This is “Becoming a Critical Reader”, chapter 2 from the book Writers' Handbook (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 2 Becoming a Critical Reader

This chapter will help you put into practice the strategies of mindful and reflective questioning introduced in Chapter 1 "Writing to Think and Writing to Learn". After surveying a Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts", you will learn what can be accomplished from using critical thinking methods when reading texts closely and carefully. You will also see how a single text can be opened up through careful and close reading as a model for what can be done with texts from a wide variety of media and genres. You’ll learn to be attentive to not only what a text is trying to say but also how it is saying it. By deepening your understanding of the interactions among self, text, and context, you’ll come to appreciate how crucial your role in the critical reading process is, not only to your comprehension, but also to your genuine enjoyment of any text.

2.1 Browsing the Gallery of Web-Based Texts

Learning Objectives

- Show how the web can be mined for a wealth of academically useful content.

- Introduce the concept of writing essays based on free, web-based texts.

- Explore how such texts lend themselves to critical inquiry.

Given that the focus of this chapter is on reading texts, the first section introduces a Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts". Think of this alphabetical, annotated collection of websites as an alternative collection of readings to which you and your instructor can return at other points in the course. If your instructor is assigning a traditional, bound reader in addition to this handbook, these sites might be purely supplemental, but if not, they might serve as a storehouse from which to build a free do-it-yourself reader that could be central to the work you do in your composition course.

Regardless of how you use these archives of texts, they’re meant to inspire you and your instructor to go on a scavenger hunt for other authoritative collections on the web. If your instructor is using a course management systemA web-based learning environment that organizes the work of a course (e.g., Blackboard). (like Blackboard) or a class-wide wikiAn interactive, shared website featuring content that can be edited by many users., these sites could easily be lodged in a document library of external links, and you and your instructor could add sites as you discover (and annotate) them. (Or, of course, additional sites may be added to this very chapter by your instructor through Flat World Knowledge’s customization feature.)

This collection of web-based archives, even though it references several million texts, merely scratches the surface of the massive amount of material that’s freely available on the web. Remember, too, that your college library has likely invested heavily in searchable academic databases to which you have access as a student. Faculty members and librarians at your institution may already be at work creating in-house collections of readings drawn from these databases. (For more on such databases, see Chapter 7 "Researching", Section 7.2 "Finding Print, Online, and Field Sources" and consult your college’s library staff.)

Because these noncommercial, nonpartisan websites are sponsored by governmental and educational entities and organizations, they are not likely to disappear, but there are no guarantees. If links go dead, try your favorite search engine to see if the documents you’re seeking have been lodged elsewhere.

The selection principle for this gallery is that the sites listed should be free of cost, free of commercial advertisements, free of partisanshipTaking an entirely one-sided point of view about a subject. (though multiple sides are often presented), and free of copyright wherever possible. If you’re not bothered by ads, you’ll find a wealth of additional content, much of which will be very useful.

Finally, remember, just because these sites are free of charge and free of copyright doesn’t mean you don’t have to cite them appropriately if you end up using content from them in your writing. See Chapter 22 "Appendix B: A Guide to Research and Documentation" of this book for information on how to document electronic texts. You and your instructor also need to be aware of any copyright restrictions on duplicating and redistributing content on these sites. These restrictions will usually be found at the site itself, but when in doubt, consult your college library staff.

Gallery of Web-Based Texts

Title: The Ad Council

Brief description: Includes an archive of more than sixty-five years of public service advertising campaigns in print, radio, and television media.

Possible uses: Analyses of rhetorical technique in advertising; studies requiring historical context; comparisons of commercial and public-service marketing.

***

Title: American Experience

URL: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience

Brief description: Full-length documentaries produced by the Public Broadcasting System (PBS), many available for viewing online, with additional resources provided at each film’s website.

Possible uses: Studies requiring historical context, comparisons of documentary and popular filmmaking, and comparisons of education and entertainment.

***

Title: Arts and Letters Daily

Brief description: A clearinghouse of web-based content (from magazines, newspapers, and blogs) on culture and current affairs sponsored by the Chronicle of Higher Education, updated daily, and archived from 1998 to the present.

Possible uses: Essays on contemporary topics; studies of the style and ideological cast of a particular commentator or columnist; generating ideas for possible topics for further research.

***

Title: The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy

URL: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/major.asp

Brief description: Yale University Law School’s collection of documents, including among many other items “Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents” (from which the demonstration text in Section 2.3 "Reading a Text Carefully and Closely" is taken).

Possible uses: Cross-disciplinary writing projects in history, religion, and political science; analyses of rhetorical and argumentative strategies.

***

Title: Big Questions Essay Series

URL: http://www.templeton.org/signature-programs/big-questions-essay-series

Brief description: A growing collection from the nonprofit Templeton Foundation, made up of essays by writers from different disciplines and backgrounds on several “big questions” (about a dozen essays per question).

Possible uses: Essay assignments on “great questions” requiring citation of conflicting sources; exercises on exploring alternative points of view; analyses of how biases, assumptions, and implications affect argument and rhetoric.

***

Title: C-SPAN Video Library

URL: http://www.c-spanvideo.org/videoLibrary

Brief description: An archive of more than 160,000 hours of digitized video programming on C-SPAN since 1987, including thousands of political debates and campaign ads; also applicable for the education category (see library for hundreds of commencement addresses).

Possible uses: Analyses of political advertising and comparisons with other kinds of commercials; analytical summaries of ideological positions along the American political spectrum from 1987 to the present; analyses of argumentative technique in political debates.

***

Title: From Revolution to Reconstruction…and What Happened Afterwards

URL: http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/index.htm

Brief description: A collection of documents from American history from the colonial period to the present, sponsored by the United States Information Agency (USIA).

Possible uses: Analyses of rhetorical and argumentative strategies of documents in American history and government.

***

Title: Gallup

URL: http://www.gallup.com/home.aspx

Brief description: More than seventy-five years of polling data on myriad subjects, with constant updates from contemporary polls.

Possible uses: Analyses of American political and social trends from the 1930s to the present; comparisons with contemporaneous, parallel polls from other organizations; political science studies of polling methodology.

***

Title: Google Books

Brief description: Includes not only in-copyright/in-print and in-copyright/out-of-print books for purchase but also out-of-copyright books as free downloads.

Possible uses: Access to free, out-of-print, out-of-copyright, older, book-length content for historical, sociological studies.

***

Title: The Internet Archive

Brief description: Created by The Internet Archive, a nonprofit organization founded in 1996 that is committed to preserving digitized materials, this collection includes not only websites in their original forms but also audio and video collections.

Possible uses: Historical analyses of websites since their inception; popular cultural analyses of film, television, radio, music, and advertising.

***

Title: The Living Room Candidate

URL: http://www.livingroomcandidate.org

Brief description: A collection of hundreds of television advertisements of presidential campaigns from 1952 to the present, sponsored and operated by the Museum of the Moving Image.

Possible uses: Analyses of the rhetoric of political television advertising across time (from 1952 to the present); comparisons between television and print advertising in politics; summaries of political party positions and ideologies.

***

Title: MIT Open Courseware

URL: http://ocw.mit.edu/index.htm

Brief description: One of the best collections of university lectures on the web, along with Yale’s (see Open Yale Courses).

Possible uses: Completely free access to complete lecture-based courses from some of the best professors on earth in almost every conceivable university subject.

***

Title: The National Archives Experience: Docs Teach

URL: http://docsteach.org

Brief description: Classroom activities, reading and writing assignments accompanied by document collections from the National Archives, each concentrating on a specific historical era.

Possible uses: Ready-made reading and writing assignment sequences of primary documents from American history; cross-disciplinary writing projects in history, religion, political science, and cultural geography.

***

Title: The Online Books Page

URL: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/books

Brief description: A collection of more than forty thousand free books, as well as an extensive e-archive of e-archives (see Archives and Indexes/General), edited by John Mark Ockerbloom at the University of Pennsylvania since 1993.

Possible uses: Access to free, out-of-print, out-of-copyright, older, book-length content for historical, sociological studies; cross-disciplinary writing projects in history, religion, political science, and cultural geography.

***

Title: Open Yale Courses

URL: http://oyc.yale.edu

Brief description: One of the best collections of university lectures on the web, along with MIT’s (see MIT Open Courseware).

Possible uses: Completely free access to complete lecture-based courses from some of the best professors on earth in almost every conceivable subject.

***

Title: Project Gutenberg

URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Main_Page

Brief description: The most established collection of more than thirty-three thousand book-length works originally published in paper form, digitized and downloadable in a variety of formats, and free of American copyright.

Possible uses: Analyses of older, book-length literary texts; studies of specific historical and cultural phenomena.

***

Title: the Poetry Foundation

URL: http://www.poetryfoundation.org

Brief description: Thousands of poems and poetry-related material collected into a searchable archive, managed and operated by the Poetry Foundation.

Possible uses: Analyses of poems and poetic language; studies of specific themes as expressed through the humanities.

***

Title: The Smithsonian Institution Research Information System (SIRIS): Collections Search Center

URL: http://collections.si.edu/search

Brief description: A vast collection of more than 4.6 million books, manuscripts, periodicals, and other materials from the various museums, archives, and libraries of the Smithsonian Institution.

Possible uses: Historical and rhetorical analyses of texts and resources in a variety of disciplines in the arts and sciences.

***

Title: This I Believe

Brief description: A regular feature of National Public Radio (NPR) since 2006, a series of personal essays read aloud on a variety of topics, archived together with 1950s-era essays from a program of the same name hosted by Edward R. Murrow.

Possible uses: Comparisons of social issues across two historical periods (e.g., 2006 to the present vs. the 1950s); comparisons between the personal essay and other genres of exposition and exploration; comparisons between oral and written texts.

***

Title: The US Census Bureau

Brief description: A trove of demographic statistics and surveys with a variety of themes from the most recent census and those conducted previously.

Possible uses: Summaries, reports, and causal analyses of demographic trends in American society; evaluations of the uses of statistics as evidence; social science studies of polling methodology.

Key Takeaways

- The web affords writing students and instructors countless opportunities to engage with texts in a variety of media and genres.

- The vast majority of web-based texts are available free of charge. A significant minority of publicly and privately funded sites are also free of advertisement and often free of copyright.

- Your status as a college student also puts you in a great position to make use of any online library databases to which your college subscribes.

- Even though web texts are easily accessible, they still need to be documented appropriately when used as part of a writing project.

Exercises

- Individually or in a group, go on a scavenger hunt for another web-based archive of texts that could be useful to your composition class as part of a no-cost alternative to a pricey print collection of readings. Try to meet the same criteria this handbook uses: the collection of texts should be free of charge, free of copyright restriction, free of partisanship, and free of advertising (except for sponsorship information in the case of nonprofit organizations). Write up an annotated entry on what you find, following the same format used in the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts".

- Individually or in a group, get to know the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts" in more detail. Find and critically analyze five to ten individual texts from one archive. Your critical analysis should include answers to at least five of the questions in the list of questions about speaker, audience, statement, and relevance in the next section or at least five of the Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context in Chapter 1 "Writing to Think and Writing to Learn". Be prepared to present your findings in a class discussion, on the class discussion board, or on a class-wide wiki.

- Find two texts from two different archives in the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts" that explore a similar theme or topic in different ways, either from two different ideological perspectives or through two different genres or media. Write an essay that compares and contrasts the two different texts.

2.2 Understanding How Critical Thinking Works

Learning Objectives

- Learn how and why critical thinking works.

- Understand the creative and constructive elements of critical thinking.

- Add to the list of productive questions that can be asked about texts.

“Critical thinking” has been a common phrase in education for more than a quarter century, but it can be a slippery concept to define. Perhaps because “critical” is an adjective with certain negative connotations (e.g., “You don’t have to be so critical” or “Everybody’s a critic”), people sometimes think that critical thinking is a fault-finding exercise or that there is nothing creative about it. But defined fairly and fully, critical thinkingThe ability to separate fact from opinion, to ask questions, to reflect on one’s own role in the process of inquiry and discovery, and to pay close attention to detail. is in fact a precondition to creativity.

Critical thinkers consider multiple sides of an issue before choosing sides. They tend to ask questions instead of accepting everything they hear or read, and they know that answers often only open up more lines of inquiry. Critical thinkers read between the lines instead of reading only at face value, and they also develop a keen sense of how their own minds operate. Critical thinkers recognize that much of the information they read and hear is a combination of fact and opinion. To be successful in college, you will have to learn to differentiate between fact and opinion through logic, questioning, and verification.

Facts are pieces of information that you can verify as true. Opinions are personal views or beliefs that may have very little grounding in fact. Since opinions are often put forth as if they were facts, they can be challenging to recognize as opinions. That’s where critical thinkers tend to keep questioning. It is not enough to question only the obviously opinionated material in a text. Critical thinkers develop a habit of subjecting all textual statements to a whole constellation of questions about the speaker (or writer), the intended audienceThe individual or group being addressed or targeted by a piece of communication., the statement itself, and the relevance of it.

Considering the speaker:

- Who is making this the statement?

- What are the speaker’s affiliations?

- How does the speaker know the truth of this statement?

Considering the audience:

- Who is being addressed with this statement?

- What could connect the speaker of the statement with the intended audience?

- Would all people consider this statement to be true?

Considering the statement:

- Can this statement be proven?

- Will this statement also be true tomorrow or next year?

- If this statement is true, what else might be true?

- Are there other possible interpretations of the facts behind this statement?

Considering relevance:

- What difference does this statement make?

- Who cares (and who should care)?

- So what? What now? What’s next?

Writers naturally write with some basic assumptions. Without a starting point, a writer would have no way to begin writing. As a reader, you have to be able to identify the assumptions a writer makes and then judge whether or not those assumptions need to be challenged or questioned. As an active readerA person who uncovers the biases, preconceptions, assumptions and implications of a text., you must acknowledge that both writers and readers make assumptions as they negotiate the meaning of any text. A good process for uncovering assumptions is to try to think backward from the text. Get into the habit of asking yourself, “In order to make this given statement, what else must this writer also believe?”

Whether you recognize it or not, you also have biases and preconceptions on which you base many decisions. These biases and preconceptions form a screen or a lens through which you see your world. Biases and preconceptions are developed out of your life’s experiences and influences. As a critical thinker who considers all sides of an issue, you have to identify your personal positions and subject them to scrutiny.

Just as you must uncover assumptions—those of the writer as well as your own as a reader—to truly capture what you are reading, you must also examine the assumptions that form the foundation of your writing. And you must be prepared to do so throughout the writing process; such self-questioning can, in fact, be a powerful strategy for revision (as you’ll see in more detail in Chapter 8 "Revising", Section 8.1 "Reviewing for Purpose").

Key Takeaways

- Far from being a negative or destructive activity, critical thinking is actually the foundation of creative, constructive thinking.

- Critical thinkers consider multiple sides of issues, before arriving at a judgment. They must carefully consider the source, the audience, and the relevance of any statement, making a special effort to distinguish fact from opinion in the statement itself.

- Biases and preconceptions are ideas based on life experiences and are common components of most everything you say, hear, or read.

Exercises

-

Use the set of questions at the end of this section about the speaker, audience, statement, and relevance for a text of your choice from the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts" in Section 2.1 "Browsing the Gallery of Web-Based Texts". Here are some promising avenues to pursue:

- A public service announcement (PSA) campaign (Ad Council)

- A “This I Believe” radio essay (This I Believe)

- A television ad spot from a political campaign (The Living Room Candidate)

- An entry in one of the debates on a “big question” (Big Questions Essay Series)

- Use those same questions for a reading from one of your other classes (even a chapter from a textbook) or a reading in your composition class assigned by your instructor.

- Go to the Smithsonian Institution (SIRIS) site in the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts" and click on the Search Collections tab. Use the search phrase “personal hygiene advertisements” and then choose two of the ads that appear in the archive after you’ve browsed the dozens of hits. Apply this section’s questions to two ads you’ve chosen. Then get to know the search engine on the SIRIS site a little better by trying out a few search phrases of your own on topics of interest to you.

2.3 Reading a Text Carefully and Closely

Learning Objectives

- Demonstrate how to do a close reading on a selection from the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts".

- Uncover the assumptions and implications of textual statements and understand how biases and preconceptions affect readers and writers.

- Show how a close reading of any statement is based on uncovering its assumptions, biases, preconceptions, and implications.

In this section, we’ll use an excerpt from one of the most famous inaugural addresses in American history, from John F. Kennedy in 1961, to demonstrate how to do a close reading by separating fact and opinion; uncovering assumptionsA belief that underlies a writer’s proposition or statement., biasesA deeply held and ingrained belief that can cloud one’s perspective as a writer or reader., and preconceptionsAn idea already held by a writer or reader in advance of making or receiving a textual statement.; and pursuing the implicationsWhat readers can infer from statements a writer makes. of textual statements. (The address is available in its entirety through the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts" in Section 2.1 "Browsing the Gallery of Web-Based Texts", in text form at the Avalon Project, and in video form at the C-SPAN Video Library.)

To prepare yourself to develop a thoughtful, critical reading of a text like this, you might begin with the Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context from Chapter 1 "Writing to Think and Writing to Learn", filling in each blank with “Kennedy’s Inaugural Address.”

Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context

Self-Text Questions

- What do I think about Kennedy’s Inaugural Address?

- What do I feel about Kennedy’s Inaugural Address?

- What do I understand or what puzzles me in or about Kennedy’s Inaugural Address?

- What turns me off or amuses me in or about Kennedy’s Inaugural Address?

- What is predictable or surprises me in or about Kennedy’s Inaugural Address?

Text-Context Questions

- How is Kennedy’s Inaugural Address a product of its culture and historical moment?

- What might be important to know about the creator of Kennedy’s Inaugural Address?

- How is Kennedy’s Inaugural Address affected by the genre and medium to which it belongs?

- What other texts in its genre and medium does Kennedy’s Inaugural Address resemble?

- How does Kennedy’s Inaugural Address distinguish itself from other texts in its genre and medium?

Self-Context Questions

- How have I developed my aesthetic sensibility (my tastes, my likes, and my dislikes)?

- How do I typically respond to absolutes or ambiguities in life or in art? Do I respond favorably to gray areas or do I like things more clear-cut?

- With what groups (ethnic, racial, religious, social, gendered, economic, nationalist, regional, etc.) do I identify?

- How have my social, political, and ethical opinions been formed?

- How do my attitudes toward the “great questions” (choice vs. necessity, nature vs. nurture, tradition vs. change, etc.) affect the way I look at the world?

Self-Text-Context Questions

- How does my personal, cultural, and social background affect my understanding of Kennedy’s Inaugural Address?

- What else might I need to learn about the culture, the historical moment, or the creator that produced Kennedy’s Inaugural Address in order to more fully understand it?

- What else about the genre or medium of Kennedy’s Inaugural Address might I need to learn in order to understand it better?

- How might Kennedy’s Inaugural Address look or sound different if it were produced in a different time or place?

- How might Kennedy’s Inaugural Address look or sound different if I were viewing it from a different perspective or identification?

Note that most of these questions can’t be answered until you’ve made a first pass through the text, while others almost certainly require some research to be answered fully. It’s almost a given that multiple readings will be required to fully understand a text, its context, and your orientation toward it.

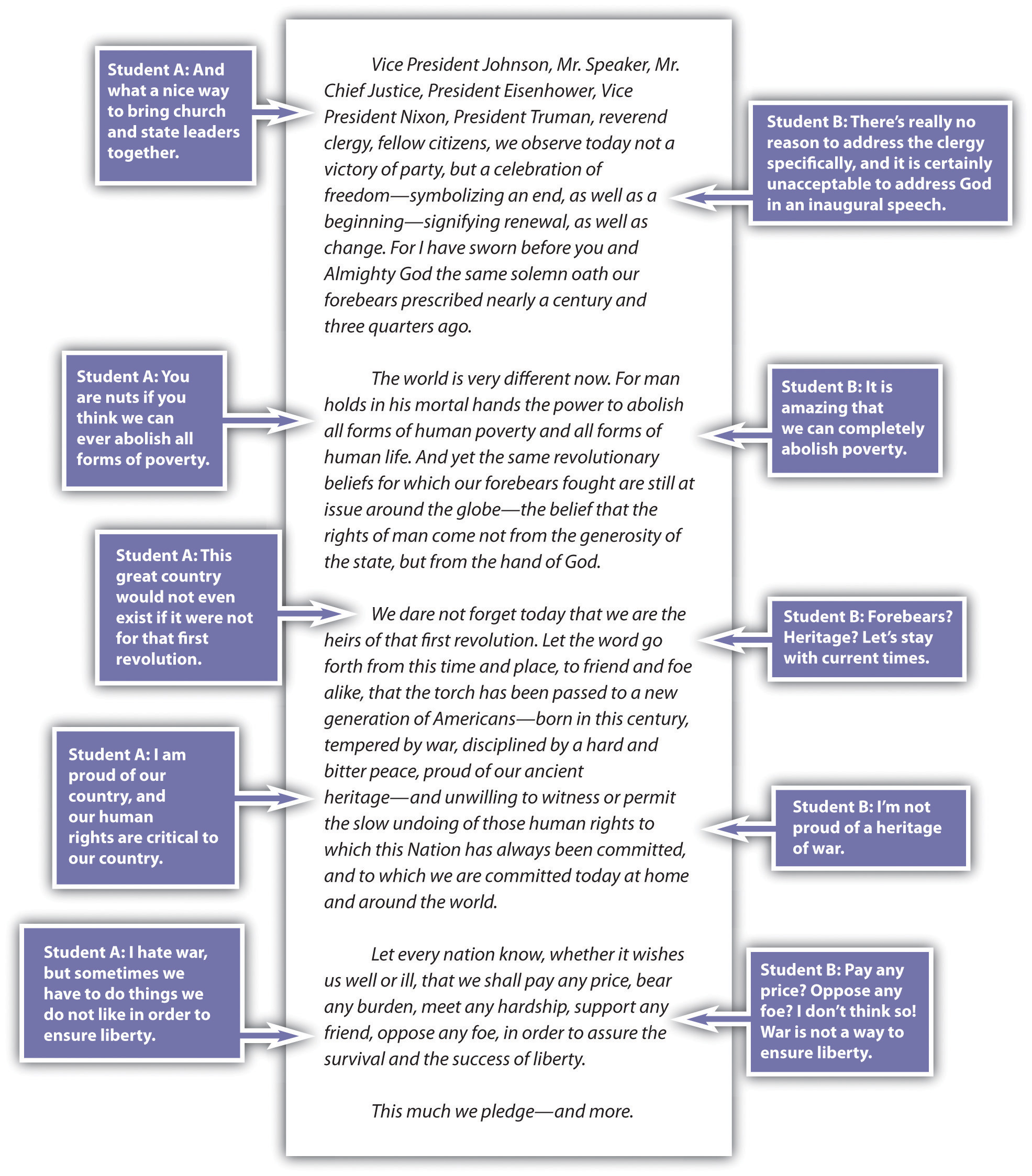

In the first annotation, let’s consider Roger (Student A) and Rhonda (Student B), both of whom read the speech without any advance preparation and without examining their biases and preconceptions. Take a look at the comment boxes attached to the excerpt of the first five paragraphs of Kennedy’s Inaugural Address.

Roger does not have any problem with a lack of separation between church and state. Rhonda is unwilling to accept any reference to God in any government setting. Should Roger at least recognize the rationale for separating church and state? Should Rhonda recognize that while the founders of this country called for such a separation, they also made repeated reference to God in their writings?

Perhaps both Roger and Rhonda should consider that Kennedy’s lofty goal of eliminating poverty was perhaps an intentional rhetorical overreach, typical of inaugural addresses, meant to inspire the general process of poverty elimination and not to lay out specific policy.

Roger sees war as a necessary evil in the search for peace. Rhonda sees war as an unacceptable evil that should never be used as a means to an end. To hear what Kennedy is saying, Roger probably needs to consider options other than war and Rhonda probably needs to recognize that history has shown some positive results from “necessary” wars.

If Roger and Rhonda want to be critical thinkers or even if they want have a meaningful conversation about the text, they must think through and past their own personal biases and preconceptions. They must prepare themselves to be critical readers.

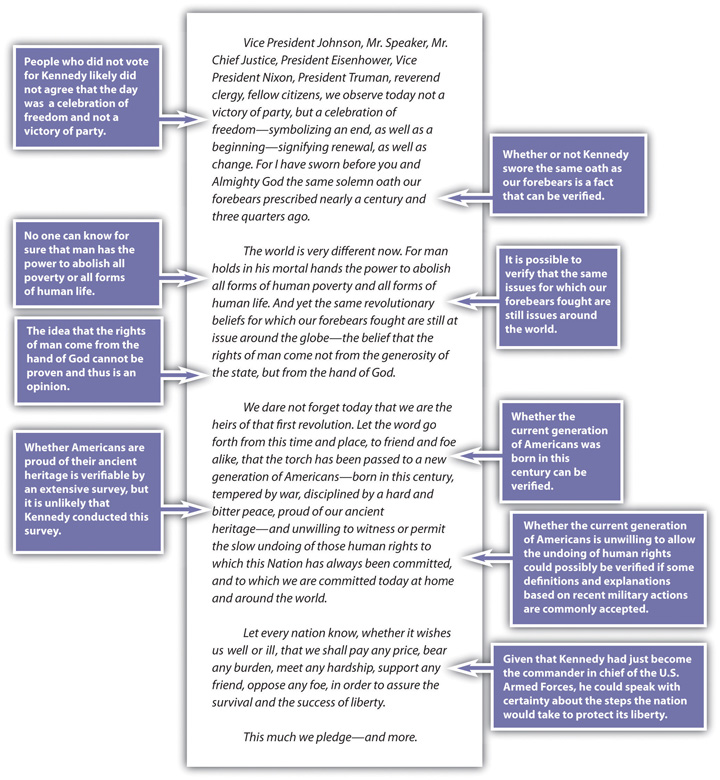

In the next set of annotations, let’s look at what you could do with the text by making several close readings of it, while also subjecting it to the preceding Twenty Questions. Perhaps your first annotation could simply be designed to separate statements of verifiable fact from those of subjective opinion.

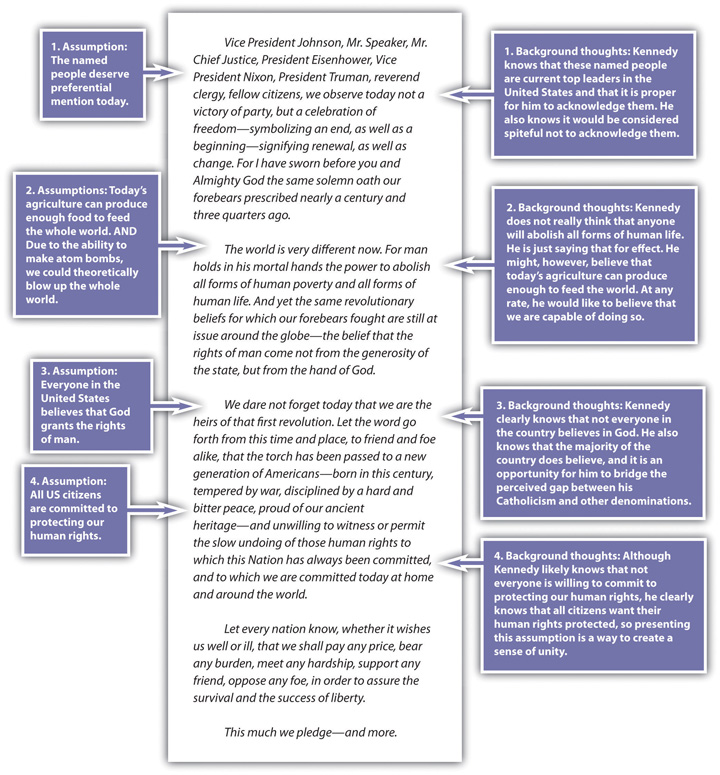

A careful reader who looks for assumptions and implications of statements will find plenty of them. For example, the beginning of Kennedy’s Inaugural Address includes many assumptions. In your second annotation, you might go on to target some of these assumptions and offer background thoughts that help you identify and understand these assumptions.

Just as you must try to trace a statement back to its underlying assumptions, you must also try to understand what a statement implies. Even when different readers are looking at the same text, they can sometimes disagree about the implications of a statement. Their disagreements often form the basis for their divergent opinions as readers.

Take Kennedy’s assumption that the named people at the beginning of his speech deserve preferential attention. Here are some possible implications of the statement you could come up with that result from that single assumption:

- People who voted for Nixon are reminded that their candidate did not get elected, which makes these people angry all over again.

- People who voted for Nixon feel somewhat comforted knowing that Nixon and Eisenhower are being recognized at the inauguration, and they are pleased that Kennedy is acknowledging them.

- Supporters of Kennedy hear his recognition of Nixon and Eisenhower as an acceptance of them, and thus they look more favorably on members of the opposing party.

- Supporters of Johnson appreciate that Kennedy mentions him first and believe that he is giving the most respect of all to Johnson.

- Those concerned about the relative youth of this new president appreciate the deference he shows to tradition by making this rhetorical gesture of salutation.

- Those suspicious of the power of the executive branch might wonder why Kennedy addresses the former presidents and vice president by name but gives only the title of the Supreme Court chief justice and the Speaker of the House.

You could add more to this list of possible implications, but notice how much you’ve done with the first paragraph of the speech already, simply by slowing down your critical reading process.

Key Takeaways

- Virtually any statement carries a set of assumptions (what the writer or speaker assumes in order to make the statement) and implications (what the statement implies to readers or listeners).

- You need to be able to recognize biases and preconceptions in others and in yourself so you can form your ideas and present them responsibly.

Exercises

- Apply some of the critical thinking methods outlined in this section to another presidential inaugural address. For a complete collection, check out the Avalon Project in the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts" at the beginning of the chapter. Click on “Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents” in the main directory. Videos of all inaugural addresses since Truman’s in 1948 can be found at the C-Span Video Library.

- Presidential inaugural addresses, having developed over more than two centuries, follow a certain set of unspoken rules of a highly traditional genre. After looking at three to five other examples of the genre besides Kennedy’s, list at least five things most inaugural addresses are expected to accomplish. Give examples and excerpts of those generic conventions from the three to five other texts you choose. Or try this exercise with other regularly scheduled, ceremonial addresses like the State of the Union.

- Watch at least one hour apiece of prime-time cable news on the Fox News Channel and MSNBC (preferably the same hour or at least the same night of coverage). Catalogue the biases, preconceptions, assumptions, and implications of the news coverage and commentary on the same topic during those two hours. If guest “experts” are interviewed, discuss their political ideologies as well.