This is “Bailments and the Storage, Shipment, and Leasing of Goods”, chapter 12 from the book The Legal Environment and Advanced Business Law (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 12 Bailments and the Storage, Shipment, and Leasing of Goods

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should understand the following:

- What the elements of a bailment are

- What the bailee’s liability is

- What the bailor’s liability is

- What other rights and duties—compensation, bailee’s liens, casualty to goods—arise

- What special types of bailments are recognized: innkeepers, warehousing

- What rules govern the shipment of goods

- How commodity paper is negotiated and transferred

12.1 Introduction to Bailment Law

Learning Objectives

- Understand what a bailment is, and why the law of bailment is important.

- Recognize how bailments compare with sales.

- Point out the elements required to create a bailment.

Finally, we turn to the legal relationships that buyers and sellers have with warehousers and carriers—the parties responsible for physically transferring goods from seller to buyer. This topic introduces a new branch of law—that of bailments; we’ll examine it before turning directly to warehousers and carriers.

Overview of Bailments

A bailmentA delivery of goods to one who does not have title. is the relationship established when someone entrusts his property temporarily to someone else without intending to give up title. Although bailment has often been said to arise only through a contract, the modern definition does not require that there be an agreement. One widely quoted definition holds that a bailment is “the rightful possession of goods by one who is not the owner. It is the element of lawful possession, however created, and the duty to account for the thing as the property of another, that creates the bailment, regardless of whether such possession is based upon contract in the ordinary sense or not.”Zuppa v. Hertz, 268 A.2d 364 (N.J. 1970).

The word bailment derives from a Latin verb, bajulare, meaning “to bear a burden,” and then from French, bailler, which means “to deliver” (i.e., into the hands or possession of someone). The one who bails out a boat, filling a bucket and emptying it overboard, is a water-bearer. The one who bails someone out of jail takes on the burden of ensuring that the one sprung appears in court to stand trial; he also takes on the risk of loss of bond money if the jailed party does not appear in court. The one who is a baileeThe person to whom property is delivered to hold in bailment. takes on the burden of being responsible to return the goods to their owner.

The law of bailments is important to virtually everyone in modern society: anyone who has ever delivered a car to a parking lot attendant, checked a coat in a restaurant, deposited property in a safe-deposit box, rented tools, or taken items clothes or appliance in to a shop for repair. In commercial transactions, bailment law governs the responsibilities of warehousers and the carriers, such as UPS and FedEx, that are critical links in the movement of goods from manufacturer to the consumer. Bailment law is an admixture of common law (property and tort), state statutory law (in the Uniform Commercial Code; UCC), federal statutory law, and—for international issues—treaty.Here is a link to a history of bailment law: Globusz Publishing, “Lecture v. the Bailee at Common Law,” accessed March 1, 2011, http://www.globusz.com/ebooks/CommonLaw/00000015.htm.

Bailments Compared with Sales

Bailment versus Sales

In a sale, the buyer acquires title and must pay for the goods. In a bailment, the bailee acquires possession and must return the identical object. In most cases the distinction is clear, but difficult borderline cases can arise. Consider the sad case of the leased cows: Carpenter v. Griffen (N.Y. 1841). Carpenter leased a farm for five years to Spencer. The lease included thirty cows. At the end of the term, Spencer was to give Carpenter, the owner, “cows of equal age and quality.” Unfortunately, Spencer fell into hard times and had to borrow money from one Griffin. When the time came to pay the debt, Spencer had no money, so Griffin went to court to levy against the cows (i.e., he sought a court order giving him the cows in lieu of the money owed). Needless to say, this threatened transfer of the cows upset Carpenter, who went to court to stop Griffin from taking the cows. The question was whether Spencer was a bailee, in which case the cows would still belong to Carpenter (and Griffin could not levy against them), or a purchaser, in which case Spencer would own the cows and Griffin could levy against them. The court ruled that title had passed to Spencer—the cows were his. Why? The court reasoned that Spencer was not obligated to return the identical cows to Carpenter, hence Spencer was not a bailee.Carpenter v. Spencer & Griffin, 37 Am. Dec. 396 (N.Y. 1841). Section 2-304(1) of the UCC confirms this position, declaring that whenever the price of a sale is payable in goods, each party is a seller of the goods that he is to transfer.

Note the implications that flow from calling this transaction a sale. Creditors of the purchaser can seize the goods. The risk of loss is on the purchaser. The seller cannot recover the goods (to make up for the buyer’s failure to pay him) or sell them to a third party.

Fungible Goods

Fungible goods (goods that are identical, like grain in a silo) present an especially troublesome problem. In many instances the goods of several owners are mingled, and the identical items are not intended to be returned. For example, the operator of a grain elevator agrees to return an equal quantity of like-quality grain but not the actual kernels deposited there. Following the rule in Carpenter’s cow case, this might seem to be a sale, but it is not. Under the UCC, Section 2-207, the depositors of fungible goods are “tenants in common” of the goods; in other words, the goods are owned by all. This distinction between a sale and a bailment is important. When there is a loss through natural causes—for example, if the grain elevator burns—the depositors must share the loss on a pro rata basis (meaning that no single depositor is entitled to take all his grain out; if 20 percent of the grain was destroyed, then each depositor can take out no more than 80 percent of what he deposited).

Elements of a Bailment

As noted, bailment is defined as “the rightful possession of goods by one who is not the owner.” For the most part, this definition is clear (and note that it does not dictate that a bailment be created by contract). Bailment law applies to the delivery of goods—that is, to the delivery personal property. Personal property is usually defined as anything that can be owned other than real estate. As we have just seen in comparing bailments to sales, the definition implies a duty to return the identical goods when the bailment ends.

But one word in the definition is both critical and troublesome: possession. Possession requires both a physical and a mental element. We examine these in turn.

Possession: Physical Control

In most cases, physical control is proven easily enough. A car delivered to a parking garage is obviously within the physical control of the garage. But in some instances, physical control is difficult to conceptualize. For example, you can rent a safe-deposit box in a bank to store valuable papers, stock certificates, jewelry, and the like. The box is usually housed in the bank’s vault. To gain access, you sign a register and insert your key after a bank employee inserts the bank’s key. You may then inspect, add to, or remove contents of the box in the privacy of a small room maintained in the vault for the purpose. Because the bank cannot gain access to the box without your key and does not know what is in the box, it might be said to have no physical control. Nevertheless, the rental of a safe-deposit box is a bailment. In so holding, a New York court pointed out that if the bank was not in possession of the box renter’s property “it is difficult to know who was. Certainly [the renter] was not, because she could not obtain access to the property without the consent and active participation of the defendant. She could not go into her safe unless the defendant used its key first, and then allowed her to open the box with her own key; thus absolutely controlling [her] access to that which she had deposited within the safe. The vault was the [company’s] and was in its custody, and its contents were under the same conditions.”Lockwood v. Manhattan Storage & Warehouse Co., 50 N.Y.S. 974 (N.Y. 1898). Statutes in some states, however, provide that the relationship is not a bailment but that of a landlord and tenant, and many of these statutes limit the bank’s liability for losses.

Possession: Intent to Possess

In addition to physical control, the bailee must have had an intent to possess the goods; that is, to exercise control over them. This mental condition is difficult to prove; it almost always turns on the specific circumstances and, as a fact question, is left to the jury to determine. To illustrate the difficulty, suppose that one crisp fall day, Mimi goes to Sally Jane’s Boutique to try on a jacket. The sales clerk hands Mimi a jacket and watches while Mimi takes off her coat and places it on a nearby table. A few minutes later, when Mimi is finished inspecting herself in the mirror, she goes to retrieve her coat, only to discover it is missing. Who is responsible for the loss? The answer depends on whether the store is a bailee. In some sense the boutique had physical control, but did it intend to exercise that control? In a leading case, the court held that it did, even though no one said anything about guarding the coat, because a store invites its patrons to come in. Implicit in the act of trying on a garment is the removal of the garment being worn. When the customer places it in a logical place, with the knowledge of and without objection from the salesperson, the store must exercise some care in its safekeeping.Bunnell v. Stern, 25 N.E. 910 (N.Y. 1890).

Now suppose that when Mimi walked in, the salesperson told her to look around, to try on some clothes, and to put her coat on the table. When the salesperson was finished with her present customer, she said, she would be glad to help Mimi. So Mimi tried on a jacket and minutes later discovered her coat gone. Is this a bailment? Many courts, including the New York courts, would say no. The difference? The salesperson was helping another customer. Therefore, Mimi had a better opportunity to watch over her own coat and knew that the salesperson would not be looking out for it. This is a subtle distinction, but it has been sufficient in many cases to change the ruling.Wamser v. Browning, King & Co., 79 N.E. 861 (N.Y. 1907).

Questions of intent and control frequently arise in parking lot cases. As someone once said, “The key to the problem is the key itself.” The key is symbolic of possession and intent to possess. If you give the attendant your key, you are a bailorAn owner of property who delivers it to another to hold in bailment. and he (or the company he works for) is the bailee. If you do not give him the key, no bailment arises. Many parking lot cases do not fall neatly within this rule, however. Especially common are cases involving self-service airport parking lots. The customer drives through a gate, takes a ticket dispensed by a machine, parks his car, locks it, and takes his key. When he leaves, he retrieves the car himself and pays at an exit gate. As a general rule, no bailment is created under these circumstances. The lot operator does not accept the vehicle nor intend to watch over it as bailee. In effect, the operator is simply renting out space.Wall v. Airport Parking Co. of Chicago, 244 N.E.2d 190 (Ill. 1969). But a slight change of facts can alter this legal conclusion. Suppose, for instance, that the lot had an attendant at the single point of entrance and exit, that the attendant jotted down the license number on the ticket, one portion of which he retained, and that the car owner must surrender the ticket when leaving or prove that he owns the car. These facts have been held to add up to an intention to exercise custody and control over the cars in the lot, and hence to have created a bailment.Continental Insurance Co. v. Meyers Bros. Operations, Inc., 288 N.Y.S.2d 756 (Civ. Ct. N.Y. 1968).

For a bailment to exist, the bailee must know or have reason to know that the property exists. When property is hidden within the main object entrusted to the bailee, lack of notice can defeat the bailment in the hidden property. For instance, a parking lot is not responsible for the disappearance of valuable golf clubs stored in the trunk of a car, nor is a dance hall cloak room responsible for the disappearance of a fur wrap inside a coat, if they did not know of their existence.Samples v. Geary, 292 S.W. 1066 (Mo. App. 1927). This result is usually justified by observing that when a person is unaware that goods exist or does not know their value, it is inequitable to hold him responsible for their loss since he cannot take steps to prevent it. This rule has been criticized: trunks are meant to hold things, and if the car was within the garage’s control, surely its contents were too. Some courts soften the impact of the rule by holding that a bailee is responsible for goods that he might reasonably expect to be present, like gloves in a coat checked at a restaurant or ordinary baggage in a car checked at a hotel.

Key Takeaway

A bailment arises when one person (a bailee) rightfully holds property belonging to another (a bailor). The law of bailments addresses the critical links in the movement of goods from the manufacturer to the end user in a consumer society: to the storage and transportation of goods. Bailments only apply to personal property; a bailment requires that the bailor deliver physical control of the goods to the bailee, who has an intention to possess the goods and a duty to return them.

Exercises

- Dennis takes his Mercedes to have the GPS system repaired. In the trunk of his car is a briefcase containing $5,000 in cash. Is the cash bailed goods?

- Marilyn wraps up ten family-heirloom crystal goblets, packages them carefully in a cardboard box, and drops the box off at the local UPS store. Are the goblets bailed goods?

- Bob agrees to help his friend Roger build a deck at Roger’s house. Bob leaves some of his tools—without Bob’s noticing—around the corner of the garage at the foot of a rhododendron bush. The tools are partly hidden. Are they bailed goods?

12.2 Liability of the Parties to a Bailment

Learning Objectives

- Understand how the bailee’s liability arises and operates.

- Recognize the cases in which the bailee can disclaim liability, and what limits are put on such disclaimers.

- Understand what duty and liability the bailor has.

- Know other rights and duties that arise in a bailment.

- Understand the extent to which innkeepers—hotel and motels—are liable for their guests’ property.

Liability of the Bailee

Duty of Care

The basic rule is that the bailee is expected to return to its owner the bailed goods when the bailee’s time for possession of them is over, and he is presumed liable if the goods are not returned. But that a bailee has accepted delivery of goods does not mean that he is responsible for their safekeeping no matter what. The law of bailments does not apply a standard of absolute liability: the bailee is not an insurer of the goods’ safety; her liability depends on the circumstances.

The Ordinary Care Rule

Some courts say that the bailee’s liability is the straightforward standard of “ordinary care under the circumstances.” The question becomes whether the bailee exercised such care. If she did, she is not liable for the loss.

The Benefit-of-the-Bargain Rule

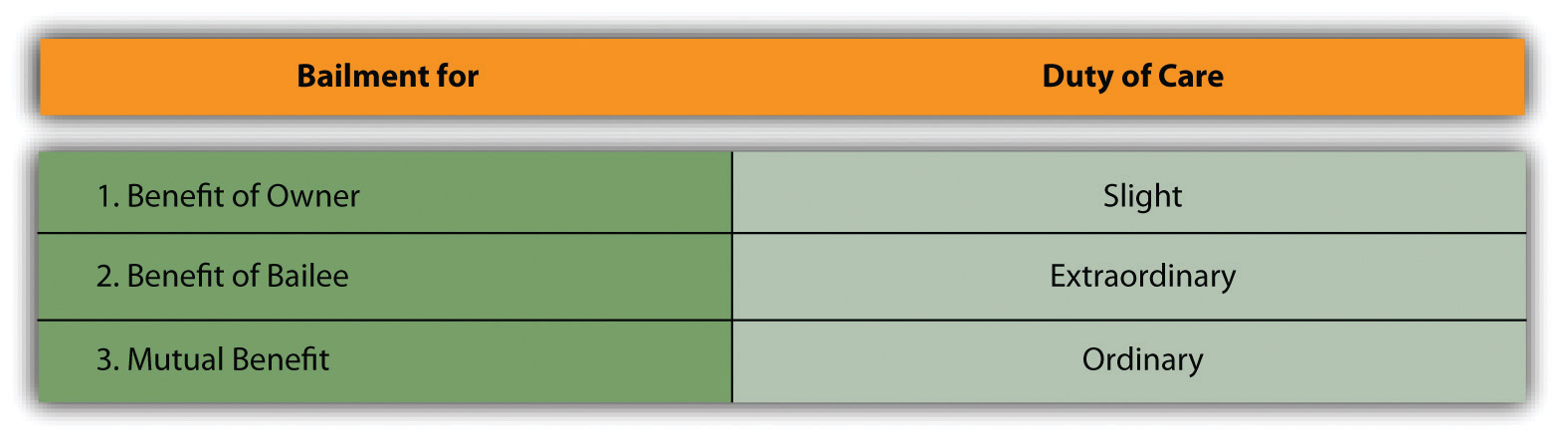

Most courts use a complex (some say annoying) tripartite division of responsibility. If the bailment is for the sole benefit of the owner (the bailor), the bailee is answerable only for gross neglect or fraud: the duty of care is slight. For example, imagine that your car breaks down on a dark night and you beg a passing motorist to tow it to a gas station; or you ask your neighbor if you can store your utility trailer in her garage.

On the other hand, if the goods are entrusted to the bailee for his sole benefit, then he owes the bailor extraordinary care. For example, imagine that your neighbor asks you to let him borrow your car to go to the grocery store downtown because his car is in the shop; or a friend asks if she can borrow your party canopy.

If the bailment is for the mutual benefit of bailee and bailor, then the ordinary negligence standard of care will govern. For example, imagine you park your car in a commercial parking lot, or you take your suit jacket to a dry cleaner (see Figure 12.1 "Duty of Care").

Figure 12.1 Duty of Care

One problem with using the majority approach is the inherent ambiguity in the standards of care. What constitutes “gross” negligence as opposed to “ordinary” negligence? The degree-of-care approach is further complicated by the tendency of the courts to take into account the value of the goods; the lesser the value of the goods, the lesser the obligation of the bailee to watch out for them. To some degree, this approach makes sense, because it obviously behooves a person guarding diamonds to take greater precautions against theft than one holding three paperback books. But the value of the goods ought not to be the whole story: some goods obviously have great value to the owner, regardless of any lack of intrinsic value.

Another problem in using the majority approach to the standard of care is determining whether or not a benefit has been conferred on the bailee when the bailor did not expressly agree to pay compensation. For example, a bank gives its customers free access to safe-deposit boxes. Is the bank a “gratuitous bailee” that owes its bailor only a slight degree of care, or has it made the boxes available as a commercial matter to hold onto its customers? Some courts cling to one theory, some to the other, suggesting the difficulty with the tripartite division of the standard of care. However, in many cases, whatever the formal theory, the courts look to the actual benefits to be derived. Thus when a customer comes to an automobile showroom and leaves her car in the lot while she test-drives the new car, most courts would hold that two bailments for mutual benefit have been created: (1) the bailment to hold the old car in the lot, with the customer as the bailor; and (2) the bailment to try out the new car, with the customer as the bailee.

Burden of Proof

In a bailment case, the plaintiff bailor has the burden of proving that a loss was caused by the defendant bailee’s failure to exercise due care. However, the bailor establishes a prima facie (“at first sight”—on first appearance, but subject to further investigation) case by showing that he delivered the goods into the bailee’s hands and that the bailee did not return them or returned them damaged. At that point, a presumption of negligence arises, and to avoid liability the defendant must rebut that presumption by showing affirmatively that he was not negligent. The reason for this rule is that the bailee usually has a much better opportunity to explain why the goods were not returned or were returned damaged. To put this burden on the bailor might make it impossible for him to win a meritorious case.

Liability of the Bailor

As might be expected, most bailment cases involve the legal liability of bailees. However, a body of law on the liability of bailors has emerged.

Negligence of Bailor

A bailor may be held liable for negligence. If the bailor receives a benefit from the bailment, then he has a duty to inform the bailee of known defects and to make a reasonable inspection for other defects. Suppose the Tranquil Chemical Manufacturing Company produces an insecticide that it wants the Plattsville Chemical Storage Company to keep in tanks until it is sold. One of the batches is defectively acidic and oozes out of the tanks. This acidity could have been discovered through a routine inspection, but Tranquil neglects to inspect the batch. The tanks leak and the chemical builds up on the floor until it explodes. Since Tranquil, the bailor, received a benefit from the storage, it had a duty to warn Plattsville, and its failure to do so makes it liable for all damages caused by the explosion.

If the bailor does not receive any benefit, however, then his only duty is to inform the bailee of known defects. Your neighbor asks to borrow your car. You have a duty to tell her that the brakes are weak, but you do not need to inspect the car beforehand for unknown defects.

Other Types of Liability

The theory of products liability discussed in Chapter 11 "Products Liability" extends to bailors. Both warranty and strict liability theories apply. The rationale for extending liability in the absence of sale is that in modern commerce, damage can be done equally by sellers or lessors of equipment. A rented car can inflict substantial injury no less than a purchased one.

In several states, when an automobile owner (bailor) lends a vehicle to a friend (bailee) who causes an accident, the owner is liable to third persons injured in the accident. This liability is discussed in (Reference mayer_1.0-ch38 not found in Book), which covers agency law.

Disclaimers of Liability

Bailee’s Disclaimer

Bailees frequently attempt to disclaim their liability for loss or damage. But courts often refuse to honor the disclaimers, usually looking to one of two justifications for invalidating them.

Lack of Notice

The disclaimer must be brought to the attention of the bailor and must be unambiguous. Thus posted notices and receipts disclaiming or limiting liability must set forth clearly and legibly the legal effects intended. Most American courts follow the rule that the defendant bailee must show that the bailor in fact knew about the disclaimer. Language printed on the back side of a receipt will not do.

Public Policy Exception

Even if the bailor reads the disclaimer, some courts will nevertheless hold the bailee liable on public policy grounds, especially when the bailee is a “business bailee,” such as a warehouse or carrier. Indeed, to the extent that a business bailee attempts to totally disclaim liability, he will probably fail in every American jurisdiction. But the Restatement (Second) of Contracts, Section 195(2)(b), does not go quite this far for most nonbusiness bailees. They may disclaim liability as long as the disclaimer is read and does not relieve the bailee from wanton carelessness.

Bailor’s Disclaimer

Bailors most frequently attempt to disclaim liability in rental situations. For example, in Zimmer v. Mitchell and Ness, the plaintiff went to the defendant’s rental shop at the Camelback ski area to rent skis, boots, and poles.Zimmer v. Mitchell and Ness, 385 A.2d 437 (Penn. 1978). He signed a rental agreement before accepting the ski equipment. He was a lessee and a bailee. Later, while descending the beginners’ slope, he fell. The bindings on his skis did not release, thereby causing him to sustain numerous injuries. The plaintiff sued the defendant and Camelback Ski Corporation, alleging negligence, violation of Section 402A of the Restatement (Second) of Torts, and breach of warranty. The defendant filed an answer and claimed that the plaintiff signed a rental agreement that fully released the defendant from liability. In his reply, the plaintiff admitted signing the agreement but generally denied that it released the defendant from liability. The defendant won on summary judgment.

On appeal, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court held for the defendant and set out the law: “The test for determining the validity of exculpatory clauses, admittedly not favored in the law, is set out in [Citation]. The contract must not contravene any policy of the law. It must be a contract between individuals relating to their private affairs. Each party must be a free bargaining agent, not simply one drawn into an adhesion contract, with no recourse but to reject the entire transaction.…We must construe the agreement strictly and against the party asserting it [and], the agreement must spell out the intent of the parties with the utmost particularity.” The court here was satisfied with the disclaimer.

Other Rights and Duties

Compensation

If the bailor hires the bailee to perform services for the bailed property, then the bailee is entitled to compensation. Remember, however, that not every bailment is necessarily for compensation. The difficult question is whether the bailee is entitled to compensation when nothing explicit has been said about incidental expenses he has incurred to care for the bailed property—as, for example, if he were to repair a piece of machinery to keep it running. No firm rule can be given. Perhaps the best generalization that can be made is that, in the absence of an express agreement, ordinary repairs fall to the bailee to pay, but extraordinary repairs are the bailor’s responsibility. An express agreement between the parties detailing the responsibilities would solve the problem, of course.

Bailee’s Lien

Lien is from the French, originally meaning “line,” “string,” or “tie.” In law a lienAn encumbrance upon property to secure payment. is the hold that someone has over the property of another. It is akin, in effect, to a security interest. A common type is the mechanic’s lienA claim allowed to one who furnishes labor, services, or materials to improve property. (“mechanic” here means one who works with his hands). For example, a carpenter builds a room on your house and you fail to pay him; he can secure a lien on your house, meaning that he has a property interest in the house and can start foreclosure proceedings if you still fail to pay. Similarly, a bailee is said to have a lien on the bailed property in his possession and need not redeliver it to the bailor until he has been paid. Try to take your car out of a parking lot without paying and see what happens. The attendant’s refusal to give you the car is entirely lawful under a common-law rule now more than a century and a half old. As the rule is usually stated, the common law confers the lien on the bailee if he has added value to the property through his labor, skill, or materials. But that statement of the rule is somewhat deceptive, since the person who has simply housed the goods is entitled to a lien, as is a person who has altered or repaired the goods without measurably adding value to them. Perhaps a better way of stating the rule is this: a lien is created when the bailee performs some special benefit to the goods (e.g., preserving them or repairing them).

Many states have enacted statutes governing various types of liens. In many instances, these have broadened the bailee’s common-law rights. This book discusses two types of liens in great detail: the liens of warehousemen and those of common carriers. Recall that a lease creates a type of bailment: the lessor is the bailor and the lessee is the bailee. This book references the UCC’s take on leasing in its discussion of the sale of goods.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 2A.

Rights When Goods Are Taken or Damaged by a Third Party

The general rule is that the bailee can recover damages in full if the bailed property is damaged or taken by a third party, but he must account in turn to the bailor. A delivery service is carrying parcels—bailed goods entrusted to the trucker for delivery—when the truck is struck from behind and blows up. The carrier may sue the third person who caused the accident and recover for the total loss, including the value of the packages. The bailor may also recover for damages to the parcels, but not if the bailee has already recovered a judgment. Suppose the bailee has sued and lost. Does the bailor have a right to sue independently on the same grounds? Ordinarily, the principle of res judicata would prevent a second suit, but if the bailor did not know of and cooperate in the bailee’s suit, he probably has the right to proceed on his own suit.

Innkeepers’ Liability

The liability of an innkeeper—a type of bailor—is thought to have derived from the warlike conditions that prevailed in medieval England, where brigands and bandits roamed the countryside and the innkeeper himself might not have been above stealing from his guests. The innkeeper’s liability extended not merely to loss of goods through negligence. His was an insurer’s liability, extending to any loss, no matter how occasioned, and even to losses that occurred in the guest’s room, a place where the guest had the primary right of possession. The only exception was for losses due to the guest’s own negligence.

Most states have enacted statutes providing exceptions to this extraordinarily broad common-law duty. Typically, the statutes exempt the hotel keeper from insurer’s liability if the hotelier furnishes a safe in which the guests can leave their jewels, money, and other valuables and if a notice is posted a notice advising the guests of the safe’s availability. The hotelier might face liability for valuables lost or stolen from the safe but not from the rooms.

Key Takeaway

If the bailee fails to redeliver the goods to the bailor, a presumption of negligence arises, but the bailee can rebut the presumption by showing that she exercised appropriate care. What is “appropriate care” depends on the test used in the jurisdiction: some courts use the “ordinary care under the circumstances,” and some determine how much care the bailee should have exercised based on the extent to which she was benefited from the transaction compared to the bailor. The bailor can be liable too for negligently delivering goods likely to cause damage to the bailee. In either case reasonable disclaimers of liability are allowed. If the bailed goods need repair while in the bailee’s possession, the usual rule is that ordinary repairs are the bailee’s responsibility, extraordinary ones the bailor’s. Bailees are entitled to liens to enforce payment owing to them. In common law, innkeepers were insurers of their guests’ property, but hotels and motels today are governed mostly by statute: they are to provide a safe for their guests’ valuables and are not liable for losses from the room.

Exercises

- What is the “ordinary care under the circumstances” test for a bailee’s liability when the bailed goods are not returned?

- What is the tripartite test?

- What liability does a bailor have for delivering defective goods to a bailee?

- Under what circumstances are disclaimers of liability by the bailee or bailor acceptable?

- Jason takes his Ford Mustang to a repair shop but fails to pay for the repairs. On what theory can the shop keep and eventually sell the car to secure payment?

12.3 The Storage and Shipping of Goods

Learning Objectives

- Understand a warehouser’s liability for losing goods, what types of losses a warehouser is liable for, and what rights the warehouser has concerning the goods.

- Know the duties, liabilities, and exceptions to liability a carrier of freight has, and what rights the carrier has.

- Understand the liability that is imposed on entities whose business it is to carry passengers.

Storage of Goods

Warehousing has been called the “second oldest profession,” stemming from the biblical story of Joseph, who stored grain during the seven good years against the famine of the seven bad years. Whatever its origins, warehousing is today a big business, taking in billions of dollars to stockpile foods and other goods. As noted previously, the source of law governing warehousing is Article 7 of the UCC, but noncode law also can apply. Section 7-103 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) specifically provides that any federal statute or treaty and any state regulation or tariff supersedes the provisions of Article 7. A federal example is the United States Warehouse Act, which governs receipts for stored agricultural products. Here we take up, after some definitions, the warehouser’s liabilities and rights. A warehouser is a special type of bailee.

Definitions

A warehouserOne whose business it is to store goods. is defined in UCC, Section 7-102(h), as “a person engaged in the business of storing goods for hire,” and under Section 1-201(45) a warehouse receiptA written document for items warehoused, serving as evidence of title to the stored goods. is any receipt issued by a warehouser. The warehouse receipt is an important document because it can be used to transfer title to the goods, even while they remain in storage: it is worth money. No form is prescribed for the warehouse receipt, but unless it lists in its terms the following nine items, the warehouser is liable to anyone who is injured by the omission of any of them:

- Location of the warehouse

- Date receipt was issued

- Consecutive number of the receipt

- Statement whether the goods will be delivered to bearer, to a specified person, or “to a specified person or his order”

- The rate of storage and handling charges

- Description of the goods or the packages containing them

- Signature of the warehouser, which his or her authorized agent may make

- The warehouser’s ownership of the goods, if he or she has a sole or part ownership in them

- The amount (if known, otherwise the fact) of advances made and liabilities incurred for which the warehouser claims a lien or security interest

General Duty of Care

The warehouser’s general duty of care is embodied in the tort standard for measuring negligence: he is liable for any losses or injury to the goods caused by his failure to exercise “such care in regard to them as a reasonably careful man would exercise under like circumstances.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 7-204(1). However, subsection 4 declares that this section does not repeal or dilute any other state statute that imposes a higher responsibility on a warehouser. Nor does the section invalidate contractual limitations otherwise permissible under Article 7. The warehouser’s duty of care under this section is considerably weaker than the carrier’s duty. Determining when a warehouser becomes a carrier, if the warehouser is to act as shipper, can become an important issue.

Limitation of Liability

The warehouser may limit the amount of damages she will pay by so stating in the warehouse receipt, but she must strictly observe that section’s requirements, under which the limitation must be stated “per article or item, or value per unit of weight.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 7-204(2). Moreover, the warehouser cannot force the bailor to accept this limitation: the bailor may demand in writing increased liability, in which event the warehouser may charge more for the storage. If the warehouser converts the goods to her own UCC, the limitation of liability does not apply.

Specific Types of Liability and Duties

Several problems recur in warehousing, and the law addresses them.

Nonreceipt or Misdescription

Under UCC Section 7-203, a warehouser is responsible for goods listed in a warehouse receipt that were not in fact delivered to the warehouse (or were misdescribed) and must pay damages to a good-faith purchaser of or party to a document of title. To avoid this liability, the issuer must conspicuously note on the document that he does not know whether the goods were delivered or are correctly described. One simple way is to mark on the receipt that “contents, condition, and quality are unknown.”

Delivery to the Wrong Party

The bailee is obligated to deliver the goods to any person with documents that entitle him to possession, as long as the claimant pays any outstanding liens and surrenders the document so that it can be marked “cancelled” (or can be partially cancelled in the case of partial delivery). The bailee can avoid liability for no delivery by showing that he delivered the goods to someone with a claim to possession superior to that of the claimant, that the goods were lost or destroyed through no fault of the bailee, or that certain other lawful excuses apply.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 7-403(1). Suppose a thief deposits goods he has stolen with a warehouse. Discovering the theft, the warehouser turns the goods over to the rightful owner. A day later the thief arrives with a receipt and demands delivery. Because the rightful owner had the superior claim, the warehouser is not liable in damages to the thief.

Now suppose you are moving and have placed your goods with a local storage company. A few weeks later, you accidentally drop your wallet, which contains the receipt for the goods and all your identification. A thief picks up the wallet and immediately heads for the warehouse, pretending to be you. Having no suspicion that anything is amiss—it’s a large place and no one can be expected to remember what you look like—the warehouse releases the goods to the thief. This time you are probably out of luck. Section 7-404 says that “a bailee who in good faith including observance of reasonable commercial standards has received goods and delivered…them according to the terms of the document of title…is not liable.” This rule is true even though the person to whom he made delivery had no authority to receive them, as in the case of the thief. However, if the warehouser had a suspicion and failed to take precautions, then he might be liable to the true owner.

Duty to Keep Goods Separate

Except for fungible goods, like grain, the warehouse must keep separate goods covered by each warehouse receipt. The purpose of this rule, which may be negated by explicit language in the receipt, is to permit the bailor to identify and take delivery of his goods at any time.

Rights of the Warehouser

The warehouser has certain rights concerning the bailed goods.

Termination

A warehouser is not obligated to store goods indefinitely. Many warehouse receipts will specify the period of storage. At the termination of the period, the warehouser may notify the bailor to pay and to recover her goods. If no period is fixed in the receipt or other document of title, the warehouser may give notice to pay and remove within no less than thirty days. The bailor’s failure to pay and remove permits the warehouser to sell the goods for her fee. Suppose the goods begin to deteriorate. Sections 7-207(2) and 7-207(3) of the UCC permit the warehouser to sell the goods early if necessary to recover the full amount of her lien or if the goods present a hazard. But if the rightful owner demands delivery before such a sale, the warehouser is obligated to do so.

Liens

Section 7-209(1) of the UCC provides that a warehouser has a lien on goods covered by a warehouse receipt to recover the following charges and expenses: charges for storage or transportation, insurance, labor, and expenses necessary to preserve the goods. The lien is not discharged if the bailor transfers his property interest in the goods by negotiating a warehouse receipt to a purchaser in good faith, although the warehouser is limited then to an amount or a rate fixed in the receipt or to a reasonable amount or rate if none was stated. The lien attaches automatically and need not be spelled out in the warehouse receipt.

The warehouser may enforce the lien by selling the goods at a public or private sale, as long as she does so in a commercially reasonable manner, as defined in Section 7-210. All parties known to be claiming an interest in the goods must be notified of the sale and told the amount due, the nature of the sale, and its time and place. Any person who in good faith purchases the goods takes them free of any claim by the bailor, even if the warehouser failed to comply with the requirements of Section 7-210. However, her failure to comply subjects her to damages, and if she has willfully violated the provisions of this section she is liable to the bailor for conversion.

Shipment of Goods

Introduction and Terminology

The shipment of goods throughout the United States and abroad is a very big business, and many specialized companies have been established to undertake it, including railways, air cargo operations, trucking companies, and ocean carriers. Article 7 of the UCC applies to carriage of goods as it does to warehousing, but federal law is more important. The Federal Bill of Lading Act (FBLA) covers bills of lading issued by common carriers for transportation of goods in interstate or foreign commerce (i.e., from one state to another; in federal territory; or to foreign countries). The Carmack Amendment was enacted in 1906 as an amendment to the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, and it is now part of the Interstate Commerce Commission Termination Act of 1995; it covers liability of interstate carriers for loss, destruction, and damage to goods. The shipperOne who engages the services of a carrier. is the entity hiring the one who transports the goods: if you send your sister crystal goblets for her birthday, you are the shipper.

Two terms are particularly important in discussing shipment of goods. One is common carrier; the common carrierA carrier that holds itself open to any member of the public for a fee. is “one who undertakes for hire or reward to transport the goods of such as chooses to employ him, from place to place.”Ace High Dresses v. J. C. Trucking Co., 191 A. 536 (Conn. 1937). This definition contains three elements: (1) the carrier must hold itself out for all in common for hire—the business is not restricted to particular customers but is open to all who apply for its services; (2) it must charge for his services—it is for hire; (3) the service in question must be carriage. Included within this tripartite definition are numerous types of carriers: household moving companies, taxicabs, towing companies, and even oil and gas pipelines. Note that to be a common carrier it is not necessary to be in the business of carrying every type of good to every possible point; common carriers may limit the types of goods or the places to which they will transport them.

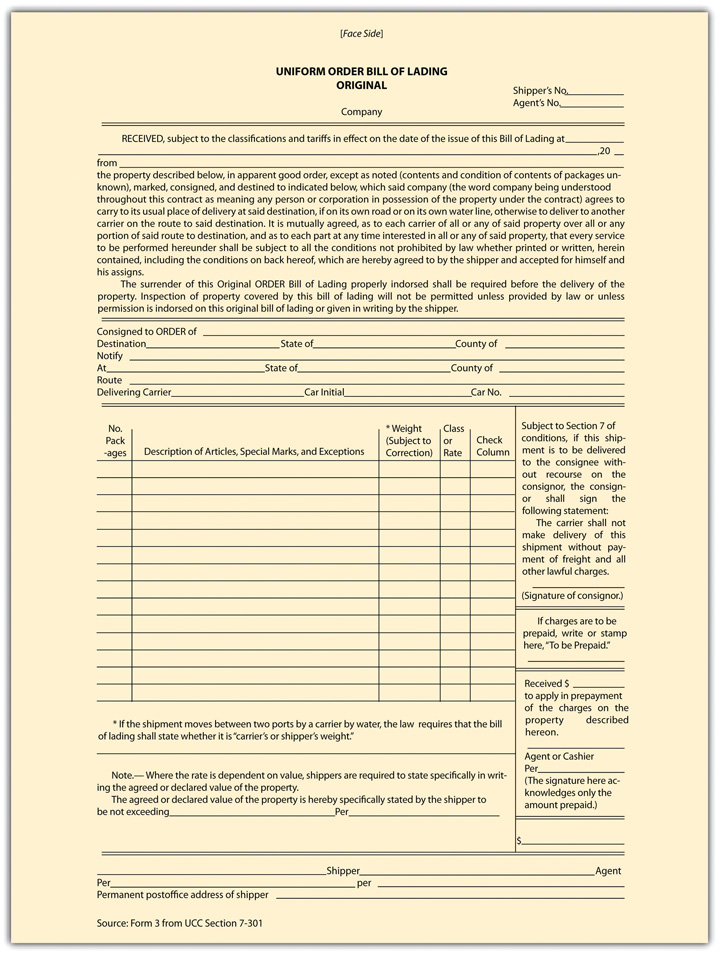

A bill of ladingA document of title acknowledging receipt of goods by a carrier. is any document that evidences “the receipt of goods for shipment issued by a person engaged in the business of transporting or forwarding goods.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 1-206(6). This is a comprehensive definition and includes documents used by contract carriers—that is, carriers who are not common carriers. An example of a bill of lading is depicted in Figure 12.2 "A Bill of Lading Form".

Figure 12.2 A Bill of Lading Form

Duties and Liabilities

The transportation of goods has been an important part of all evolved economic systems for a long time, and certainly it is critical to the development and operation of any capitalistic system. The law regarding it is well developed.

Absolute Liability

Damage, destruction, and loss are major hazards of transportation for which the carrier will be liable. Who will assert the claim against the carrier depends on who bears the risk of loss. The rules governing risk of loss (examined in Chapter 9 "Title and Risk of Loss") determine whether the buyer or seller will be the plaintiff. But whoever is the plaintiff, the common carrier defendant faces absolute liability. With five exceptions explored two paragraphs on, the common carrier is an insurer of goods, and regardless of the cause of damage or loss—that is, whether or not the carrier was negligent—it must make the owner whole. This ancient common-law rule is codified in state law, in the federal Carmack Amendment, and in the UCC, Section 7-309(1), all of which hold the common carrier to absolute liability to the extent that the common law of the state had previously done so.

Absolute liability was imposed in the early cases because the judges believed such a rule was necessary to prevent carriers from conspiring with thieves. Since it is difficult for the owner, who was not on the scene, to prove exactly what happened, the judges reasoned that putting the burden of loss on the carrier would prompt him to take extraordinary precautions against loss (and would certainly preclude him from colluding with thieves). Note that the rules in this section govern only common carriers; contract carriers that do not hold themselves out for transport for hire are liable as ordinary bailees.

Exceptions to Absolute Liability

In general, the burden or proof rests on the carrier in favor of the shipper. The shipper (or consignee of the shipper) can make out a prima facie case by showing that it delivered the goods to the carrier in good condition and that the goods either did not arrive or arrived damaged in a specified amount. Thereafter the carrier has the burden of proving that it was not negligent and that the loss or damage was caused by one of the five following recognized exceptions to the rule of absolute liability.

Act of God

No one has ever succeeded in defining precisely what constitutes an act of God, but the courts seem generally agreed that it encompasses acts that are of sudden and extraordinary natural, as opposed to human, origin. Examples of acts of God are earthquakes, hurricanes, and fires caused by lightning against which the carrier could not have protected itself. Rapid River Carriers contracts to transport a refrigerated cargo of beef down the Mississippi River on the SS Rapid. When the ship is en route, it is hit by a tornado and sinks. This is an act of God. But a contributing act of negligence by a carrier overcomes the act of God exception. If it could be shown that the captain was negligent to set sail when the weather warned of imminent tornados, the carrier might be liable.

Act of Public Enemy

This is a narrow exception that applies only to acts committed by pirates at high sea or by the armed forces of enemies of the state to which the carrier owes allegiance. American ships at sea that are sunk during wartime by enemy torpedoes would not be liable for losses to the owners of cargo. Moreover, public enemies do not include lawless mobs or criminals listed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list, even if federal troops are required, as in the Pullman Strike of 1894, to put down the violence. After the Pullman Strike, carriers were held liable for property destroyed by violent strikers.

Act of Public Authority

When a public authority—a sheriff or federal marshal, for example—through lawful process seizes goods in the carrier’s possession, the carrier is excused from liability. Imagine that federal agents board the SS Rapid in New Orleans and, as she is about to sail, show the captain a search warrant and seize several boxes of cargo marked “beef” that turn out to hold cocaine. The owner or consignee of this illegal cargo will not prevail in a suit against the carrier to recover damages. Likewise, if the rightful owner of the goods obtains a lawful court order permitting him to attach them, the carrier is obligated to permit the goods to be taken. It is not the carrier’s responsibility to contest a judicial writ or to face the consequences of resisting a court order. The courts generally agree that the carrier must notify the owner whenever goods are seized.

Act of Shipper

When goods are lost or damaged because of the shipper’s negligence, the shipper is liable, not the carrier. The usual situation under this exception arises from defective packing. The shipper who packs the goods defectively is responsible for breakage unless the defect is apparent and the carrier accepts the goods anyway. For example, if you ship your sister crystal goblets packed loosely in the box, they will inevitably be broken when driven in trucks along the highways. The trucker who knowingly accepts boxes in this condition is liable for the damage. Likewise, the carrier’s negligence will overcome the exception and make him absolutely liable. A paper supplier ships several bales of fine stationery in thin cardboard boxes susceptible to moisture. Knowing their content, SS Rapid accepts the bales and exposes them to the elements on the upper deck. A rainstorm curdles the stationery. The carrier is liable.

Inherent Nature of the Goods

The fifth exception to the rule of absolute liability is rooted in the nature of the goods themselves. If they are inherently subject to deterioration or their inherent characteristics are such that they might be destroyed, then the loss must lie on the owner. Common examples are chemicals that can explode spontaneously and perishable fruits and vegetables. Of course, the carrier is responsible for seeing that foodstuffs are properly stored and cared for, but if they deteriorate naturally and not through the carrier’s negligence, he is not liable.

Which Carrier Is Liable?

The transportation system is complex, and few goods travel from portal to portal under the care of one carrier only. In the nineteenth century, the shipper whose goods were lost had a difficult time recovering their value. Initial carriers blamed the loss on subsequent carriers, and even if the shipper could determine which carrier actually had possession of the goods when the damage or loss occurred, diverse state laws made proof burdensome. The Carmack Amendment ended the considerable confusion by placing the burden on the initial carrier; connecting carriers are deemed agents of the initial carrier. So the plaintiff, whether seller or buyer, need sue only the initial carrier, no matter where the loss occurred. Likewise, Section 7-302 of the UCC fastens liability on an initial carrier for damages or loss caused by connecting carriers.

When Does Carrier Liability Begin and End?

When a carrier’s liability begins and ends is an important issue because the same company can act both to store the goods and to carry them. The carrier’s liability is more stringent than the warehouser’s. So the question is, when does a warehouser become a carrier and vice versa?

The basic test for the beginning of carrier liability is whether the shipper must take further action or give further instructions to the carrier before its duty to transport arises. Suppose that Cotton Picking Associates delivers fifty bales of cotton to Rapid River Carriers for transport on the SS Rapid. The SS Rapid is not due back to port for two more days, so Rapid River Carrier stores the cotton in its warehouse, and on the following day the warehouse is struck by lightning and burns to the ground. Is Rapid River Carriers liable in its capacity as a carrier or warehouse? Since nothing was left for the owner to do, and Rapid River was storing the cotton for its own convenience awaiting the ship’s arrival, it was acting as a carrier and is liable for the loss. Now suppose that when Cotton Picking Associates delivered the fifty bales it said that another fifty bales would be coming in a week and the entire lot was to be shipped together. Rapid River stores the first fifty bales and lightning strikes. Since more remained for Cotton Picking to do before Rapid River was obligated to ship, the carrier was acting in its warehousing capacity and is not liable.

The carrier’s absolute liability ends when it has delivered the goods to the consignee’s residence or place of business, unless the agreement states otherwise (as it often does). By custom, certain carriers—notably rail carriers and carriers by water—are not required to deliver the goods to the consignee (since rail lines and oceans do not take the carrier to the consignee’s door). Instead, consignees must take delivery at the dock or some other place mutually agreed on or established by custom.

When the carrier must make personal delivery to the consignee, carrier liability continues until the carrier has made reasonable efforts to deliver. An express trucking company cannot call on a corporate customer on Sunday or late at night, for instance. If reasonable efforts to deliver fail, it may store the goods in its own warehouse, in which case its liability reverts to that of a warehouser.

If personal delivery is not required (e.g., as in shipment by rail), the states use different approaches for determining when the carrier’s liability terminates. The most popular intrastate approach provides that the carrier continues to be absolutely responsible for the goods until the consignee has been notified of their arrival and has had a reasonable opportunity to take possession of them.

Interstate shipments are governed by the Carmack Amendment, which generally provides that liability will be determined by language in the bill of lading. The typical bill of lading (or “BOL” and “B/L”) provides that if the consignee does not take the goods within a stated period of time after receiving notice of their arrival, the carrier will be liable as warehouser only.

Disclaimers

The apparently draconian liability of the carrier—as an insurer of the goods—is in practice easily minimized. Under neither federal nor state law may the carrier disclaim its absolute liability, but at least as to commercial transactions it may limit the damages payable under certain circumstances. Both the Carmack Amendment and Section 7-309 of the UCC permit the carrier to set alternate tariffs, one costing the shipper more and paying full value, the other costing less and limited to a dollar per pound or some other rate less than full value. The shipper must have a choice; the carrier may not impose a lesser tariff unilaterally on the shipper, and the loss must not be occasioned by the carrier’s own negligence.

Specific Types of Liability

The rules just discussed relate to the general liability of the carrier for damages to the goods. There are two specific types of liability worth noting.

Nonreceipt or Misdescription

Under the UCC, Section 7-301(1), the owner of the goods (e.g., a consignee) described in a bill of lading may recover damages from the issuer of the bill (the carrier) if the issuer did not actually receive the goods from the shipper, if the goods were misdescribed, or if the bill was misdated. The issuer may avoid liability by reciting in the bill of lading that she does not know whether the goods were received or if they conform to the description; the issuer may avoid liability also by marking the goods with such words as “contents or condition of contents unknown.” Even this qualifying language may be ineffective. For instance, a common carrier may not hide behind language indicating that the description was given by the shipper; the carrier must actually count the packages of goods or ascertain the kind and quantity of bulk freight. Just because the carrier is liable to the consignee for errors in description does not mean that the shipper is free from blame. Section 7-301(5) requires the shipper to indemnify the carrier if the shipper has inaccurately described the goods in any way (including marks, labels, number, kind, quantity, condition, and weight).

Delivery to the Wrong Party

The rule just discussed for warehouser applies to carriers under both state and federal law: carriers are absolutely liable for delivering the goods to the wrong party. In the classic case of Southern Express Co. v. C. L. Ruth & Son, a clever imposter posed as the representative of a reputable firm and tricked the carrier into delivering a diamond ring.Southern Express Co. v. C. L. Ruth & Son, 59 So. 538 (Ala. Ct. App. 1912). The court held the carrier liable, even though the carrier was not negligent and there was no collusion. The UCC contains certain exceptions; under Section 7-303(1), the carrier is immune from liability if the holder, the consignor, or (under certain circumstances) the consignee gives instructions to deliver the goods to someone other than a person named in the bill of lading.

Carrier’s Right to Lien and Enforcement of Lien

Just as the warehouser can have a lien, so too can the carrier. The lien can cover charges for storage, transportation, and preservation of goods. When someone has purchased a negotiable bill of lading, the lien is limited to charges stated in the bill, allowed under applicable tariffs, or, if none are stated, to a reasonable charge. A carrier who voluntarily delivers or unjustifiably refuses to deliver the goods loses its lien. The carrier has rights paralleling those of the warehouser to enforce the lien.

Passengers

In addition to shipping goods, common carriers also transport passengers and their baggage. The carrier owes passengers a high degree of care; in 1880 the Supreme Court described the standard as “the utmost caution characteristic of very careful prudent men.”Pennsylvania Co. v. Roy, 102 US 451 (1880). This duty implies liability for a host of injuries, including mental distress occasioned by insults (“lunatic,” “whore,” “cheap, common scalawag”) and by profane or indecent language. In Werndli v. Greyhound,Werndli v. Greyhound Corp., 365 So.2d 177 (Fla. Ct. App., 1978) Mrs. Werndli deboarded the bus at her destination at 2:30 a.m.; finding the bus station closed, she walked some distance to find a bathroom. While doing so, she became the victim of an assault. The court held Greyhound liable: it should have known the station was closed at 2:30 a.m. and that it was located in a area that became dangerous after hours. The case illustrates the degree to which a carrier is responsible for its passengers’ safety and comfort.

The baggage carrier is liable as an insurer unless the baggage is not in fact delivered to the carrier. A passenger who retains control over his hand luggage by taking it with him to his seat has not delivered the baggage to the carrier, and hence the carrier has no absolute liability for its loss or destruction. The carrier remains liable for negligence, however. When the passenger does deliver his luggage to the carrier, the question often arises whether the property so delivered is “baggage.” If it is not, the carrier does not have an insurer’s liability toward it. Thus a person who transports household goods in a suitcase would not have given the carrier “baggage,” as that term is usually defined (i.e., something transported for the passenger’s personal use or convenience). At most, the carrier would be responsible for the goods as a gratuitous bailee.

Key Takeaway

The storage of goods is a special type of bailment. People who store goods can retrieve them or transfer ownership of them by transferring possession of the warehouse receipt: whoever has rightful possession of the receipt can take the goods, and the warehouser is liable for misdelivery or for mixing up goods. The warehouser has a right to a lien to secure his fee, enforceable by selling the goods in a commercially reasonable way. The shipping of goods is of course an important business. Common carriers (those firms that hire out their trucks, airplanes, ships, or trains to carry cargo) are strictly liable to ensure the proper arrival of the goods to their destination, with five exceptions (act of God, public enemy, public authority, shipper; inherent nature of the goods); the first carrier to receive them is liable—others who subsequently carry are that carrier’s agents. The carrier may also store goods: if it does so for its own convenience it is liable as a carrier; if it does so for the shipper’s convenience, it is liable as a warehouser. As with warehousers, the carrier is liable for misdelivery and is entitled to a lien to enforce payment. Carriers also carry people, and the standard of care they owe to passengers is very high. Carrying passengers’ baggage, the carrier is liable as an insurer—it is strictly liable.

Exercises

- How are warehousers any different from the more generic bailees?

- How do the duties and liabilities of warehousers differ from those of carriers?

- What rights do warehousers and carriers have to ensure their payment?

- May a carrier limit its liability for losses not its fault?

12.4 Negotiation and Transfer of Documents of Title (or Commodity Paper)

Learning Objectives

- Understand how commodity paper operates in the sale of goods.

- Recognize when the transferee of a properly negotiated document of title gets better rights than her transferor had and the exceptions to this principle.

Overview of Negotiability

We have discussed in several places the concept of a document of titleA written description of goods authorizing its holder to have them. (also called commodity paperA loan or cash advance secured by commodities, bills of lading, or warehouse receipts.). That is a written description, identification, or declaration of goods authorizing the holder—usually a bailee—to receive, hold, and dispose of the document and the goods it covers. Examples of documents of title are warehouse receipts, bills of lading, and delivery orders. The document of title, properly negotiated (delivered), gives its holder ownership of the goods it represents. It is much easier to pass around a piece of paper representing the ownership interest in goods than it is to pass around the goods themselves.

It is a basic feature of our legal system that a person cannot transfer more rights to property than he owns. It would follow here that no holder of a document of title has greater rights in the goods than the holder’s transferor—the one from whom she got the document (and thus the goods). But there are certain exceptions to this rule; for example, Chapter 8 "Introduction to Sales and Leases" discusses the power of a merchant in certain circumstances to transfer title to goods, even though the merchant himself did not have title to them. A critically important exception to the general rule arises when certain types of paper are sold. Chapter 14 "Negotiation of Commercial Paper" discusses this rule as it relates to commercial paper such as checks and notes. To conclude this chapter, we discuss the rule as it applies to documents of title, sometimes known as commodity paper.

The Elements and Effect of Negotiation

If a document of title is “negotiable” and is “duly negotiated,” the purchaser can obtain rights greater than those of the storer or shipper. In the following discussion, we refer only to the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), although federal law also distinguishes between negotiable and nonnegotiable documents of title (some of the technical details in the federal law may differ, but these are beyond the scope of this book).

Negotiable Defined

Any document of title, including a warehouse receipt and a bill of lading, is negotiable or becomes negotiable if by its terms the goods are to be delivered “to bearer or to the order of” a named person.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 7-104(1)(a). All other documents of title are nonnegotiable. Suppose a bill of lading says that the goods are consigned to Tom Thumb but that they may not be delivered unless Tom signs a written order that they be delivered. Under Section 7-104(2), that is not a negotiable document of title. A negotiable document of title must bear words such as “Deliver to the bearer” or “deliver to the order of Tom Thumb.” These are the “magic words” that create a negotiable document.

Duly Negotiated

To transfer title effectively through negotiation of the document of title, it must be “duly negotiated.” In general terms, under Section 7-501 of the UCC, a negotiable document of title is duly negotiatedThe transfer of commercial paper to a legitimate transferee, usually by indorsement. when the person named in it indorses (signs it over—literally “on the back of”) and delivers it to a holder who purchases it in good faith and for value, without any notice that someone else might have a claim against the goods, assuming the transaction is in the regular course of business or financing. Note that last part: assuming the transaction is in the regular course of business. If you gave your roommate a negotiable document of title in payment for a car you bought from her, your roommate would have something of value, but it would not have been duly negotiated. Paper made out “to bearer” (bearer paperA negotiable instrument payable to whoever has possession.) is negotiated by delivery alone; no indorsement is needed. A holderOne who has legal possession of a negotiable instrument and who is entitled to payment. is anyone who possesses a document of title that is drawn to his order, indorsed to him, or made out “to bearer.”

Effect

As a general rule, if these requirements are not met, the transferee acquires only those rights that the transferor had and nothing more. And if a nonnegotiable document is sold, the buyer’s rights may be defeated. For example, a creditor of the transferor might be entitled to treat the sale as void.

Under Section 7-502 of the UCC, however, if the document is duly negotiated, then the holder acquires (1) title to the document, (2) title to the goods, (3) certain rights to the goods delivered to the bailee after the document itself was issued, and (4) the right to have the issuer of the document of title hold the goods or deliver the goods free of any defense or claim by the issuer.

To contrast the difference between sale of goods and negotiation of the document of title, consider the plight of Lucy, the owner of presidential campaign pins and other political memorabilia. Lucy plans to hold them for ten years and then sell them for many times their present value. She does not have the room in her cramped apartment to keep them, so she crates them up and takes them to a friend for safekeeping. The friend gives her a receipt that says simply: “Received from Lucy, five cartons; to be stored for ten years at $25 per year.” Although a document of title, the receipt is not negotiable. Two years later, a browser happens on Lucy’s crates, discovers their contents, and offers the friend $1,000 for them. Figuring Lucy will forget all about them, the friend sells them. As it happens, Lucy comes by a week later to check on her memorabilia, discovers what her former friend has done, and sues the browser for their return. Lucy would prevail. Now suppose instead that the friend, who has authority from Lucy to store the goods, takes the cartons to the Trusty Storage Company, receives a negotiable warehouse receipt (“deliver to bearer five cartons”), and then negotiates the receipt. This time Lucy would be out of luck. The bona fide purchaser from her friend would cut off Lucy’s right to recover the goods, even though the friend never had good title to them.

A major purpose of the concept is to allow banks and other creditors to loan money with the right to the goods as represented on the paper as collateral. They can, in effect, accept the paper as collateral without fear that third parties will make some claim on the goods.

But even if the requirements of negotiability are met, the document of title still will confer no rights in certain cases. For example, when a thief forges the indorsement of the owner, who held negotiable warehouse receipts, the bona fide purchaser from the thief does not obtain good title. Only if the receipts were in bearer form would the purchaser prevail in a suit by the owner. Likewise, if the owner brought his goods to a repair shop that warehoused them without any authority and then sold the negotiable receipts received for them, the owner would prevail over the subsequent purchaser.

Another instance in which an apparent negotiation of a document of title will not give the bona fide purchaser superior rights occurs when a term in the document is altered without authorization. But if blanks are filled in without authority, the rule states different consequences for bills of lading and warehouse receipts. Under Section 7-306 of the UCC, any unauthorized filling in of a blank in a bill of lading leaves the bill enforceable only as it was originally. However, under Section 7-208, an unauthorized filling in of a blank in a warehouse receipt permits the good-faith purchaser with no notice that authority was lacking to treat the insertion as authorized, thus giving him good title. This section makes it dangerous for a warehouser to issue a receipt with blanks in it, because he will be liable for any losses to the owner if a good-faith purchaser takes the goods.

Finally, note that a purchaser of a document of title who is unable to get his hands on the goods—perhaps the document was forged—might have a breach of warranty action against the seller of the document. Under Section 7-507 of the UCC, a person who negotiates a document of title warrants to his immediate purchaser that the document is genuine, that he has no knowledge of any facts that would impair its validity, and that the negotiation is rightful and effective. Thus the purchaser of a forged warehouse receipt would not be entitled to recover the goods but could sue his transferor for breach of the warranty.

Key Takeaway

It is a lot easier to move pieces of paper around than goods in warehouses. Therefore commercial paper, or commodity paper, was invented: the paper represents the goods, and the paper is transferred from one person to another by negotiation. The holder signs on the back of the paper and indicates who its next holder should be (or foolishly leaves that blank); that person then has rights to the goods and, indeed, better rights. On due negotiation the transferee does not merely stand in the transferor’s shoes: the transferee takes free of defects and defenses that could have been available against the transferor. For a document of title to be a negotiable one, it must indicate that the intention of it is that it should be passed on through commerce, with the words “to bearer” or “to the order of [somebody],” and it must be duly negotiated: signed off on by its previous holder (or without any signature needed if it was bearer paper).

Exercises

- “George Baker deposited five cardboard boxes in my barn’s loft, and he can pick them up when he wants.” Is this statement a negotiable document of title?

- “George Baker deposited five cardboard boxes in my barn’s loft, and he or anybody to his order can pick them up.” Is this statement a negotiable document of title?

- Why is the concept of being a holder of duly negotiated documents of title important?

12.5 Cases

Bailments and Disclaimers of Bailee’s Liability

Carr v. Hoosier Photo Supplies, Inc.

441 N.E.2d 450 (Ind. 1982)

Givan, J.

Litigation in this cause began with the filing of a complaint in Marion Municipal Court by John R. Carr, Jr. (hereinafter “Carr”), seeking damages in the amount of $10,000 from defendants Hoosier Photo Supplies, Inc. (hereinafter “Hoosier”) and Eastman Kodak Company (hereinafter “Kodak”). Carr was the beneficiary of a judgment in the amount of $1,013.60. Both sides appealed. The Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court in its entirety.

The facts were established by stipulation agreement between the parties and thus are not in dispute. In the late spring or early summer of 1970, Carr purchased some Kodak film from a retailer not a party to this action, including four rolls of Kodak Ektachrome-X 135 slide film that are the subject matter of this dispute. During the month of August, 1970, Carr and his family vacationed in Europe. Using his own camera Carr took a great many photographs of the sites they saw, using among others the four rolls of film referred to earlier. Upon their return to the United States, Carr took a total of eighteen [18] rolls of exposed film to Hoosier to be developed. Only fourteen [14] of the rolls were returned to Carr after processing. All efforts to find the missing rolls or the pictures developed from them were unsuccessful. Litigation commenced when the parties were unable to negotiate a settlement.

The film Carr purchased, manufactured by Kodak, is distributed in boxes on which there is printed the following legend:

READ THIS NOTICE

This film will be replaced if defective in manufacture, labeling, or packaging, or if damaged or lost by us or any subsidiary company even though by negligence or other fault. Except for such replacement, the sale, processing, or other handling of this film for any purpose is without other warranty of liability.

In the stipulation of facts it was agreed though Carr never read this notice on the packages of film he bought, he knew there was printed on such packages “a limitation of liability similar or identical to the Eastman Kodak limitation of liability.” The source of Carr’s knowledge was agreed to be his years of experience as an attorney and as an amateur photographer.

When Carr took all eighteen [18] rolls of exposed film to Hoosier for processing, he was given a receipt for each roll. Each receipt contained the following language printed on the back side:

Although film price does not include processing by Kodak, the return of any film or print to us for processing or any other purpose, will constitute an agreement by you that if any such film or print is damaged or lost by us or any subsidiary company, even though by negligence or other fault, it will be replaced with an equivalent amount of Kodak film and processing and, except for such replacement, the handling of such film or prints by us for any purpose is without other warranty or liability.

Again, it was agreed though Carr did not read this notice he was aware Hoosier “[gave] to their customers at the time of accepting film for processing, receipts on which there are printed limitations of liability similar or identical to the limitation of liability printed on each receipt received by Carr from Hoosier Photo.”

It was stipulated upon receipt of the eighteen [18] rolls of exposed film only fourteen [14] were returned to Hoosier by Kodak after processing. Finally, it was stipulated the four rolls of film were lost by either Hoosier or Kodak.…

That either Kodak or Hoosier breached the bailment contract, by negligently losing the four rolls of film, was established in the stipulated agreement of facts. Therefore, the next issue raised is whether either or both, Hoosier or Kodak, may limit their liability as reflected on the film packages and receipts.…

[A] prerequisite to finding a limitation of liability clause in a contract unconscionable and therefore void is a showing of disparity in bargaining power in favor of the party whose liability is thus limited.…In the case at bar the stipulated facts foreclose a finding of disparate bargaining power between the parties or lack of knowledge or understanding of the liability clause by Carr. The facts show Carr is an experienced attorney who practices in the field of business law. He is hardly in a position comparable to that of the plaintiff in Weaver, supra. Moreover, it was stipulated he was aware of the limitation of liability on both the film packages and the receipts. We believe these crucial facts belie a finding of disparate bargaining power working to Carr’s disadvantage.

Contrary to Carr’s assertions, he was not in a “take it or leave it position” in that he had no choice but to accept the limitation of liability terms of the contract. As cross-appellants Hoosier and Kodak correctly point out, Carr and other photographers like him do have some choice in the matter of film processing. They can, for one, undertake to develop their film themselves. They can also go to independent film laboratories not a part of the Kodak Company. We do not see the availability of processing as limited to Kodak.…

We hold the limitation of liability clauses operating in favor of Hoosier and Kodak were assented to by Carr; they were not unconscionable or void. Carr is, therefore, bound by such terms and is limited in his remedy to recovery of the cost of four boxes of unexposed Kodak Ektachrome-X 135 slide film.

The Court of Appeals’ opinion in this case is hereby vacated. The cause is remanded to the trial court with instructions to enter a judgment in favor of appellant, John R. Carr, Jr., in the amount of $13.60, plus interest. Each party is to bear its own costs.

Hunter and Pivarnik, JJ., concur. Prentice, J., concurs in result without opinion.

DeBruler, J., dissenting.

…As a general rule the law does not permit professional bailees to escape or diminish liability for their own negligence by posting signs or handing out receipts. [Citations] The statements on the film box and claim check used by Kodak and Hoosier Photo are in all respects like the printed forms of similar import which commonly appear on packages, signs, chits, tickets, tokens and receipts with which we are all bombarded daily. No one does, or can reasonably be expected, to take the time to carefully read the front, back, and sides of such things. We all know their gist anyway.

The distinguished trial judge below characterizes these statements before us as “mere notices” and concludes that plaintiff below did not “assent” to them so as to render them a binding part of the bailment contract. Implicit here is the recognition of the exception to the general rule regarding such notices, namely, that they may attain the dignity of a special contract limiting liability where the bailor overtly assents to their terms. [Citations] To assent to provisions of this sort requires more than simply placing the goods into the hands of the bailee and taking back a receipt or claim check. Such acts are as probative of ignorance as they are of knowledge. However, according to the agreed statement of facts, plaintiff Carr “knew” by past experience that the claim checks carried the limitation of liability statements, but he did not read them and was unaware of the specific language in them. There is nothing in this agreed statement that Carr recalled this knowledge to present consciousness at the time of these transactions. Obviously we all know many things which we do not recall or remember at any given time. The assent required by law is more than this; it is, I believe, to perform an act of understanding. There is no evidence of that here.