This is “Reporting a Balance Sheet and a Statement of Cash Flows”, section 3.4 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.4 Reporting a Balance Sheet and a Statement of Cash Flows

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- List the types of accounts presented on a balance sheet.

- Explain the difference between current assets and liabilities and noncurrent assets and liabilities.

- Calculate working capital and the current ratio.

- Provide the reason for a balance sheet to always balance.

- Identify the three sections of a statement of cash flows and explain the types of events included in each.

Information Reported on a Balance Sheet

Question: The third financial statement is the balance sheet. If a decision maker studies a company’s balance sheet (on its Web site, for example), what information can be discovered?

Answer: The primary purpose of a balance sheet is to report a company’s assets and liabilities at a particular point in time. The format is quite simple. All assets are listed first—usually in order of liquidityLiquidity refers to the ease with which assets can be converted into cash. Thus, cash is normally reported first followed by investments in stock that are expected to be sold soon, accounts receivable, inventory, and so on.—followed by all liabilities. A portrait is provided of each future economic benefit owned or controlled by the company (its assets) as well as its debts (liabilities).

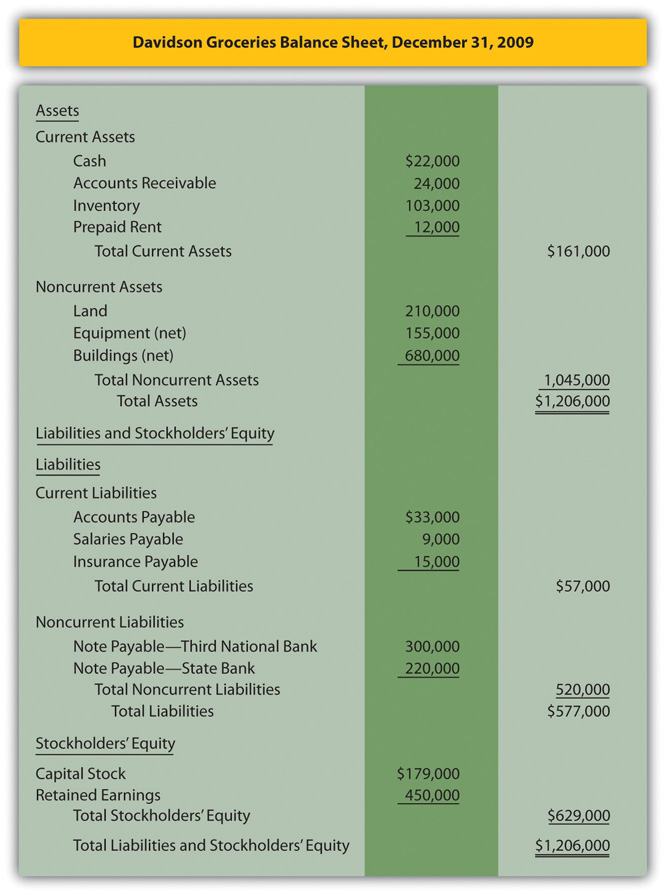

Figure 3.6 Balance SheetAs will be discussed in detail later in this textbook, noncurrent assets such as buildings and equipment are initially recorded at cost. This figure is then systematically reduced as the amount is moved gradually each period into an expense account over the life of the asset. Thus, balance sheet figures for these accounts are reported as “net” to show that only a portion of the original cost still remains recorded as an asset. This shift of the cost from asset to expense is known as depreciation and mirrors the using up of the utility of the property.

A typical balance sheet is reported in Figure 3.6 "Balance Sheet" for Davidson Groceries. Note that the assets are divided between current (those expected to be used or consumed within the following year) and noncurrent (those expected to remain with Davidson for longer than a year). Likewise, liabilities are split between current (to be paid during the upcoming year) and noncurrent (not to be paid until after the next year). This labeling is common and aids financial analysis. Davidson Groceries’ current liabilities ($57,000) can be subtracted from its current assets ($161,000) to arrive at a figure often studied by interested parties known as working capitalFormula measuring an organization’s liquidity (the ability to pay debts as they come due); calculated by subtracting current liabilities from current assets. ($104,000 in this example). It reflects short-term financial strength, the ability of a business or other organization to generate sufficient cash to pay debts as they come due.

Current assets can also be divided by current liabilities ($161,000/$57,000) to determine the company’s current ratioFormula measuring an organization’s liquidity (the ability to pay debts as they come due); calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities. (2.82 to 1.00), another figure calculated by many decision makers as a useful measure of short-term operating strength.

The balance sheet shows the company’s financial condition on one specific date. All of the other financial statements report events occurring over a period of time (often a year or a quarter). However, the balance sheet discloses all assets and liabilities as of the one specified point in time.

Test Yourself

Question:

Which of the following statements is true?

- Rent payable appears on a company’s income statement.

- Capital stock appears on a company’s balance sheet.

- Gain on the sale of equipment appears on a company’s balance sheet.

- Accounts receivable appears on a company’s income statement.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: Capital stock appears on a company’s balance sheet.

Explanation:

Assets and liabilities such as accounts receivable and rent payable are shown on a company’s balance sheet at a particular point in time. Revenues, expenses, gains, and losses are shown on an income statement for a specified period of time. Capital stock, a measure of the amount of net assets put into the business by its owners, is reported within stockholders’ equity on the balance sheet.

The Accounting Equation

Question: Considerable information is included on the balance sheet presented in Figure 3.6 "Balance Sheet". Assets such as cash, inventory, and land provide future economic benefits for the reporting entity. Liabilities for salaries, insurance, and the like reflect debts that are owed at the end of the fiscal period. The $179,000 capital stock figure indicates the amount of assets that the original owners contributed to the business. The retained earnings balance of $450,000 was computed earlier in Figure 3.4 "Statement of Retained Earnings" and identifies the portion of the net assets generated by the company’s own operations over the years. For convenience, a general term such as “stockholders’ equity” or “shareholders’ equity” usually encompasses the capital stock and the retained earnings balances.

Why does the balance sheet balance? This agreement cannot be an accident. The asset total of $1,206,000 is exactly the same as the liabilities ($577,000) plus the two stockholders’ equity accounts ($629,000—the total of capital stock and retained earnings). Thus, assets equal liabilities plus stockholders’ equity. What creates this monetary equilibrium?

Answer: The balance sheet will always balance unless a mistake is made. This is known as the accounting equationAssets = liabilities + stockholders’ equity. The equation balances because all assets must have a source: a liability, a contribution from an owner (contributed capital), or from operations (retained earnings)..

Accounting Equation (Version 1):

assets = liabilities + stockholders’ equity.Or, if the stockholders’ equity account is broken down into its component parts:

Accounting Equation (Version 2):

assets = liabilities + capital stock + retained earnings.As discussed previously, this equation stays in balance for one simple reason: assets must have a source. If a business or other organization has an increase in its total assets, that change can only be caused by (a) an increase in liabilities such as money being borrowed, (b) an increase in capital stock such as additional money being contributed by stockholders, or (c) an increase created by operations such as a sale that generates a rise in net income. No other increases occur.

One way to understand the accounting equation is that the left side (the assets) presents a picture of the future economic benefits that the reporting company holds. The right side provides information to show how those assets were derived (from liabilities, from investors, or from operations). Because no assets are held by a company without a source, the equation (and, hence, the balance sheet) must balance.

Accounting Equation (Version 3):

assets = the total source of those assets.The Statement of Cash Flows

Question: The fourth and final financial statement is the statement of cash flows. Cash is so important to an organization and its financial health that a complete statement is devoted to presenting the changes that took place in this one asset. As can be inferred from the title, this statement provides a portrait of the various ways the reporting company generated cash during the year and the uses that were made of it. How is the statement of cash flows structured?

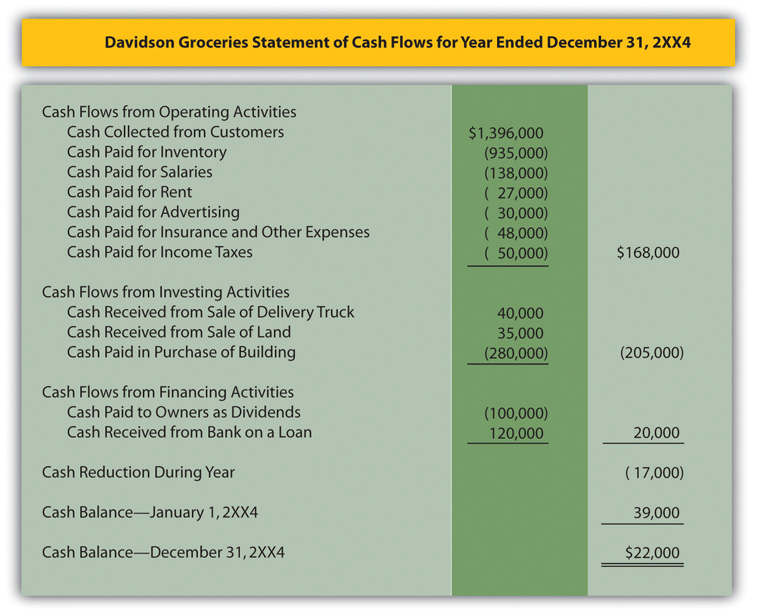

Answer: Decision makers place considerable emphasis on a company’s ability to generate significant cash inflows and then make wise use of that money. Figure 3.7 "Statement of Cash Flows" presents an example of that information in a statement of cash flows for Davidson Groceries for the year ended December 31, 2XX4. Note that all the cash changes are divided into three specific sections:

- Operating activitiesA statement of cash flow category relating to cash receipts and disbursements arising from the primary activities of the organization.

- Investing activitiesA statement of cash flow category relating to cash receipts and disbursements arising from an asset transaction other than one related to the primary activities of the organization.

- Financing activitiesA statement of cash flow category relating to cash receipts and disbursements arising from a liability or stockholders’ equity transaction other than one related to the primary activities of the organization.

Figure 3.7 Statement of Cash FlowsThe cash flows resulting from operating activities are being shown here using the direct method, an approach recommended by the FASB. This format shows the actual amount of cash flows created by individual operating activities such as sales to customers and purchases of inventory. In the business world, an alternative known as the indirect method is more commonly encountered. This indirect method will be demonstrated in detail in Chapter 17 "In a Set of Financial Statements, What Information Is Conveyed by the Statement of Cash Flows?".

Classification of Cash Flows

Question: In studying the statement of cash flows, a company’s individual cash flows relating to selling inventory, advertising, selling land, buying a building, paying dividends and the like can be readily understood. For example, when the statement indicates that $120,000 was the “cash received from bank on a loan,” a decision maker should have a clear picture of what happened. There is no mystery.

All cash flows are divided into one of the three categories:

- Operating activities

- Investing activities

- Financing activities

How are these distinctions drawn? On a statement of cash flows, what is the difference in an operating activity, an investing activity, and a financing activity?

Answer: Cash flows listed as the result of operating activities relate to receipts and disbursements that arose in connection with the central activity of the organization. For Davidson Groceries, these cash changes were created by daily operations and include selling goods to customers, buying merchandise, paying salaries to employees, and the like. This section of the statement shows how much cash the primary business function generated during this period of time, a figure that is watched closely by virtually all financial analysts. Ultimately, a business is only worth the cash that it can create from its normal operations.

Investing activities report cash flows created by events that (1) are separate from the central or daily operations of the business and (2) involve an asset. Thus, the amount of cash collected when either equipment or land is sold is reported within this section. A convenience store does not participate in such transactions as a regular part of operations and both deal with an asset. Cash paid to buy a building or machinery will also be disclosed in this same category. Such purchases do not happen on a daily operating basis and an asset is involved.

Like investing activities, the third section of this statement—cash flows from financing activities—is unrelated to daily business operations but, here, the transactions relate to either a liability or a stockholders’ equity balance. Borrowing money from a bank meets these criteria as does distributing a dividend to shareholders. Issuing stock to new owners for cash is another financing activity as is payment of a noncurrent liability.

Any decision maker can study the cash flows of a business within these three separate sections to receive a picture of how company officials managed to generate cash during the period and what use was made of it.

Test Yourself

Question:

In reviewing a statement of cash flows, which one of the following statements is not true?

- Cash paid for rent is reported as an operating activity.

- Cash contributed to the business by an owner is an investing activity.

- Cash paid on a long-term note payable is a financing activity.

- Cash received from the sale of inventory is an operating activity.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: Cash contributed to the business by an owner is an investing activity.

Explanation:

Cash transactions such as the payment of rent or the sale of inventory that are incurred as part of daily operations are included within operating activities. Events that do not take place as part of daily operations are either investing or financing activities. Investing activities are carried out in connection with an asset such as a building or land. Financing activities impact either a liability (such as a note payable) or a stockholders’ equity account (such as contributed capital).

Key Takeaway

The balance sheet is the only one of the four financial statements that is created for a specific point in time. It reports the company’s assets as well as the source of those assets: liabilities, capital stock, and retained earnings. Assets and liabilities are divided between current and noncurrent. This classification system permits the reporting company’s working capital and current ratio to be computed for analysis purposes. The statement of cash flows explains how the cash balance changed during the year. All cash transactions are classified as falling within operating activities (daily activities), investing activities (nonoperating activities that affect an asset), or financing activities (nonoperating activities that affect either a liability or a stockholders’ equity account).

Talking with a Real Investing Pro (Continued)

Following is a continuation of our interview with Kevin G. Burns.

Question: Warren Buffett is one of the most celebrated investors in history and ranks high on any list of the richest people in the world. When asked how he became so successful at investing, Buffett answered quite simply: “We read hundreds and hundreds of annual reports every year.”See http://www.minterest.com/warren-buffet-quotes-quotations-on-investing/.

Annual reports, as you well know, are the documents that companies produce each year containing their latest financial statements. You are an investor yourself, one who provides expert investment analysis for your clients. What is your opinion of Mr. Buffett’s advice?

Kevin Burns: Warren Buffet—who is much richer and smarter than I am—is correct about the importance of annual reports. Once you get past the artwork and the slick photographs and into the “meat” of these reports, the financial statements are a treasure trove of information. Are sales going up or down? Are expenses (such as cost of goods sold) increasing or decreasing as a percentage of sales? Is the company making money? How much cash is the business generating? How are the officers compensated? Do they own stock in the company?

I actually worry when there are too many pages of notes. I prefer companies that don’t need so many pages to explain what is happening. I like companies that are able to keep their operations simple. Certainly, a great amount of important information can be gleaned from a careful study of the financial statements in any company’s annual report.

One of the great things about our current state of technology is that an investor can find a company’s annual report on the Internet in a matter of seconds. You can download information provided by two or three companies and make instant comparisons. That is so helpful for analysis purposes.

Video Clip

(click to see video)Professor Joe Hoyle talks about the five most important points in Chapter 3 "How Is Financial Information Delivered to Decision Makers Such as Investors and Creditors?".