This is “In a Set of Financial Statements, What Information Is Conveyed about Property and Equipment?”, chapter 10 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 10 In a Set of Financial Statements, What Information Is Conveyed about Property and Equipment?

Video Clip

(click to see video)In this video, Professor Joe Hoyle introduces the essential points covered in Chapter 10 "In a Set of Financial Statements, What Information Is Conveyed about Property and Equipment?".

10.1 The Reporting of Property and Equipment

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Recognize that tangible operating assets with lives of over one year (such as property and equipment) are initially reported at historical cost.

- Understand the rationale for assigning the cost of these operating assets to expense over time if the item has a finite life.

- Recognize that these assets are normally reported on the balance sheet at net book value, which is their cost less accumulated depreciation.

- Explain the reason for not reporting property and equipment at fair value except in certain specified circumstances.

Initially Reporting Property and Equipment at Historical Cost

Question: The retail giant Walmart owns thousands of huge outlets and supercenters located throughout the United States as well as in many foreign countries. These facilities contain a wide variety of machinery, fixtures, and the like such as cash registers and shelving. On its January 31, 2011, balance sheet, Walmart reports “property and equipment, net” of over $105 billion, a figure that made up almost 60 percent of the company’s total assets. This monetary amount was more than twice as large as any other asset reported by this business. Based on sheer size, the information conveyed about this group of accounts is extremely significant to any decision maker analyzing Walmart or another similar company. In creating financial statements, what is the underlying meaning of the monetary figure reported for property, equipment, and the like? What information is conveyed by the $105 billion balance disclosed by Walmart?

Answer: Four accounts make up the property and equipment reported by Walmart:

- Land

- Buildings and improvements

- Fixtures and equipment

- Transportation equipment

These are common titles, but a variety of other names are also used to report similar asset groups such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), fixed assets, and plant assets. Regardless of the name that is applied, the starting basis in reporting property, equipment, and any other tangible operating assets with a life of over one year is historical costAll the normal and necessary amounts incurred to get an asset into the position and condition to help generate revenues; it is the starting basis for the balance sheet presentation of assets such as inventory, land, and equipment..

This initial accounting is consistent with the recording process demonstrated previously for inventory. When available, accountants like historical cost because it is objective. Cost reflects the amount sacrificed to obtain land, machinery, buildings, furniture, and so forth. It can usually be determined when an arm’s length acquisition takes place: a willing buyer and a willing seller, both acting in their own self-interests, agree on an exchange price.

Thus, the cost incurred to obtain property and equipment provides information to decision makers about management policy and decision making. Cost indicates the amount management chose to sacrifice in order to gain the use of a specific asset. Unless the seller was forced to dispose of the property in a hurry (because of an urgent need for funds, as an example), cost is likely to approximate fair value when purchased. However, after the date of acquisition, the figure reported on the balance sheet will probably never again reflect the actual value of the asset.

Subsequently, for each of these operating assets that has a finite life (and most pieces of property and equipment other than land do have finite lives), the matching principle necessitates that the historical cost be allocated to expense over the anticipated years of service. This depreciationA mechanically derived pattern allocating the cost of long-lived assets such as buildings and equipment to expense over the expected number of years that they will be used by a company to help generate revenues. expense is recognized systematically each period as the company utilizes the asset to generate revenue.

For example, if equipment has a life of ten years, all (or most) of its cost is assigned to expense over that period. This accounting resembles the handling of a prepaid expense such as rent. The cost is first recorded as an asset and then moved to expense over time in some logical fashion as the utility is consumed. At any point, the reported net book value for the asset is the original cost less the portion of that amount that has been reclassified to expense. For example, Walmart actually reported property and equipment costing $148 billion but then disclosed that $43 billion of that figure had been moved to expense leaving the $105 billion net asset balance. As the future value becomes a past value, the asset account shrinks to reflect the cost reclassified to expense.

The Reporting of Accumulated Depreciation

Question: The basic accounting for property and equipment resembles that utilized for prepaid expenses such as rent and insurance. Do any significant differences exist between the method of reporting prepaid expenses and the handling of operating assets like machinery and equipment?

Answer: One important mechanical distinction does exist when comparing the accounting for prepayments and that used for property and equipment having a finite life. With a prepaid expense (such as rent), the asset is directly reduced over time as the cost is assigned to expense. Prepaid rent balances get smaller each day as the period of usage passes. This reclassification creates the rent expense reported on the income statement.

In accounting for property and equipment, the asset does not physically shrink. A seven-story building does not become a six-story building and then a five-story building. As the utility is consumed, buildings and equipment do not get smaller; they only get older. To reflect that reality, a separate accumulated depreciationA contra-asset account created to measure the cost of a depreciable asset (such as buildings and equipment) that has been assigned to expense to date. accountAs discussed in the coverage of accounts receivable and the allowance for doubtful accounts, an account that appears with another but as a direct reduction is known as a contra account. Accumulated depreciation is a contra account that decreases the reported cost of property and equipment to reflect the portion of that cost that has now be assigned to expense. is created to represent the total amount of the asset’s cost that has been reclassified to expense. Through this approach, information about the original cost continues to be available. For example, if equipment is reported as $30,000 and the related accumulated depreciation currently holds a balance of $10,000, the reader knows that the asset cost $30,000, but $10,000 of that amount has been expensed since the date of acquisition. If the asset has been used for two years to generate revenue, $6,000 might have been moved to expense in the first year and $4,000 in the second. The $20,000 net book valueOriginal cost of a depreciable asset such as buildings and equipment less the total amount of accumulated depreciation to date; it is also called net book value or carrying value. appearing on the balance sheet is the cost that has not yet been expensed because the asset still has future value.

As indicated previously, land does not have a finite life and, therefore, remains reported at historical cost with no assignment to expense and no accumulated depreciation balance.

Test Yourself

Question:

A company buys equipment for $100,000 with a ten-year life. Three years later, the company produces financial statements and prepares a balance sheet. The asset is not impaired in any way. What figure is reported for this equipment?

- The fair value on that date.

- The resale value at the end of the third year.

- $100,000 less the accumulated depreciation recorded for these three years.

- Fair value less accumulated depreciation for the most recent year.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice c: $100,000 less the accumulated depreciation recorded for these three years.

Explanation:

The historical cost ($100,000) serves as the beginning basis for the financial reporting of property and equipment. This monetary figure is then systematically transferred to expense over the life of the asset. The total amount of the expense recognized to date is recorded in an accumulated depreciation account. The book value to be shown on the balance sheet for this equipment is its historical cost less the accumulated depreciation to date.

Failure of Accounting to Reflect the Fair Value of Property and Equipment

Question: Walmart reports property and equipment with a net book value of $105 billion. However, that figure has virtually nothing to do with the value of these assets. They might actually be worth hundreds of billions. Decision makers analyze financial statements in order to make decisions about an organization at the current moment. Are these decision makers not more interested in the fair value of these assets than in what remains of historical cost? Why are property and equipment not reported at fair value? Is fair value not a much more useful piece of information than cost minus accumulated depreciation when assessing the financial health and prospects of a business?

Answer: The debate among accountants, company officials, investors, creditors, and others over whether various assets should be reported based on historical cost or fair value has raged for many years. There is no easy resolution. Good points can be made on each side of the argument. As financial accounting has evolved over the decades, rules for reporting certain assets (such as many types of stock and debt investments where exact market prices can be readily determined) have been changed to abandon historical cost in favor of reflecting fair value. However, no such radical changes in U.S. GAAP have taken place for property and equipment. Reporting has remained relatively unchanged for many decades. Unless the value of one of these assets has been impaired or it is going to be sold in the near future, historical cost less accumulated depreciation remains the basis for balance sheet presentation.

The fair value of property and equipment is a reporting alternative preferred by some decision makers, but only if the amount is objective and reliable. That is where the difficulty begins. Historical cost is both an objective and a reliable measure, determined through a transaction between a willing buyer and a willing seller. In contrast, any gathering of “experts” could assess the value of a large building or an acre of land at widely differing figures with equal certitude. No definitive value can possibly exist until sold. What is the informational benefit of a number that is so subjective? Furthermore, the asset’s value might change radically on a daily basis rendering previous assessments useless. For that reason, historical cost, as adjusted for accumulated depreciation, remains the accepted method for reporting property and equipment on an owner’s balance sheet.

Use of historical cost is supported by the going concern assumption that has long existed as part of the foundation of financial accounting. In simple terms, a long life is anticipated for virtually all organizations. Officials expect operations to continue for the years required to fulfill the goals that serve as the basis for their decisions. They do not plan to sell property and equipment prematurely but rather to utilize these assets for their entire lives. Consequently, financial statements are constructed assuming that the organization will function until all of its assets are consumed. Unless impaired or a sale is anticipated in the near future, the fair value of property and equipment is not truly of significance to the operations of a business. It might be interesting information but it is not directly relevant if no sale is contemplated.

However, the estimated fair value of a company’s property and equipment is a factor that does influence the current price of ownership shares traded actively on a stock exchange. For example, the price of shares of The Coca-Cola Company is certainly impacted by the perceived value of its property and equipment. A widely discussed calculation known as market capitalizationFigure computed by multiplying a company’s current stock price times the number of ownership shares outstanding in the hands of the public; it is used to gauge the fair value of a business as a whole. is one method used to gauge the fair value of a business as a whole. Market capitalization is determined by multiplying the current price of a company’s stock times the number of ownership shares outstanding. For example, approximately 2.3 billion shares of The Coca-Cola Company were in the hands of investors at December 31, 2010. Because the stock was selling for $65.77 per share on that day, the company’s market capitalization was about $151 billion. This figure does not provide a direct valuation for any specific asset but does give a general idea as to whether fair value approximates net book value or is radically different.

Talking with an Independent Auditor about International Financial Reporting Standards (Continued)

Following is a continuation of our interview with Robert A. Vallejo, partner with the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Question: In U.S. GAAP, land, buildings, and equipment have traditionally been reported at historical cost less the accumulated depreciation recognized to date. Adjustment to fair value is prohibited unless the asset’s value has been impaired. Because of the conservative nature of accounting, increases in value are ignored completely until proven through a disposal. Thus, land might be worth $20 million but only shown on the balance sheet as $400,000 if that amount reflects cost. According to IFRS, can increases in the fair value of these assets be reported?

Rob Vallejo: Under IFRS, a company can elect to account for all or specific types of assets using fair value. In that instance, the designated assets are valued each reporting period, adjusted up or down accordingly. Based on my experience working with companies reporting under IFRS, companies do not elect to account for fixed assets using fair value. This decision is primarily due to the administrative challenges of determining fair value each and every reporting period (quarterly for US listed companies) and the volatility that would be created by such a policy. Financial officers and the financial investors that follow their stocks rarely like to see such swings, especially those swings that cannot be predicted. However, in the right circumstances, using fair value might be a reasonable decision for some companies.

Key Takeaway

Land, buildings, and equipment are reported on a company’s balance sheet at net book value, which is historical cost less any portion of that figure that has been assigned to expense. Over time, the cost balance is not directly reduced. Instead, the expensed amount is maintained in a separate contra asset account known as accumulated depreciation. Thus, the asset’s cost remains readily apparent as well as net book value. Land and any other asset that does not have a finite life continue to be reported at cost. Unless the value of specific items has been impaired or an asset is to be sold in the near future, fair value is never used in reporting land, buildings, and equipment. It is not viewed as an objective or reliable amount. In addition, because such assets are usually not expected to be sold, fair value is of limited informational benefit to decision makers.

10.2 Determining Historical Cost and Depreciation Expense

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Make use of the guiding accounting rule to ascertain which costs are capitalized and which are expensed when acquiring property and equipment.

- List the variables that impact the amount of depreciation to be expensed each period in connection with the property and equipment owned by a company.

- Recognize that the straight-line method for assigning depreciation predominates in practice but any system that provides a rational approach can be used to create a pattern for this cost allocation.

Assets Classified as Property and Equipment

Question: Businesses hold numerous types of assets, such as receivables, inventory, cash, investments, and patents. Proper classification is important for the clarity of the reported information. In preparing a balance sheet, what requirements must be met for an asset to be included as part of a business’s property and equipment?

Answer: To be classified within the property and equipment category, an asset must have tangible physical substance and be expected to help generate revenues for longer than a single year. In addition, it must function within the normal operating activities of the business. However, it cannot be held for immediate resale, like inventory.

A building used as a warehouse and machinery operated in the production of inventory both meet these characteristics. Other examples include computers, furniture, fixtures, and equipment. Conversely, land acquired as a future plant site and a building held for speculative purposes are both classified as investments (or, possibly, “other assets”) rather than as property and equipment. Neither of these assets is being used at the current time to help generate operating revenues.

Determining Historical Cost

Question: The accounting basis for reporting property and equipment is historical cost. What amounts are included in determining the cost of such assets? Assume, for example, that Walmart purchases a parcel of land and then constructs a retail store on the site. Walmart also buys a new cash register to use at this outlet. Initially, such assets are reported at cost. For property and equipment, how is historical cost defined?

Answer: In the previous chapter, the cost of a company’s inventory was identified as the sum of all normal and necessary amounts paid to get the merchandise into condition and position to be sold. Property and equipment are not bought for resale, so this rule must be modified slightly. All expenditures are included within the cost of property and equipment if the amounts are normal and necessary to get the asset into condition and position to assist the company in generating revenues. That is the purpose of assets: to produce profits by helping to create the sale of goods and services.

Land can serve as an example. When purchased, the various normal and necessary expenditures made by the owner to ready the property for its intended use are capitalized to arrive at reported cost. These amounts include payments made to attain ownership as well as any fees required to obtain legal title. If the land is acquired as a building site, money spent for any needed grading and clearing is also included as a cost of the land rather than as a cost of the building or as an expense. These activities readied the land for its ultimate purpose.

Buildings, machinery, furniture, equipment and the like are all reported in a similar fashion. For example, the cost of constructing a retail store includes money spent for materials and labor as well as charges for permits and any fees paid to architects and engineers. These expenditures are all normal and necessary to get the structure into condition and position to help generate revenues.

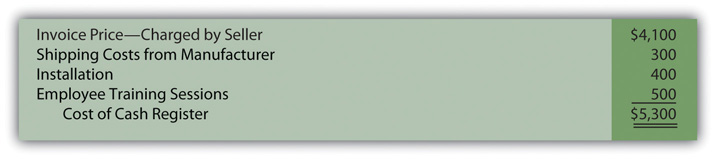

As another example, the cost of a new cash register might well include shipping charges, installation fees, and training sessions to teach employees to use the asset. These costs all meet the criterion for capitalization. They are normal and necessary payments to permit use of the equipment for its intended purpose. Hence, a new cash register bought at a price of $4,100 might actually be reported as an asset by its owner at $5,300 as follows:

Figure 10.1 Capitalized Cost of Equipment

Test Yourself

Question:

On January 1, Year One, a company buys a plot of land and proceeds to construct a warehouse on that spot. One specific cost of $10,000 was normal and necessary to the acquisition of the land. However, by accident, this charge was capitalized within the building account. Which of the following statements is not correct?

- The building account will always be overstated by $10,000.

- The land will be understated by $10,000 as long as the company owns it.

- For the next few years, net income will be understated.

- For the next few years, expenses will be overstated.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice a: The building account will always be overstated by $10,000.

Explanation:

A building has a finite life. During its use, the cost is systematically moved to expense. The $10,000 misstatement here overstates the building balance. However, the gradual expensing of that amount through depreciation reduces the overstatement over time. This error inflates the amount of expense reported each year understating net income. The land does not have a finite life. Therefore, its cost is not expensed, and the $10,000 understatement remains intact as long as the land is held.

Straight-Line Method of Determining Depreciation

Question: If a company pays $600,000 on January 1, Year One to rent a building to serve as a store for five years, a prepaid rent account (an asset) is established for that amount. Because the rented facility is used to generate revenues throughout this period, a portion of the cost is reclassified annually as expense to comply with the matching principle. At the end of Year One, $120,000 (or one-fifth) of the cost is moved from the asset balance into rent expense by means of an adjusting entry. Prepaid rent shown on the balance sheet drops to $480,000, the amount paid for the four remaining years. The same adjustment is required for each of the subsequent years as the time passes.

If, instead, the company buys a building with an expected five-year lifeThe estimated lives of property and equipment will vary widely. For example, in notes to its financial statements as of January 31, 2011, and for the year then ended, Walmart disclosed that the expected lives of its buildings and improvements ranged from three years to forty. for $600,000, the accounting is quite similar. The initial cost is capitalized to reflect the future economic benefit. Once again, at the end of each year, a portion of this cost is assigned to expense to satisfy the matching principle. This expense is referred to as depreciation. It is the cost of a long-lived asset that is recorded as expense each period. Should the Year One depreciation that is recognized in connection with this building also be $120,000 (one-fifth of the total cost)? How is the annual amount of depreciation expense determined for reporting purposes?

Answer: Depreciation is based on a mathematically derived system that allocates the asset’s cost to expense over the expected years of use. It does not mirror the actual loss of value over that period. The specific amount of depreciation expense recorded each year for buildings, machinery, furniture, and the like is determined using four variables:

- The historical cost of the asset

- Its expected useful life

- Any residual (or salvage) value anticipated at the end of the expected useful life

- An allocation pattern

After total cost is computed, officials estimate the useful life based on company experience with similar assets or on other sources of information such as guidelines provided by the manufacturer.As mentioned previously, land does not have a finite life and is, therefore, not subjected to the recording of depreciation expense. In a similar fashion, officials arrive at the expected residual value—an estimate of the likely worth of the asset at the end of its useful life. Both life expectancy and residual value can be no more than guesses.

To illustrate, assume a building is purchased by a company on January 1, Year One, for cash of $600,000. Based on experience with similar properties, officials believe that this structure will be worth only $30,000 at the end of an expected five-year life. U.S. GAAP does not require any specific computational method for determining the annual allocation of the asset’s cost to expense. Over fifty years ago, the Committee on Accounting Procedure (the authoritative body at the time) issued Accounting Research Bulletin 43, which stated that any method could be used to determine annual depreciation if it provided an expense in a “systematic and rational manner.” This guidance remains in effect today.

Consequently, a vast majority of reporting companies (including Walmart) have chosen to adopt the straight-line method to assign the cost of property and equipment to expense over their useful lives. The estimated residual value is subtracted from cost to arrive at the asset’s depreciable base. This figure is then expensed evenly over the expected life. It is systematic and rational. Straight-line depreciationMethod used to calculate the annual amount of depreciation expense by subtracting any estimated residual value from cost and then dividing this depreciable base by the asset’s estimated useful life; a majority of companies in the United States use this method for financial reporting purposes. allocates an equal expense to each period in which the asset is used to generate revenue.

Straight-line method:

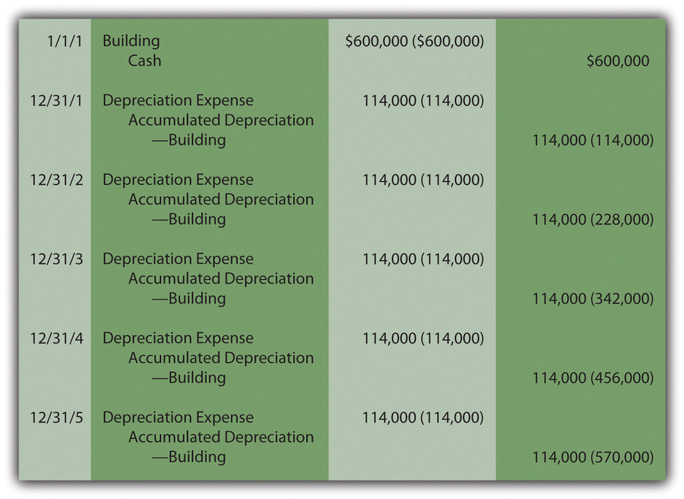

(cost – estimated residual value) = depreciable base depreciable base/expected useful life = annual depreciation ($600,000 – $30,000) = $570,000/5 years = depreciation expense of $114,000 per yearRecording Depreciation Expense

Question: An accountant determines depreciation for the current year based on the asset’s cost and estimated life and residual value. After depreciation has been calculated, how is this allocation of the asset’s cost to expense recorded within the company’s accounting system?

Answer: An adjusting entry is prepared at the end of each period to move the assigned cost from the asset account on the balance sheet to expense on the income statement. To reiterate, the building account is not directly reduced. A separate negative or contra account (accumulated depreciation) is created to reflect the total amount of the cost that has been expensed to date. Thus, the asset’s net book value as well as its original historical cost are both still in evidence.

The entries to record the cost of acquiring this building and the annual depreciation expense over the five-year life are shown in Figure 10.2 "Building Acquisition and Straight-Line Depreciation". The straight-line method is used here to determine each individual allocation to expense. Now that students are familiar with using debits and credits for recording, the number in parenthesis is included (where relevant to the discussion) to indicate the total account balance after the entry is posted. As has been indicated, revenues, expenses, and dividends are closed out each year. Thus, the depreciation expense reported on each income statement measures only the expense assigned to that period.

Figure 10.2 Building Acquisition and Straight-Line Depreciation

Because the straight-line method is applied, depreciation expense is a consistent $114,000 each year. As a result, the net book value reported on the balance sheet drops during the asset’s useful life from $600,000 to $30,000. At the end of the first year, it is $486,000 ($600,000 cost minus accumulated depreciation $114,000). At the end of the second year, net book value is reduced to $372,000 ($600,000 cost minus accumulated depreciation of $228,000). This pattern continues over the entire five years until the net book value equals the expected residual value of $30,000.

Test Yourself

Question:

On January 1, Year One, the Ramalda Corporation pays $600,000 for a piece of equipment that will produce widgets to be sold to the public. The company expects the asset to carry out this function for ten years and then be sold for $50,000. The straight-line method of depreciation is used. At the end of Year Two, company officials receive an offer to buy the equipment for $500,000. They reject this offer because they believe the asset is actually worth $525,000. What is the net reported balance for this equipment on the company’s balance sheet as of December 31, Year Two?

- $480,000

- $490,000

- $500,000

- $525,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: $490,000.

Explanation:

Unless the value of property or equipment is impaired or the asset will be sold in the near future, fair value is ignored. Cost is the reporting basis. This equipment has a depreciable base of $550,000 ($600,000 cost less $50,000 residual value). The asset is expected to generate revenues for ten years. Annual depreciation is $55,000 ($550,000/ten years). After two years, net book value is $490,000 ($600,000 cost less $55,000 and $55,000 or accumulated depreciation of $110,000).

Key Takeaway

Tangible operating assets with lives of over a year are initially reported at historical cost. All expenditures are capitalized if they are normal and necessary to put the property into the position and condition to assist the owner in generating revenue. If the asset has a finite life, this cost is then assigned to expense over the years of expected use by means of a systematic and rational pattern. Many companies apply the straight-line method, which assigns an equal amount of expense to every full year of use. In that approach, the expected residual value is subtracted from cost to get the depreciable base. This figure is allocated evenly over the anticipated years of use by the company.

10.3 Recording Depreciation Expense for a Partial Year

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Understand the need to record depreciation for each period of use even when property and equipment are disposed of prior to the end of the year.

- Construct the journal entry to record the disposal of property or equipment and the recognition of a gain or loss.

- Explain the half-year convention and the reason that it is frequently used by companies for reporting purposes.

Recording the Disposal of Property or Equipment

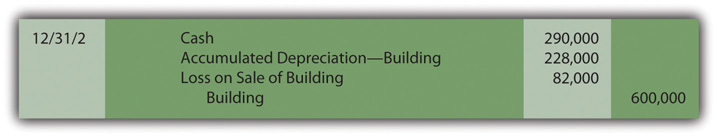

Question: Property and equipment are occasionally sold before the end of their estimated lives. A company’s operational needs might change or officials could want to gain the benefit of a newer or more efficient model. What accounting is necessary in the event that a piece of property or equipment is sold prior to the conclusion of its useful life? In the example illustrated in Figure 10.2 "Building Acquisition and Straight-Line Depreciation", assume that after the adjusting entry for depreciation is made on December 31, Year Two, the building is sold for $290,000 cash. How is that transaction recorded?

Answer: Accounting for the disposal of property and equipment is relatively straightforward.

First, to establish account balances that are appropriate as of the date of sale, depreciation is recorded for the period of use during the current year. In this way, the expense is matched with the revenues earned in the current period.

Second, the amount received from the sale is recorded while the net book value of the asset (both its cost and accumulated depreciation) is removed. If the owner receives less for the asset than net book value, a loss is recognized for the difference. If more is received than net book value, the excess is recorded as a gain so that net income increases.

Because the building is sold for $290,000 on December 31, Year Two, when the net book value is $372,000 (cost of $600,000 less accumulated depreciation of $228,000), a loss of $82,000 is reported by the seller ($372,000 net book value less $290,000 proceeds). The journal entry shown in Figure 10.3 "Sale of Building at a Loss" is recorded after the depreciation adjustment for the period is made.

Figure 10.3 Sale of Building at a Loss

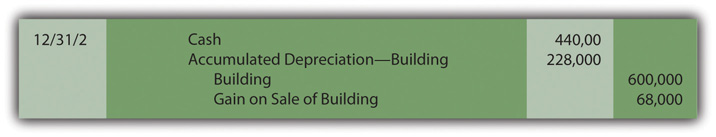

Conversely, if this building is sold on that same date for $440,000 rather than $290,000, the company receives $68,000 more than net book value ($440,000 less $372,000) so that a gain of that amount is recognized. The entry under this second possibility is presented in Figure 10.4 "Sale of Building at a Gain".

Figure 10.4 Sale of Building at a Gain

Although gains and losses such as these appear on the income statement, they are often shown separately from revenues and expenses. In that way, a decision maker can determine both the income derived from primary operations (revenues less expenses) and the amount that resulted from tangential activities such as the sale of a building or other property (gains less losses).

Test Yourself

Question:

The Lombardi Company buys equipment on January 1, Year One, for $2 million with an expected twenty-year life and a residual value of $100,000. Company officials apply the straight-line method to determine depreciation expense. On December 31, Year Three, this equipment is sold for $1.8 million. What gain is recognized on this sale?

- $10,000

- $85,000

- $100,000

- $185,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: $85,000.

Explanation:

The depreciable basis for this asset is $1.9 million ($2 million cost less $100,000 estimated residual value). This amount is to be expensed over twenty years at a rate of $95,000 per year ($1.9 million/20 years). After three years, accumulated depreciation is $285,000 ($95,000 × 3) so net book value is $1,715,000 ($2 million cost less $285,000 accumulated depreciation). The sale was for $1.8 million. The company reports a gain of $85,000 ($1.8 million received less $1,715,000 book value).

Recognizing Depreciation When Asset Is Used for a Partial Year

Question: In the previous reporting, the building was bought on January 1 and later sold on December 31 so that depreciation was always determined and recorded for a full year. However, in reality, virtually all such assets are bought and sold at some point within the year so that a partial period of use is more likely. What amount of depreciation is appropriate if property or equipment is held for less than twelve months during a year?

Answer: The recording of depreciation follows the matching principle. If an asset is owned for less than a full year, it does not help generate revenues for all twelve months. The amount of expense should be reduced accordingly. For example, if the building from the previous reporting is purchased on April 1, Year One, depreciation expense of only $85,500 (9/12 of the full-year amount of $114,000) is recognized on December 31, Year One. Similarly, if the asset is sold on a day other than December 31, less than a full year’s depreciation is assigned to expense in the year of sale. Revenue is not generated for the entire period; therefore, depreciation must also be recognized proportionally.

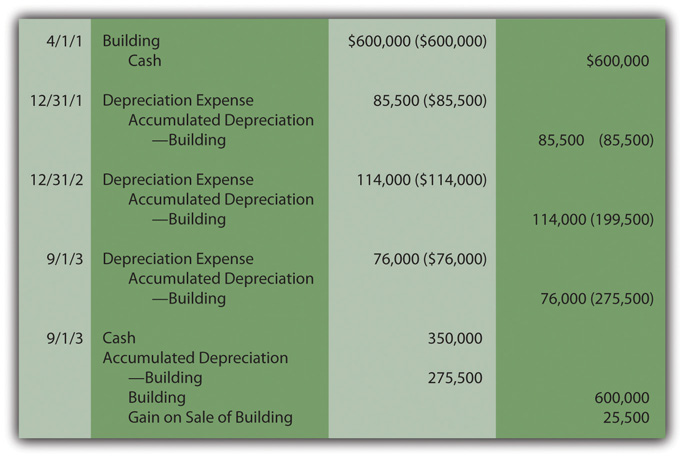

To illustrate, assume the building was purchased on April 1 of Year One for $600,000 and then sold for $350,000 on September 1 of Year Three. As just calculated, depreciation for Year One is $85,500 or 9/12 of the annual amount. In Year Three, depreciation for the final eight months that the property was used is $76,000 (8/12 of $114,000). The journal entries shown in Figure 10.5 "Acquisition, Depreciation, and Sale of Building" reduce the asset’s net book value to $324,500 (cost of $600,000 less accumulated depreciation of $275,500). Because cash of $350,000 is collected from the sale, a gain of $25,500 is recognized ($350,000 less $324,500).

Figure 10.5 Acquisition, Depreciation, and Sale of Building

The Half-Year Convention

Question: Monitoring the specific days on which depreciable assets are bought and sold seems like a tedious process. For example, what happens when equipment is bought on August 8 or when a building is sold on April 24? In practice, how do companies assign depreciation to expense when a piece of property or equipment is held for less than a full year?

Answer: Most companies hold a great many depreciable assets, often thousands. Depreciation is nothing more than a mechanical cost allocation process. It is not an attempt to mirror current value. Cost is mathematically assigned to expense in a systematic and rational manner. Consequently, company officials often prefer not to invest the time and effort needed to keep track of the specific number of days or weeks of an asset’s use during the years of purchase and sale.

As a result, depreciation can be calculated to the nearest month when one of these transactions is made. A full month of expense is recorded if an asset is held for fifteen days or more whereas no depreciation is recognized in a month where usage is less than fifteen days. No genuine informational value comes from calculating the depreciation of assets down to days, hours, and minutes. An automobile acquired on March 19, for example, is depreciated as if bought on April 1. A computer sold on November 11 is assumed to have been used until October 31.

As another accepted alternative, many companies apply the half-year conventionMethod of calculating depreciation for assets that are held for any period of time less than a year; automatically records one-half year of depreciation; it makes the maintenance of exact records as to the period of use unnecessary. (or some variation). When property or equipment is owned for any period less than a full year, a half year of depreciation is automatically assumed. The costly maintenance of exact records is not necessary. Long-lived assets are typically bought and sold at various times throughout each period so that, on the average, one-half year is a reasonable assumption. As long as such approaches are applied consistently, reported figures are viewed as fairly presented. Property and equipment bought on February 3 or sold on November 27 is depreciated for exactly one-half year in both situations.

Test Yourself

Question:

On August 12, Year One, the O’Connell Company buys a warehouse for $1.2 million with a ten-year expected life and an estimated residual value of $200,000. This building is eventually sold on March 18, Year Three, for $1,080,000 in cash. The straight-line method of depreciation is used for allocation purposes along with the half-year convention. What gain should O’Connell recognize on the sale of the warehouse?

- $80,000

- $84,000

- $108,000

- $120,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice a: $80,000.

Explanation:

Annual depreciation is $100,000: the depreciable basis of $1 million ($1.2 million less $200,000) allocated over ten years. Because the half-year convention is used, $50,000 is recorded in Years One and Three. The asset was used less than twelve months in each of these periods. When sold, accumulated depreciation is $200,000 ($50,000 + $100,000 + $50,000) and net book value is $1 million (cost was $1.2 million). Cash of $1,080,000 was received so that a gain of $80,000 must be recognized.

Key Takeaway

Depreciation expense is recorded for property and equipment at the end of each fiscal year and also at the time of an asset’s disposal. To record a disposal, cost and the accumulated depreciation as of that date are removed. Any proceeds are recorded and the difference between the amount received and the net book value surrendered is recognized as a gain (if more than net book value is collected) or a loss (if less is collected). Many companies automatically record depreciation for one-half year for any period of use of less than a full year. The process is much simpler and, as a mechanical allocation process, no need for absolute precision is warranted.

10.4 Alternative Depreciation Patterns and the Recording of a Wasting Asset

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the justification for accelerated methods of depreciation.

- Compute depreciation expense using the double-declining balance method.

- Realize that the overall impact on net income is not affected by a particular cost allocation pattern.

- Describe the units-of-production method, including its advantages and disadvantages.

- Explain the purpose and characteristics of MACRS.

- Compute depletion expense for a wasting asset such as an oil well or a forest of trees.

- Explain the reason that depletion amounts are not directly recorded as an expense.

Accelerated Depreciation

Question: Straight-line depreciation certainly qualifies as systematic and rational. The same amount of cost is assigned to expense during each period of an asset’s use. Because no specific method is required by U.S. GAAP, do companies ever use other approaches to create different allocation patterns for depreciation? If so, how are these methods justified?

Answer: The most common alternative to the straight-line method is accelerated depreciationAny method of determining depreciation that assigns larger expenses to the initial years of an asset’s service and smaller expenses to the later years; it is often justified by the assumption that newer assets generate more revenues than older assets do., which records a larger expense in the initial years of an asset’s service. The primary rationale for this pattern is that property and equipment frequently produce higher amounts of revenue earlier in their lives because they are newer. The matching principle would suggest that recognizing more depreciation in these periods is appropriate to better align the expense with the revenues earned.

A second justification for accelerated depreciation is that some types of property and equipment lose value more quickly in their first few years than they do in later years. Automobiles and other vehicles are a typical example of this pattern. Consequently, recording a greater expense in the initial years of use is said to better reflect reality.

Over the decades, a number of formulas have been invented to mathematically create an accelerated depreciation pattern—high expense at first with subsequent cost allocations falling each year throughout the life of the property. The most common is the double-declining balance method (DDB)A common accelerated depreciation method that computes expense each year by multiplying the asset’s net book value (cost less accumulated depreciation) times two divided by the expected useful life.. When using DDB, annual depreciation is determined by multiplying the current net book value of the asset times two divided by the expected years of life. As the net book value drops, the annual expense drops. This formula has no internal logic except that it creates the desired pattern, an expense that is higher in the first years of operation and less after that. Although residual value is not utilized in this computation, the final amount of depreciation recognized must be manipulated to arrive at this ending balance.

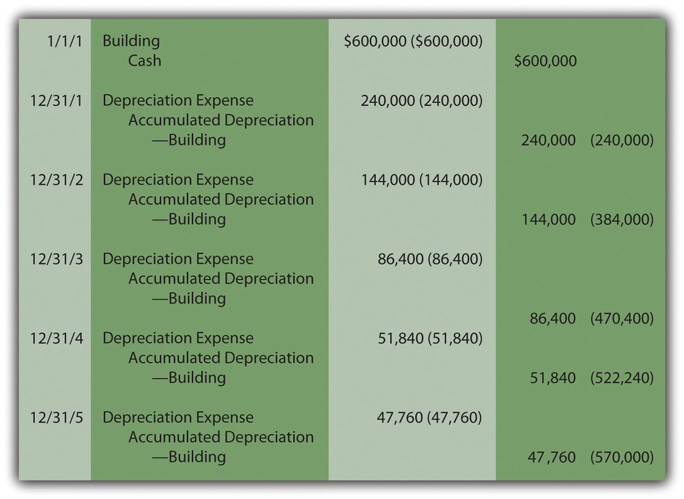

Depreciation for the building bought above for $600,000 with an expected five-year life and a residual value of $30,000 is calculated as follows if DDB is applied. Note how different this cost allocation pattern is than that shown in Figure 10.2 "Building Acquisition and Straight-Line Depreciation" using the straight-line method.

(cost – accumulated depreciation) × 2/expected life = depreciation expense for periodYear One:

($600,000 – $0) = $600,000 × 2/5 = $240,000 depreciation expenseYear Two:

($600,000 – $240,000) = $360,000 × 2/5 = $144,000 depreciation expenseYear Three:

($600,000 – $384,000) = $216,000 × 2/5 = $86,400 depreciation expenseYear Four:

($600,000 – $470,400) = $129,600 × 2/5 = $51,840 depreciation expenseYear Five:

($600,000 – $522,240) = $77,760,so depreciation for Year Five must be set at $47,760 to reduce the $77,760 net book value to the expected residual value of $30,000.

Note that the desired expense pattern for accelerated depreciation has resulted. The expense starts at $240,000 and becomes smaller in each subsequent period as can be seen in the adjusting entries prepared in Figure 10.6 "Building Acquisition and Double-Declining Balance Depreciation".

Figure 10.6 Building Acquisition and Double-Declining Balance Depreciation

When applying an accelerated depreciation method, net book value falls quickly at first because of the high initial expense levels. Thus, if an asset is sold early in its life, a reported gain is more likely (the amount received will be greater than this lower net book value). For example, in Figure 10.3 "Sale of Building at a Loss", the building was depreciated using the straight-line method and sold after two years for $290,000, creating a reported $82,000 loss because the net book value was $372,000. Net book value was high in comparison to the amount received.

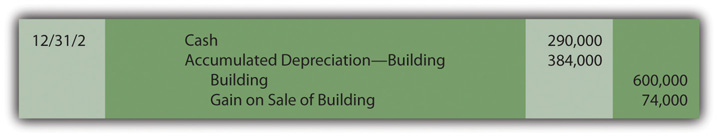

With DDB, the accumulated depreciation will be $384,000 after two years as shown in Figure 10.6 "Building Acquisition and Double-Declining Balance Depreciation". If the building is then sold on December 31, Year Two for $290,000, a $74,000 gain is reported because net book value has dropped all the way to $216,000 ($600,000 cost less $384,000 accumulated depreciation). Accelerated depreciation creates a lower net book value, especially in the early years of ownership.

Figure 10.7 Building Sold after Two Years—Double-Declining Balance Method Used

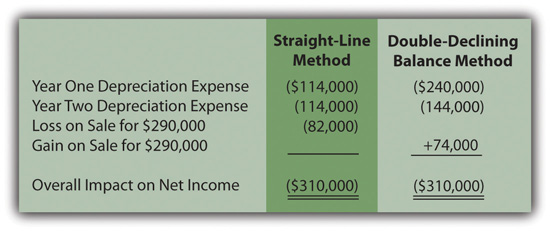

Although the annual amounts are quite different, the overall net income is never affected by the allocation pattern. In this example, a building was bought for $600,000 and later sold after two years for $290,000. Thus, net income for the entire period of use must be reduced by the $310,000 difference regardless of the approach applied.

Figure 10.8 Depreciation Methods—Overall Impact on Net Income

Test Yourself

Question:

On April 1, Year One, Hayden Corporation buys machinery for $30,000 and pays an additional $4,000 to have it delivered to its factory and then assembled. Company officials believe this machinery will last for ten years and then have a $2,000 remaining residual value. Depreciation is to be computed by applying the double-declining balance method. The half-year convention is utilized. The value of the asset actually declines at only a rate of 10 percent per year. On the company’s balance sheet as of December 31, Year Three, what is reported as the net book value for this asset?

- $18,432

- $18,496

- $19,584

- $25,500

Answer:

The correct answer is choice c: $19,584.

Explanation:

Cost of the asset is $34,000, which is multiplied by 2/10 to get $6,800. Because of the half-year convention, $6,800 is multiplied by 1/2. Depreciation is $3,400. For Year Two, book value is $30,600 ($34,000 less $3,400). When multiplied by 2/10, depreciation is $6,120. The contra account rises to $9,520 and book value falls to $24,480. When multiplied by 2/10, expense for the third year is $4,896. Accumulated depreciation is now $14,416 and book value is $19,584 ($34,000 less $14,416).

Units-Of-Production Method

Question: The two methods demonstrated so far for establishing a depreciation pattern are based on time, five years to be precise. In most cases, though, it is the physical use of the asset rather than the passage of time that is actually relevant to this process. Use is the action that generates revenues. How is the depreciation of a long-lived tangible asset determined if usage can be measured?

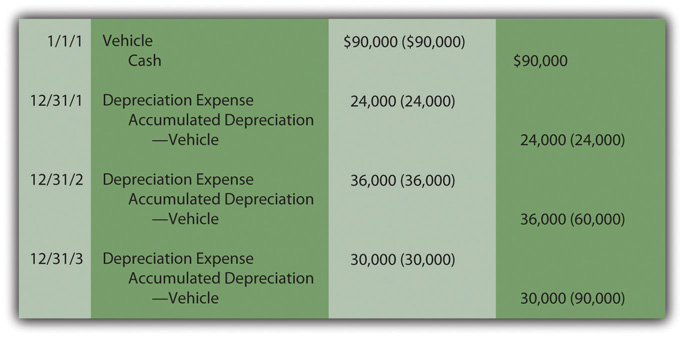

For example, assume that a limousine company buys a new vehicle for $90,000 to serve as an addition to its fleet. Company officials expect this limousine to be driven for 300,000 miles and then have no residual value. How is depreciation expense determined each period?

Answer: Depreciation does not have to be based on time; it only has to be computed in a systematic and rational manner. Thus, the units-of-production method (UOP)A method of determining depreciation that is not based on the passage of time but rather on the level of actual usage during the period. is another alternative that is occasionally encountered. UOP is justified because the periodic expense is matched with the work actually performed. In this illustration, the limousine’s depreciation is based on the total number of miles expected. Then, the annual expense is computed using the number of miles driven in a year, an easy figure to determine.

($90,000 less $0)/300,000 miles = $0.30 per mileDepreciation is recorded at a rate of $0.30 per mile. The depreciable cost basis is allocated evenly over the miles that the vehicle is expected to be driven. UOP is a straight-line method but one that is based on usage (miles driven, in this example) rather than years. Because of the direct connection between the expense allocation and the work performed, UOP is a very appealing approach. It truly mirrors the matching principle. Unfortunately, measuring the physical use of most assets is rarely as easy as with a limousine.

To illustrate, assume this vehicle is driven 80,000 miles in Year One, 120,000 miles in Year Two, and 100,000 miles in Year Three, depreciation will be $24,000, $36,000, and $30,000 when the $0.30 per mile rate is applied. The annual adjusting entries are shown in Figure 10.9 "Depreciation—Units-of-Production Method".

Figure 10.9 Depreciation—Units-of-Production Method

Estimations rarely prove to be precise reflections of reality. This vehicle will not likely be driven exactly 300,000 miles. If used for less and then retired, both the cost and accumulated depreciation are removed. A loss is recorded equal to the remaining net book value unless some cash or other asset is received. If driven more than the anticipated number of miles, depreciation stops at 300,000 miles. At that point, the cost of the asset will have been depreciated completely.

Although alternative methods such as the double-declining balance method and the units-of-production method are interesting theoretically, they are not very widely used in practice. Probably only about 5–10 percent of companies apply a method other than straight-line depreciation. However, as indicated later, accelerated depreciation is an important method when computing a company’s taxable income.

Test Yourself

Question:

On March 1, Year One, the Good Eating Company buys a machine to make donuts so that it can expand its menu. The donut maker cost the company $22,000 but has an expected residual value of $4,000. Officials believe this machine should be able to produce 100,000 dozen donuts over a ten-year period. In Year One, 7,000 dozen donuts are prepared and sold while in Year Two, another 11,000 dozen are made. However, the company is not satisfied with the profits made from selling donuts. Thus, on April 1, Year Three, after making 3,000 more dozen, the company sells the machine for $19,000 in cash. If the units-of-production method is used to compute depreciation, what gain or loss should the company recognize on the sale of the donut maker?

- Gain of $780

- Gain of $320

- Loss of $320

- Loss of $780

Answer:

The correct answer is choice a: Gain of $780.

Explanation:

The company expects to recognize an expense of $18,000 ($22,000 less $4,000) as it makes 100,000 dozen. That is $0.18 per dozen ($18,000/100,000 dozen). While being used, 21,000 dozen donuts are prepared (7,000 + 11,000 + 3,000). At $0.18 per dozen, total depreciation of $3,780 is recognized (21,000 dozen at $0.18 each). This expense reduces book value to $18,220 ($22,000 less $3,780). If sold for $19,000, the company reports a gain of $780 based on the excess received ($19,000 less $18,220).

MACRS

Question: Companies use straight-line depreciation, accelerated depreciation, or units-of-production depreciation for financial reporting. What method of determining depreciation is applied when a business files its federal income tax return? Can one of these methods be selected or is a specific approach required?

Answer: In most cases, the government wants businesses to buy more machinery, equipment, and the like because such purchases help stimulate the economy and create jobs. Consequently, for federal income tax purposes, companies are required to use a designed method known as Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). MACRS has several built-in tax incentives inserted to encourage businesses to acquire more depreciable assets. Greater depreciation expense is allowed, especially in the earlier years of use, so that the purchase reduces tax payments.

- Each depreciable asset must be placed into one of eight classes based upon its type and life. For example, a light truck goes into one class, but a typewriter is placed in another. Every asset within a class is depreciated by the same method and over the same life.

- For most of these classes, the number of years is relatively short so that the benefit of the expense is received quickly for tax purposes.

- Residual value is ignored completely. The entire cost can be expensed.

- For six of the eight classes, accelerated depreciation is required, which again creates more expense in the initial years.

Determining Depletion

Question: The cost of land is not depreciated because it does not have a finite life. However, land is often acquired solely for the natural resources that it might contain such as oil, timber, gold or the like. As the oil is pumped, the timber harvested or the gold extracted, a portion of the value is physically separated from the land. How is the reported cost of land affected when its natural resources are removed?

Answer: Oil, timber, gold, and the like are known as “wasting assets.” They are taken from land over time, a process referred to as depletionA method of allocating the cost of a wasting asset (such as a gold mine or an oil well) to expense over the periods during which the value is removed from the property.. Value is literally removed from the asset rather than being consumed through use as with the depreciation of property and equipment. The same mechanical calculation demonstrated above for the units-of-production (UOP) method is applied. The 2010 financial statements for Alpha Natural Resources state that “costs to obtain coal lands and leased mineral rights are capitalized and amortized to operations as depletion expense using the units-of-production method.”

Because the value is separated rather than used up, depletion initially leads to the recording of inventory (such as oil or gold, for example). An expense is recognized only at the eventual point of sale.

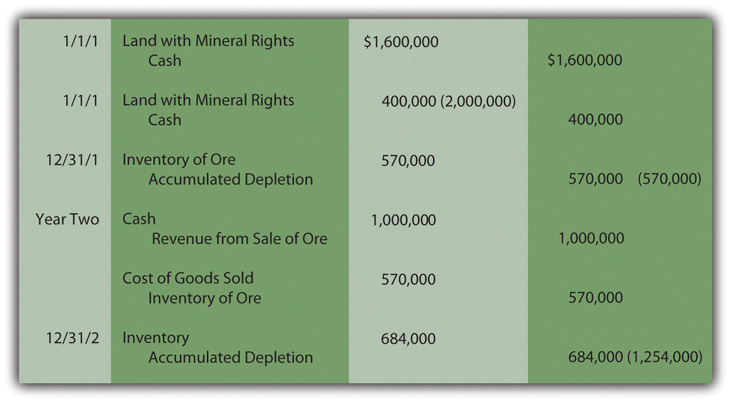

As with other types of property and equipment, historical cost is the sum of all normal and necessary expenditures to get the wasting asset into condition and position to generate revenues. To illustrate, assume that at the beginning of Year One, land is acquired for $1.6 million cash while another $400,000 is spent to construct a mining operation. Total cost is $2 million. The land is estimated to hold ten thousand tons of ore to be mined and sold. The land will be worth an estimated amount of only $100,000 after all ore is removed. Depletion is $190 per ton ([$2,000,000 cost less $100,000 residual value]/10,000 tons). It is a straight-line approach based on tons and not years, an allocation that follows the procedures of the units-of-production method.

Assume that 3,000 tons of ore are extracted in Year One and sold in Year Two for $1 million cash. Another 3,600 tons are removed in the second year for sale at a later time. Depletion is $570,000 in Year One ($190 × 3,000 tons) and $684,000 in Year Two ($190 × 3,600 tons). Note in Figure 10.10 "Depletion of Wasting Asset" that the ore is initially recorded as inventory and only moved to expense (cost of goods sold) when sold in the subsequent period. For depreciation, expense is recognized immediately as the asset’s utility is consumed. With depletion, no expense is recorded until the inventory is eventually sold.

Figure 10.10 Depletion of Wasting Asset

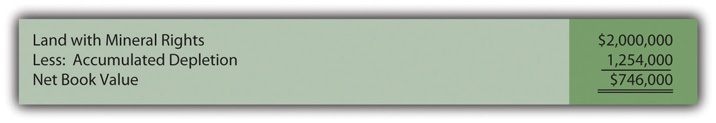

After two years, this land is reported on the company’s balance sheet at a net book value of $746,000 based on its historical cost of $2 million and accumulated depletion to date of $1,254,000 ($570,000 + $684,000). The remaining inventory of ore is reported as an asset at $684,000 because it has not yet been sold.

Figure 10.11 Net Book Value of Land with Mineral Rights After Depletion

Test Yourself

Question:

When crude oil is selling for $30 per barrel, the Ohio Oil Company buys an acre of land for $3.2 million because it believes that a reserve of oil lies under the ground. The company spends another $500,000 to set up the proper drilling apparatus. The company believes that 200,000 barrels of oil are in the ground at this location. Once the oil has been extracted, the land will have a resale value of only $100,000. In both Years One and Two, 70,000 barrels are pumped out but only 50,000 are sold in Year One and another 40,000 in Year Two. The price of crude oil stays steady in Year One but jumps to $39 per barrel during Year Two. What is the net book value of the land account at the end of Year Two?

- $1,080,000

- $1,180,000

- $1,740,000

- $2,340,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: $1,180,000.

Explanation:

The cost of this property is $3.7 million ($3.2 million plus $500,000). Expected residual value is $100,000 so $3.6 million will be the total depletion ($3.7 million minus $100,000). The land holds an estimated 200,000 barrels; thus, the depletion rate is $18 per barrel ($3.6 million/200,000 barrels). Over the two years, 140,000 barrels are extracted so that total depletion is $2.52 million ($18 × 140,000). Net book value is reduced to $1.18 million ($3.7 million less $2.52 million).

Key Takeaway

Additional cost allocation patterns for determining depreciation exist beyond the straight-line method. Accelerated depreciation records more expense in the earlier years of use than in later periods. This pattern is sometimes considered a better matching of expenses with revenues and closer to actual drops in value. The double-declining balance method is the most common version of accelerated depreciation. Its formula was designed to create the appropriate allocation pattern. The units-of-production method can be used for property and equipment where the quantity of work performed is easily monitored. This approach is also used in recording the depletion of wasting assets such as oil wells and silver mines. For federal income tax purposes, the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) is required. It provides certain benefits for the acquisition of depreciable assets as a way of encouraging more purchases to help the economy grow. For example, residual values are ignored and the expense is computed for most assets using accelerated depreciation methods.

10.5 Recording Asset Exchanges and Expenditures That Affect Older Assets

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Record the exchange of one asset for another and explain the rationale for this method of accounting.

- Explain when the fair value of an asset received must be used for recording an exchange rather than the fair value of the property surrendered.

- Compute the allocation of cost between assets when more than one is acquired in a single transaction.

- Determine which costs are capitalized when incurred in connection with an asset that has already been in use for some time and explain the impact on future depreciation expense calculations.

Exchanging One Asset for Another

Question: Some items are acquired by a company through an asset exchangeA trade of one asset for another in which the net book value of the old asset is removed from the records while the new asset is recorded at the fair value surrendered (if known); the difference between the recorded fair value and the previous net book value creates a gain or loss to be shown on the income statement. instead of as the result of a purchase. For example, the limousine discussed earlier might well be traded away after two years for a newer model. Such transactions are common, especially with vehicles. How is the historical cost of a new asset measured if obtained through an exchange rather than an acquisition?

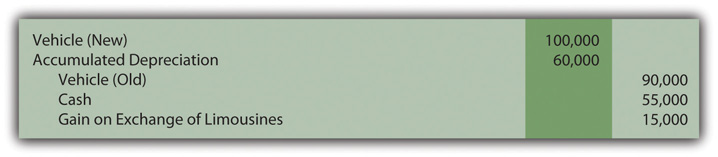

To illustrate, assume that this limousine is traded to an automobile manufacturer for a new model on December 31, Year Two. By that time, as shown in Figure 10.9 "Depreciation—Units-of-Production Method", the net book value had fallen to $30,000 (cost of $90,000 less accumulated depreciation of $60,000). However, because company employees have taken excellent care of the vehicle during its two years of use, its fair value is $45,000. As has been discussed, net book value rarely equals fair value during the life of property and equipment. Assume that the vehicle being acquired is worth $100,000 so the company also pays $55,000 in cash ($100,000 value received less $45,000 value surrendered) to complete the trade. How is such an exchange recorded?

Answer: In virtually all cases, fair value is the accounting basis used to record items received in an exchange. The net book value of the old asset is removed from the accounts and the new model is reported at fair value. Fair value is added; net book value is removed. A gain or loss is recognized for the difference.

In this example, the company surrenders two assets with a total fair value of $100,000 ($45,000 value for the old limousine plus $55,000 in cash) to obtain the new vehicle. However, the assets given up have a total net book value of only $85,000 ($30,000 and $55,000). A $15,000 gain is recognized on the exchange ($100,000 fair value less $85,000 net book value). The gain results because the old limousine had not lost as much value as the depreciation process had expensed. The net book value was reduced to $30,000 but the vehicle was worth $45,000.Accounting rules are created through a slow and meticulous process to avoid unintended consequences. For example, assume that Company A and Company B buy identical antique limousines for $30,000 that then appreciate in value to $100,000 because of their scarcity. Based solely on the accounting rule described in this section, if the two companies exchange these assets, each reports a gain of $70,000 while still retaining possession of an identical vehicle. This reporting is not appropriate because nothing has changed for either party. In reality, there was no gain since the companies retain the same financial position as before the trade. Thus, in creating the official guidance described previously, FASB held that an exchange must have commercial substance to justify using fair value. In simple terms, the asset acquired has to be different from the asset surrendered as demonstrated by the amount and timing of future cash flows. Without a difference, no rationale exists for making the exchange. If a trade does not have commercial substance, net book value is retained for the newly received asset and no gain is recognized. Based on the actual decline in value, too much expense had been recognized.

The journal entry to record this exchange of assets is presented in Figure 10.12 "Recording Exchange of Assets".

Figure 10.12 Recording Exchange of Assets

Determining the Fair Value to Record in an Exchange

Question: In the previous example, the value of the assets surrendered ($45,000 plus $55,000 or $100,000) equals the value of the new limousine received ($100,000). The trade was exactly even. Because one party might have better negotiating skills or a serious need for a quick trade, the two values can differ, at least slightly. For example, the limousine company could give up its old vehicle (worth $45,000) and cash ($55,000) and manage to convince the automobile manufacturer to hand over a new asset worth $110,000. If the values are not equal in an exchange, which fair value is used for reporting the newly acquired asset? Should the new limousine be recorded at the $100,000 value given up or the $110,000 value received?

Answer: To stay consistent with the historical cost principle, the new asset received in a trade is recorded at the fair value of the item or items surrendered. Giving up the previously owned property is the sacrifice made to obtain the new asset. That is the cost to the new buyer.

Generally, the fair value of the items sacrificed equals the fair value of the items received. Most exchanges involve properties of relatively equal worth; a value of $100,000 is surrendered to acquire a value of $100,000. However, that is not always the case. Thus, if known, the fair value of the assets given up always serves as the basis for recording the asset received. Only if the value of the property traded away cannot be readily determined is the new asset recorded at its own fair value.

Test Yourself

Question:

On January 1, Year One, a company spends $39,000 to buy a new piece of machinery with an expected residual value of $3,000 and a useful life of ten years. The straight-line method of depreciation is applied but not the half-year convention. On October 1, Year Three, the company wants to exchange this asset (which is now worth $31,000) for a new machine worth $40,000. To finalize the exchange, the company also pays cash of $9,000. What is the gain or loss on the trade?

- Loss of $600

- Loss of $1,100

- Gain of $1,300

- Gain of $1,900

Answer:

The correct answer is choice d: Gain of $1,900.

Explanation:

The new asset is recorded at $40,000 ($31,000 fair value + $9,000 cash). Depreciation has been $3,600 per year—cost less residual value ($39,000 − $3,000 or $36,000) over a ten-year life. Depreciation in Year Three is $2,700 (9/12 of $3,600). Accumulated depreciation is $9,900 ($3,600 + $3,600 + $2,700); book value is $29,100 ($39,000 less $9,900). If new asset is $40,000 and book value surrendered is $38,100 ($29,100 plus $9,000), the increase in financial position creates a gain of $1,900.

Allocating a Purchase Price between Two Assets

Question: Occasionally, two or more assets are bought for a single purchase price. The most common example is the acquisition of a building along with the land on which it sits. As has been discussed, the portion of the cost assigned to the building is depreciated to expense over its useful life in some systematic and rational manner. However, land does not have a finite life. Its cost remains an asset so that this portion of the price has no impact on reported net income over time. How does an accountant separate the amount paid for land from the cost assigned to a building when the two assets are purchased together?

Assume a business pays $5.0 million for three acres of land along with a five-story building. What part of this cost is attributed to the land and what part to the building? Does management not have a bias to assign more of the $5.0 million to land and less to the building to reduce the future amounts reported as depreciation expense?

Answer: Companies commonly purchase more than one asset at a time. This is sometimes referred to as a basket purchaseThe acquisition of more than one asset at a single cost; the cost is then allocated among those assets based on their relative values.. For example, a manufacturer might buy several machines in a single transaction. The cost assigned to each should be based on their relative values.

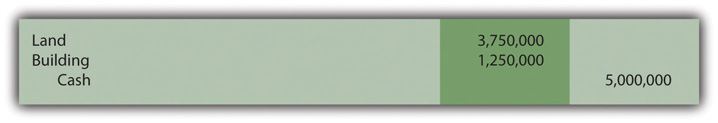

For this illustration, assume that the land and building bought for $5.0 million have been appraised at $4.5 million and $1.5 million, respectively, for a total of $6.0 million. Perhaps the owner needed cash immediately and was willing to accept a price of only $5.0 million. For the buyer, the land makes up 75 percent of the value received ($4.5 million/$6.0 million) and the building the remaining 25 percent ($1.5 million/$6.0 million). The cost is simply assigned in those same proportions: $3.75 million to the land ($5.0 million × 75 percent) and $1.25 million to the building ($5.0 million × 25 percent). This allocation enables the buyer to make the journal entry presented in Figure 10.13 "Allocation of Cost between Land and Building with Both Values Known".

Figure 10.13 Allocation of Cost between Land and Building with Both Values Known

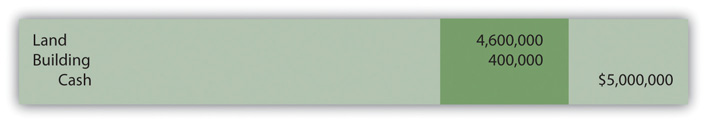

Occasionally, in a basket purchase, the value can be determined for one of the assets but not for all. As an example, the land might be worth $4.6 million, but no legitimate value is available for the building. Perhaps similar structures do not exist in this location for comparison purposes. In such cases, the known value is used for that asset with the remainder of the cost assigned to the other property. If the land is worth $4.6 million but no reasonable value can be ascribed to the building, the excess $400,000 ($5,000,000 cost less $4,600,000 assigned to the land) is arbitrarily assigned to the second asset.

Figure 10.14 Allocation of Cost Based on Known Value for Land Only

Does the possibility of bias exist in these allocations? Accounting is managed by human beings and they always face a variety of biases. That potential problem is one of the primary reasons that independent auditors play such an important role in the financial reporting process. These outside experts work to ensure that financial figures are presented fairly without bias. Obviously, if the buyer assigns more of the cost of a basket purchase to land, future depreciation will be less and reported net income higher. In contrast, if more of the cost is allocated to the building, depreciation expense is higher and taxable income and income tax payments are reduced. That is also a tempting choice.

Thus, the independent auditor gathers sufficient evidence to provide reasonable assurance that such allocations are based on reliable appraisal values so that both the land and the building figures are fairly presented. However, a decision maker is naïve not to realize that potential bias does exist in any reporting process.

Subsequent Expenditures for Property and Equipment

Question: Assume that the building discussed earlier is assigned a cost of $1,250,000 as shown in Figure 10.13 "Allocation of Cost between Land and Building with Both Values Known". Assume further that this asset has an expected life of twenty years and that straight-line depreciation is applied with no residual value. After eight years, accumulated depreciation is $500,000 ($1,250,000 × 8 years/20 years). At that point, when the building has a remaining life of 12 years, the owner spends an additional $150,000 on this asset. Should a later expenditure made in connection with a piece of property or equipment that is already in use be capitalized (added to the asset account) or expensed immediately?

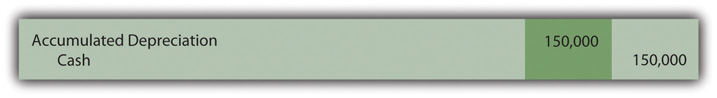

Answer: The answer to this question depends on the impact that this later expenditure has on the building. In many cases, additional money is spent simply to keep the asset operating with no change in expected life or improvement in future productivity. As shown in Figure 10.15 "Recording of Cost to Maintain or Repair Asset", such costs are recorded as maintenance expense if anticipated or repair expense if unexpected. For example, changing the oil in a truck at regular intervals is a maintenance expense whereas fixing a dent from an accident is a repair expense. However, this distinction has no impact on reported net income.

Figure 10.15 Recording of Cost to Maintain or Repair Asset

Other possibilities do exist. If the $150,000 expenditure increases the future operating capacity of the asset, the cost should be capitalized as shown in Figure 10.16 "Cost Capitalized Because of Increase in Operating Capacity". The building might have been made bigger, more efficient, more productive, or less expensive to operate. If the asset has been improved as a result of this expenditure, historical cost is raised.

Figure 10.16 Cost Capitalized Because of Increase in Operating Capacity

Assuming that no change in either the useful life of the building or its residual value occurs as a result of this work, depreciation expense will be $75,000 in each of the subsequent twelve years. The newly increased net book value is simply allocated over the useful life that remains.

($1,250,000 + $150,000 - $500,000)/12 remaining years = $75,000Another possibility does exist. The $150,000 might extend the building’s life without creating any other improvement. Because the building will now generate revenue for a longer period of time than previously expected, this cost is capitalized. A clear benefit has been gained from the amount spent. The asset is not physically bigger or improved but its estimated life has been extended. Consequently, the building is not increased directly, but instead, accumulated depreciation is reduced as shown in Figure 10.17 "Cost Capitalized Because Expected Life Is Extended". In effect, this expenditure has recaptured some of the previously expensed utility.

Figure 10.17 Cost Capitalized Because Expected Life Is Extended

Assuming that the $150,000 payment extends the remaining useful life of the building from twelve to eighteen years with no accompanying change in residual value, depreciation expense will be $50,000 in each of these remaining eighteen years. Once again, net book value has increased by $150,000 but, in this situation, the life of the asset has also been lengthened.

reduced accumulated depreciation: $500,000 - $150,000 = $350,000 adjusted net book value: $1,250,000 - $350,000 = $900,000 annual depreciation: $900,000/18 years = $50,000

Test Yourself

Question:

The Hatcher Company buys a building on January 1, Year One for $9 million. It has no anticipated residual value and should help generate revenues for thirty years. On December 31, Year Three, the company spends another $500,000 to cover the entire structure in a new type of plastic that will extend its useful life for an additional sixteen years. On December 31, Year Four, what will Hatcher report as accumulated depreciation for this building?

- $600,000

- $820,930

- $1,088,372

- $1,100,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice a: $600,000.

Explanation:

Annual depreciation is $300,000 ($9 million/30 years) or $900,000 after three years. The $500,000 expenditure reduces that balance to $400,000 because it extends the life (from twenty-seven years to forty-three) with no other increase in productivity. Book value is now $8.6 million ($9 million cost less $400,000 accumulated depreciation), which is allocated over forty-three years at a rate of $200,000 per year. Depreciation for Year Four raises accumulated depreciation from $400,000 to $600,000.

Key Takeaway

Assets are occasionally obtained through exchange. The reported cost for the new acquisition is based on the fair value of the property surrendered because that figure reflects the company’s sacrifice. The asset received is only recorded at its own fair value if the value of the asset given up cannot be determined. The difference between the net book value removed and the fair value recorded is recognized as a gain or loss. When more than one asset is acquired in a single transaction, the cost allocation is based on the relative fair values of the items received. Any subsequent costs incurred in connection with property and equipment are capitalized if the asset has been made bigger or better in some way or is just more efficient. If the length of the remaining useful life is extended, capitalization is established by reducing accumulated depreciation.

10.6 Reporting Land Improvements and Impairments in the Value of Property and Equipment

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Identify assets that qualify as land improvements and understand that the distinction between land and land improvements is not always clear.

- Perform the two tests used in financial accounting to determine the necessity of recognizing a loss because of an impairment in the value of a piece of property or equipment.

- Explain the theoretical justification for capitalizing interest incurred during the construction of property and equipment.

Recognition of Land Improvements

Question: Land is not subjected to the recording of depreciation expense because it has an infinite life. Often, though, a parking lot, fence, sidewalk, or the like will be attached to land. Those assets do have finite lives. How are attachments to land—such as a sidewalk—reported in financial accounting? Is that cost added to the land account or is some other reporting more appropriate? Should these assets be depreciated?

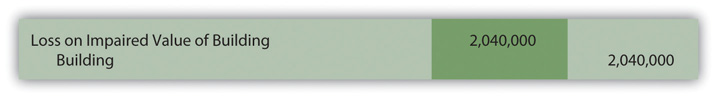

Answer: Any asset that is attached to land but has a finite life is recorded in a separate account, frequently referred to as land improvementsAssets attached to land with a finite life such as a parking lot or sidewalk.. This cost is then depreciated over the estimated life in the same way as equipment or machinery. The cost of a parking lot or sidewalk, for example, is capitalized and then reclassified to expense in a systematical and rational manner.