This is “Government’s Role in Managing the Economy”, section 1.7 from the book An Introduction to Business (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.7 Government’s Role in Managing the Economy

Learning Objective

- Discuss the government’s role in managing the economy.

In every country, the government takes steps to help the economy achieve the goals of growth, full employment, and price stability. In the United States, the government influences economic activity through two approaches: monetary policy and fiscal policy. Through monetary policyEfforts exerted by the Federal Reserve System (“the Fed”) to regulate the nation’s money supply., the government exerts its power to regulate the money supply and level of interest rates. Through fiscal policyGovernmental use of taxation and spending to influence economic conditions., it uses its power to tax and to spend.

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is exercised by the Federal Reserve System (“the Fed”), which is empowered to take various actions that decrease or increase the money supply and raise or lower short-term interest rates, making it harder or easier to borrow money. When the Fed believes that inflation is a problem, it will use contractionary policy to decrease the money supply and raise interest rates. When rates are higher, borrowers have to pay more for the money they borrow, and banks are more selective in making loans. Because money is “tighter”—more expensive to borrow—demand for goods and services will go down, and so will prices. In any case, that’s the theory.

Figure 1.12

The Fed will typically tighten or decrease the money supply during inflationary periods, making it harder to borrow money.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

To counter a recession, the Fed uses expansionary policy to increase the money supply and reduce interest rates. With lower interest rates, it’s cheaper to borrow money, and banks are more willing to lend it. We then say that money is “easy.” Attractive interest rates encourage businesses to borrow money to expand production and encourage consumers to buy more goods and services. In theory, both sets of actions will help the economy escape or come out of a recession.

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy relies on the government’s powers of spending and taxation. Both taxation and government spending can be used to reduce or increase the total supply of money in the economy—the total amount, in other words, that businesses and consumers have to spend. When the country is in a recession, the appropriate policy is to increase spending, reduce taxes, or both. Such expansionary actions will put more money in the hands of businesses and consumers, encouraging businesses to expand and consumers to buy more goods and services. When the economy is experiencing inflation, the opposite policy is adopted: the government will decrease spending or increase taxes, or both. Because such contractionary measures reduce spending by businesses and consumers, prices come down and inflation eases.

The National Debt

If, in any given year, the government takes in more money (through taxes) than it spends on goods and services (for things such as defense, transportation, and social services), the result is a budget surplus. If, on the other hand, the government spends more than it takes in, we have a budget deficit (which the government pays off by borrowing through the issuance of Treasury bonds). Historically, deficits have occurred much more often than surpluses; typically, the government spends more than it takes in. Consequently, the U.S. government now has a total national debtTotal amount of money owed by the federal government. of more than $14 trillion.

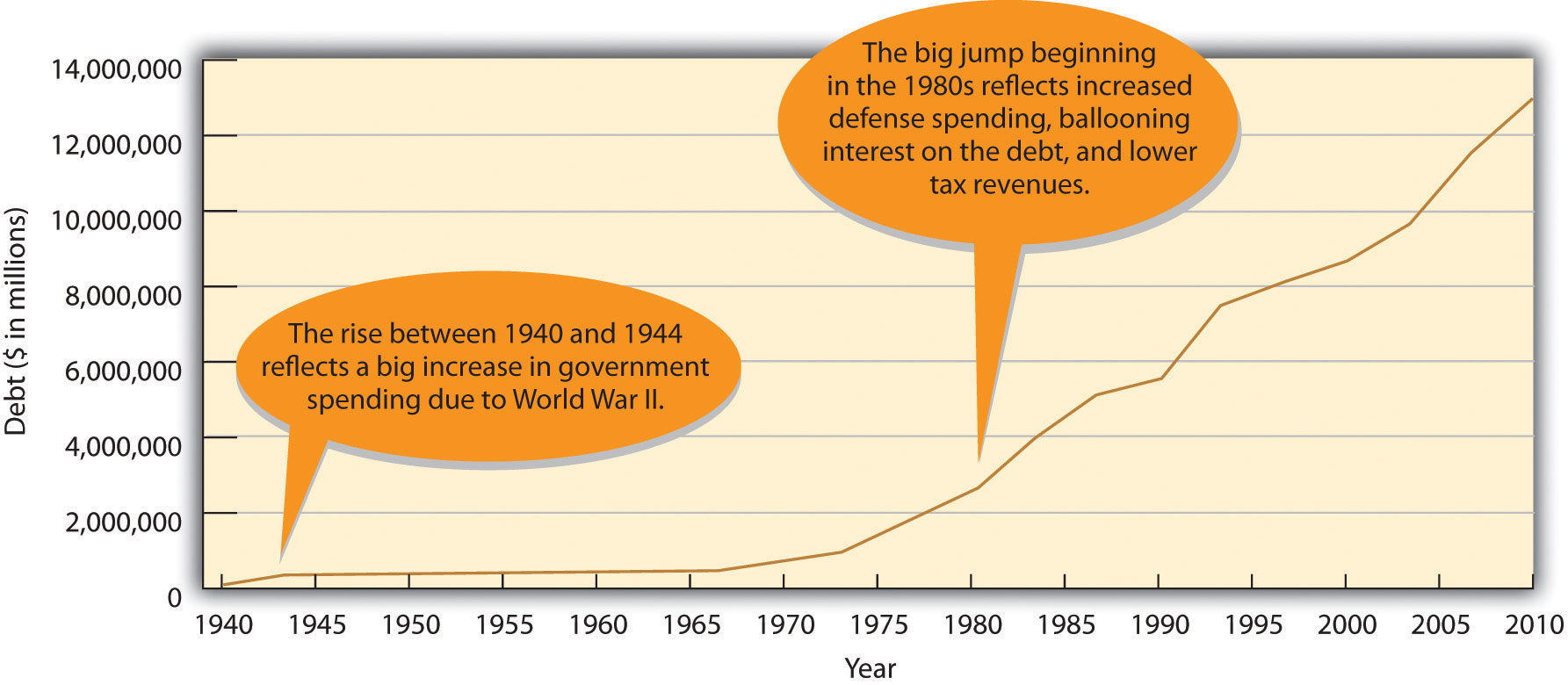

As you can see in Figure 1.13 "The U.S. National Debt, 1940–2010", this number has risen dramatically in the last sixty-five years. The significant jump that starts in the 1980s reflects several factors: a big increase in government spending (especially on defense), a substantial rise in interest payments on the debt, and lower tax rates. As of this writing, your share is $46,146.21. If you want to see what the national debt is today—and what your current share is—go on the Web to the U.S. National Debt Clock (http://www.brillig.com/debt_clock).

Figure 1.13 The U.S. National Debt, 1940–2010

Macroeconomics and Microeconomics

In the preceding discussion, we’ve touched on two main areas in the field of economics: (1) macroeconomics, or the study of the economy as a whole, and (2) microeconomics, or the study of the economic choices made by individual consumers or businesses. Macroeconomics examines the economy-wide effect of inflation, while microeconomics considers such decisions as the price you’re willing to pay to go to college. Macroeconomics investigates overall trends in imports and exports, while microeconomics explains the price that teenagers are willing to pay for concert tickets. Though they are often regarded as separate branches of economics, we can gain a richer understanding of the economy by studying issues from both perspectives. As we’ve seen in this chapter, for instance, you can better understand the overall level of activity in an economy (a macro issue) through an understanding of supply and demand (a micro issue).

Key Takeaways

- The U.S. government uses two types of policies—monetary policy and fiscal policy—to influence economic performance. Both have the same purpose: to help the economy achieve growth, full employment, and price stability.

- Monetary policy is used to control the money supply and interest rates.

- It’s exercised through an independent government agency called the Federal Reserve System (“the Fed”), which has the power to control the money supply and interest rates.

- When the Fed believes that inflation is a problem, it will use contractionary policy to decrease the money supply and raise interest rates. To counter a recession, it will use expansionary policy to increase the money supply and reduce interest rates.

- Fiscal policy uses the government’s power to spend and tax.

- When the country is in a recession, the government will increase spending, reduce taxes, or do both to expand the economy.

- When we’re experiencing inflation, the government will decrease spending or increase taxes, or both.

- When the government takes in more money in a given year (through taxes) than it spends, the result is a surplus.

- When the opposite happens—government spends more money than it takes in—we have a deficit.

- The cumulative sum of deficits is the national debt—the total amount of money owed by the federal government.

Exercises

- Let’s say that you’re the Fed chairperson and that the country is in a recession. What actions should the Fed take to pull the country out of the recession? What would you advise government officials to do to improve the economy? Justify your recommendations.

- Browsing through your college’s catalog, you notice that all business majors must take two economics courses: macroeconomics and microeconomics. Explain what’s covered in each of these courses. In what ways will the things you learn in each course help you in the future?