This is “Reader-Response Theory: An Overview”, section 6.2 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

6.2 Reader-Response Theory: An Overview

Let’s begin with the famous opening from Jane Austen’s Emma (1816):“Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.”Jane Austen, Emma (New York: Penguin Classics, 2011).

Oh, that Emma Woodhouse. “Handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition,” certainly, but also vain, proud, and a mischievous-matchmaker in those things related to love. Not much of a character to base a novel on, the reader might muse. Austen was nervous about her creation of Emma, for as she wrote in a letter: “I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.” Yet Austen does exactly this: in Emma, she creates a character that taxes the reader’s patience, one the author recognizes that readers may not like.

Austen’s comments on Emma point to the fact that readers identify with characters in a novel. And we can extrapolate further: readers like or dislike what they read; readers are moved to joy, anger, sadness, and so on by a literary work; and readers read literature from a personal level. For an author, this “reader response” is of utmost importance, as Austen most certainly realizes. If readers do not like Emma, do not empathize with her on some emotional level, then they will dislike the novel.

Class Process

- List the literary works that you were told were great or important but that you actually disliked. Your instructor should also share his or her dislikes. This should lead to a lively discussion.

You will see that “likes” and “dislikes” are important markers in reader-response theory. Here’s an example: in Letters to Alice on First Reading Jane Austen (1984), the author, Fay Weldon, writes to her niece Alice, trying to convince her of the importance of Austen. “You tell me in passing,” writes Weldon, “that you are doing a college course in English Literature, and are obliged to read Jane Austen; that you find her boring, petty and irrelevant and, that as the world is in crisis, and the future catastrophic, you cannot imagine what purpose there can be in your reading her.”Fay Weldon, Letters to Alice on First Reading Jane Austen (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2011), 11. Weldon responds, “Emma opens with a paragraph which sends shivers of pleasure down my spine: it glitters with sheer competence: with the animation of the writer who has discovered power: who is at ease in the pathways of the City of Invention. Here is Emma, exciting envy in the heart of the reader and also, one suspects, the writer—and now, she declares, Emma will be undone; and I, the writer, and you, the reader, will share in this experience.”Fay Weldon, Letters to Alice on First Reading Jane Austen (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2011), 96. Weldon, of course, is responding to Austen on a very personal level—on the gut level we should say—which can make one have “shivers of pleasure” or “exciting envy” or “share in this [reading] experience.” What Weldon does to Austen and Emma is perform a reader-response interpretation.

Reader-response literary criticism recognizes the simple fact that readers respond to literature on an emotional level and that such responses are important to the understanding of the work. Long ago, even Aristotle recognized how important an audience’s reaction is to tragedy, for a key to tragedy is catharsisAn emotional release. The Greek philosopher Aristotle argued that plays, or literature, should provide this experience for their audience., the purging of the audience’s emotions. If you recall from Chapter 1 "Introduction: What Is Literary Theory and Why Should I Care?", the concept of the affective fallacy was central to the New Critical methodology—a reader was never to confuse the interpretation of the literary work with the “feeling” she or he had while reading. These New Critics warned the reader that affective responses lead only to subjectivity; thus New Critics suggested that the reader pay close attention to the intricacies of the text under observation for meaning, for the text as a well-wrought urn contains meaning.

Reader-response critics, on the other hand, embrace the affective fallacy (what reader-response critic Stanley Fish has called the “affective fallacy fallacyTerm coined by Stanley Fish to express reader-response critics’ rejection of the New Critics’ affective fallacy. Reader-response critics believe that we should not repress our personal responses to literature but rather explore them in our writing.”), for they believe that a reader’s affective response is importance to criticism.Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998). Instead of focusing on literature as a well-wrought urn, reader-response critics focus on the reader, who “completes” or “activates” the text as he or she reads. In a sense, the reader becomes the most important element in the reading process, supplanting even the author.

When you think about it, reader-response criticism makes perfect sense. How many times have you become so immersed in a work that you are oblivious to the world around you? If you like fantasy literature, you might still recall the first time you read the Harry Potter series—you were transported out of your Muggle world into the magical Hogwarts, where Harry and his friends battle the dark forces of the one we should not name. How many of you stood in line to get your copy of the latest Harry Potter novel at midnight? Or camped out at the theater to be one of the first to see the final installment of The Deathly Hallows? There may even be a few of you who are not Potter fans, but be warned—don’t share those thoughts too readily! A case point: one of the editors of this textbook, John Pennington, found this out quite clearly. He teaches a general-education course called Science Fiction and Fantasy, which attracts die-hard fans of these popular forms of fiction. When the first volume of the Harry Potter series came out, he was approached by a student, who told him that this was the best fantasy literature since J. R. R. Tolkien, maybe even better. Quite a claim, and one that came from a very intelligent student who clearly was excited about Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone! However, Pennington found that he did not enjoy the novel as much as his student had. So he read the next volume, and the next, and…you get the picture. To put it bluntly, he wasn’t that impressed with the Harry Potter series. He eventually published an article in The Lion and the Unicorn, a critical journal that focuses on children’s literature. In that article, he critiques the Harry Potter series as ineffective—shall we say, “failed”—fantasy literature.John Pennington, “From Elfland to Hogwarts, or the Aesthetic Trouble with Harry Potter,” The Lion and the Unicorn 26, no. 1 (2002): 78–97, http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lion_and_the_unicorn/toc/uni26.1.html.

Over the years, he has received emails from students who are doing research papers on Harry Potter. To demonstrate that literature is often read with passion, read the following e-mail to John Pennington, which he received from a student who was doing such a research paper:

Hello, Professor Pennington. My name is Emily. I'm a senior English major at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, TX.

For my honors thesis, I have been doing research on fantasy literature (I’m making a comparison of magical and fantastic creatures in American and British literature) and in my search, I stumbled across your piece “From Elfland to Hogwarts, or the Aesthetic Trouble with Harry Potter.” I won’t lie to you, I am an avid Harry Potter fan. I am the president of the St. Mary’s Harry Potter club, called Dumbledore’s Army.

Mary’s Harry Potter club, called Dumbledore’s Army. I was just wondering if your feelings about certain aspects of the Harry Potter series have changed now that all the books have been released? I definitely agreed with some of your opinions and arguments (even as a little girl reading the books I made the connection between Tolkien/Rowling and Lewis/Rowling), but there are also instances in which I feel you were being too harsh. For instance, you said that while Voldemort was clearly the representation of the archetype for evil, there was none for good. I disagree. I don't believe that the figure for good needs to be a person or being at all. Instead, in the case of the Harry Potter, the symbol of the good archetype is love. Although, arguably, good and love could be seen as synonyms in some cases (through the right analytic lens), I think that love’s manifestations in the Harry Potter series are what truly combats Voldemort (rather than Harry’s attempts at battle—another aspect I, and indeed Harry, agree with you on: all he had was luck) and therefore become the figure of good.

I did find your piece helpful for my research and I do plan to read more of your published works in the future.

One other question: Do you often get e-mails from people who are disgruntled by your criticism of the Potter series? I would imagine the answer is yes.

Thank you for your time.

—Emily Bryant-Mundschau

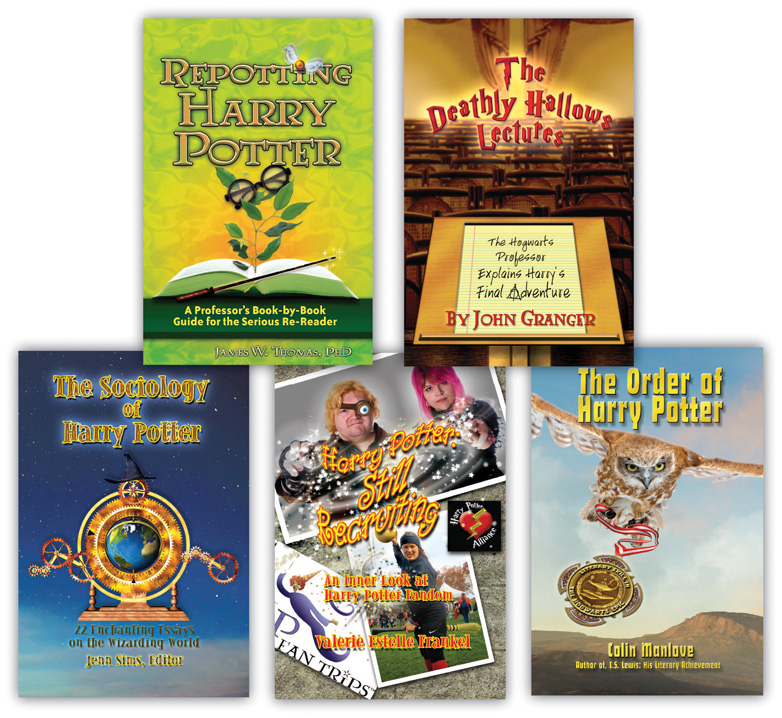

One should not do battle with Dumbledore’s Army! In a follow-up email, where John admited to Emily that his critical views of Harry Potter had not really changed, he also added that he was a little disappointed that Rowling had indicated in an interview about her first novel for adults—The Casual Vacancy (2012)—that she didn’t see herself as a role model for children. Emily responded: “If it hadn’t been for getting a copy of The Sorcerer’s Stone in the 3rd grade, I may not be an English major now. I think a lot of the English majors of my generation are proof that she is a role model for children. Also, I think she must be intentionally ignoring the fact that there is a Harry Potter amusement park…how could kids not adore her?” Emily and John, interestingly, were acting as both critic and fan (or nonfan in John’s case). In other words, readers are to a degree torn between the role of being an objective critic and a subjective fan, a tension that reader-response theory can help explain. Some publishers, in fact, concentrate on critical works on Harry Potter, creating a critical industry that extolls the virtues of the Harry Potter series. Winged Lion/Zossima Press is just one example, and the titles highlight how scholarly investigation becomes fused with personal enthusiasm for the books.

Book covers courtesy of Winged Lion/Zossima Press.

But there’s a flip side to the “positive” reading experience, too. How many times have you become so irritated by a work—or by a piece of criticism!—that you failed to finish it or dreaded every second while you were between the pages? Some may never develop a “taste” for Henry James, for example. And as much as you might admire Moby-Dick (1851) by Herman Melville, you must admit that the so-called cetological center does tax a reader’s patience.

Your Process

- List your three favorite works of literature and write a short paragraph for each explaining why you like them so much.

- Now do the same for your three least favorite works. Why do you dislike them?

- Do you notice any patterns in the works you like and dislike? Why do you suppose you feel the way you do about these works?

- Are there any works that you disliked upon initial reading but grew to like later? Or works you initially loved but now find tiring? Explain.

- Choose either one of the likes or dislikes and consider using the work as the text for your reader-response paper. The following are some key guiding questions you can ask after reading the overview of the types of reader-response theory: Why do I like or dislike this work so much? How do I read this work in a way that might explain my attitude toward the work? Does the work touch on—or challenge—my identity theme? Does my reading connect to an interpretive community? Does my gender, race, class, sexual orientation, or another aspect of my identity have anything to do with my response?

Class Process

- List your favorite literary works that you read primarily as a fan.

- Does this fan favorite hold up to critical scrutiny? Why or why not?

- How do you negotiate this tension between being a fan and a critic?

- Have your instructor list these fan favorites on the board.

- Discuss the tension between fan and critic using these examples.

- Choose either one of the likes or dislikes you listed and consider using the work as the text for your reader-response essay. The following are some key guiding questions you can ask after reading the overview of the types of reader-response theory: Why do I like or dislike this work so much? How do I read this work in a way that may explain my attitude toward the work? Does the work touch on—or challenge—my identity theme? Does my reading connect to an interpretive community? Does my gender, race, class, sexual orientation, or another aspect of my identity have anything to do with my response?

Now that we have acknowledged the fact that personal responses are an important component to the reading process—and to all literary discussion—we can begin learning about the variety of reader responses. As a New Critic, you remember, you scrutinized the text carefully; as a reader-response critic you will discover how your personal likes and dislikes shape your interpretation of a work.