This is “Literary Snapshot: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, section 1.1 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.1 Literary Snapshot: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

In the final chapter of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Alice attends the trial of the Knave of Hearts, who has been accused of stealing the Queen of Hearts’s tarts. You can read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass by accessing them at http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html and http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html.

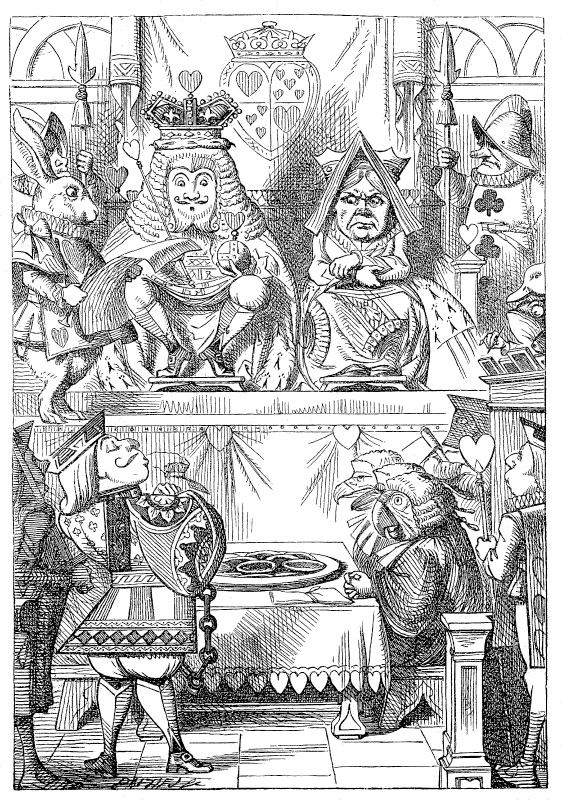

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

Read the following exchange, which takes place in the midst of that trial:

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. “Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?” he asked.

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:—

“They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

Don’t let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.”

“That’s the most important piece of evidence we’ve heard yet,” said the King, rubbing his hands; “so now let the jury—”

“If any one of them can explain it,” said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn’t a bit afraid of interrupting him), “I’ll give him sixpence. I don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it.”

The jury all wrote down on their slates, “She doesn’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it,” but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

“If there’s no meaning in it,” said the King, “that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any. And yet I don’t know,” he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; “I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. ‘—said I could not swim—’ you can’t swim, can you?” he added, turning to the Knave.Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. With Forty-Two Illustrations by John Tenniel (New York: D. Appleton, 1927; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1998), chap. 12, http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html.

Perhaps you’ve been in a literature classroom where you felt just like Alice: where it seemed like your teacher or your classmates could find meaning in stories, poems, and plays that you just couldn’t find. Perhaps you have even decided that you “don’t like English” because of such experiences. We hope with this book to help you rethink your approach to literary works so that you will find meaning in a wide range of texts.

This textbook aims to give you practical tools for approaching literary works that will ease some common anxieties that student readers feel in literature classrooms. This text will also show you how to apply those tools when you are asked to write literary analyses. We call those tools “literary theories.”

Your Process

- Have you ever wondered how your teachers or your classmates develop their ideas about literary works? Have you felt confused when reading stories, poems, plays, or essays, and unsure of how to begin interpreting them? Write a bit about your previous experiences in English classes.

- What does the word “theory” mean to you? Write your definition of the word.