This is “Reporting Foreign Currency Balances”, section 7.5 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.5 Reporting Foreign Currency Balances

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Recognize that transactions denominated in a foreign currency have become extremely common.

- Understand the necessity of remeasuring the value of foreign currency balances into a company’s functional currency prior to the preparation of financial statements.

- Appreciate the problem that fluctuations in exchange rates cause when foreign currency balances are reported in a set of financial statements.

- Know which foreign currency balances are reported using a historical exchange rate and which balances are reported using the currency exchange rate in effect on the date of the balance sheet.

- Understand that gains and losses are reported on a company’s income statement when foreign currency balances are remeasured using current exchange rates.

Reporting Balances Denominated in a Foreign Currency

Question: In today’s global economy, many U.S. companies make a sizable portion of their sales internationally. The Coca-Cola Company, for example, generated 69.7 percent of its revenues in 2010 outside of the United States. For McDonald’s Corporation, foreign revenues were 66.4 percent of the reported total.

In such cases, U.S. dollars might still be the currency received. However, U.S. companies frequently make sales that will be settled in a foreign currency such as the Mexican peso or the Japanese yen. For example, a sale made today might call for the transfer of 20,000 pesos in two months. What reporting problems are created when a credit sale is denominated in a foreign currency?

Answer: This situation is a perfect example of why authoritative standards, such as U.S. GAAP, are so important in financial accounting. Foreign currency balances are common in today’s world. Although a company will have a functional currency in which it normally operates (probably the U.S. dollar for a U.S. company), transactions often involve a number of currencies. For many companies, sales, purchases, expenses, and the like can be denominated in dozens of different currencies. A company’s financial statements may report U.S. dollars because that is its functional currency, but underlying amounts to be paid or received might be set in another currency such as the euro or the pound. Mechanically, many methods of reporting such foreign balances have been developed, each with a significantly different type of impact.

Without standardization, a decision maker would likely face a daunting task trying to analyze similar companies if they employed different approaches for reporting foreign currency figures. Assessing the comparative financial health and future prospects of organizations that do not use the same accounting always poses a difficult challenge for investors and creditors. That problem would be especially serious if optional approaches were allowed in connection with foreign currencies. Therefore, U.S. GAAP has long had an authoritative standard for this reporting.

The basic problem with reporting foreign currency balances is that exchange rates are constantly in flux. The price of one euro in terms of U.S. dollars changes many times each day. If these rates remained constant, a single conversion value could be determined at the time of the initial transaction and then used consistently for reporting purposes. However, currency exchange rates are rarely fixed; they often change moment by moment. For example, if a sale is made on account by a U.S. company with the money to be received in a foreign currency in 60 days, the relative worth of that balance in terms of U.S. dollars will probably move up and down countless times before collection. Because such values float, the reporting of these foreign currency amounts poses a challenge with no easy resolution.

Accounting for Changes in Currency Exchange Rates

Question: Exchange rates that vary over time create a reporting problem for companies operating in international markets. To illustrate, assume a U.S. company makes a sale of a service to a Mexican company on December 9, Year One, for 100,000 Mexican pesos that will be paid at a later date. Assume also that the exchange rate on the day when the sale was made was 1 peso equal to $0.08. However, by the end of Year One when financial statements are produced, the exchange rate is different: 1 peso is now worth $0.09. What reporting does a U.S. company make of transactions that are denominated in a foreign currency if the exchange rate changes as time passes?As has been stated previously, this is an introductory textbook. Thus, a more in-depth examination of many important topics, such as foreign currency balances, can be found in upper-level accounting texts. The coverage here of foreign currency balances is only designed to introduce students to basic reporting problems and their resolutions.

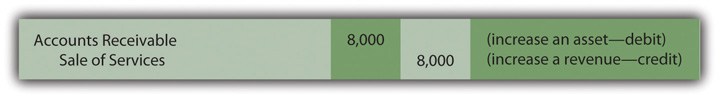

Answer: At the time of the sale, reporting is easy. The 100,000 pesos has an equivalent value of $8,000 (100,000 pesos × $0.08); thus, the journal entry in Figure 7.14 "Journal Entry—December 9, Year One—Sale of Services Made for 100,000 Pesos" is appropriate. Even though 100,000 pesos will be received, $8,000 is reported so that all balances on the seller’s financial statements are stated in terms of U.S. dollars.

Figure 7.14 Journal Entry—December 9, Year One—Sale of Services Made for 100,000 Pesos

By the end of the year, the exchange rate has changed so that 1 peso is equal to $0.09. The Mexican peso is worth a penny more in terms of the U.S. dollar. Thus, 100,000 pesos are more valuable and can now be exchanged for $9,000 (100,000 × $0.09). There are numerous reasons why the relative value of these two currencies might have changed, but the cause is not important from an accounting perspective.

When adjusting entries are prepared in connection with the production of financial statements at the end of Year One, one or both of the account balances (accounts receivable and sales of services) could remain at $8,000 or be updated to $9,000. The sale took place when the exchange rate was $0.08 but, now, before the money is collected, the peso has risen in value to $0.09. Accounting needs a standard rule as to whether the historical rate ($0.08) or the current rate ($0.09) is appropriate for reporting such foreign currency balances. Communication is difficult without that type of structure. Plus, the standard needs to be logical. It needs to make sense.

For over 25 years, U.S. GAAP has required that monetary assets and liabilitiesAmounts that are held by an organization as either cash or balances that will provide receipts or payments of a specified amount of cash in the future. denominated in a foreign currency be reported at the current exchange rate as of the balance sheet date. All other balances continue to be shown at the historical exchange rate in effect on the date of the original transaction. That is the approach that all organizations adhering to U.S. GAAP follow. Both the individuals who produce financial statements as well as the decision makers who use this information should understand the rule that is applied to resolve this reporting issue.

Monetary assets and liabilities are amounts currently held as cash or that will require a future transfer of a specified amount of cash. In the coverage here, for convenience, such monetary accounts will be limited to cash, receivables, and payables. Because these balances reflect current or future cash amounts, the current exchange rate is viewed as most relevant. In this illustration, the value of the receivable (a monetary asset) has changed in terms of U.S. dollars. The 100,000 pesos that will be collected have an equivalent value now of $0.09 each rather than $0.08. The reported receivable is updated to a value of $9,000 (100,000 pesos × $0.09).

Cash, receivables, and payables denominated in a foreign currency must be adjusted for reporting purposes whenever exchange rates fluctuate. All other account balances (equipment, sales, rent expense, dividends, and the like) reflect historical events and not future cash flows. Thus, they retain the rate in effect at the time of the original transaction and no further changes are ever needed. Because the sales figure is not a monetary asset or liability, the $8,000 balance continues to be reported regardless of the relative value of the peso.

The Income Effect of a Change in Currency Exchange Rates

Question: Changes in exchange rates affect the reporting of monetary assets and liabilities. Those amounts are literally worth more or less U.S. dollars as the relative value of the currency fluctuates over time. For the two balances above, the account receivable has to be remeasured on the date of the balance sheet because it is a monetary asset whereas the sales balance remains reported as $8,000 permanently. How is this change in the receivable accomplished? When monetary assets and liabilities denominated in a foreign currency are remeasured for reporting purposes, how is the increase or decrease in value reflected?

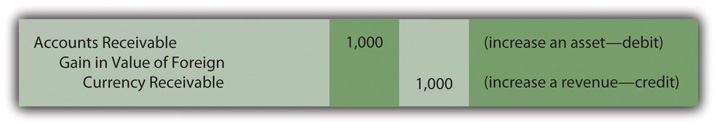

Answer: In this example, the value of the 100,000-peso receivable is raised from $8,000 to $9,000. When the amount reported for monetary assets and liabilities increases or decreases because of changes in currency exchange rates, a gain or loss is recognized on the income statement. Here, the reported receivable is now $1,000 higher. The company’s financial condition has improved and a gain is recognized. If the opposite occurs and the reported value of monetary assets declines (or the value of monetary liabilities increases), a loss is recognized. The adjusting entry shown in Figure 7.15 "Adjusting Entry at December 31, Year One—Remeasurement of 100,000 Pesos Receivable" is appropriate to reflect this change.

Figure 7.15 Adjusting Entry at December 31, Year One—Remeasurement of 100,000 Pesos Receivable

On its balance sheet, this company now reports a receivable as of December 31, Year One, of $9,000 while its income statement for that year shows sales revenue of $8,000 as well as the above gain of $1,000. Although the transaction was actually for 100,000 Mexican pesos, the company records these events in terms of its functional currency (the U.S. dollar) according to the provisions of U.S. GAAP.

Test Yourself

Question:

The Hamerstein Company is considering opening a retail store in Kyoto, Japan. In April of Year One, the company buys an acre of land in Kyoto by signing a note for ninety million Japanese yen to be paid in ten years. On that date, one yen can be exchanged for $0.012. By the end of Year One, one yen can be exchanged for $0.01. In connection with the company’s Year One financial statements, which of the following statements is not true?

- The company should report a loss because it held land during a time when the exchange rates changed.

- The company should report the note payable as $900,000 on its year-end balance sheet.

- The company should report the land as $1.08 million on its year-end balance sheet.

- The company should report a $180,000 gain because it held the note payable during this time.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice d: The company should report a $180,000 gain because it held the note payable during this time.

Explanation:

Because land is not a monetary account, it is initially recorded at $1.08 million (90 million yen × $0.012). That figure is never changed by future currency exchange rate fluctuations. Thus, no gain or loss is created by the land account. As a monetary account, the note payable is initially recorded at the same $1.08 million but is adjusted to $900,000 at the end of the year (90 million yen × $0.01). That $180,000 drop in the reported liability creates a reported gain of that amount.

Key Takeaway

Foreign currency balances are prevalent because many companies buy and sell products and services internationally. Although these transactions are frequently denominated in foreign currencies, they are reported in U.S. dollars when financial statements are produced for distribution in this country. Because exchange rates often change rapidly, many equivalent values could be calculated for these balances. According to U.S. GAAP, monetary assets and liabilities (cash as well as receivables and payables to be settled in cash) are updated for reporting purposes using the exchange rate at the current date. Changes in these balances create gains or losses to be recognized on the income statement. All other foreign currency balances (land, buildings, sales, expenses, and the like) continue to be shown at the historical exchange rate in effect at the time of the original transaction.