This is “Limits on Trade across Borders”, section 12.2 from the book Theory and Applications of Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

12.2 Limits on Trade across Borders

Learning Objectives

- What is the source of gains to trade across two countries?

- Why do governments put restrictions on trade across borders?

- How do governments restrict international trade?

Restrictions do not appear only within a country. We see restrictions on trade across countries as well. In our shopping list at the beginning of the chapter, we mentioned several goods that are imported from other countries, such as Cuban cigars and French cheese. We begin by reviewing the motivations for trade between countries. Just as individuals are motivated to trade by the fact that it can make them better off, countries can also benefit from trading with each other.

Comparative Advantage

The principle of comparative advantage provides one reason why there are gains from trade among individuals.We discuss this in Chapter 6 "eBay and craigslist". Because different individuals have different skills and abilities, everyone can benefit if people specialize in the things that they do relatively well and trade with others to obtain the goods and services that they do not produce. Such specialization is a cornerstone of our modern economy, in which people are specialists in production but generalists in consumption.

The idea of comparative advantage also provides a basis for trade among countries. In the absence of trade, countries end up producing goods and services that they can provide only very inefficiently. When countries trade, they can instead specialize in the goods and the services that they can produce relatively efficiently. All countries can take full advantage of their different capabilities.

We illustrate comparative advantage in a simple way, with a story about trade between Guatemala and Mexico. If you understand this story, you should also be able to see that we could make the example more complex and yet still keep the same basic insight. Table 12.1 "Beer and Tomato Production in Mexico and Guatemala" provides information about the technologyA means of producing output from inputs. in each country: how much a typical individual can produce in a 36-hour workweek. The table shows how much time is required in each country to produce two goods: beer and tomatoes.

Table 12.1 Beer and Tomato Production in Mexico and Guatemala

| Hours of Labor Required | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tomatoes (1 kilogram) | Beer (1 liter) | |

| Guatemala | 6 | 3 |

| Mexico | 2 | 2 |

In both Mexico and Guatemala, people like to consume beer and tomatoes in equal quantities: 1 liter of beer to accompany each kilogram of tomatoes. In Guatemala, it takes 6 hours of labor to produce 1 kilogram of tomatoes, and 3 hours of labor to produce 1 liter of beer. In 9 hours, therefore, it is possible to produce 1 kilogram of tomatoes and 1 liter of beer. In a 36-hour week, the worker can enjoy 4 kilograms of tomatoes accompanied by 4 liters of beer.

Mexico is much more efficient at producing both tomatoes and beer. It takes only 2 hours to produce 1 kilogram of tomatoes, and it takes only 2 hours to produce 1 liter of beer. In 36 hours, therefore, a Mexican worker can produce 9 kilograms of tomatoes and 9 liters of beer.

Because Mexico is better at producing both tomatoes and beer—it has an absolute advantage in the production of both goods—it would be natural to think that Mexico has nothing to gain from trading with Guatemala. But this conclusion is wrong. Mexico is a bit better at producing beer but a lot better at producing tomatoes. Guatemala has a comparative advantage in the production of beer. One way to see this is through opportunity cost. In Guatemala, the opportunity cost of producing 1 kilogram of tomatoes is 2 liters of beer. In Mexico, the opportunity cost of producing 1 kilogram of tomatoes is only 1 liter of beer. Thus Guatemala should specialize in the production of beer.

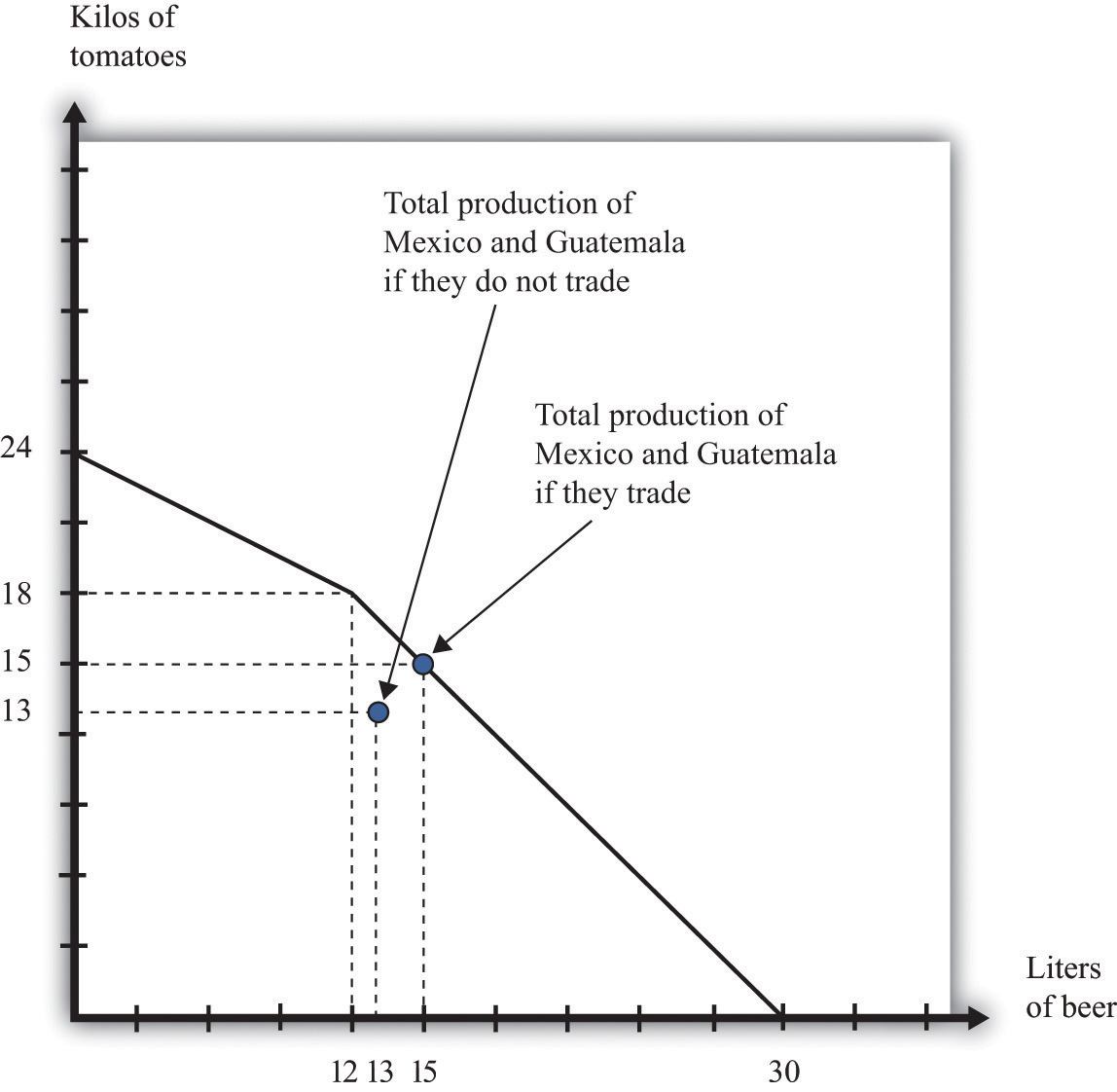

In a 36-hour week, Guatemala produces 12 liters of beer. Now suppose Mexico devotes 30 hours to producing tomatoes and only 6 hours to producing beer. Then Mexico will produce 15 kilograms of tomatoes and 3 liters of beer. The two countries produce, in total, 15 kilograms of tomatoes and 15 liters of beer. Previously, they were producing 13 kilograms of tomatoes and 13 liters of beer. Both countries can be better off if they trade and take advantage of comparative advantage. We illustrate this in Figure 12.13 "The Production Possibilities Frontier".If you have read Chapter 6 "eBay and craigslist", then this figure should look familiar. A similar figure shows up there for trade between two individuals. It shows the joint production possibilities frontier for Guatemala and Mexico. When they produce individually and do not trade, they end up at a point inside the production possibilities frontier. If they specialize and trade, they end up on the production possibilities frontier instead.

Toolkit: Section 31.12 "Production Possibilities Frontier", and Section 31.13 "Comparative Advantage"

You can review the idea of the production possibilities frontier and the concepts of comparative and absolute advantage in the toolkit.

Figure 12.13 The Production Possibilities Frontier

Individually, Mexico and Guatemala produce 13 kilograms of tomatoes and 13 liters of beer. Jointly, they can produce 15 kilograms of tomatoes and 15 liters of beer by exploiting comparative advantage.

Why Do Governments Intervene in International Trade?

To economists, the logic of comparative advantage is highly compelling. Yet noneconomists are much less convinced about the desirability of free trade between countries. We see this reflected in the fact that countries erect a multitude of barriers to trade. Where economists see the possibility of free trade and mutual gain, others often see unfair competition. For example, many countries in the developing world have very low wages compared to the United States, Europe, and other relatively developed economies. Economists see this as a source of comparative advantage for those countries. Because labor is cheap, those countries can produce goods that require a large amount of labor. Countries like the United States, by contrast, can specialize in the production of goods that require less labor. The logic of comparative advantage suggests that both countries would be made better off. To noneconomists, however, the cheap labor looks like “unfair” competition—how can workers in rich countries compete with workers in poor countries who are paid so much less?

This concern has some merit. Comparative advantage tells us that a country as a whole is made better off by trade because that country can have more goods available for consumption. Yet comparative advantage, in and of itself, says nothing about who gets those benefits or how they are shared.

Hypothetically, it is possible to share these goods so that everyone is made better off.Actually, even this statement carries an implicit assumption that it is possible to share out these goods without distorting economic activity too much. In Chapter 13 "Superstars", we explain that redistribution typically involves some loss in efficiency. As a practical matter, even if the country as a whole has more goods and services to consume, some individuals within the country are made worse off. There are winners and losers from trade, and there is frequently political pressure to limit international trade from or on behalf of those who lose out.

Another reason governments intervene in international trade is because of political lobbying. Generally, the beneficiaries from trade barriers are a small and identifiable group. For example, the United States provides sugar subsidies that increase the price of sugar. Sugar producers are the clear beneficiaries of this policy and have an incentive to lobby the government to ensure that the subsidies stay in place. The losers from this policy are those who consume sugar—that is, all of us. But there is no lobby representing sugar consumers.

Whatever the reasons, governments frequently intervene in international trade. Sometimes they completely close certain markets. Sometimes they impose limits on how much can be imported from abroad. And sometimes they impose special taxes on imports. We look at each in turn.

Sanctions and Bans

In some cases, governments close down certain categories of overseas trade completely. They may do so in an attempt to further international political goals. An example from our shopping list is the Cohiba cigars. You cannot buy these directly from Cuba due to a ban on the import of Cuban goods into the United States.The sanctions began in 1962 in response to the takeover of US property by the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 extended the sanctions. US Department of State, “Title XVII—Cuban Democracy Act of 1992,” accessed March 14, 2011, http://www.state.gov/www/regions/wha/cuba/democ_act_1992.html. This policy is designed to make it harder for Cuba to function in the world economy and thus puts pressure on the Cuban government.

Governments quite often use international sanctions in an attempt to achieve political goals. These measures can be enacted by individual governments or by international bodies such as the United Nations. Currently, the international community is putting pressure on Iran because of concerns about the development of nuclear capabilities in that country.An embargo on trade with Iran was imposed by the United States in 1987. Details can be found at US Department of the Treasury, Resource Center, “Iran Sanctions,” accessed March 14, 2011, http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Pages/iran.aspx. From 1990 to 2003, there were international sanctions placed on trade with Iraq.

Governments also ban certain products from overseas for reasons of health and safety. The United States does not allow the importation of cheeses made with raw milk because it argues that such cheeses pose a health risk; thus it is difficult to find the French raw milk camembert on our shopping list. When the United Kingdom had an outbreak of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (better known as mad cow disease), many countries banned the import of beef from that country. More generally, countries have their own health and safety laws, so foreigners who wish to compete in these markets must ensure that they satisfy these standards.

Quotas

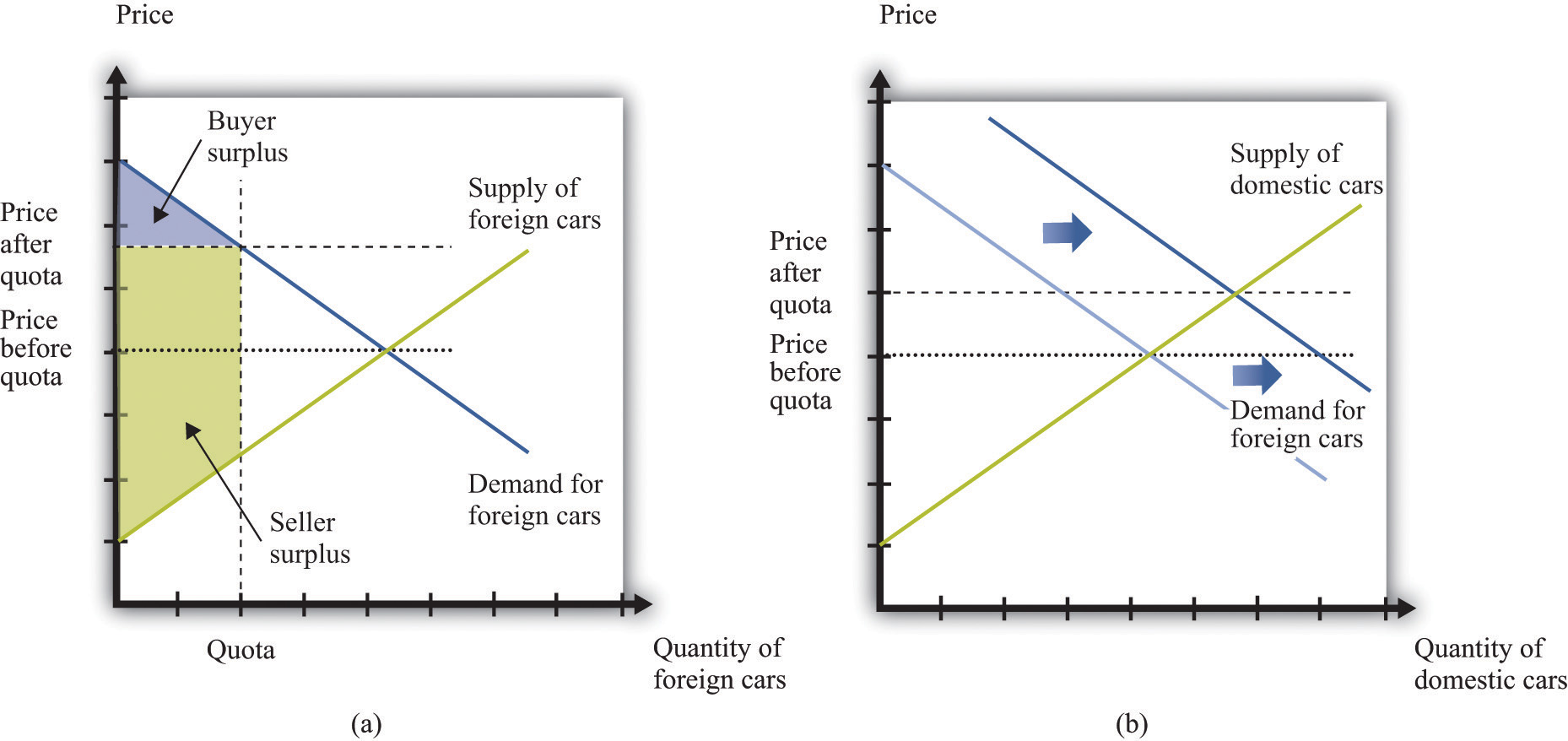

Another way in which governments frequently intervene in international transactions is by means of a quotaA quantity restriction on imports.—that is, a quantity restriction on imports. Figure 12.14 "The Effects of a Quota" gives an example of how quotas work. Suppose that Australian consumers buy both domestically produced cars (Holdens) and cars imported from the United States (Fords). These cars are not perfect substitutes for each other, so we draw a market for each kind of car. To begin with, both markets are in equilibrium where demand equals supply. Suppose that Australia were then to impose a quota on the import of Fords. The price of Fords is determined by consumers’ willingness to pay at the quantity set in the quota—that is, we can find the price by looking at the demand curve. Australian consumers must pay more for Fords. Meanwhile, the fact that fewer Fords are being sold means that Australian households will demand more Holdens. The demand curve shifts to the right. This increases the price of domestic vehicles.

Figure 12.14 The Effects of a Quota

After the imposition of the quota, the price of cars increases in the market for foreign cars (a) and the demand for domestic cars increases (b).

Who are the winners and the losers in this process? The clear winners are domestic producers of automobiles. They get to sell more cars at a higher price, and their surplus increases. Australian consumers, meanwhile, are losers. We cannot see this immediately by looking at the buyer surplus because the buyer surplus decreases in the market for foreign cars but increases in the market for domestic cars. However, we can tell that consumers are worse off because both domestic and foreign cars have become more expensive. Finally, the effects on foreign producers are in general ambiguous. They sell fewer cars but at a higher price. American producers might even benefit from the Australian quota.

In general, governments that impose quotas are transferring resources from domestic consumers to domestic producers. This illustrates the point we made earlier: the beneficiaries of this kind of policy are typically a small group—in this case, producers of Holdens. The losers are everyone who wants to buy a car. The producers are likely to have much more political influence than the consumers.

Tariffs

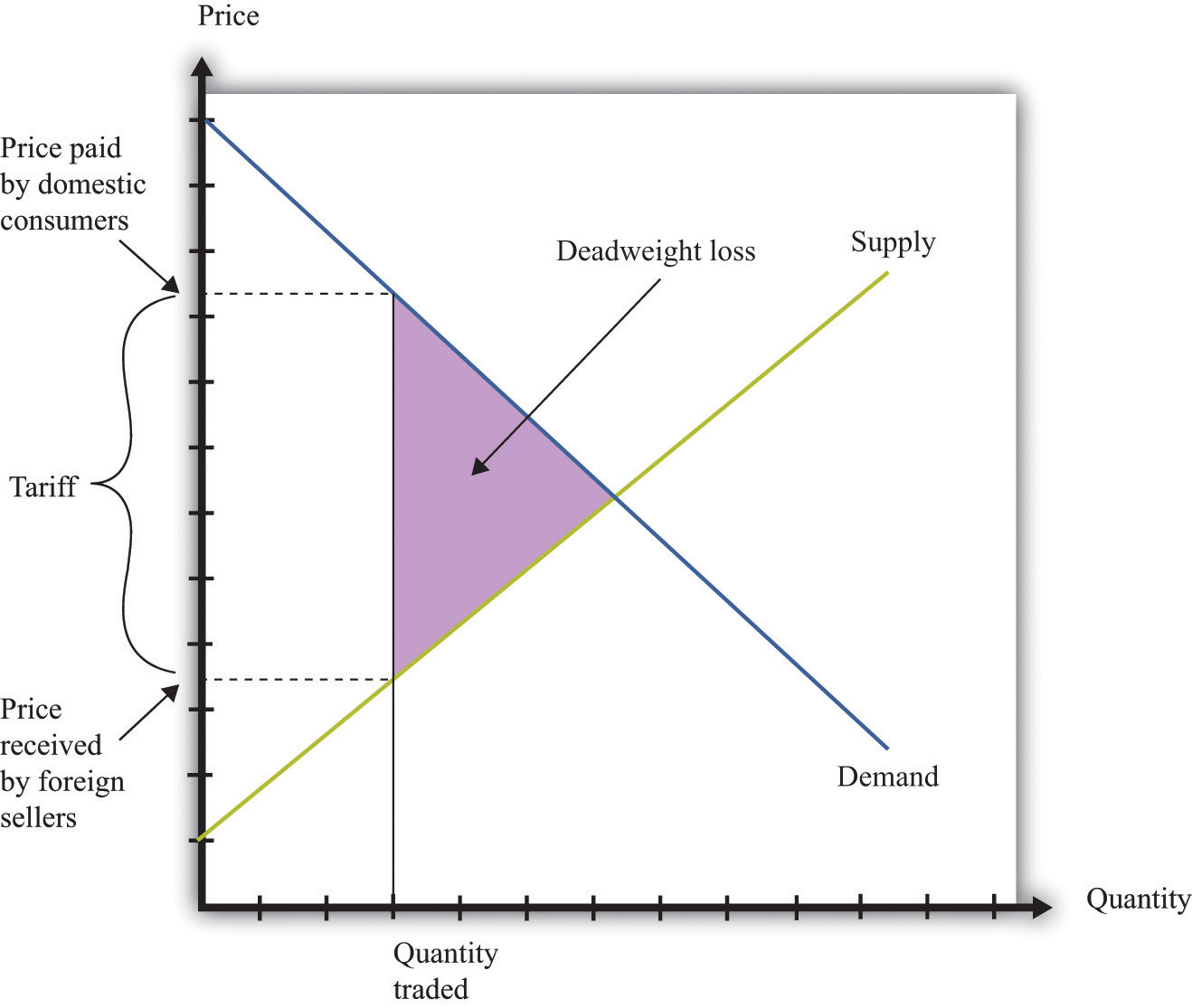

Where quotas are the equivalent of quantity restrictions, applied in the context of international trade, tariffs are the equivalent of taxes. A tariffAn amount that must be paid by someone who wishes to import that good from another country. on a good is an amount that must be paid by someone who wishes to import that good from another country. The main implication of a tariff is that the price received by foreign sellers is less than price paid by domestic consumers. We illustrate a tariff in Figure 12.15 "The Effects of a Tariff".

Figure 12.15 The Effects of a Tariff

A tariff means that there is a wedge between the price paid by domestic buyers and the price received by foreign sellers. Just as with a tax, the quantity traded is lower because some transactions are no longer worthwhile. There is a deadweight loss.

The main implications are very similar to those of a tax. Consumers are made worse off, as are foreign producers. There is a deadweight loss, as indicated in Figure 12.15 "The Effects of a Tariff". As with quotas, tariffs are often designed to protect domestic producers. Thus, as we saw when looking at a quota (Figure 12.14 "The Effects of a Quota"), a tariff on foreign goods induces a substitute toward goods produced in the domestic country. This is the law of demand at work: when the price of a good increases, the demand for substitute products will be increased.

One element that distinguishes a tariff from a quota is the collection of government revenue. When a quota is imposed, trade is limited at a particular quantity, but the government collects no revenue. Instead, as shown in Figure 12.14 "The Effects of a Quota", the surplus from the trade is distributed among buyers and sellers. When a tariff is imposed, the government collects revenue equal to the product of the tariff and the quantity traded. Comparing Figure 12.14 "The Effects of a Quota" with Figure 12.15 "The Effects of a Tariff", part of the surplus that was shared by buyers and sellers under the quota is now captured as revenue by the government. This parallels the results that we saw when looking at domestic quotas and taxes earlier in the chapter.

Key Takeaways

- There are gains to trade across countries due to comparative advantage.

- Governments place restrictions on trade for political reasons, to protect jobs, and to increase revenue by taxing trade.

- Governments may impose outright bans on trade, place limits on the quantities traded, or put taxes on trade.

Checking Your Understanding

- Looking at Table 12.1 "Beer and Tomato Production in Mexico and Guatemala", we said that Mexico had an absolute advantage in both goods, but still there were gains from trade. Change two numbers in the table so that Guatemala has an absolute advantage in both goods. Explain how each country still has a comparative advantage in your new example.

- Do the economic effects of a tariff depend on who pays it?