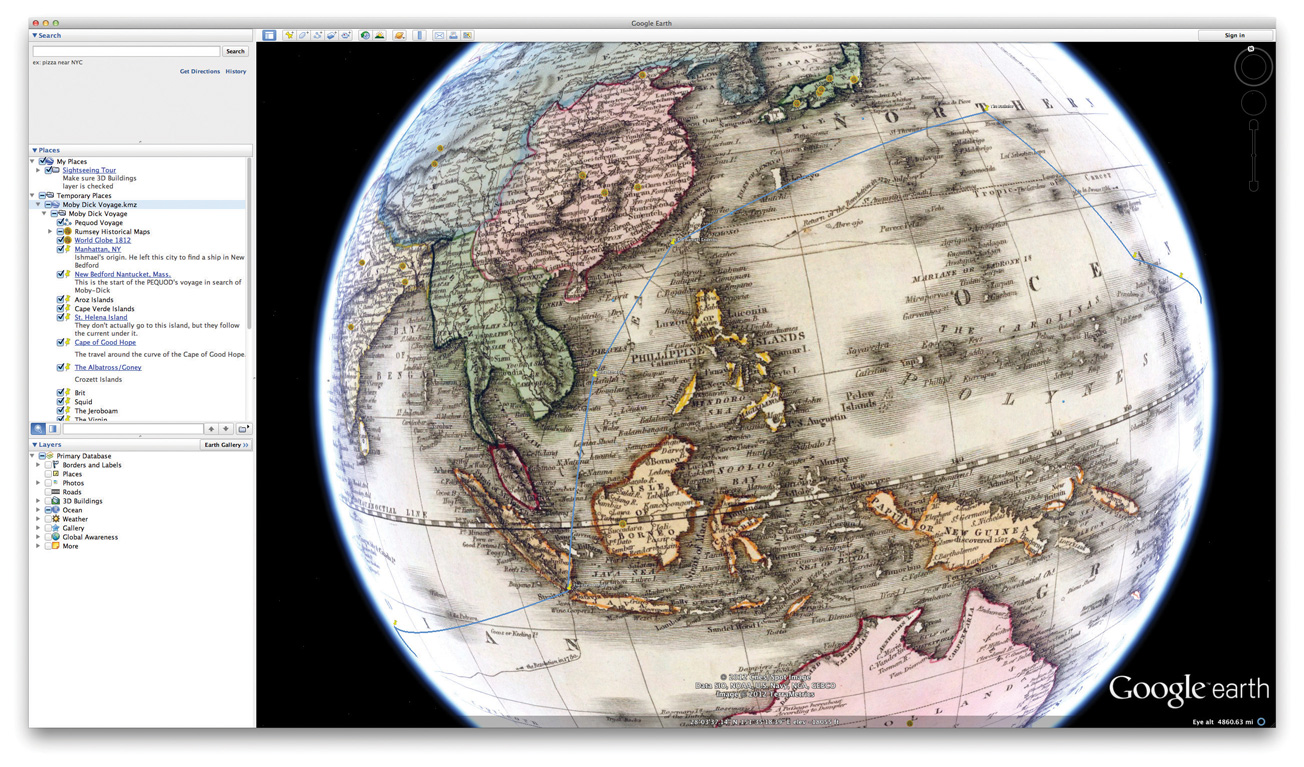

Maria is a student in a sophomore-level literature class that has just finished Melville’s voluminous novel Moby-Dick (http://www.melville.org/diCurcio/bib.htm).Robert A. diCurcio, ed., Nantucket’s Tried-Out Moby-Dick: Robert A. diCurcio’s Companion Reader to Melville’s Masterpiece (Nantucket, MA: Aeternium, 1996), http://www.melville.org/diCurcio/bib.htm. Maria has already written one paper about Moby-Dick—a psychological analysis of the monomaniacal captain in the novel, Ahab—and wants to do something different for her final class project. Maria is very interested in the scope of the Pequod’s voyage, and so she decides to map the ship’s journey through the novel. She hopes that mapping the ship’s journey might illuminate other aspects of the novel that she had not previously considered. Fortunately, the free Google EarthFree software that allows users to plot points on a globe, annotating them with contextual information. When combined with David Rumsey’s Historical Maps Collection, Google Earth allows users to view the globe as it was described at previous points in history. software makes it easy to create detailed maps—even literary maps like the one Maria envisions.

Maria’s Process

- After speaking with her professor about how to start such a project, Maria downloads the free Google Earth software (http://www.google.com/earth/index.html), which will give her a platform to plotting spatial data and visualizing the voyage on an accurate, interactive globe.

- Maria then combs through the novel, looking for places where Melville specifically names the Pequod’s location. Maria uses a map hand-drawn by Everett Henry in 1956 (and available online at http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tri064.html) to double-check her findings from the text.Everett Henry, The Voyage of the Pequod from the Book Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1956), map, American Treasures of the Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tri064.html.

- Maria then begins adding place markers in Google Earth for each of these locations from the novel. She adds some descriptive text to each place marker describing what event from the novel happened there. For a tutorial on adding place markers in Google Earth, see the following video: http://support.google.com/earth/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=148142&topic=2376990&ctx=topic.“Creating a New Placemark,” Google Earth, http://support.google.com/earth/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=148142&topic=2376990&ctx=topic.

- Maria also draws paths between the place markers she has created, so that the events in the novel can be followed in chronological order. For a tutorial on drawing paths, see the following video: http://support.google.com/earth/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=148072.“Drawing Paths and Polygons,” Google Earth, http://support.google.com/earth/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=148072.

Your Process

- Pick a work that you’ve read in class recently. Download Google Earth and begin adding place markers from that work. What new ideas about the work begin to emerge as you create these place markers? Does working with the text in this way change the kinds of questions you ask about it? Jot down your thoughts.

After Maria adds her place markers, she can move from location to location in Google Earth and trace the Pequod’s voyage. She’s not entirely satisfied with her map, however. By default, Google Earth includes modern geographic information, and the events of Melville’s novel, published in 1852, look anachronistic on a twenty-first-century map. Maria brings her concern to her professor, who recommends she look at the David Rumsey Map Collection (http://www.davidrumsey.com), a freely distributed collection of scanned historical maps. The Rumsey Collection even makes many of their historical maps available as a KMZA file format that allows users to share events plotted in Google Earth with other users. file that can be easily opened in Google Earth (http://www.davidrumsey.com/view/google-earth).David Rumsey, David Rumsey Map Collection, http://www.davidrumsey.com/view/google-earth.

Maria’s Process

- Maria downloads the Rumsey Map Collection into Google Earth. Now she can turn on map layers that depict the globe as it was drawn during the nineteenth century, the time of Moby Dick’s composition. These historical maps give her project a greater visual punch and ground her map in the time and place of the literature she’s working with.

- Maria puts her work—the place markers and historical map—together in a KMZ file that she can upload to her website, share with her peers, and submit to her professor (for a basic tutorial on creating a KMZ file, see the following instructions: http://support.google.com/earth/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=148150).“Saving Places Data,” Google Earth, July 16, 2012, http://support.google.com/earth/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=148150.

- Finally, Maria considered what new insights she has gained on Melville’s novel by mapping it and writes a short reflection paper describing those insights. That reflection paper is included here.

Your Process

- Download the Rumsey Collection’s KMZ file and open it in Google Earth. Explore the historical maps in the file. Do any of them strike you as applicable to particular literary works you’ve read in class? Which ones and why? Add your thoughts.

Figure 9.1 Maria’s Final Map

© 2012 Google.

Maria’s final map, which you can see in Figure 9.1 "Maria’s Final Map", allows other students and scholars to follow the Pequod’s voyage for themselves, and even (if they wish) to layer different historical maps under it. You can download Maria’s KMZ yourself (http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/sites/all/files/pennington-mobydickvoyage.kmz) and experiment with the work she did. Now let’s look at Maria’s reflection paper, in which she explains what building this map taught her about Melville’s novel and the nineteenth-century whaling industry.