This is “Income Taxes”, chapter 27 from the book Theory and Applications of Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 27 Income Taxes

Tax Day

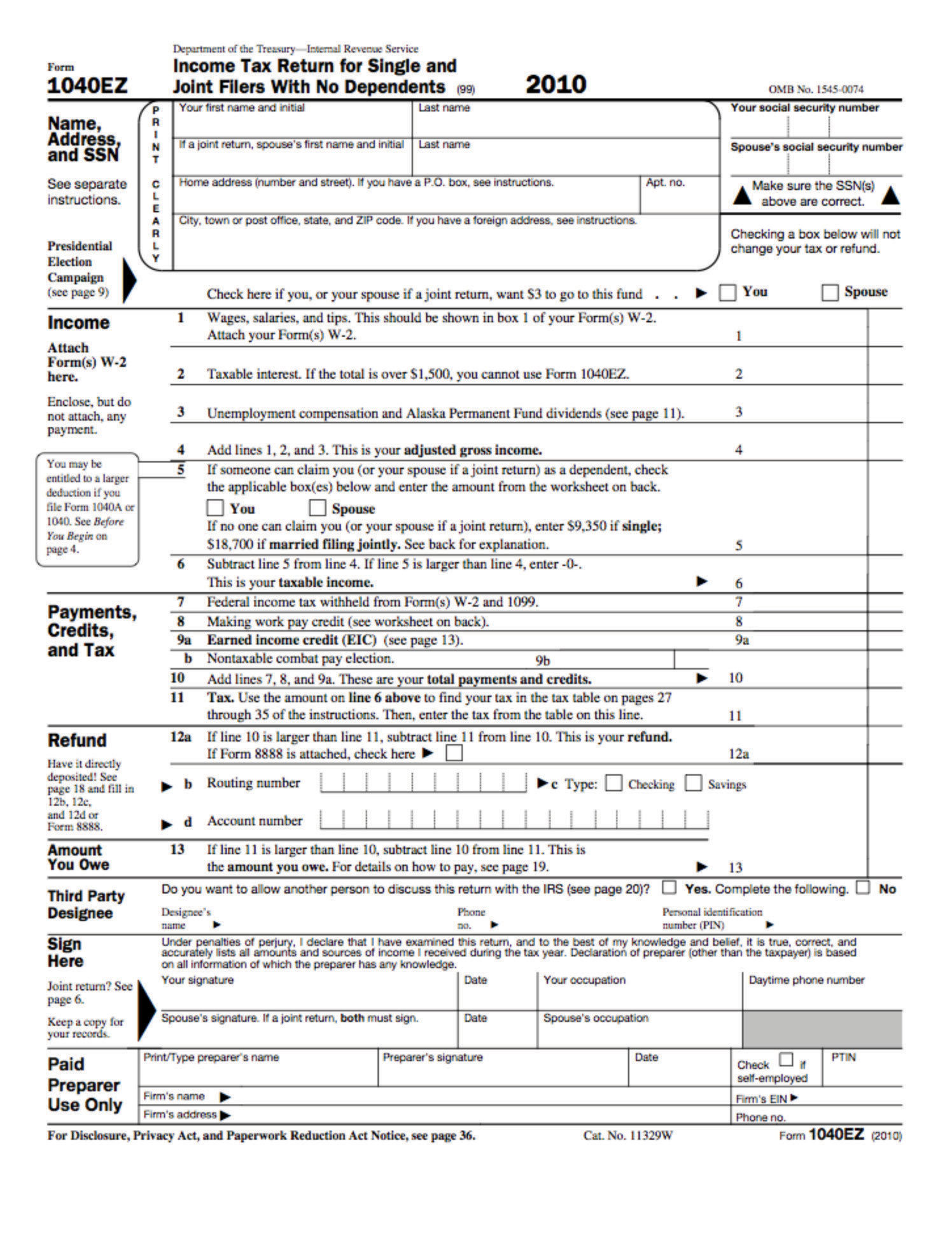

Every year, in the middle of April, US citizens and residents are required to file an income tax form. The following figure shows the 1040EZ tax form, which is the simplest of all these tax forms. For the majority of us, this is one of the most direct pieces of contact that we have with the government. Based on the declarations we file, we are required to pay taxes on the income we have earned over the year. These tax revenues are used to finance a wide variety of government purchases of goods and services and transfers to households and firms. Of course, income taxes are not unique to the United States; most other countries require their residents to complete a similar kind of form.

Figure 27.1 Easy Tax Form

From the perspective of a household or a firm, the tax form is a statement of financial responsibility. From the viewpoint of the government, the 1040 tax form is an instrument of fiscal policy. The 1040 form is based on the US tax code, and changes in that code can have profound effects on the economy—both in the short run and in the long run.

In this chapter, we study the various ways in which income taxes affect the economy. An understanding of taxes is critical for policymakers who devise tax policies and for voters who elect them. Tax policies are often controversial, in large part because they affect the economy in several different ways. For example, in the 2004 and 2008 US presidential campaigns, one of the most contentious economic policy issues was an income tax cut that President George W. Bush had initiated in his first term and that the Republican Party wished to make permanent. That issue returned to the forefront of political discussion in 2010, when these tax cuts were renewed.

Politicians have argued about such matters since the country was founded. Should the government ensure it has enough tax revenue to balance its budget? How should we raise the revenues to pay for our government programs? What is the appropriate tax on the income received by individuals and corporations? Fiscal policy questions like these are debated in the United States and other countries throughout the world. They are tough questions for politicians and economists alike.

Politicians focus largely on who wins and loses—which groups will bear the burden of taxes and receive the benefits of government spending and transfers? They do so for political reasons and because one goal of a tax system is to redistribute income. Economists emphasize something rather different. Economists know that taxes are necessary to finance government expenditures. At the same time, they know that taxes can have the negative effect of distorting people’s decisions and lead to inefficiency. Hence economists focus on designing a tax system that achieves its goals of raising revenue and redistributing income, without distorting the decisions of individuals and firms too much.

In addition, macroeconomists have observed that taxes significantly affect overall economic performance, as measured by variables such as real gross domestic product (real GDP) growth or the unemployment rate. The government can use changes in taxes as a means of influencing aggregate spending in the economy. In the United States, the federal government has often changed income taxes to affect overall economic performance. In this chapter, we examine two examples: the tax policies of the Kennedy administration of 1960–63 and the Reagan administration of 1980–88.

Our discussion of the Kennedy tax cut experience highlights the way in which variations in income taxes are used to help stabilize the macroeconomy. We use the Reagan tax cuts of the early 1980s to explore the growth implications of income taxes, which are often called “supply-side effects.”

Road Map

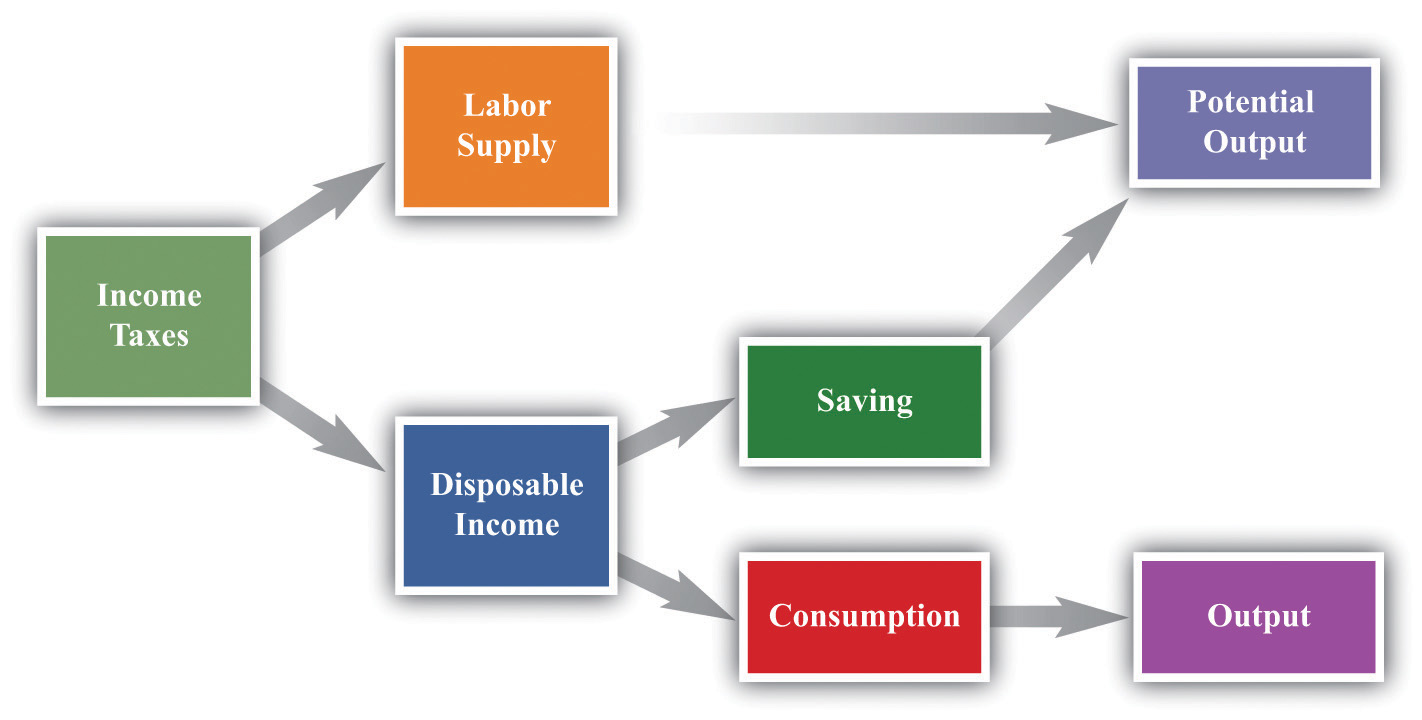

Our approach to understanding the effects of income taxes on the economy is summarized in Figure 27.2 "Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Policy":

- Taxes affect consumption and hence aggregate expenditure and output.

- Taxes affect saving and hence the capital stock and output.

- Taxes affect labor supply and hence output.

Figure 27.2 Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Policy

Any change in the income tax regime affects both the spending and the supply sides of the economy. Our reason for thinking separately about the Kennedy and Reagan tax experiments is to isolate the spending effects and the supply effects. Once you understand these different channels, you will be equipped to evaluate other tax policies, such as those adopted later by President George W. Bush. Finally, the figure reveals that the choice between consumption and saving and the choice between work and leisure are at the heart of our analysis.