This is “Slowing Down Your Thinking”, section 1.3 from the book Writers' Handbook (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.3 Slowing Down Your Thinking

Learning Objectives

- Learn the benefits of thinking more slowly.

- Learn the benefits of thinking of the world in smaller chunks.

- Apply slower, more “small-bore” thinking to a piece of student writing.

Given the fast pace of today’s multitasking world, you might wonder why anyone would want to slow down their thinking. Who has that kind of time? The truth is that college will probably present you with more of an opportunity to slow down your thinking than any other time of your adult life. Slowing down your thinking doesn’t mean taking it easy or doing less thinking in the same amount of time. On the contrary, learning to think more slowly is a precondition to making a successful, meaningful contribution to any discipline. The key is to adjust your perspective toward the world around you by seeing it in much smaller chunks.

When you get a writing assignment in a broad topic area asking for a certain number of words or pages (let’s say 1,000 to 1,250 words, or 4 to 5 double-spaced pages, with 12-point font and 1-inch margins), what’s your first reaction? If you’re like most students, you might panic at first, wondering how you’re going to produce that much writing. The irony is that if you try to approach the topic from a perspective that is too general, what you write will likely be as painful to read as it is to write, especially if it’s part of a stack of similarly bland essays. It will inevitably be shallow because a thousand words on ten ideas works out to about a hundred words per idea. But if you slow down your thinking to find a single aspect of the larger topic and devote your thousand words to that single aspect, you’ll be able to approach it from ten different angles, and your essay will distinguish itself from the pack.

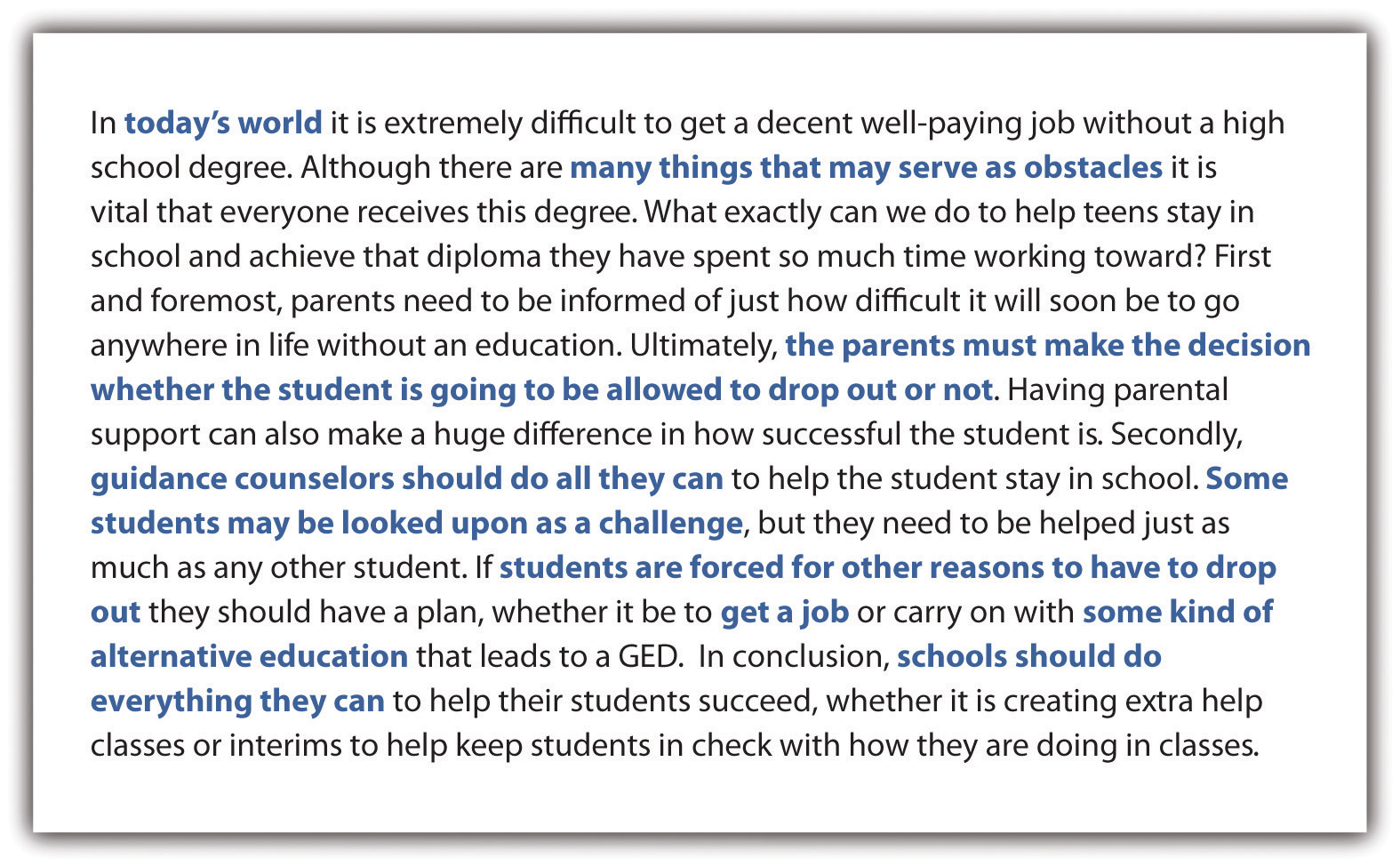

Let’s try this with an excerpt of student writing on high school dropouts that was conducted at warp speed. Either the writer was eager to complete the assignment or she hurried to a conclusion without examining the elements of her topic that she was taking for granted. Every sentence or phrase that could benefit from slower thinking in smaller chunks is set in bold blue font.

This example is not given to find fault with the student’s approach, however rushed it might have been. Each of the bold blue passages is not technically a mistake, but rather a missed opportunity to take a deeper, more methodical approach to a complicated problem. From this one paragraph, one could imagine as many as eight completely researched, full-length essays emerging on the following topics.

| Missed Opportunity | Possible Essay Topic |

|---|---|

| “Today’s world” | A historical comparison with other job markets for high school dropouts |

| “Many things that may serve as an obstacle” or “students are forced for other reasons to have to drop out” | A study of the leading causes of the high school dropout rate |

| “The parents must make the decision whether the student is going to be allowed to drop out or not” | A study of the dynamics of parent-teen relationships in households where the teen is at risk academically |

| “Guidance counselors should do all they can” | An analysis of current practices of allocating guidance counseling to a wide range of high school students |

| “Some students may be looked upon as a challenge” | A profile of the most prominent characteristics of high school students who are at risk academically |

| “Get a job” | A survey of employment opportunities for high school dropouts |

| “Some kind of alternative education” | An evaluation of the current GED (General Educational Development) system |

| “Schools should do everything they can” | A survey of best practices at high schools across the country that have substantially reduced the dropout rate |

The questions you’ve encountered so far in this chapter have been designed to encourage mindfulness, the habit of taking nothing for granted about the text under examination. Even (or especially) when “the text under examination” happens to be your own, you can apply that same habit. The question “What is it I am taking for granted about ____________?” has several variants:

- What am I not asking about _____________ that I should be asking?

- What is it in _____________ that is not being said?

- Is there something in ____________ that “goes without saying” that nonetheless should be said?

- Do I feel like asking a question when I look at ___________ even though it’s telling me not to?

Slowing down your thinking isn’t an invitation to sit on the sidelines. If anything, you should be in a better position to make a real contribution once you’ve learned to focus your communication skills on a precise area of most importance to you.

Key Takeaways

- Even in a world of high-speed multitasking, thinking deliberately about small, specific things can pay great academic and professional dividends.

- Disciplines and professions rely on many participants thinking and writing about many small-bore topics over an extended period of time.

- Practically any text, especially an early piece of your writing or that of a classmate, can benefit from at least one variation on the question, “What is it I am taking for granted?”

Exercises

- Take a piece of your writing from a previous class or another class you are currently taking, or even from this class, and subject it to a thorough scouring for phrases and sentences that exhibit rushed thinking. Set up a chart similar to the one that appears in this section, listing every missed opportunity and every possible essay topic that emerges from the text once your thinking is slowed down.

- Now try this same exercise on a classmate’s piece of writing, and offer up one of your own for them to work on.

-

Sometimes texts demonstrate thinking that is sped up or oversimplified on purpose, as a method of misleading readers. Find an example of a text that’s inviting readers or listeners to take something for granted or to think too quickly. (You might look in the Note 2.5 "Gallery of Web-Based Texts" in Chapter 2 "Becoming a Critical Reader" to find examples.) Subject the example you find to the questions in this section. Bring the example and your analysis of it to class for discussion or include both the example and your analysis in your group’s or class’s discussion board. Choose from among one of the following categories or come up with a category of your own:

- An editorial column

- A bumper sticker

- A billboard

- A banner on a website

- A political slogan or speech

- A financial, educational, or occupational document

- A song lyric

- A movie or television show plotline

- A commercial advertisement

- A message from a friend or family member