This is “Introduction: What Is Literary Theory and Why Should I Care?”, chapter 1 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 1 Introduction: What Is Literary Theory and Why Should I Care?

Learning Objectives

- Examine the kinds of questions that literary theories attempt to answer.

- Explore the relevance of literary theory to undergraduate studies.

- Review the steps of the writing process.

- Develop a plan for engaging with the writing process in a literature class.

- Summarize the elements of effective academic argument.

1.1 Literary Snapshot: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

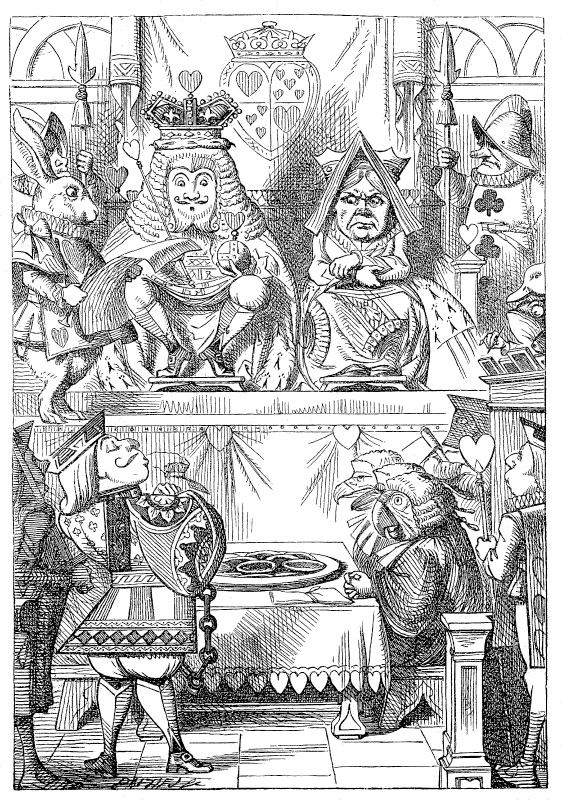

In the final chapter of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Alice attends the trial of the Knave of Hearts, who has been accused of stealing the Queen of Hearts’s tarts. You can read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass by accessing them at http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html and http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html.

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

Read the following exchange, which takes place in the midst of that trial:

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. “Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?” he asked.

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:—

“They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

Don’t let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.”

“That’s the most important piece of evidence we’ve heard yet,” said the King, rubbing his hands; “so now let the jury—”

“If any one of them can explain it,” said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn’t a bit afraid of interrupting him), “I’ll give him sixpence. I don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it.”

The jury all wrote down on their slates, “She doesn’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it,” but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

“If there’s no meaning in it,” said the King, “that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any. And yet I don’t know,” he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; “I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. ‘—said I could not swim—’ you can’t swim, can you?” he added, turning to the Knave.Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. With Forty-Two Illustrations by John Tenniel (New York: D. Appleton, 1927; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1998), chap. 12, http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html.

Perhaps you’ve been in a literature classroom where you felt just like Alice: where it seemed like your teacher or your classmates could find meaning in stories, poems, and plays that you just couldn’t find. Perhaps you have even decided that you “don’t like English” because of such experiences. We hope with this book to help you rethink your approach to literary works so that you will find meaning in a wide range of texts.

This textbook aims to give you practical tools for approaching literary works that will ease some common anxieties that student readers feel in literature classrooms. This text will also show you how to apply those tools when you are asked to write literary analyses. We call those tools “literary theories.”

Your Process

- Have you ever wondered how your teachers or your classmates develop their ideas about literary works? Have you felt confused when reading stories, poems, plays, or essays, and unsure of how to begin interpreting them? Write a bit about your previous experiences in English classes.

- What does the word “theory” mean to you? Write your definition of the word.

1.2 What Is Literary Theory?

When you hear the word “theory,” you might think first of the natural sciences, rather than of literature. In the sciences, theories are systems for understanding how an aspect of the world works: they can be used to explain past phenomena and predict future behavior. Thus we hear about the theory of evolution or the search for the unified theory of the universe.

Theory doesn’t mean exactly the same thing in literature. However, literary scholars do understand their subject through literary theoriesA broad term that encompasses a range of approaches to interpreting literary texts. Different schools of literary theory emphasize specific priorities and approaches to the study of literature., which are intellectual models that seek to answer a number of fundamental interpretive questions about literature. In How to Do Theory, literary critic Wolfgang Iser suggests that the natural sciences (and the social sciences to a large part) operate under hard-coreTheory that is based on fact, leading to problem-solving solutions. The foundation of the natural and (to a degree) the social sciences. theories, whereas the humanities use soft-coreTheory that is based on questioning and predicting, leading to the mapping of ideas, not necessarily solutions. The foundation of the humanities, particularly literary studies. theories.Wolfgang Iser, How to Do Theory (Maiden, MA: Blackwell, 2006). Simply put, hard-core theories lead to problem solving and are governed by general laws and rules; they predict and rely on objective fact. Soft-core theories, on the other hand, do not problem solve but predict—they map ideas and are not necessarily governed by laws but by metaphors and images.

Thus literary scholars use theories that are more descriptive of ideas—which map ideas more than quantify them. Such scholars are guided by questions that may include the following:

- What exactly do we mean by “literature”? What counts as literature, and what does not?

- Can (and should) we determine the value or worth of literary works? If so, how should we go about this task? If not, why not?

- To what extent does a given text reflect its author and/or the historical moment of its composition?

- What are the political and social ramifications of literary texts and of the ways we study them?

These are very broad versions of the questions that literary scholars ask in their work, but you can probably already see that different scholars are likely to have very different answers to many of them. Thus we often talk about different “schools” of literary theory. Each school prioritizes certain concerns for talking about literature while deemphasizing others. Thus one critic might focus on the representation of women within a given story or poem (feminist theory), while another critic might concentrate on representations of unconscious desire in that same text (psychoanalytical theory). Though they’re studying the same text, these two critics may come to very different conclusions about what is most interesting in that text and why.

This book will walk you through many of the primary schools that have shaped literary theory over the past century. Each chapter aims not to simply define a given theory but to show what it looks like in practice. In order to teach you how to employ literary theories, in each chapter we walk you through a sample student paper that demonstrates how other undergraduates have used a given theory to better understand a particular story, poem, play, or other literary work.

1.3 Why Study Literary Theory?

In his essay “Disliking Books at an Early Age,” literary scholar Gerald Graff talks about how he struggled as a child to see the point of literature. “Literature and history,” he recalls, “had no apparent application to my experience.”Gerald Graff, “Disliking Books at an Early Age,” Lingua Franca: The Review of Academic Life 2, no. 6 (September–October 1992): 45–51, JSTOR. Even in college, Graff says, he “continued to find ‘serious’ reading painfully difficult and alien.”Gerald Graff, “Disliking Books at an Early Age,” Lingua Franca: The Review of Academic Life 2, no. 6 (September–October 1992): 45–51, JSTOR. This all changed for Graff when he encountered critical debates over the interpretation of Mark Twain’s novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1876). He read about critics who disagreed over the book’s meaning, value, and attitudes toward race. He realized that the conversations he’d been having with his classmates about the book in class discussion “were not too far from the thoughts of famous published critics,” which gave Graff a feeling of power and excitement about reading he’d never felt before.Gerald Graff, “Disliking Books at an Early Age,” Lingua Franca: The Review of Academic Life 2, no. 6 (September–October 1992): 45–51, JSTOR.

We hope you will feel that same power and excitement about reading as you learn about critical debates in literary study and begin to contribute to them in your own papers. Literature isn’t made up of inscrutable texts that can be deciphered only by a chosen few who have learned to speak in a secret code. Literature is written by people—talented people perhaps, but people nonetheless. And the concerns of literary critics are concerns that many people share: What does this work say about the human condition? How does it convey its message? Does it portray its subjects fairly? What political or social ideas does it advance? Literature has many potential meanings, and literary theory gives scholars different avenues to uncover those meanings.

By asking theoretical questions of the novels, stories, poems, plays, and essays that you read in your literature class, you can begin to grasp works that may seem ineffable—impenetrable—if you try to uncover a single, “correct” interpretation for them. In short, literary theory can give you a toolbox for approaching any literary text: a set of interpretive moves that can help you figure out where to start when your instructor asks you to comment on a work in class or develop a paper topic.

1.4 What Is the Writing Process?

Even the most talented writers rarely get a piece right in their first draft. What’s more, few writers create a first draft through a single, sustained effort. Instead, the best writers understand that writing is a process: it takes time; sustained attention; and a willingness to change, expand, and even delete words as one writes. Good writing also takes a willingness to seek feedback from peers and mentors and to accept and use the advice they give. In this book, we will refer to and model the writing processThe series of steps (e.g., prewriting, researching, drafting, and revising) that contribute to a final, polished paper. This process is not linear but recursive, as writers shuttle back and forth in these steps as they compose., showing how student writers like yourself worked toward compelling papers about literary works.

In this video (http://bigthink.com/ideas/25140), the decorated modern novelist Salman Rushdie, the author of such books as Midnight’s Children and Haroun and the Sea of Stories, talks about his own writing process.Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories (New York: Penguin, 1991); Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses (New York: Random House, 2008). Writing, Rushdie insists, “is not inspiration; it’s concentration.”Salman Rushdie, “Inspiration Is Nonsense,” interview by Max Miller, directed by Jonathan Fowler, Big Think, video, November 29, 2010, http://bigthink.com/ideas/25140. Rushdie even calls the idea of pure inspiration “nonsense,” saying that writing is “exploratory” and “more a process of discovery.”Salman Rushdie, “Inspiration Is Nonsense,” interview by Max Miller, directed by Jonathan Fowler, Big Think, video, November 29, 2010, http://bigthink.com/ideas/25140. Rushdie is talking about writing fiction, but his insight applies just as well to writing critical papers for a college class: good academic writing requires that you devote time and energy to exploring and discovering new ideas. Fortunately, this means you should not panic if a brilliant paper idea doesn’t appear when you first start thinking about a paper topic. If you commit to the writing process the ideas will come.

Your Process

- How do you typically approach writing assignments in your classes? When do you start working? Do you employ any prewriting techniques?

- Have you ever been given the chance to revise your writing after receiving feedback from your peers or your instructor? How did the act of revising change your relationship to your paper?

Good writing takes, above all, planning and organization. If you wait until the night before a written assignment is due to begin, your hurrying will supersede the necessary steps of prewriting, researching, outlining, drafting, revising, seeking feedback, and re-revising. Those stages look something like this:

Prewriting

Many of the activities we’ll ask you to do in the “Your Process” sections of this book will be prewritingShort, informal activities that help writers generate ideas for longer projects (e.g., freewriting or journaling). activities. We’ll ask you to reflect on your reading, to make connections between your experiences and our text, and to jot down ideas spurred by your engagement with the theories presented here. It’s from activities like these that writers often get their ideas for writing. The more engaged you are as a reader, the more engaged you’ll be when the time comes to write.

Researching

This book will also help you start the research process, in which you hone in on those aspects of a given literary text that interest you and seek out a deeper understanding of those aspects. Literary researchers read not only literary texts but also the work of other literary scholars and even sources that are indirectly related to literature, such as primary historical documents and biographies. In other words, they seek a wide range of texts that can supplement their understanding of the story, poem, play, or other text they want to write about. As you research, you should keep prewriting, keeping a record of what you agree with, what you disagree with, and what you feel needs further exploration in the texts you read.

Outlining

To write well you should have a plan. As you write, that plan may change as you learn more about your topic and begin to fully understand your own ideas. However, papers are easier to tackle when you first sketch out the broad outline of your ideas. Committing those ideas to paper will help you see how different ideas relate to one another (or don’t relate to one another). Don’t be afraid to revise your outline—play around with the sequence of your ideas and evidence until you find the most logical progression.

Drafting

The most important way to improve your writing is to start writing! Because you’re treating writing as a process, it’s not important that every word you type be perfectly chosen, or that every sentence be exquisitely crafted. When you’re drafting, the most important thing is that you get words on paper. Follow your outline and write.

Revising

After you’ve committed words to paper (or, more accurately, to your computer screen), you can go back and shape them more deliberately through revisionThe stage of the writing process in which a writer reviews his or her work with an eye toward coherence of argument and elegance of expression. During revision, a writer will make often substantial changes to his or her writing that will help his or her readers follow the piece’s claims. Often a writer will incorporate or respond to the suggestions of peer and expert reviewers during the revision stage.. Cognitive research has shown that a significant portion of reading is actually remembering. As a result, if you read your work immediately after writing it, you probably won’t notice any of the potential problems with it. Your brain will “fill in the gaps” of poor grammar, misspelling, or faulty reasoning. Because of this, you should give yourself some time in between drafting and revising—the more time the better. As you revise, try to approach your text as your readers will. Ask yourself skeptical questions (e.g., Are there clear connections between the different claims I’m making in this paper? Do I provide enough evidence to convince someone to believe my claims?). Revisions can often be substantial: you may need to rearrange your points, delete significant portions of what you’ve written, or rewrite sentences and paragraphs to better reflect the ideas you have developed while writing. Most importantly, you should revise your introduction several times. Writers often work into their strongest ideas, which then appear in their conclusions but not (if they do not revise) their introductions. Make sure that your introduction reflects the more nuanced claims that appear in the body and conclusion of your paper.

Seeking Feedback

Even after years of practice revising your writing, you’ll never be able to see your writing in an entirely objective light. To really improve your writing, you need feedback from others who can identify where your ideas are not as clear as they should be. You can seek feedback in a number of ways: you can make an appointment in your college’s writing center, you can participate in class peer-review workshops, or you can talk to your instructor during his or her office hours. If you will have a chance to revise your paper after your instructor grades it, his or her comments on that graded draft should be considered essential feedback as you revise.

A key notion that drives this textbook is peer review: we believe that you should share your writing with your peers, your classmates. For each chapter in this book, we suggest that you conduct peer review with one or two classmates. We provide peer-review guides for each chapter that can be accessed in Chapter 10 "Appendix A: Peer Review Sheets".

Re-Revising

One you’ve garnered feedback on your writing, you should use that feedback to revise your paper yet again. You should not, however, simply make every change that your colleagues or instructor recommended. You should think about the suggestions they’ve made and ensure that their suggestions will help you make the argument you want to make. You may decide to incorporate some suggestions and not others. When you treat writing as a process, it should become a genuine dialogue between you and your readers.

Publishing

Finally, you will submit your paper to an audience for review. As college students, this primarily means the paper that you turn in to your instructor for evaluation.

The preceding categories suggest that writing is a linear process—that is, that you will follow these steps in the following order:

prewriting→researching→outlining→drafting→revising→feedback→re-revising→publishing.The reality of the writing process, however, is that as you write you shuttle back and forth in these stages. For example, as you begin writing your thesis paragraph, the beginning of your essay, you will write and revise many times before you are satisfied with your opening; once you have a complete draft, you will more than likely return to the introduction to revise it again to better match the contents of the completed essay. This shuttling highlights the recursive nature of the writing process and can be diagrammed as follows:

prewriting↔researching↔outlining↔drafting↔revising↔feedback↔re-revising↔publishing.Furthermore, you should be aware that each writer has a unique writing process: some will be diligent outliners, while others may discover ideas as they write. There is no right way to write (so to speak), but the key is the notion of process—all strong writers engage in the writing process and recognize the importance of feedback and revision in the process.

Your Process

- Describe your writing process.

- Do you normally engage in the stages listed previously?

- If not, why? If so, what part of the process do you find most helpful?

- Share your process with the class to discover the variety in approaches writers take when writing.

1.5 Why Commit to the Writing Process?

In short, you should commit to the writing process because it’s the best known method for helping unconfident writers become confident writers. If there’s one thing that over fifty years of writing research has shown, it’s that students improve their writing skills through practice, practice, and more practice. The more you write in college, the more comfortable you will be with the conventions of academic and professional prose. When you commit to the process of writing, you will begin to understand that writing isn’t a rarefied talent available to a privileged few. You’ll begin to see that writing is a skill and can be developed through practice. What’s more, the writing process does not include the terrifying idea that you produce perfect prose on demand. Instead, you will learn to produce the best prose you can now and to improve it as you develop your ideas. This frees you up to concentrate on developing your skills of argument—skills that will be useful in whatever professional field you eventually work—rather than living in terror that you will make a mistake.

1.6 What Is Academic Argument?

Your Process

- When you hear the word “argument,” what other words come immediately to mind? Jot down as many related words as you can think of.

While scientists test their theories through experiments, literary scholars most often engage with their theories through academic argumentThe expression of knowledge in humanities disciplines, such as literature. Through academic argument, scholars present new ideas about literary works, challenge the ideas of other scholars, and model their interpretations of stories, novels, poems, plays, and other works.. When you think of the word “argument,” you probably think of conflict. Arguments are loud disagreements; arguments may involve yelling, cursing, or even, in extreme cases, physical violence. That’s not what we mean by academic argument, though. When scholars disagree, they don’t start throwing punches. Instead, academic argument looks more like a conversation. One scholar makes a claimA specific, debatable, and reasonable statement that interprets a work of literature. Because claims are always debatable, they must be supported with evidence. about a given text and cites evidenceFacts that support an author’s claims. In literary criticism, these facts comprise primarily quotations from literary texts; quotations from authoritative, scholarly sources; and historical documents. to support that claim. Another scholar might dispute that claim by making a counterclaimA specific, debatable, and reasonable statement that challenges, amends, or repurposes another scholar’s claim about a work of literature. and citing evidence that either challenges the original claim or supports the counterclaim. In an extended academic argument, more points of view emerge: the original scholar might respond or other scholars might intervene, offering claims of their own that support, modify, or challenge the original claims in the argument.

Let’s sketch out an example of an academic argument. First, review William Shakespeare’s famous “Sonnet 130”:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

I grant I never saw a goddess go:

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she, belied with false compare.William Shakespeare, “CXXX,” in Shakespeare’s Sonnets (1609; Project Gutenberg, 2010), http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1041.

We can imagine a critical argument centered on the speaker’s description of his lover. One scholar might claim that the poem is forward-thinking in its attitudes toward gender, refusing to employ the idealized rhetoric of most Renaissance love poetry, which characterized women purely by their adherence to physical standards of beauty. By insisting that his love can be “rare”—meaning here “valuable” or “unique”—even though her lips, hair, breasts, cheeks, breath, and voice do not match society’s expectations for exceptional beauty, this speaker implies that women are complex individuals, not static figures meant to satisfy men’s erotic desires.

Another scholar might disagree with this reading, pointing out that even though the poem refuses certain idealized comparisons (“Coral is far more red than her lips’ red”), it nonetheless dwells only on this woman’s physical features. This scholar might claim that the speaker’s refusal to employ common metaphors to describe his mistress only demonstrates his desire to show his superiority over other poets. The poem’s final line, which ends on “false compare,” says nothing about the woman, but instead insults the metaphors and similes of other poets whom this speaker sees as less talented than himself. The woman is given no name, no voice, and no personality—she is only described through what she is not.

These two critics disagree, but they express that disagreement through careful, reasoned prose. Indeed, they find some common ground: as the second scholar begins to respond, he or she admits that the poem does refuse idealized comparisons. Good academic argument is a give-and-take process, as each participant acknowledges the best points made by his or her interlocutors. The goal of academic argument is (usually) not to prove another scholar wrong, but instead to show how his or her argument could be expanded, supplemented, redirected, modified, or amended.

In this book, we will teach you how to engage in these conversations. Each chapter helps you develop your skills of engagement and will ask you to practice responding to the ideas of other scholars. Through repeated practice, you will learn how to bring these skills of academic argument into your class papers—to move beyond simply summarizing literary works and toward interpreting them. Each chapter also includes a sample paper from student writers so that you can see how your peers have applied both theoretical and rhetorical principles to craft effective academic arguments about a range of literary works and cultural topics.

Note

Our discussions of argument in this textbook largely follow the Toulmin method, which you can read more about in this writing guide provided by Colorado State University (http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/reading/toulmin).“Writing Guide: The Toulmin Method,” Colorado State University, http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/reading/toulmin. Our approach is also influenced by the refinements to Toulmin in the Little Red Schoolhouse (LRS) curriculum taught at the University of Chicago, the University of Virginia, and other institutions (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/welcome#3).“Little Red Schoolhouse Online,” University of Virginia Writing Program, http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/welcome. We have found Toulmin and LRS to be effective methods for beginning academic writers in a range of fields, including English literature.

In addition, we also follow the principles of nonthreatening argument that are presented by Carl Rogers. For more on Rogerian argument, review this article from Colorado State University (http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/co300man/com5e1.cfm) or Joseph M. Moxley’s article on the topic at Writing Commons (http://writingcommons.org/genres/academic-writing/rogerian-argument).Kate Kiefer, “What Is Rogerian Argument?,” Colorado State University, http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/co300man/com5e1.cfm; “Rogerian Argument: Solving Problems by Negotiating Differences,” Writing Commons (blog), 2012, http://writingcommons.org/genres/academic-writing/rogerian-argument.

1.7 Introducing an Academic Argument

In order to better understand the broad strokes of academic argument, we will read and analyze an undergraduate paper about Washington Irving’s short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, and the Spectre Bridegroom: From the “Sketch Book” (London: J. B. Lippincott, 1875; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 2000), http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=IrvLege.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1.

Your Process

-

As you work through this text, these process descriptions will make more sense if you’ve read the literary work under discussion. For this section, you should read Washington Irving’s short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Our discussion of student research and writing will reveal important plot details that you may want to discover on your own first. You can read this as an e-text provided by the University of Virginia (http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=IrvLege.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=1&division=div1).

You can also listen to a free audiobook of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” at Librivox (http://librivox.org/the-legend-of-sleepy-hollow-by-washington-irving).

Monica submitted this paper for an introductory literature class after the students read Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” during their unit on short fiction. Let’s look at her introduction first:

When one hears the title “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” a reader might shiver a little and think of the infamous spectre, “the apparition of a figure on horseback without a head … known, at all the country firesides, by the name of The Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow” (Irving 966). It is this legendary phantom that grants Washington Irving’s tale the label of ghost story. As such, readers would expect the legend to be overflowing with superstition and opposing forces—good vs. evil, known vs. unknown, supernatural vs. reality. “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is in fact meant to be a tale of opposing forces, but not in the same way as ghost story. It is a legend of rivalry, a rivalry between the characters Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt. Readers must understand that the opposing forces presented here are these two characters, the victim and the victor, the underdog and the front-runner—not those of supernatural and reality—in order to understand the true significance of Irving’s tale. Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt are meant to be more than just two characters with a rivalry—they are actually representations of the young American nation and its “motherland,” Great Britain. When these allegories are understood, and the true opposing forces are revealed, readers will finally be able to understand the ultimate message behind Irving’s tale—it is an allegory for the goals, the problems, and the livelihood of an adolescent America.

Your Process

After you finish Monica’s introduction, jot down the answer to these questions:

- How does this introduction entice you to read on? What lines grab your attention? Can you articulate why they do?

- Are any of the statements overly strong? “Must” we read the story in this particular way to understand it? Are there ways to tone down the language?

- What do you think will come next in this paper? You have just read “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”—are there details from the story that you think Monica will cite in the longer paper?

What makes Monica’s introduction so effective? Note first the way she summarizes one way that many readers interpret the story: “readers would expect the legend to be overflowing with superstition and opposing forces—good vs. evil, known vs. unknown, supernatural vs. reality.” In her argument, Monica will challenge this reading, but she does so subtly. “‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ is in fact meant to be a tale of opposing forces,” she writes, “but not in the same way as ghost story.” Monica establishes common ground with those who read the tale as a ghost story, noting that it “is…a tale of opposing forces.” By working from common ground toward a new understanding of the story, Monica follows the principles of argument laid out by Carl Rogers, a psychologist who insisted that effective argument is based not on conflict, but on compromise and negotiation between reader and writer.

However, a reader may sense that Monica is presenting her reading as the most authoritative or the best interpretation of the story, which can make a reader a bit defensive, especially if he or she does not necessarily agree with Monica’s claim. Notice the subtle revision (highlighted in bold) that makes the opening even more persuasive because it is less totalizing:

When one hears the title “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” a reader might shiver a little and think of the infamous spectre, “the apparition of a figure on horseback without a head … known, at all the country firesides, by the name of The Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow” (Irving 966). It is this legendary phantom that grants Washington Irving’s tale the label of ghost story. As such, readers would expect the legend to be overflowing with superstition and opposing forces—good vs. evil, known vs. unknown, supernatural vs. reality. “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” can be read as a tale of opposing forces, but not in the same way as ghost story. It is a legend of rivalry, a rivalry between the characters Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt. Readers may benefit by understanding that the opposing forces presented here are these two characters, the victim and the victor, the underdog and the front-runner—not those of supernatural and reality—in order to understand a major significance of Irving’s tale. Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt are meant to be more than just two characters with a rivalry—they are actually representations of the young American nation and its “motherland,” Great Britain. When these allegories are understood, and these opposing forces are revealed, readers will finally be able to understand a central message behind Irving’s tale—it is an allegory for the goals, the problems, and the livelihood of an adolescent America.

After establishing the common ground more subtly using the principles of nonthreatening argumentA philosophy of argument developed by Carl Rogers that is based on the notion that strong statements lead to strong responses, thus creating conflict and decreasing the effectiveness of the debate or argument., Monica then turns to her own ideas about the story: the tale, she insists, does focus on opposing forces, “but not in the same way as a ghost story” (our emphasis). Monica prepares the reader for her new claims about “Sleepy Hollow” by shifting her focus from the broad theme of opposition to the specific, nonsupernatural opposition of two characters’ rivalry. She writes, “It is a legend of rivalry, a rivalry between the characters Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt.” Monica introduces a fact from the story—a small piece of textual evidence—that doesn’t quite fit with the common view. Readers who have interpreted “Sleepy Hollow” through the lens of the ghost story want to read on and see how Monica’s focus on rivalry will change their view of Irving’s tale.

Illustration by John Quidor, The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane (1858).

Of course, most readers are skeptical: for each claim a writer makes, readers ask “So what?” Monica answers that “So what?” question by demonstrating a potential problem with her readers’ interpretations of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In the next sentence of her introduction, Monica shows her readers why her interpretation of the story is significant. “Readers must understand,” she writes, “that the opposing forces presented here are these two characters, the victim and the victor, the underdog and the front-runner—not those of supernatural and reality—in order to understand the true significance of Irving’s tale.” Effective introductions to literary interpretations focus on interpretive problems—not for the writer, but for the readers of the paper. Keep in mind that a literary interpretation may not seem significant to every person who reads it. Monica assumes, as you should assume when you write papers for your literature classes, that her readers care about literary works and want to understand them fully and well. For readers who do care about literature, however, the stakes Monica proposes are significant: readers who insist on interpreting “Sleepy Hollow” as a ghost story will miss the tale’s “true significance.”

Your Process

The University of Virginia provides a number of free modules to help college writers understand the parts of argument we discuss here. To better understand the parts of an effective introduction, you might work through the following modules:

- “Problem Frames Start Here”: http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=problem-frames/motivate/LRSintheWild.

- “Problem Frame Elements”: http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=problem-frames/frame/LRSintheWild.

- “State the Consequences of a Conceptual Problem by Answering ‘So What?’”: http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=problem-frames/consequences/LRSintheWild.

Once a writer introduces a problem, however, readers expect him or her to also propose a solution to that problem. The first big question readers are likely to ask a writer is, “What do you think?” In the final lines of her introduction, Monica tells her readers what she thinks about this story by making the central claim of her argument. Her claim explains what she believes to be the central opposition in Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”: “Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt are meant to be more than just two characters with a rivalry—they are actually representations of the young American nation and its ‘motherland,’ Great Britain. When these allegories are understood, and the true opposing forces are revealed, readers will finally be able to understand the ultimate message behind Irving’s tale—it is an allegory for the goals, the problems, and the livelihood of an adolescent America.” Monica offers a historicized reading of Irving’s tale (for more on historical theories about literature, see Chapter 7 "Writing about History and Culture from a New Historical Perspective"), arguing that the story’s true significance can be found by looking more closely at the time of the story’s composition, when America was an “adolescent” nation still at odds with Great Britain. Monica’s claim is specific, debatable, and significant (at least to readers who care about this story). In the body of her paper, Monica will unpack her claim, using subclaims and reasons to demonstrate to her readers why they should follow her interpretation of the story.

Your Process

- You can practice developing an effective subclaim using the module “Build Your Argument around a Significant Claim” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=claims/significant/LRSintheWild).

- Choose a literary work to analyze, preferably a short story or short lyric poem.

- Develop a working thesis that makes a claim about the work, knowing that this thesis claim may be revised.

- Create an informal outline that highlights the major stages of your argument—the evidence that you will use to support your thesis claim.

1.8 Student Writer at Work: Monica Platten’s “‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’: An Allegory for a Young America”

Now that we’ve reviewed Monica’s introduction in detail, you should read her entire paper. As you read, keep in mind the principles of argument we have already discussed.

Monica Platten

Professor Ryan Cordell

Introduction to Literature

December 17, 20–

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”: An Allegory for a Young America

When one hears the title “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” they might shiver a little and think of the infamous spectre, “the apparition of a figure on horseback without a head … known, at all the country firesides, by the name of The Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow” (Irving 966). It is this legendary phantom that grants Washington Irving’s tale the label of ghost story. As such, readers would expect the legend to be overflowing with superstition and opposing forces—good vs. evil, known vs. unknown, supernatural vs. reality. “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” can be read as a tale of opposing forces, but not in the same way as ghost story. It is a legend of rivalry, a rivalry between the characters Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt. Readers may benefit by understanding that the opposing forces presented here are these two characters, the victim and the victor, the underdog and the front-runner—not those of supernatural and reality—in order to understand a major significance of Irving’s tale. Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt are meant to be more than just two characters with a rivalry—they are actually representations of the young American nation and its “motherland,” Great Britain. When these allegories are understood, and these opposing forces are revealed, readers will finally be able to understand a central message behind Irving’s tale—it is an allegory for the goals, the problems, and the livelihood of an adolescent America.

The glen of Sleepy Hollow itself embodies the characteristics of the fresh, new land of America. It is a little valley in which “a small brook glides through [it], with just murmur enough to lull you to repose, and the occasional whistle of a quail, or the tapping of a woodpecker, is almost the only sound that ever breaks in upon the uniform tranquility” (956). This place is tranquil and beautiful, just as the new land of America was perceived by all who settled there. Not only is the beauty ample, but the natural resources are overflowing: there are “fat meadow lands, the rich fields of wheat, of rye, of buckwheat, and Indian corn, and the orchard burthened with ruddy fruit” (971); in this place “nature wore that rich and golden livery which we always associate with the idea of abundance” (976). Sleepy Hollow is a valley of bounty, a land of plenty. But like any other wild and largely uncharted territory, this land possesses an air of mystery. “A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land, and pervade the very atmosphere” (965), and any who dally long enough while passing through or decide to call the place home “begin to grow imaginative—to dream dreams, and see apparitions” (966). Likewise, the first settlers in America came as dreamers, searching for a new world, a new life, riches, and freedom.

Ichabod Crane is essential to this allegory of the new nation, because he is the representation of the American nation itself. The description of this character does not conform to one of a strong favorite, but to that of an underdog: “He was tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and leg, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, feet that might have served for shovels, and his whole fame most loosely hung together” (967). He is not a well-built man but an awkward one. As a schoolteacher he is intelligent, but does not hold a prestigious position in society; this reflects the rank of the new nation in a world order of countries. Nonetheless, he is optimistic and determined: “He had, however, a happy mixture of pliability and perseverance in his nature; he was in form and spirit like a supple jack—yielding, but tough; though he bent, he never broke; and though he bowed beneath the slightest pressure, yet, the moment it was away—jerk!—he was as erect, and carried his head as high as ever” (973). The personality of Ichabod Crane reflects the same qualities of the newly independent states of America—he is, like they are, an optimistic underdog.

The personality of Ichabod Crane also reflects the status of the American nation in his want for maturity. Crane, although a grown man, displays certain qualities of youth in his superstitious beliefs and his “his appetite for the marvelous, and his powers of digesting it, [which] were equally extraordinary” (969). These traits imply that he is still young and childish, not yet mature like an adult: “No tale was too gross or monstrous for his capacious swallow” (969). Nothing pleases him more than to “listen to marvellous tales of ghosts and goblins, and haunted fields and haunted brooks, and haunted bridges and haunted house, and particularly of the headless horseman” (969). Terence Martin breaks these ideas down: “By fitting the notion of gullibility into the dominant metaphor of Ichabod’s oral preoccupation, Irving emphasizes the childlike quality of his protagonist. Ichabod can swallow and digest anything; therefore he is always and increasingly gullible.… Irving couples the oral stage and imaginative indulgence; both signify childhood” (143). The young colonies of America are certainly lacking the wisdom and maturity of their relative, Great Britain; “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” published in 1820, just over 40 years after the Declaration of Independence, is set in “a remote period of American history, that is to say, some thirty year since” (Irving 967).

Martin agrees that “America … was a new nation which saw itself … [as] fresh and innocent” (137), but explains that it wanted to become an “adult” as quickly as possible, and therefore needed to stay away from child-like obsessions of fancy and the imagination. “A childish (primitive) society might legitimately take an interest in things imaginative; such a society, however, was precisely what America wanted not to be” (Martin 139). Washington Irving obviously shared this belief, because in the end of his tale, Crane’s excessive imagination leads to embarrassment and failure. This is, in a way, a warning for adolescent America. Martin concurs: “It would appear that for Irving there is no place, or a very limited place, for the hero of the imagination in the culture of early America. A nation of [Rips and] Ichabods, Americans might reason, would soon be no nation at all” (144).

Crane and the American nation have in common one more imperative attribute: ambition. This ambition is demonstrated in many ways. Just as the colonists of this new nation hungered for a better life, Ichabod Crane hungers: “In his devouring mind’s eye, he pictured to himself every roasting pig running about with a pudding in its belly, and an apple in its mouth; the pigeons were snugly put to bed in a comfortable pie, and tucked in with a coverlet of crust; the geese were swimming in their own gravy; and the ducks pairing cosily in dishes” (Irving 971). Delicious food is not the only luxury Crane hungers for; he longs for material possessions, too, such as land and the many animals that provide his scrumptious meals: “His heart yearned after the damsel who was to inherit these domains, and his imagination expanded with the idea, how they might be readily turned into cash, and the money invested in immense tracts of wild land, and shingle palaces in the wilderness.… He beheld himself bestriding a pacing mare, with a colt at her heel, setting out for Kentucky, Tennessee, or the Lord knows where”! (971).

This desire and ambition to possess and expand reflects the American initiative of Manifest Destiny. Crane is ambitious and confident that he is meant to fulfill these big plans: “He could not help, too, rolling his large eyes round him as he eat, and chuckling with the possibility that he might one day be lord of all this scene of almost unimaginable luxury and splendor” (977). Lloyd Daigrepont states that “Ichabod [also] represents the modern debasement of imagination by materialism, a pious utilitarianism, and the idea of progress, particularly as these were supported in early 19th-century America” (72) and goes so far as to call Crane himself “a representative of progress” (73). However, this ambition and desire for progress borders on greed. Crane is overly confident that he will one day acquire for himself the beautiful daughter and land of Baltus Van Tassel, a wealthy Dutch farmer. His motives for this possession are not supported by any reasons but personal desire. This same kind of greed and personal desire was demonstrated by the American states, as their motives for Manifest Destiny (although the particular term had not been coined quite yet) transformed from those of exploration and expansion to dominance and control over the native people and their land.

Brom Van Brunt, nicknamed appropriately Brom Bones, represents the strength of America’s motherland, Great Britain. He is a formidable man, “a burley, roaring, roystering blade … the hero of the country round, which rung with his feats of strength and hardihood” (Irving 972). He is powerful and skilled, always coming out on top: “He was famed for great knowledge and skill [in horsemanship] … he was foremost at all races and cockfights, and with the ascendancy which bodily strength always acquires in rustic life, was the umpire of all disputes” (972). This strength, knowledge, and skill—along with his competing interest in Katrina Van Tassel, the “apple” of Crane’s eye—makes him “the formidable rival with whom Ichabod Crane had to contend” (973). And although he is respected and admired—“The neighbours looked upon him with a mixture of awe, admiration, and good-will” (973)—he can be a bit of a bully, especially in said rivalry:

Ichabod became the object of whimsical persecution to Bones, and his gang of rough riders. They harried his hitherto peaceful domain; smoked out his singing school, by stopping up the chimney; broke in to the school-house at night, in spite of its formidable fastening of withe and window stakes, and turned everything topsy-turvy, so that the poor schoolmaster began to think all the witches in the country held their meetings there. But what was still more annoying, Brom took all opportunities of turning him into ridicule in the presence of his mistress, and had a scoundrel dog, whom he taught to whine in the most ludicrous manner, and introduced as a rival of Ichabod’s, to instruct her in psalmody. (974)

This list of grievances against Ichabod is reminiscent of the list of grievances claimed in the Declaration of Independence. Brom Bones is the powerful, respected rival of Crane, the slightly awkward underdog. And just as Great Britain used its power and strength to worry the colonies and then later the young American states, Brom uses his to harass Crane.

Katrina Van Tassel, daughter of the aforementioned Baltus Van Tassel, completes this allegory of an adolescent America because she is the prize, the treasure coveted by each nation—she represents power, honor, respect, and abundant resources. She is described as “blooming … plump as a partridge; ripe and melting and rosy cheeked as one of her father’s peaches, and universally famed” (970). The land of America is likewise copious in beauty, nature and wildlife abounding, the land is lush, fresh, and immense. People from all around the world would soon be immigrating to this new world in hopes of building a better life. “So tempting a morsel” (970) she was, yes, but also difficult to conquer: “Ichabod … had to win his way to the heart of a country coquette, beset with a labyrinth of whims and caprices, which were forever presenting new difficulties and impediments, and he had to encounter a host of fearful adversaries of real flesh and blood … keeping a watchful and angry eye upon each other” (972). Not only did many different countries and groups of people lust over the ample land, but this new world also created a struggle for power. Great Britain, the motherland, had been disowned by its young child. The American colonies decided to break away from this unfair and oppressive parent and start a life of their own, as a new nation. This budding nation, youthful and inexperienced as it was, found it necessary to work its way up in the world. This adolescent American had proved its ambition to be free, but now hoped to gain the respect of the world, power in the world order, pride in itself, and a sense of nationalism to infuse its people. Great Britain, however, was struggling to maintain its own pride and power after its defeat to the adolescent America; this once all-powerful empire wanted to uphold the respect it had earned throughout history. Which country would ultimately prove itself to be superior? This was the rivalry between the two nations. And that is the rivalry between Ichabod Crane and Brom Bones: who is the better man, who will win the girl and all her treasures, the respect, and the power?

While it appears clear that Irving’s tale is an allegory for a budding America and the rivalry between this underdog and its stronger, older relative Great Britain, some would disagree. Many critics, in fact, depict the rivalry as one between the regions and cultures in New England, and label Ichabod as the “threat,” or the bully. Donald Ringe boldly claims that “Ichabod Crane is clearly a Connecticut Yankee invading—and threatening—a New York Dutch society” (455). Following suit, Daniel Hoffman calls Brom Bones Irving’s “realistic Dutch frontiersman, who meets and bests a Yankee” (427). Their idea of Irving’s tale is summed up by Lloyd Daigrepont, who argues that “Brom is no musclebound bully, but rather a vigorous youth with a puckish spirit and a joyful exuberance for life” (75), who simply “wishes to rid Sleepy Hollow of the threat of Ichabod Crane” (76–77).

This claim that Brom Bones is the story’s hero and Crane the threatening force, while intriguing, seems misguided, especially as Irving himself described Bones as Crane’s “formidable rival” (973), as previously mentioned. In addition, Jeffrey Insko points out that Irving’s “body of work includes ‘serious’ histories (notably, biographies of George Washington and Christopher Columbus) and fictional sketches—among them ‘Rip Van Winkle’ and ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’—that are themselves deeply concerned with matters historiographical” (609). Regional conflicts in an adolescent America’s New England were much more recent and current for Irving’s time than conflicts between America and Great Britain. Levine and Krupat note these concerns: “There was a sense during the 1790s and early 1800s … that American nationalism was provisional, vulnerable, fragile. The War of 1812, which emerged from trade disputes with England, can therefore be seen as a war that, at least in part, spoke to Americans’ desires to put an end to such anxiety by in effect reenacting the American Revolution against England and winning a victory once and for all” (931). Although the rivalry between America and its overseas lineage was indeed current and ongoing, it extended a bit farther back into history. Before there could be conflict between regions of the American nation, it had to become a nation. The first major conflict was between America and Great Britain.

When readers understand that the rivalry in Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy of Hollow” is not only between the opposing forces of two characters, but also between an underdog and a powerful bully, then they can understand a central allegory of the story: an allegory of a young and developing America. Irving meant his tale to convey a warning to the budding nation: it is a reminder of its vulnerability, its problems, and the obstacles and hardships that stand in the way of its success. While Irving and other members of “the American literary nationalism of the 1820s … ultimately raised tough questions about the nation’s future, about its strengths and vulnerabilities, and about its character and potential as a democratic republic” (Levine and Krupat 934), these questions and criticisms, along with “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” are not without a sense of hope or optimism. Readers should remember that “Ichabod is not ultimately the loser in this legend. All he has lost is a farm girl’s love and a measure of self-respect; the former was no real passion, the latter can be repaired” (Hoffman 433–34). The American nation, like Ichabod, has the potential to succeed: to grow up, to learn from mistakes, and then to thrive against all odds.

Works Cited

Daigrepont, Lloyd. “Ichabod Crane: Inglorious Man of Letters.” Early American Literature 19.1 (1984): 68–81. JSTOR. Web. 15 Nov. 2010.

Hoffman, Daniel. “Irving’s Use of American Folklore in ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.’” PMLA 68.3 (1953): 425–35. JSTOR. Web. 9 Dec. 2010.

Insko, Jeffrey. “Diedrich Knickerbocker, Regular Bred Historian Early American.” Literature 43.3 (2008): 605–41. Project MUSE. Web. 11 Dec. 2010.

Irving, Washington. “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Norton Anthology of American Literature. Ed. Robert Levine and Arnold Krupat. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2007. 965–86. Print.

Levine, Robert, and Arnold Krupat, eds. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 7th ed., Vol. B. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2007. Print.

Martin, Terence. “Rip, Ichabod, and the American Imagination.” American Literature 31.2 (1959): 137–49. JSTOR. Web. 15 Nov. 2010.

Ringe, Donald. “New York and New England: Irving’s Criticism of American Society.” American Literature 38.4 (1967):455–67. JSTOR. Web. 9 Dec. 2010.

1.9 Understanding the Body of Monica’s Argument

Remember that the primary question readers ask of writers is “What do you think?” Because claims are specific and debatable, however, writers cannot simply state their claim. They must anticipate their readers’ new questions: “Why do you think that?” and “How do you know?” To explain why she thinks as she does about “Sleepy Hollow,” Monica begins each section of her paper with a subclaim, which is a specific, debatable statement that supports the global claim from the introduction. Let’s pull the subclaims out of the body of Monica’s paper so we can look at them more closely:

- SC1: “The glen of Sleepy Hollow itself embodies the characteristics of the fresh, new land of America.”

- SC2: “Ichabod Crane is essential to this allegory of the new nation, because he is the representation of the American nation itself. The description of this character does not conform to one of a strong favorite, but to that of an underdog.”

- SC3: “Brom Van Brunt, nicknamed appropriately Brom Bones, represents the strength of America’s motherland, Great Britain. He is a formidable man … powerful and skilled, always coming out on top.”

- SC4: “Katrina Van Tassel, daughter of the aforementioned Baltus Van Tassel, completes this allegory of an adolescent America because she is the prize, the treasure coveted by each nation—she represents power, honor, respect, and abundant resources.”

Each of these subclaims advances one aspect of the global claim, helping round out the ideas that Monica broaches in her introduction. Monica believes that Irving’s story “is an allegory for the goals, the problems, and the livelihood of an adolescent America” because “the description of [Ichabod] does not conform to one of a strong favorite, but to that of an underdog.” She also believes as she does because “Katrina Van Tassel…is the prize, the treasure coveted by each nation—she represents power, honor, respect, and abundant resources.” We could say the same thing about Monica’s other subclaims. None of these statements is self-evidently true; like the global claim in the paper’s introduction, the subclaims are debatable statements.

Your Process

- Do you sometimes struggle to move beyond your introduction and begin writing the body of an assigned paper? Do you struggle with organizing your thoughts over several pages? Jot down some thoughts about the elements of writing that you struggle with.

- You can practice developing effective reasons using the modules “Distinguish between Reasons and Evidence” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=reasons/dist/LRSintheWild) and “Choose a Parallel or Sequential Order for Your Reasons” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=reasons/ordering/LRSintheWild)

Now that Monica has answered her readers’ questions, “What do you think?” and “Why do you think that?” she must explain how she knows her ideas are true. To answer “How do you know?” Monica supports each of her subclaims with a range of evidence, both primary evidence (quotations from “Sleepy Hollow” itself) and secondary evidence (quotations from scholars writing about the story or its historical period). To demonstrate Ichabod’s “ambition,” for instance, Monica quotes from Irving’s story directly: “‘In his devouring mind’s eye, he pictured to himself every roasting pig running about with a pudding in its belly, and an apple in its mouth; the pigeons were snugly put to bed in a comfortable pie, and tucked in with a coverlet of crust; the geese were swimming in their own gravy; and the ducks pairing cosily in dishes’” (Irving 971). This textual evidence grounds Monica’s claims, helping readers see why she thinks what she thinks about Irving’s tale.

You should think carefully about how the evidence you quote supports the subclaims you make. While the connections between your claims and evidence may seem self-evident to you they may not be evident to your readers. Imagine, for instance, if a report came out saying students from a particular school were underperforming on their standardized tests. One person might see the report as evidence the school needs more funding. Another person might see the same report as evidence the school should be closed and its students sent elsewhere. Still another might see the report as evidence that the system of standardized testing doesn’t fairly evaluate students and should be changed. Readers interpret evidence in light of their social, political, religious, and cultural values and assumptions. Writing scholars call these underlying values and assumptions warrantsWarrants are the (often unspoken) values and assumptions that shape how readers understand evidence and the claims they believe that evidence will support. Warrants will be discussed later in the chapter.. When you use evidence, you should consider how different readers might interpret it, and if you foresee dramatic differences, you should carefully explain how you arrived at the connections you’ve drawn.

The following is one example that will show you how warrants provide the logical connection between claim and evidence. Most warrants are not directly stated but implied, which makes it useful for you to articulate your warrants so that you can concretely see the logical connection between claim and evidence:

Thesis Claim: “…Ichabod Crane and Brom Van Brunt are meant to be more than just two characters with a rivalry—they are actually representations of the young American nation and its ‘motherland,’ Great Britain. When these allegories are understood, and these opposing forces are revealed, readers will finally be able to understand a central message behind Irving’s tale—it is an allegory for the goals, the problems, and the livelihood of an adolescent America.”

- SC1: “The glen of Sleepy Hollow itself embodies the characteristics of the fresh, new land of America.”

- Warrant: The glen symbolizes the new America, which is central to the thesis since landscape, the geography, is essential to the allegory of Crane as representative of the new America.

In addition, Monica supplements her direct textual evidence in her paper with insights from other scholars, which also become counterclaims to her argument: “Lloyd Daigrepont states that ‘Ichabod [also] represents the modern debasement of imagination by materialism, a pious utilitarianism, and the idea of progress, particularly as these were supported in early 19th-century America’ and goes so far as to call Crane himself ‘a representative of progress’ (72, 73).” Secondary evidence grants authority to Monica’s argument, demonstrating that she has studied scholarly conversations around this work and is now engaging in those conversations in her own writing.

Your Process

- You can practice incorporating evidence into your writing using the modules “What Counts as Evidence” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=evidence/what-counts/LRSintheWild) and “Explain Your Evidence” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/evidence/explain/see-it).

The word “conversation” tells us quite a bit about why Monica’s argument works so well. She maintains a tone of engagement with other scholars throughout the paper, even when she disagrees with their ideas. In short, she answers yet another question readers are likely to ask of writers: “Have you considered this other point of view?” Note the way Monica explains potential objections to her argument, anticipating her readers’ skepticism about her argument.

While it appears clear that Irving’s tale is an allegory for a budding America and the rivalry between this underdog and its stronger, older relative Great Britain, some would disagree. Many critics, in fact, depict the rivalry as one between the regions and cultures in New England, and label Ichabod as the “threat,” or the bully. Donald Ringe boldly claims that “Ichabod Crane is clearly a Connecticut Yankee invading—and threatening—a New York Dutch society” (455). Following suit, Daniel Hoffman calls Brom Bones Irving’s “realistic Dutch frontiersman, who meets and bests a Yankee” (427). Their idea of Irving’s tale is summed up by Lloyd Daigrepont, who argues that “Brom is no musclebound bully, but rather a vigorous youth with a puckish spirit and a joyful exuberance for life,” who simply “wishes to rid Sleepy Hollow of the threat of Ichabod Crane” (75, 76–77).

As in her introduction, Monica outlines an alternative argument carefully and fairly. She quotes directly from scholars she disagrees with. Doing this doesn’t undermine the points Monica wants to make about “Sleepy Hollow.” Instead, by demonstrating her awareness of other possibilities, Monica demonstrates that her argument comes from close consideration of the story and many potential interpretations. Because Monica demonstrates her thorough research in the paragraph just quoted, her rebuttal of those opinions in the following paragraph has more force and authority.

This claim that Brom Bones is the story’s hero and Crane the threatening force, while intriguing, seems misguided, especially as Irving himself described Bones as Crane’s “formidable rival” (973), as previously mentioned. In addition, Jeffrey Insko points out that Irving’s “body of work includes ‘serious’ histories (notably, biographies of George Washington and Christopher Columbus) and fictional sketches—among them ‘Rip Van Winkle’ and ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’—that are themselves deeply concerned with matters historiographical” (609). Regional conflicts in an adolescent America’s New England were much more recent and current for Irving’s time than conflicts between America and Great Britain. Levine and Krupat note these concerns:

There was a sense during the 1790s and early 1800s … that American nationalism was provisional, vulnerable, fragile. The War of 1812, which emerged from trade disputes with England, can therefore be seen as a war that, at least in part, spoke to Americans’ desires to put an end to such anxiety by in effect reenacting the American Revolution against England and winning a victory once and for all. (931)

Although the rivalry between America and its overseas lineage was indeed current and ongoing, it extended a bit farther back into history. Before there could be conflict between regions of the American nation, it had to become a nation. The first major conflict was between America and Great Britain.

An effective academic writer considers multiple points of view in his or her writing. Such writers persuade their readers to follow their opinions about literature through carefully considered, well-organized claims, subclaims, and evidence.

Your Process

- You can practice responding to alternative points of view in your writing using the modules “Accommodate Alternative Points of View” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/AandR/alternatives/see-it) and “Respond to the Substance of Readers’ Objections” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/?q=AandR/objections/LRSintheWild).

1.10 Conclusion to the Introduction

As you write papers in your literature class (and indeed, in most of your college classes), keep the following questions in mind. Imagine your readers asking you such questions:

- What do you think about this story/poem/play/essay?

- Why do you think that?

- How do you know your ideas are right?

- Have you considered this or that alternative idea?

If you consistently answer these questions in your papers, you will develop your skills of academic argument. Remember, academic argument is not a battleground, and it’s not about yelling the loudest. Instead, academic argument is a conversation among people interested in the same topic.

What’s more, you do not have to convince everyone that your opinion is correct. For instance, you may not have been convinced by Monica’s argument about “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Perhaps there are essential details you noticed when reading the story that you feel Monica didn’t sufficiently address. Your disagreement doesn’t mean that Monica’s argument is invalid; by the same token, your disagreement doesn’t mean that your reading of the story is misguided. Instead of worrying about whose ideas are “correct,” you should instead think of such moments of disagreement as invitations to join the scholarly conversation surrounding a literary work. In this example, you could write your own argument that presents Monica’s ideas as the “common ground” that you would then respond to by making your own claims and subclaims and supporting them with the evidence you feel Monica overlooked.

There’s no single, “correct” interpretation for any work of literature. Of course, there are some interpretations that readers will find more persuasive than others. By learning about the different schools of literary theory presented in this book, you will hopefully learn to construct arguments about literature that many readers are more likely to find persuasive. In short, we will teach you how to engage in the conversations of academic argument.

1.11 End-of-Chapter Assessment

Key Takeaways

- Literary theories are intellectual tools that allow you to understand and explicate texts in a variety of ways. By learning different literary theories, you will become more confident in assessing novels, stories, poems, plays, and essays in class and beyond.

- Different schools of literary theory prioritize certain concerns for talking about literature while deemphasizing others: for example, readers’ responses, gender, sexuality, or race.

- Most skilled writers compose not in fits of inspiration but through the writing process, which includes the following steps: prewriting, researching, outlining, drafting, revising, seeking feedback, and re-revising.

- Literary scholars usually engage with their theories through academic argument; they make claims, support those claims with evidence, and respond directly to the ideas of other critics.

- You learned about the importance of the writing process, including peer review and the strategies for conducting peer review.

- You should think about writing as a dialogue between you, the writer, and your readers. Try to anticipate the questions they will have about your claims and respond to those questions directly in your argument.

Writing Exercises

- Freewriting exercise. You’ve probably heard the word “theory” before, perhaps in science classes. Spend ten minutes writing about how your understanding of literary theory developed as you read this chapter compared to your previous understanding of the word theory. What similarities do you see between literary theories and theories in other fields? What differences? Why do you think different fields all employ this word?

- Try to outline an argument you’ve had at some time in your life. For this exercise we don’t mean an academic argument. No, we mean an argument with a friend, sibling, parent, or maybe even a teacher! Think about that argument using the terms we introduced in this chapter. What claims did you make? What claims did your interlocutor make in response? Did either of you employ evidence? What kind of evidence? Can you create a diagram of the argument’s major elements? Once you’ve charted the argument, discuss it with your classmates. How do the elements of that “real” argument compare with the elements of academic argument you learned about in this chapter?

Instructor Supplement: Class Exercises

-

Students understand many of the basic principles of argument; they usually know when someone makes a persuasive case (during a conversation, say), and usually they know when someone’s case is weak (to put it crudely: they know when to call “BS!” on someone). They don’t usually think of these instincts as applicable to academic discourse. For this exercise, then, you will stage academic argument as a debate, which is a genre that even writing-phobic students often jump into with gusto. Divide the class into groups and then pose at least two broad, genuinely open questions about the work you’re reading in class (for instance, “Is Huckleberry Finn a racist novel?”).

Assign pairs of groups to debate each question, with one group arguing each side of the debate. Give each group fifteen minutes to prepare their “case” for the debate. Instruct each group to nominate a speaker. At the end of their time, groups must present their case in turn. The groups working on the other question(s) will vote to determine the debate “winner.” If you have time, you could also have a second round, giving each group five minutes to prepare rebuttals after each group has presented their initial arguments.

Finally, follow up on these debates by asking students to identify the parts of academic argument within the points they made during the debate. What claims did they make? What subclaims? What kinds of evidence did they use to support their claims? Did they respond to their opponents’ points or ignore them?

- During the latter half of this chapter, we referred students to the University of Virginia’s wonderful Little Red Schoolhouse Online (LRSO), a site that helps students learn the principles of effective academic argument. If you’re interested in incorporating LRSO more fully into your class, see the site’s overview of “Teaching with the Schoolhouse” (http://redschoolhouse.org/drupal/welcome#4).