This is “A Walk Down Wall Street”, section 10.1 from the book Theory and Applications of Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

10.1 A Walk Down Wall Street

Learning Objectives

- What are the different types of assets traded in financial markets?

- What can you earn by owning an asset?

- What risks do you face?

Wall Street in New York City is the financial capital of the United States. There are other key financial centers around the globe: Shanghai, London, Paris, Hong Kong, and many other cities. These financial centers are places where traders come together to buy and sell assets. Beyond these physical locations, opportunities for trading assets abound on the Internet as well.

We begin the chapter by describing and explaining some of the most commonly traded assets. Ownership of an assetA resource whose ownership gives you the right to some future benefit or a stream of benefits. gives you the right to some future benefit or a stream of benefits. Very often, these benefits come in the form of monetary payments; for example, ownership of a stock gives you the right to a share of a firm’s profits. Sometimes, these benefits come in the form of a flow of services: ownership of a house gives you the right to enjoy the benefits of living in it.

Stocks

One of the first doors you find on Wall Street is called the stock exchange. The stock exchange is a place where—as the name suggests—stocks are bought and sold. A stock (or share)An asset that comes in the form of (partial) ownership of a firm. is an asset that comes in the form of (partial) ownership of a firm. The owners of a firm’s stock are called the shareholders of that firm because the stock gives them the right to a share of the firm’s profits. More precisely, shareholders receive payments whenever the board of directors of the firm decides to pay out some of the firm’s profits in the form of dividendsA payment from a firm to a firm’s shareholders based on the firm’s profits..

Some firms—for example, a small family firm like a corner grocery store—are privately owned. This means that the shares of the firm are not available for others to purchase. Other firms are publicly traded, which means that anyone is free to buy or sell their stocks. In many cases, particularly for large firms such as Microsoft Corporation or Nike, stocks are bought and sold on a minute-by-minute basis. You can find information on the prices of publicly traded stocks in newspapers or on the Internet.

Stock Market Indices

Most often, however, we hear not about individual stock prices but about baskets of stocks. The most famous basket of stocks is called the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA). Each night of the week, news reports on the radio and television and newspaper stories tell whether the value of the DJIA increased or decreased that day. The DJIA is more than a century old—it started in 1896—and is a bundle of 30 stocks representing some of the most significant firms in the US economy. Its value reflects the prices of these stocks. Very occasionally, one firm will be dropped from the index and replaced with another, reflecting changes in the economy.You can learn more about the DJIA if you go to NYSE Euronext, “Dow Jones Industrial Average,” accessed March 14, 2011,http://www.nyse.com/marketinfo/indexes/dji.shtml.

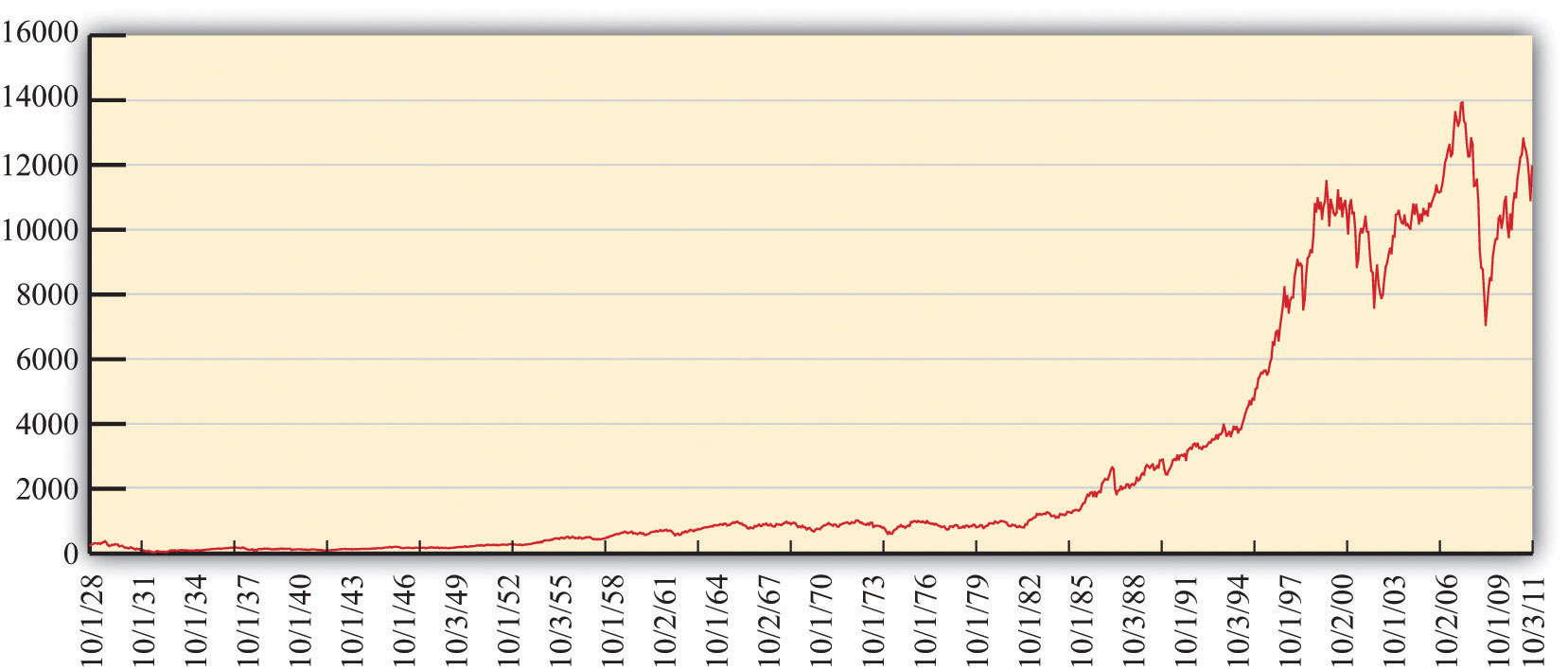

Figure 10.3 The DJIA: October 1928 to July 2007

This figure shows the closing prices for the DJIA between 1928 and 2010.

Source: The chart is generated from http://finance.yahoo.com/q?s=^DJI.

Figure 10.3 "The DJIA: October 1928 to July 2007" shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average from 1928 to 2011. Over that period, the index rose from about 300 to about 12,500, which is an average growth rate of about 4.5 percent per year. You can see that this growth was not smooth, however. There was a big decrease at the very beginning, known as the stock market crash of 1929. There was another very significant drop in October 1987. Even though the 1929 crash looks smaller than the 1987 decrease, the 1929 crash was much more severe. In 1929, the stock market lost about half its value and took many years to recover. In 1987, the market lost only about 25 percent of its value and recovered quite quickly.

One striking feature of Figure 10.3 "The DJIA: October 1928 to July 2007" is the very rapid growth in the DJIA in the 1990s and the subsequent decrease around the turn of the millennium. The 1990s saw the so-called Internet boom, when there was a lot of excitement about new companies taking advantage of new technologies. Some of these companies, such as Amazon, went on to be successful, but most others failed. As investors came to recognize that most of these new companies would not make money, the market fell in value. There was another rise in the market during the 2000s, followed by a substantial fall during the global financial crisis that began around 2008. Very recently, the market has recovered again.

If these ups and downs in the DJIA were predictable, it would be easy to make money on Wall Street. Suppose you knew the DJIA would increase 10 percent next month. You would buy the stocks in the average now, hold them for a month, and sell them for an easy 10 percent profit. If you knew the DJIA would decrease next month, you could still make money. If you currently owned DJIA stocks, you could sell them and then buy them back after the price decreased. Even if you don’t own these stocks right now, there is still a way of selling first and buying later. You can sell (at today’s high price) a promise to deliver the stocks in a month’s time. Then you buy the stocks after the price has decreased. This is called a forward sale. If this sounds as if it is too easy a way to make money, that’s because it is. The ups and downs in the DJIA are not perfectly predictable, so there are no easy profit opportunities of the kind we just described. We have more to say about this later in the chapter.

Although the DJIA is the most closely watched stock market index, many others are also commonly reported. The Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) is another important index. As the name suggests, it includes 500 firms, so it is more representative than the DJIA. If you want to understand what is happening to stock prices in general, you are better off looking at the S&P 500 than at the DJIA. The Nasdaq is another index, consisting of the stocks traded in an exchange that specializes in technology-based firms.

We mentioned earlier that the DJIA has increased by almost 5 percent per year on average since 1928. On the face of it, this seems like a fairly respectable level of growth. Yet we must be careful. The DJIA and other indices are averages of stock prices, which are measured in dollar terms. To understand what has happened to the stock market in real terms, we need to adjust for inflation. Between 1928 and 2007, the price level rose by 2.7 percent per year on average. The average growth in the DJIA, adjusted for inflation, was thus 4.8 percent − 2.7 percent = 2.1 percent.

The Price of a Stock

As a shareholder, there are two ways in which you can earn income from your stock. First, as we have explained, firms sometimes choose to pay out some of their income in the form of dividends. If you own some shares and the company declares it will pay a dividend, either you will receive a check in the mail or the company will automatically reinvest your dividend and give you extra shares. But there is no guarantee that a company will pay a dividend in any given year.

The second way you can earn income is through capital gainsIncome from an increase in the price of an asset.. Suppose you own a stock whose price has gone up. If that happens, you can—if you want—sell your stock and make a profit on the difference between the price you paid for the stock and the higher price you sold it for. Capital gains are the income you obtain from the increase in the price of an asset. (If the asset decreases in value, you instead incur a capital loss.)

To see how this works, suppose you buy, for $100, a single share of a company whose stock is trading on an exchange. In exchange for $100, you now have a piece of paper indicating that you own a share of a firm. After a year has gone by, imagine that the firm declares it will pay out dividends of $6.00 per share. Also, at the end of the year, suppose the price of the stock has increased to $105.00. You decide to sell at that price. So with your $100.00, you received $111.00 at the end of the year for an annual return of 11 percent:

(We have used the term return a few times. We will give a more precise definition of this term later. At present, you just need to know that it is the amount you obtain, in percentage terms, from holding an asset for a year.)

Suppose that a firm makes some profits but chooses not to pay out a dividend. What does it do with those funds? They are called retained earnings and are normally used to finance business operations. For example, a firm may take some of its profits to build a new factory or buy new machines. If a firm is being managed well, then those expenditures should allow a firm to make higher profits in the future and thus be able to pay out more dividends at a later date. Presuming once again that the firm is well managed, retained earnings should translate into extra dividends that will be paid in the future.

Furthermore, if people expect that a firm will pay higher dividends in the future, then they should be willing to pay more for shares in that firm today. This increase in demand for a firm’s shares will cause the share price to increase. So if a firm earns profits but does not pay a dividend, you should expect to get some capital gain instead. We come back to this idea later in the chapter and explain more carefully the connection between a firm’s dividend payments and the price of its stock.

The Riskiness of Stocks

Figure 10.3 "The DJIA: October 1928 to July 2007" reminds us that stock prices decrease as well as increase. If you choose to buy a stock, it is always possible its price will fall, in which case you suffer a capital loss rather than obtain a capital gain. The riskiness of stocks comes from the fact that the underlying fortunes of a firm are uncertain. Some firms are successful and earn high profits, which means that they are able to pay out large dividends—either now or in the future. Other firms are unsuccessful through either bad luck or bad management, and do not pay dividends. Particularly unsuccessful firms go bankrupt; shares in such a firm become close to worthless. When you buy a share in a firm, you have the chance to make money, but you might lose money as well.

Bonds

Wall Street is also home to many famous financial institutions, such as Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, and many others. These firms act as the financial intermediaries that link borrowers and lenders. If desired, you could use one of these firms to help you buy and sell shares on the stock exchange. You can also go to one of these firms to buy and sell bonds. A bondA promise to make cash payments to a bondholder at predetermined dates (such as every year) until the maturity date. is a promise to make cash payments (the couponThe cash payments paid to a bondholder.) to a bondholder at predetermined dates (such as every year) until the maturity date. At the maturity dateThe date of final payment of principal and interest on a bond., a final payment is made to a bondholder. Firms and governments that are raising funds issue bonds. A firm may wish to buy some new machinery or build a new plant, so it needs to borrow to finance this investment. Or a government might issue bonds to finance the construction of a road or a school.

The easiest way to think of a bond is that it is the asset associated with a loan. Here is a simple example. Suppose you loan a friend $100 for a year at a 6 percent interest rate. This means that the friend has agreed to pay you $106 a year from now. Another way to think of this agreement is that you have bought, for a price of $100, an asset that entitles you to $106 in a year’s time. More generally (as the definition makes clear), a bond may entitle you to an entire schedule of repayments.

The Riskiness of Bonds

Bonds, like stocks, are risky.

- The coupon payments of a bond are almost always specified in dollar terms. This means that the real value of these payments depends on the inflation rate in an economy. Higher inflation means that the value of a bond has less worth in real terms.

- Bonds, like stocks, are also risky because of the possibility of bankruptcy. If a firm borrows money but then goes bankrupt, bondholders may end up not being repaid. The extent of this risk depends on who issues the bond. Government bonds usually carry a low risk of bankruptcy. It is unlikely that a government will default on its debt obligations, although it is not impossible: Iceland, Ireland, Greece, and Portugal, for example, have recently been at risk of default. In the case of bonds issued by firms, the riskiness obviously depends on the firm. An Internet start-up firm operated from your neighbor’s garage is more likely to default on its loans than a company like the Microsoft Corporation. There are companies that evaluate the riskiness of firms; the ratings provided by these companies have a tremendous impact on the cost that firms incur when they borrow.

Inflation does not have the same effect on stocks as it does on bonds. If prices increase, then the fixed nominal payments of a bond unambiguously become less valuable. But if prices increase, firms will typically set higher nominal prices for their products, earn higher nominal profits, and pay higher nominal dividends. So inflation does not, in and of itself, make stocks less valuable.

Toolkit: Section 31.8 "Correcting for Inflation"

You can review the meaning and calculation of the inflation rate in the toolkit.

One way to see the differences in the riskiness of bonds is to look at the cost of issuing bonds for different groups of borrowers. Generally, the rate at which the US federal government can borrow is much lower than the rate at which corporations borrow. As the riskiness of corporations increases, so does the return they must offer to compensate investors for this risk.

Real Estate and Cars

As you continue to walk down the street, you are somewhat surprised to see a real estate office and a car dealership on Wall Street. (But this is a fictionalized Wall Street, so why not?) Real estate is another kind of asset. Suppose, for example, that you purchase a home and then rent it out. The rental payments you receive are analogous to the dividends from a stock or the coupon payments on a bond: they are a flow of money you receive from ownership of the asset.

Real estate, like other assets, is risky. The rent you can obtain may increase or decrease, and the price of the home can also change over time. The fact that housing is a significant—and risky—financial asset became apparent in the global financial crisis that began in 2007. There were many aspects of that crisis, but an early trigger of the crisis was the fact that housing prices decreased in the United States and around the world.

If you buy a home and live in it yourself, then you still receive a flow of services from your asset. You don’t receive money directly, but you receive money indirectly because you don’t have to pay rent to live elsewhere. You can think about measuring the value of the flow of services as rent you are paying to yourself.

Our fictional Wall Street also has a car dealership—not only because all the financial traders need somewhere convenient to buy their BMWs but also because cars, like houses, are an asset. They yield a flow of services, and their value is linked to that service flow.

The Foreign Exchange Market

Further down the street, you see a small store listing a large number of different three-letter symbols: BOB, JPY, CND, EUR, NZD, SEK, RUB, SOS, ADF, and many others. Stepping inside to inquire, you learn that that, in this store, they buy and sell foreign currencies. (These three-letter symbols are the currency codes established by the International Organization for Standardization (http://www.iso.org/iso/home.htm). Most of the time, the first two letters refer to the country, and the third letter is the initial letter of the currency unit. Thus, in international dealings, the US dollar is referenced by the symbol USD.)

Foreign currencies are another asset—a simple one to understand. The return on foreign currency depends on how the exchange rate changes over the course of a year. The (nominal) exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another. For example, if it costs US$2 to purchase €1, then the exchange rate for these two currencies is 2. An exchange rate can be looked at in two directions. If the dollar-price of a euro is 2, then the euro price of a dollar is 0.5: with €0.5, you can buy US$1.

Suppose that the exchange rate this year is US$2 to the euro, and suppose you have US$100. You buy €50 and wait a year. Now suppose that next year the exchange rate is US$2.15 to the euro. With your €50, you can purchase US$107.50 (because US$(50 × 2.15) = US$107.50). Your return on this asset is 7.5 percent. Holding euros was a good investment because the dollar became less valuable relative to the euro. Of course, the dollar might increase in value instead. Holding foreign currency is risky, just like holding all the other assets we have considered.The currency market is also discussed in Chapter 8 "Why Do Prices Change?".

The foreign exchange market brings together suppliers and demanders of different currencies in the world. In these markets, one currency is bought using another. The law of demand holds: as the price of a foreign currency increases, the quantity demanded of that currency decreases. Likewise, as the price of a foreign currency increases, the quantity supplied of that currency increases. Exchange rates are determined just like other prices, by the interaction of supply and demand. At the equilibrium exchange rate, the quantity of the currency supplied equals the quantity demanded. Shifts in the supply or demand for a currency lead to changes in the exchange rate.

Toolkit: Section 31.20 "Foreign Exchange Market"

You can review the foreign exchange market and the exchange rate in the toolkit.

Foreign Assets

Having recently read about the large returns on the Shanghai stock exchange and having seen that you can buy Chinese currency (the yuan, which has the international code CNY), you might wonder whether you can buy shares on the Shanghai stock exchange. In general, you are not restricted to buying assets in your home country. After all, there are companies and governments around the world who need to finance projects of various forms. Financial markets span the globe, so the bonds issued by these companies and governments can be purchased almost anywhere. You can buy shares in Australian firms, Japanese government bonds, or real estate in Italy.Some countries have restrictions on asset purchases by noncitizens—for example, it is not always possible for foreigners to buy real estate. But such restrictions notwithstanding, the menu of assets from which you can choose is immense. Indeed, television, newspapers, and the Internet report on the behavior of both US stock markets and those worldwide, such as the FTSE 100 on the London stock exchange, the Hang Seng index on the Hong Kong stock exchange, the Nikkei 225 index on the Tokyo stock exchange, and many others.

You could buy foreign assets from one of the big financial firms that you visited earlier. It will be happy to buy foreign stocks or bonds on your behalf. Of course, if you choose to buy stocks or bonds associated with foreign companies or governments, you face all the risks associated with buying domestic stocks and bonds. The dividends are uncertain, there might be inflation in the foreign country, the price of the asset might change, and so on. In addition, you face exchange rate risk. If you purchase a bond issued in Mexico, you don’t know what exchange rate you will face in the future for converting pesos to your home currency.

You may feel hesitant about investing in other countries. You are not alone in this. Economists have detected something they call home bias. All else being equal, investors are more likely to buy assets issued by corporations and governments in their own country rather than abroad.

A Casino

Toward the end of your walk, you are particularly surprised to see a casino. Stepping inside, you see a casino floor, such as you might find in Las Vegas, Monaco, or Macau near Hong Kong. You are confronted with a vast array of betting opportunities.

The first one you come across is a roulette wheel. The rules are simple enough. You place your chip on a number. After the wheel is spun, you win if—and only if—you guessed the number that is called. There is no skill—only luck. Nearby are the blackjack tables where a version of 21 is played. In contrast to roulette, blackjack requires some skill. As a gambler in blackjack, you have to make choices about taking cards or not. The objective is to get cards whose sum is as high as possible without going over 21. If you do go over 21, you lose. If the dealer goes over 21 and you don’t, you win. If neither of you goes over 21, then the winner is the one with the highest total. There is skill involved in deciding whether or not to take a card. There is also a lot of luck involved through the draw of the cards.

You always thought of stocks and bonds as serious business. Yet, as you watch the players on the casino floor, you come to realize that it might not be so peculiar to see a casino on Wall Street. Perhaps there are some similarities between risking money at a gambling table and investing in stocks, bonds, or other assets. As this chapter progresses, you will see that there are some similarities between trading in financial assets and gambling in a casino. But you will learn that there are important differences as well.

Key Takeaways

- Many different types of assets, such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and foreign currency, are traded in financial markets.

- Your earnings from owning an asset depend on the type of asset. If you own a stock, then you are paid dividends and also receive a capital gain or incur a capital loss from selling the asset. If you own real estate, then you have a flow of rental payments from the property and also receive a capital gain or incur a capital loss from selling the asset.

- Risks also depend on the type of asset. If you own a bond issued by a company, then you bear the risk of that company going bankrupt and being unable to pay off its debt.

Checking Your Understanding

- If you live in a house rather than rent it, do you still get some benefits from ownership? How would these benefits compare with the income you could receive if you rented out the house?

- What assets are subject to the risk of bankruptcy?