This is “The Acceptance”, section 9.3 from the book The Legal Environment and Business Law (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

9.3 The Acceptance

Learning Objectives

- Define acceptance.

- Understand who may accept an offer.

- Know when the acceptance is effective.

- Recognize when silence is acceptance.

General Definition of Acceptance

To result in a legally binding contract, an offer must be accepted by the offeree. Just as the law helps define and shape an offer and its duration, so the law governs the nature and manner of acceptanceAssent to the terms of the offer.. The Restatement defines acceptance of an offer as “a manifestation of assent to the terms thereof made by the offeree in a manner invited or required by the offer.”Restatement (Second) of Contracts, Section 24.The assent may be either by the making of a mutual promise or by performance or partial performance. If there is doubt about whether the offer requests a return promise or a return act, the Restatement, Section 32, provides that the offeree may accept with either a promise or performance. The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) also adopts this view; under Section 2-206(1)(a), “an offer to make a contract shall be construed as inviting acceptance in any manner and by any medium reasonable in the circumstances” unless the offer unambiguously requires a certain mode of acceptance.

Who May Accept?

The identity of the offeree is usually clear, even if the name is unknown. The person to whom a promise is made is ordinarily the person whom the offeror contemplates will make a return promise or perform the act requested. But this is not invariably so. A promise can be made to one person who is not expected to do anything in return. The consideration necessary to weld the offer and acceptance into a legal contract can be given by a third party. Under the common law, whoever is invited to furnish consideration to the offeror is the offeree, and only an offeree may accept an offer. A common example is sale to a minor. George promises to sell his automobile to Bartley, age seventeen, if Bartley’s father will promise to pay $3,500 to George. Bartley is the promisee (the person to whom the promise is made) but not the offeree; Bartley cannot legally accept George’s offer. Only Bartley’s father, who is called on to pay for the car, can accept, by making the promise requested. And notice what might seem obvious: a promise to perform as requested in the offer is itself a binding acceptance.

When Is Acceptance Effective?

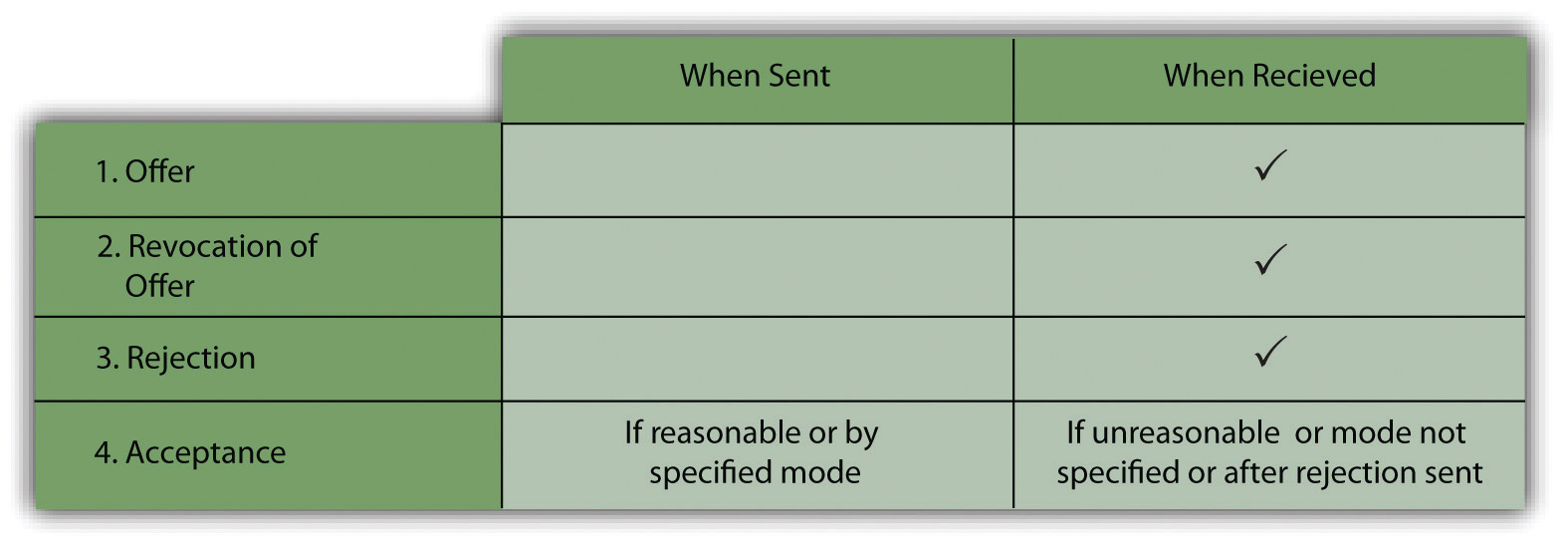

As noted previously, an offer, a revocation of the offer, and a rejection of the offer are not effective until received. The same rule does not always apply to the acceptance.

Instantaneous Communication

Of course, in many instances the moment of acceptance is not in question: in face-to-face deals or transactions negotiated by telephone, the parties extend an offer and accept it instantaneously during the course of the conversation. But problems can arise in contracts negotiated through correspondence.

Stipulations as to Acceptance

One common situation arises when the offeror stipulates the mode of acceptance (e.g., return mail, fax, or carrier pigeon). If the offeree uses the stipulated mode, then the acceptance is deemed effective when sent. Even though the offeror has no knowledge of the acceptance at that moment, the contract has been formed. Moreover, according to the Restatement, Section 60, if the offeror says that the offer can be accepted only by the specified mode, that mode must be used. (It is said that “the offeror is the master of the offer.”)

If the offeror specifies no particular mode, then acceptance is effective when transmitted, as long as the offeree uses a reasonable method of acceptance. It is implied that the offeree can use the same means used by the offeror or a means of communication customary to the industry.

The “Mailbox Rule”

The use of the postal service is customary, so acceptances are considered effective when mailed, regardless of the method used to transmit the offer. Indeed, the so-called mailbox ruleCommon-law rule that acceptance is effective when dropped in mail. has a lineage tracing back more than one hundred years to the English courts.Adams v. Lindsell, 1 Barnewall & Alderson 681 (K.B. 1818).

The mailbox rule may seem to create particular difficulties for people in business, since the acceptance is effective even though the offeror is unaware of the acceptance, and even if the letter is lost and never arrives. But the solution is the same as the rationale for the rule. In contracts negotiated through correspondence, there will always be a burden on one of the parties. If the rule were that the acceptance is not effective until received by the offeror, then the offeree would be on tenterhooks, rather than the other way around, as is the case with the present rule. As between the two, it seems fairer to place the burden on the offeror, since he or she alone has the power to fix the moment of effectiveness. All the offeror need do is specify in the offer that acceptance is not effective until received.

In all other cases—that is, when the offeror fails to specify the mode of acceptance and the offeree uses a mode that is not reasonable—acceptance is deemed effective only when received.

Acceptance “Outruns” Rejection

When the offeree sends a rejection first and then later transmits a superseding acceptance, the “effective when received” rule also applies. Suppose a seller offers a buyer two cords of firewood and says the offer will remain open for a week. On the third day, the buyer writes the seller, rejecting the offer. The following evening, the buyer rethinks his firewood needs, and on the morning of the fifth day, he sends an e-mail accepting the seller’s terms. The previously mailed letter arrives the following day. Since the letter had not yet been received, the offer had not been rejected. For there to be a valid contract, the e-mailed acceptance must arrive before the mailed rejection. If the e-mail were hung up in cyberspace, although through no fault of the buyer, so that the letter arrived first, the seller would be correct in assuming the offer was terminated—even if the e-mail arrived a minute later. In short, where “the acceptance outruns the rejection” the acceptance is effective. See Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1

When Is Communication Effective?

Electronic Communications

Electronic communications have, of course, become increasingly common. Many contracts are negotiated by e-mail, accepted and “signed” electronically. Generally speaking, this does not change the rules. The Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA)A US law generally making electronic contracting valid and the contracts enforceable. was promulgated (i.e., disseminated for states to adopt) in 1999. It is one of a number of uniform acts, like the Uniform Commercial Code. As of June 2010, forty-seven states and the US Virgin Islands had adopted the statute. The introduction to the act provides that “the purpose of the UETA is to remove barriers to electronic commerce by validating and effectuating electronic records and signatures.”The National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (1999) (Denver: National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, 1999), accessed March 29, 2011, http://www.law.upenn.edu/bll/archives/ulc/fnact99/1990s/ueta99.pdf. In general, the UETA provides the following:

- A record or signature may not be denied legal effect or enforceability solely because it is in electronic form.

- A contract may not be denied legal effect or enforceability solely because an electronic record was used in its formation.

- If a law requires a record to be in writing, an electronic record satisfies the law.

- If a law requires a signature, an electronic signature satisfies the law.

The UETA, though, doesn’t address all the problems with electronic contracting. Clicking on a computer screen may constitute a valid acceptance of a contractual offer, but only if the offer is clearly communicated. In Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp., customers who had downloaded a free online computer program complained that it effectively invaded their privacy by inserting into their machines “cookies”; they wanted to sue, but the defendant said they were bound to arbitration.Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp., 306 F.3d 17 (2d Cir. 2002). They had clicked on the Download button, but hidden below it were the licensing terms, including the arbitration clause. The federal court of appeals held that there was no valid acceptance. The court said, “We agree with the district court that a reasonably prudent Internet user in circumstances such as these would not have known or learned of the existence of the license terms before responding to defendants’ invitation to download the free software, and that defendants therefore did not provide reasonable notice of the license terms. In consequence, the plaintiffs’ bare act of downloading the software did not unambiguously manifest assent to the arbitration provision contained in the license terms.”

If a faxed document is sent but for some reason not received or not noticed, the emerging law is that the mailbox rule does not apply. A court would examine the circumstances with care to determine the reason for the nonreceipt or for the offeror’s failure to notice its receipt. A person has to have fair notice that his or her offer has been accepted, and modern communication makes the old-fashioned mailbox rule—that acceptance is effective upon dispatch—problematic.See, for example, Clow Water Systems Co. v. National Labor Relations Board, 92 F.3d 441 (6th Cir. 1996).

Silence as Acceptance

General Rule: Silence Is Not Acceptance

Ordinarily, for there to be a contract, the offeree must make some positive manifestation of assent to the offeror’s terms. The offeror cannot usually word his offer in such a way that the offeree’s failure to respond can be construed as an acceptance.

Exceptions

The Restatement, Section 69, gives three situations, however, in which silence can operate as an acceptance. The first occurs when the offeree avails himself of services proffered by the offeror, even though he could have rejected them and had reason to know that the offeror offered them expecting compensation. The second situation occurs when the offer states that the offeree may accept without responding and the offeree, remaining silent, intends to accept. The third situation is that of previous dealings, in which only if the offeree intends not to accept is it reasonable to expect him to say so.

As an example of the first type of acceptance by silence, assume that a carpenter happens by your house and sees a collapsing porch. He spots you in the front yard and points out the deterioration. “I’m a professional carpenter,” he says, “and between jobs. I can fix that porch for you. Somebody ought to.” You say nothing. He goes to work. There is an implied contract, with the work to be done for the carpenter’s usual fee.

To illustrate the second situation, suppose that a friend has left her car in your garage. The friend sends you a letter in which she offers you the car for $4,000 and adds, “If I don’t hear from you, I will assume that you have accepted my offer.” If you make no reply, with the intention of accepting the offer, a contract has been formed.

The third situation is illustrated by Section 9.4.3 "Silence as Acceptance", a well-known decision made by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. when he was sitting on the Supreme Court of Massachusetts.

Key Takeaway

Without an acceptance of an offer, no contract exists, and once an acceptance is made, a contract is formed. If the offeror stipulates how the offer should be accepted, so be it. If there is no stipulation, any reasonable means of communication is good. Offers and revocations are usually effective upon receipt, while an acceptance is effective on dispatch. The advent of electronic contracting has caused some modification of the rules: courts are likely to investigate the facts surrounding the exchange of offer and acceptance more carefully than previously. But the nuances arising because of the mailbox rule and acceptance by silence still require close attention to the facts.

Exercises

- Rudy puts this poster, with a photo of his dog, on utility poles around his neighborhood: “$50 reward for the return of my lost dog.” Carlene doesn’t see the poster, but she finds the dog and, after looking at the tag on its collar, returns the dog to Rudy. As she leaves his house, her eye falls on one of the posters, but Rudy declines to pay her anything. Why is Rudy correct that Carlene has no legal right to the reward?

- How has the UCC changed the common law’s mirror image rule, and why?

- When is an offer generally said to be effective? A rejection of an offer? A counteroffer?

- How have modern electronic communications affected the law of offer and acceptance?

- When is silence considered an acceptance?