This is “Easements: Rights in the Lands of Others”, section 14.3 from the book The Legal Environment and Government Regulation of Business (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.3 Easements: Rights in the Lands of Others

Learning Objectives

- Explain the difference between an easement and a license.

- Describe the ways in which easements can be created.

Definition

An easementAn interest in land created by agreement that permits one person to make use of another’s estate. is an interest in land created by agreement that permits one person to make use of another’s estate. This interest can extend to a profit, the taking of something from the other’s land. Though the common law once distinguished between an easement and profit, today the distinction has faded, and profits are treated as a type of easement. An easement must be distinguished from a mere licenseAs opposed to an easement, a license is personal to the grantee and is not assignable., which is permission, revocable at the will of the owner, to make use of the owner’s land. An easement is an estate; a license is personal to the grantee and is not assignable.

The two main types of easements are affirmative and negative. An affirmative easement gives a landowner the right to use the land of another (e.g., crossing it or using water from it), while a negative easementAn easement that prohibits the owner of the land from using his or her land in ways that would affect the holder of the easement., by contrast, prohibits the landowner from using his land in ways that would affect the holder of the easement. For example, the builder of a solar home would want to obtain negative easements from neighbors barring them from building structures on their land that would block sunlight from falling on the solar home. With the growth of solar energy, some states have begun to provide stronger protection by enacting laws that regulate one’s ability to interfere with the enjoyment of sunlight. These laws range from a relatively weak statute in Colorado, which sets forth rules for obtaining easements, to the much stronger statute in California, which says in effect that the owner of a solar device has a vested right to continue to receive the sunlight.

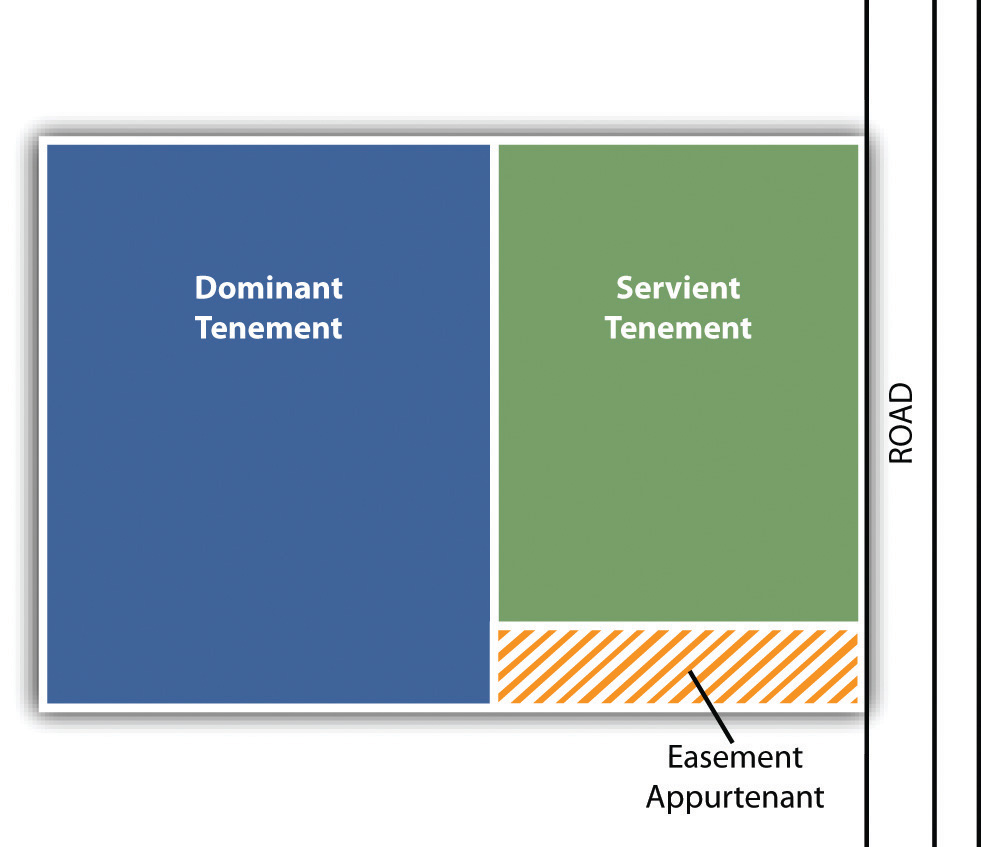

Another important distinction is made between easements appurtenant and easements in gross. An easement appurtenantAn easement that benefits the owner of adjacent land. The easement is thus appurtenant to the holder’s land. benefits the owner of adjacent land. The easement is thus appurtenant to the holder’s land. The benefited land is called the dominant tenementThe land that benefits from an easement., and the burdened land—that is, the land subject to the easement—is called the servient tenementThe burdened land—that is, the land subject to the easement. (see Figure 14.3 "Easement Appurtenant"). An easement in gross is granted independent of the easement holder’s ownership or possession of land. It is simply an independent right—for example, the right granted to a local delivery service to drive its trucks across a private roadway to gain access to homes at the other end.

Figure 14.3 Easement Appurtenant

Unless it is explicitly limited to the grantee, an easement appurtenant “runs with the land.” That is, when the dominant tenement is sold or otherwise conveyed, the new owner automatically owns the easement. A commercial easement in gross may be transferred—for instance, easements to construct pipelines, telegraph and telephone lines, and railroad rights of way. However, most noncommercial easements in gross are not transferable, being deemed personal to the original owner of the easement. Rochelle sells her friend Mrs. Nanette—who does not own land adjacent to Rochelle—an easement across her country farm to operate skimobiles during the winter. The easement is personal to Mrs. Nanette; she could not sell the easement to anyone else.

Creation

Easements may be created by express agreement, either in deeds or in wills. The owner of the dominant tenement may buy the easement from the owner of the servient tenement or may reserve the easement for himself when selling part of his land. But courts will sometimes allow implied easements under certain circumstances. For instance, if the deed refers to an easement that bounds the premises—without describing it in any detail—a court could conclude that an easement was intended to pass with the sale of the property.

An easement can also be implied from prior use. Suppose a seller of land has two lots, with a driveway connecting both lots to the street. The only way to gain access to the street from the back lot is to use the driveway, and the seller has always done so. If the seller now sells the back lot, the buyer can establish an easement in the driveway through the front lot if the prior use was (1) apparent at the time of sale, (2) continuous, and (3) reasonably necessary for the enjoyment of the back lot. The rule of implied easements through prior use operates only when the ownership of the dominant and servient tenements was originally in the same person.

Use of the Easement

The servient owner may use the easement—remember, it is on or under or above his land—as long as his use does not interfere with the rights of the easement owner. Suppose you have an easement to walk along a path in the woods owned by your neighbor and to swim in a private lake that adjoins the woods. At the time you purchased the easement, your neighbor did not use the lake. Now he proposes to swim in it himself, and you protest. You would not have a sound case, because his swimming in the lake would not interfere with your right to do so. But if he proposed to clear the woods and build a mill on it, obliterating the path you took to the lake and polluting the lake with chemical discharges, then you could obtain an injunction to bar him from interfering with your easement.

The owner of the dominant tenement is not restricted to using his land as he was at the time he became the owner of the easement. The courts will permit him to develop the land in some “normal” manner. For example, an easement on a private roadway for the benefit of a large estate up in the hills would not be lost if the large estate were ultimately subdivided and many new owners wished to use the roadway; the easement applies to the entire portion of the original dominant tenement, not merely to the part that abuts the easement itself. However, the owner of an easement appurtenant to one tract of land cannot use the easement on another tract of land, even if the two tracts are adjacent.

Key Takeaway

An easement appurtenant runs with the land and benefits the dominant tenement, burdening the servient tenement. An easement, generally, has a specific location or description within or over the servient tenement. Easements can be created by deed, by will, or by implication.

Exercise

- Beth Delaney owns property next to Kerry Plemmons. The deed to Delaney’s property notes that she has access to a well on the Plemmons property “to obtain water for household use.” The well has been dry for many generations and has not been used by anyone on the Plemmons property or the Delaney property for as many generations. The well predated Plemmons’s ownership of the property; as the servient tenement, the Plemmons property was burdened by this easement dating back to 1898. Plemmons hires a company to dig a very deep well near one of his outbuildings to provide water for his horses. The location is one hundred yards from the old well. Does the Delaney property have any easement to use water from the new well?