This is “Introduction to Sustainable Business and Sustainable Business Core Concepts and Frameworks”, chapter 1 from the book Sustainable Business Cases (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 1 Introduction to Sustainable Business and Sustainable Business Core Concepts and Frameworks

Google Invests $39 Million in Wind Farms

In 2010, Google invested $38.8 million in two North Dakota wind farms built by NextEra Energy Resources. These wind farms generate 169.5 MW of electricity, enough to power 55,000 homes. Google’s investment represents a minority interest in the $190 million financing of the projects. The two wind farms had already been built, but Google said that its investment would provide funds for NextEra to invest in additional renewable energy projects. Google’s investment is structured as a “tax equity investment” where it will earn a return based on tax credits—a direct offset of federal taxes that Google would otherwise need to pay—for renewable energy projects, Google spokesman Jamie Yood said the energy from the wind farms would not be used to power Google’s data centers, which consume large amounts of electricity. Mr. Yood said that Google’s primary goal was to earn a return from its investment but that the company also is looking to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy. Renewable energy comes from sources such as solar panels and wind turbines to generate energy as opposed to other sources used such as coal or oil. Renewable energy typically has a much lower impact on the environment depending on the type and often emits little to no pollution.

Conscious of its high electricity bills and its impact on the environment, Google has long had an interest in renewable energy. Renewable energy projects at Google range from a large solar power installation on its campus, to the promotion of plug-in hybrids, to investments in renewable energy start-up companies like eSolar. Google has also worked on making its data centers more energy efficient, consume less electricity while still handling the same amount of data requests, and has developed technologies to let people monitor their home energy use. But as of 2010, the company had yet to live up to its promise to help to finance the generation of renewable energy. “We’re aiming to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy—in a way that makes good business sense, too,” Rick Needham, green business operations manager at Google, wrote on the company’s blog.

Source: Miguel Helft, “Google Invests $39 Million in Wind Farms,” New York Times, May 3, 2010.

© Thinkstock

1.1 Introduction

Learning Objectives

- Understand that businesses are increasingly acting with concern for the environment and society.

- Comprehend that business can play a positive role in helping to solve the world’s environmental and social problems.

- Appreciate that business interest in sustainability has been motivated by profit-making opportunities associated with sustainable business practices.

- Understand that this book focuses on sustainable business case studies in the United States.

Why would Google invest in wind farms that will not provide any energy for its high-energy-consuming data centers? Founded in 1998, Google runs the world’s most popular Internet search engine. It’s a position that has earned Google high profits and has given it huge influence over the online world. Then why would it take a risky investment of millions of dollars on an activity outside its core business? And why would the US government provide tax credits to Google and other private companies to invest in renewable energy? Can’t the private market and profit-making interests of private businesses ensure that an adequate supply of renewable energy is produced in the United States and globally?

All businesses, including Google, must focus on their economic performance and ensure they are profitable and provide an attractive return on investment for their owners and investors. Without this, businesses cannot continue as ongoing entities. For Google and other companies, their most important “bottom line” is their own economic bottom line, which is their profitability, or revenue, minus expenses.

Yet it is clear from Google’s investment in wind farms and the activities of private companies all around the globe that many of today’s business leaders look beyond their own annual economic bottom line and act with concern for how their business activities affect the environment and the very existence and sustainabilityIn the natural world, sustainability is the characteristic of a healthy, diverse ecosystem to endure over time. In terms of our society, sustainability is a state of human satisfaction and prosperity that exists from generation to generation brought on through the balanced interaction of society, environment, and economics. of the world’s physical and human resources and capabilities. This is what this book is about.

All companies must operate legally and achieve profitability to continue as ongoing entities. All companies also embed and reflect in their decision making and activities the values and priorities of their owners, key managers, employees, and other stakeholders. As will be highlighted in this book, some companies, such as BP prior to the Gulf oil spill in 2010, focus on annual profitability and investment returns to owners more than others. Other companies, including Google, give priority to other values (besides profit making) and take into consideration environmental and sustainability concerns along with concern for annual profits. And other firms, such as Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, Oakhurst Dairy, Simply Green, Timberland, Pax World, Seventh Generation, and Stonyfield Farms (as described in Chapter 7 "Case: Sustainable Business Entrepreneurship: Simply Green Biofuels" through Chapter 13 "Case: Strategic Mission–Driven Sustainable Business: Stonyfield Yogurt" in this textbook), more fully integrate sustainable business practices into their mission and corporate strategy and try to gain a competitive advantage by doing this.

This book describes what it means for a business to be sustainable and to engage in sustainable business practices and why a business would choose to act in a more sustainable manner. The book will be of interest to students who are interested in understanding the role of sustainable businesses in the economy and society, in addressing environmental concerns, and in working for or starting their own sustainable businesses.

The focus of the book is on the experience, opportunities, and challenges for sustainable businesses in the United States. While the book does not provide detailed international examples in its in-depth case chapters (Chapter 7 "Case: Sustainable Business Entrepreneurship: Simply Green Biofuels" through Chapter 13 "Case: Strategic Mission–Driven Sustainable Business: Stonyfield Yogurt"), it does discuss the opportunities and challenges of US-based sustainable businesses operating globally, specifically in Chapter 5 "Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Sustainable Business" and Chapter 13 "Case: Strategic Mission–Driven Sustainable Business: Stonyfield Yogurt". The objective is to expose students in the fields of business, science, public policy, and others to the ideals, opportunities, and challenges of sustainable business practices with examples and lessons from a diverse group of companies in different industries.

Sidebar

What Is Sustainability?

Sustainability is meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This is a commonly referenced definition, developed by the Norwegian prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland for the 1987 report “Our Common Future,” produced by the World Commission on Environment and Development under the direction of the United Nations.

Sidebar

What Does It Mean to Be Green and Is That the Same as Sustainable?

And what does “green” mean and how does it relate to sustainability? Green is a term widely used to describe buildings, products (of all types, including cars, food, computers, etc.), and services designed, manufactured, or constructed with minimal negative impact on the environment and with an emphasis on conservation of resources, energy efficiency, and product safety. Being “green” can help to preserve and sustain society’s resources.

Key Takeaways

- Businesses are increasingly engaging in activities with concern for the environment and society.

- Businesses are engaging in these activities because they recognize they can play a positive role in helping to solve the world’s environmental and social problems.

- Businesses are also interested in sustainability because of market and profit-making opportunities associated with sustainable business practices.

- This book intends to explore the opportunities and challenges for sustainable business in the United States primarily through case studies.

Exercises

-

Answer the following questions:

- Do you think that Google would have invested in the two North Dakota wind energy projects if they did not receive tax credits (a government incentive that reduces the federal taxes that they owe)? Why or why not?

- Besides tax credits, what are some of the other benefits that Google could obtain by investing in the wind energy projects?

- Based on this article, do you think that it is wise for Google to continue investing in potential future renewable energy projects given that their core successful business model is based on web searches and not providing energy?

- Search on the web and find three other examples of companies investing in renewable energy projects, even though those companies’ core business models do not involve energy production. Describe the business, their core business model, and the type of project they invested in.

1.2 Overview of Sustainable Business

Learning Objectives

- Explain what it means to be a sustainable business and the relationship of profitability and sustainability.

- Understand what is meant by the triple bottom line for businesses in relation to sustainability.

- Describe what is meant by enlightened self-interest and provide an example of how it applies to business.

A focus on sustainability (for private businesses) can be thought of as a management strategy that helps businesses set goals and prioritize resource allocations. Sustainability at the private business level can first be thought of primarily in terms of financial sustainability—that is, the ability of private firms to generate profits and cash flow to sustain business operations. For-profit businesses—first and foremost—must focus on their economic bottom line. A company that earns a profit is providing a good or service that is valued by society. Consumers and businesses do not pay for products and services that do not provide them with value or benefits above the cost of the product or service to them (or else they would not have made the free decision to purchase that product or service). Therefore, at a basic level, if a business is profitable, it is having a net positive social impact. This is assuming that the business has no external impact on the environment or society.

However, there are companies that are profitable in the short term that are having a long-term net negative impact. For example, a lumber company that owns timber reserves could harvest all of its timber resources in one year generating a significant profit for that one year. However, if in doing this the company ignored the costs and losses associated with destroying the forest and the ability of the forest to continue to produce timber, then the net impact could be negative. By depleting the resource base of the company, short-term gain can lead to long-term financial failure for the company. This example highlights the need for sustainable thinking in business. For business to be sustainable in a financial sense, businesses must increasingly consider the longer term and broader consequences of decisions.

Beyond just the company’s own bottom line, a “next step” for businesses is to consider not only their own long-term financial performance but also broader societal environmental and social impacts. This so-called triple bottom lineMeasuring a company’s impact on people, planet, and profit (bottom line). (TBL) considers business from economic, environmental, and social perspectives and measures business performance based on net impact on profit, people, and planet. This approach to business will be increasingly relevant to students of business and in other fields as global populations and demand for energy, water, and other resources increase and our planet faces resource shortages. Over the next fifty years, the world’s population is expected to grow from 6.8 billion to 9.5 billion, and the demand for energy and other resources will follow.

The primary aspects of sustainability considered in this book are profit and planet. Much of the framework and concepts relevant for environmental sustainability also apply to social sustainability and several of the case study chapters highlight examples of businesses, such as Seventh Generation, Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, Stonyfield, and Simply Green, incorporating social issues into their decision making.

© Thinkstock

For businesses that consider TBL and sustainable business practices, it is increasingly not about deciding whether to focus on (earning) profits, or (saving) the planet, or (caring about) people. Instead, it’s about focusing on all three. When McDonald’s reduces the packaging with their food, they help the environment, contribute to public health (by reducing toxics in the atmosphere), and they also help their economic bottom line. Enlightened self-interestA business philosophy where a business does “well” (is successful financially) by doing “good” (helping others and the environment). occurs when companies (or individuals) help others and, in the process, help themselves. When McDonald’s uses less packaging for their hamburgers, French fries, and other food items than in the past, this reduces their costs of materials and disposal costs while at the same time it helps the environment. Reducing packaging is an example of a sustainable business practice that can benefit a private company and also society at large.

In the longer term, all businesses rely on the sustainability of societies’ resources, including energy, food, and material resources, for their success and survival. Thus it can be in all businesses long-term interest to act with concern for the sustainability of society’s resources.

Sidebar

Doing Well and Doing Good

Companies that act with enlightened self-interest are also commonly referred to as doing well (for themselves) at the same time that they are doing good (good things for others), or “doing well by doing good.”

Gulf Oil Spill

The 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil spill—the disaster that quickly became the largest oil spill in US history“Estimates Suggest Spill Is Biggest in U.S. History,” New York Times, May 28, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/28/us/28flow.html?ref=us.—offers a vivid example of how sustainability issues affect profits, people, and planet. The spill (as of June 2010) was estimated to have leaked at least triple the amount of oil as compared to the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska during 1989.

BP put itself into a very difficult and controversial position. BP had a history of accidents that were harbingers of the Gulf spill, including having to pay $25 million in fines for a spill on the north shore of Alaska in 2006. Then in 2010 under financial and time pressure, BP failed to properly cap it’s Gulf Coast well from which they had been drilling. BP hastened through procedures to detect excess gas in the well, skipped quality tests of the cement structure around the pipe, and even assigned an inexperienced manager to oversee final well tests.“BP Decisions Set Stage for Disaster,” Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704026204575266560930780190.html?KEYWORDS=It+was+a+ difficult+drill+from+the+start. While most of the company’s actions were not best practices, they were within acceptable industry standards and believed by many to be legal. The oil released from the uncapped well threatened the valued ecosystem of the Gulf in very serious ways. The oil adversely impacted populations of fish, marine birds, and other aquatic wildlife and threatened fragile wetland ecosystems.

BP could have at some short-term cost avoided the Gulf oil spill. Instead, the company chose not to put in place some safety features and then delayed responding to signals that there were problems in the pipeline, which resulted in a major pipeline break with catastrophic implications for the environment and significant economic costs to the company. From when the drilling rig exploded on April 20 through June 2, 2010, the company lost a third of its market value, or about $75 billion, and the company had spent almost $1 billion on cleanup efforts. One analyst calculated that in a worst-case scenario, BP’s cleanup liability would be around $14 billion, which would account for the entire loss of all fishing and tourism revenues for coastal states closest to the spill.Jad Mouawad and John Schwartz, “Cleanup Costs and Lawsuits Rattle BP’s Investors,” New York Times, June 1, 2010.

The BP Gulf of Mexico situation highlights why sustainable business is of increasing interest and importance to students of business and also students in science, government, public policy, planning, and other fields.

Source: Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BP_Oil_spill_Chandeleur_IslandsLA.jpg.

Key Takeaways

- Sustainable business involves making decisions and taking actions that consider the long-term impact of the business on society and the environment while still maintaining profitability.

- People, planet, and profit—also known as the triple bottom line—are the three areas that businesses interested in sustainability measure their impacts. This varies from traditional businesses, which are predominantly focused on profits as their measure of success.

- Enlightened self-interest refers to business as taking actions that are good for the environment and society but that also help make the business better off.

- The Gulf oil spill provides an example of how acting in an unsustainable manner with a short-term focus on profit can have significant long-term negative impact for society, the environment, and the economy—including BP, which was seeking to maximize its profit.

Exercises

- Search the web for an article that discusses an action that a company took that benefited the environment or others outside of the company and that also had a financial benefit for the company. Be prepared to discuss what the action was, the financial benefit the company achieved by taking action, and how that action led to the financial benefit.

- Some have argued that the purpose of a business is to earn a profit and that is its only goal. Do you agree with that? Discuss what you feel are some pros and cons of a business expanding its focus to consider the effect of its actions on “people” and “planet.”

1.3 What Does It Mean to Be a Sustainable Business?

Learning Objectives

- Identify what it means to be a sustainable business.

- Define what constitutes sustainable business practices and provide examples.

- Describe the main motivations for engagement in sustainable business practices.

- Discuss the barriers that businesses can encounter in adopting sustainable business practices.

The sustainable business perspective takes into account not only profits and returns on investment but also how business operations affect the environment, natural resources, and future generations. Sustainability at the business level can be thought of as taking steps, such as recycling and conserving nonrenewable material and energy use to reduce the negative impact of a business’s operations on the environment. While managing operations to reduce negative environmental impact is an important part of business sustainability, these types of activities are increasingly part of a deeper strategic perspective on sustainability for businesses.

Businesses implement sustainability in their organization for a variety of reasons. The benefits from pursuing sustainability can include the following:

- Reduction of energy and materials use and waste and the costs associated with these. McDonald’s reducing the packaging with hamburgers and French fries is an example of this.

- Lowering of legal risks and insurance costs. For example, BP, with some investment in safety features to protect against environmental disaster, could have avoided huge liability costs that will be associated with Gulf of Mexico oil spill.

- Differentiation of product or services and brand. Companies such as Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (see Chapter 9 "Case: Brewing a Better World: Sustainable Supply Chain Management at Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, Inc.") and Stonyfield Farm (see Chapter 13 "Case: Strategic Mission–Driven Sustainable Business: Stonyfield Yogurt") have differentiated their brands and increased consumer awareness and sales of products with their focus on sustainability.

- Drive toward innovation to create new products and serve new markets. Seventh Generation (see Chapter 8 "Case: Marketing Sustainability: Seventh Generation Creating a Green Household Consumer Product") developed new products to address environmental concerns of households and positioned themselves as the leader in that market, sustainable consumer household products.

- Improvement of company image and reputation with consumers, particularly the increasing numbers of consumers who are concerned about the environment and their own impact on the environment (see Chapter 6 "Sustainable Business Marketing" for more discussion of consumer preferences for sustainable products and services).

- Enhancement of investor interest. Increasing numbers of investors take into consideration company sustainability practices when they make their decisions how to invest (see Chapter 12 "Case: Sustainable Investing: Pax World Helping Investors Change the World"). Companies that act with concern for social and environmental matters operate at lower risk and their future growth rates can be positively affected. Both of these are positive factors for investors.

- Increase attraction and retention of employees who care about the environment and sustainability.

The most important factors that motivate companies to become more sustainable are internal. This includes the number one objective of companies—to maximize profits. The beliefs and personal values of management and employees can also significantly influence engagement in sustainable business practices. Many managers and employees have an interest in sustainability and its benefits to society. They can move the company forward on sustainable business practices because it’s the right thing to do—that is, owners, managers, and employees believe that sustainable business practices are the moral and ethically right thing to do. Companies with senior management and owners who are committed to sustainable business practices for ethical reasons are more likely to put in place sustainable business practices even without having a detailed assessment of how it will affect revenue, costs, and profitability.

There are also important external factors that influence a business’s decision to become more sustainable, including governmental laws and regulations and consumer and investor interests and expectations. These external factors are strongly influenced by societal trends and values, demographics, new knowledge (including scientific findings, highlighted in Chapter 2 "The Science of Sustainability"), and the media.

Sustainable businesses strive to maximize their net social contribution by embracing the opportunities and managing the risks that result from an organization’s economic, environmental, and social impacts. In many respects, the best measure of business contributions to society are profits. Profits represent the value of products and services that companies provide (as reflected in the prices that consumers are willing to pay for a company’s products and services) minus the direct costs of producing the products or services.

However, private market transactionsThe purchase or sales of goods and services between businesses and other businesses or consumers. do not take into account so-called external costsA cost experienced by a party that is not directly involved in a private market transaction. to market transactions. For example, the external costs associated with the production of electricity from coal include climate change damage costs associated with the emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and damage costs (such as impacts on health, crops, etc.) associated with other air pollutants (such as nitrous oxide and sulfur dioxide). These pollutants threaten the future sustainability of natural resources and have a cost, and these costs are not included in the price of energy and not passed on to consumers. Thus market prices do not reflect costs to society perfectly, and this can result in significant differences between profits and the net societal contributions of companies and can present challenges to businesses interested in maximizing their net positive social impact and acting in a sustainable way. Government often acts to address market failure and to reduce the external costs associated with pollution and environmental damage incurred in market activities. Controlling negative externalities is used to justify government restrictions, regulations, taxes, and fees imposed on businesses (see detailed discussion in Chapter 3 "Government, Public Policy, and Sustainable Business"). Governments at the federal, state, and local level in the United States have acted on this. In general, European nations have been more active in trying to address market failures and trying to control external costs associated with market activities in environmental, social, and other arenas than the United States.

Sidebar

The Role of Government Policies in Sustainable Business

Government policies, such as a carbon tax (a tax on pollution), can address externalities by having companies and consumers internalize the costs associated with what were externalities. This can help move private companies focused on profits to activities that better reflect their net social contributions. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 2 "The Science of Sustainability".

The challenge of acting in a sustainable way in a private market economy in which the external costs, including those associated with carbon dioxide emissions, are not included is reflected in the Green Mountain Coffee statement that follows.

Source: Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ElSalvadorfairtradecoffee.jpg.

And while we are committed to achieving greater sustainability in our products and practices, we compete in a marketplace where economic value drives demand. This is the challenge of trying to do the right thing in a commercial system that does not yet fully account for its global impact.“Building Demand for Sustainable Products,” Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, http://www.gmcr.com/csr/PromotingSustainableCoffee.aspx.

A challenging task for Green Mountain Coffee and other businesses today is to effectively integrate the traditional business performance objectives (profit maximization) with striving to continuously increase the long-term societal value of their organizations. This challenge is represented by the mission statement from the CEO of Ford Motor Company:

To sustain our Company, meet our responsibilities and contribute to tackling global sustainability issues, we must operate at a profit.“For a More Sustainable Future: Connecting with Society, Ford Motor Company Sustainability Report 2006/7,” Ford Motor Company, http://corporate.ford.com/our-company/our-company-news/our-company-news-detail/sustainability-reports-archive. I have long believed that environmental sustainability is the most important issue facing businesses in the 21st century. Fortunately, unlike 20 years ago, or even five years ago, a growing number of people in our industry now agree, and we are doing something about it. Our vision for the 21st century is to provide sustainable transportation that is affordable in every sense of the word: socially, environmentally and economically…I am convinced that our vision makes sense from a business point of view as well as an ethical one. Climate change may be the first sustainability issue to fundamentally reshape our business, but it will not be the last. How we anticipate and respond to issues like human rights, the mobility divide, resource scarcity and poverty will determine our future success.“2007/8 Blueprint for Sustainability,” Ford Motor Company, http://corporate.ford.com/our-company/our-company-news/our-company-news-detail/sustainability-reports-archive.

How Do Businesses View Sustainability? How Important Is It to Businesses?

The actions and statements of Green Mountain Coffee, Ford Motors, and many leading companies globally demonstrate business interest in sustainability. The interest in sustainability is often written, as with the Ford Motor Company example previously mentioned, in corporate mission or value statements. The exact wording and nature of the commitment to sustainability varies but it is represented in an increasing number of the public documents of corporations.

There is significant variance in how deeply and sincerely companies are committed to their mission and in how much the value statements influence actual company practice. However, just that the statements are made and made public for all to read suggests that sustainability is an important issue for an increasing number of businesses. See the following examples from Hewlett Packard (HP) and Walmart, respectively.

Environmental sustainability is one of the five focus areas of HP’s global citizenship strategy, reflecting our goal to be the world’s most environmentally responsible IT company. This commitment is more than a virtuous aspiration—it is integral to the ongoing success of our business. Our drive to improve HP’s overall environmental performance helps us capitalize on emerging market opportunities, respond to stakeholder expectations and even shape the future of the emerging low-carbon, resource-efficient global economy. It also pushes us to reduce the footprint of our operations, improve the performance of our products and services across their entire life cycle, and innovative new solutions that create efficiencies, reduce costs and differentiate our brand.“HP Environmental Goals,” Hewlett-Packard, http://www.hp.com/hpinfo/globalcitizenship/environment/commitment/goals.html.

The fact is sustainability at Walmart isn’t a stand-alone issue that’s separate from or unrelated to our business. It’s not an abstract or philanthropic program. We don’t even see it as corporate social responsibility. Sustainability is built into our business. It’s completely aligned with our model, our mission and our culture. Simply put, sustainability is built into our business because it’s so good for our business.“Walmart 2009 Global Sustainability Report,” Walmart, http://walmartstores.com/sites/sustainabilityreport/2009/letterMikeDuke.html.

Sustainability 360 is the framework we are using to achieve our goals and bring sustainable solutions to our more than 2 million associates, more than 100,000 suppliers and the more than 200 million customers and members we serve each week. Sustainability 360 lives within every aspect of our business, in every country where we operate, within every salaried associate’s job description, and extends beyond our walls to our suppliers, products and customers.“Overview,” Walmart, http://walmartstores.com/sites/sustainabilityreport/2009/en_overview.html.

These are just a few examples. Among companies from the “Global Top 1,000” that responded to a 2008 survey, about three-quarters (73 percent) have corporate sustainability on their board’s agenda and almost all (94 percent) indicate that a corporate sustainability strategy can result in better financial performance. But significantly, only about one in ten (11 percent) of the “Global Top 1,000” are actually implementing a corporate sustainability strategy.M. Van Marrewijk, “Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability,” Journal of Business Ethics 44, nos. 2–3 (2003).

In a separate 2009 MIT study with the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) titled The Business of Sustainability, of 1,500 corporate executives surveyed, an overwhelming majority believe that sustainability-related issues are having or will soon have a material impact on their business. Yet relatively few of the companies are taking decisive action to address such issues.

While about 45 percent said their organizations were pursuing “basic sustainability strategies,” such as reducing or eliminating emissions, reducing toxicity or harmful chemicals, improving efficiency in packaging, or designing products or processes for reuse or recycling, less than a third of survey respondents said that their company has developed a clear business case for addressing sustainability. The majority of sustainability actions undertaken to date appear to be limited to those necessary to meet legal and regulatory requirements. The MIT research did indicate that once companies begin to pursue sustainability initiatives, they tend to unearth opportunities to reduce costs, create new revenue streams, and develop more innovative business models.M. Hopkins, “The Business of Sustainability,” MIT Sloan Management Review 51, no. 1 (2009), http://mitsloan.mit.edu/newsroom/2009-smrsustainability.php.

It is not only larger companies that are interested and acting on sustainability. Many smaller and start-up companies are focused on sustainability, with some entrepreneurs, such as Jeffrey Hollender, the founder of Seventh Generation (see Chapter 8 "Case: Marketing Sustainability: Seventh Generation Creating a Green Household Consumer Product"), and Andrew Kellar, the founder of Simply Green (see Chapter 7 "Case: Sustainable Business Entrepreneurship: Simply Green Biofuels"), founding their ventures based on their commitment to sustainability; see Chapter 5 "Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Sustainable Business" for a broader discussion of sustainable business entrepreneurship.

What Holds Companies Back from Implementing Sustainable Business Practices?

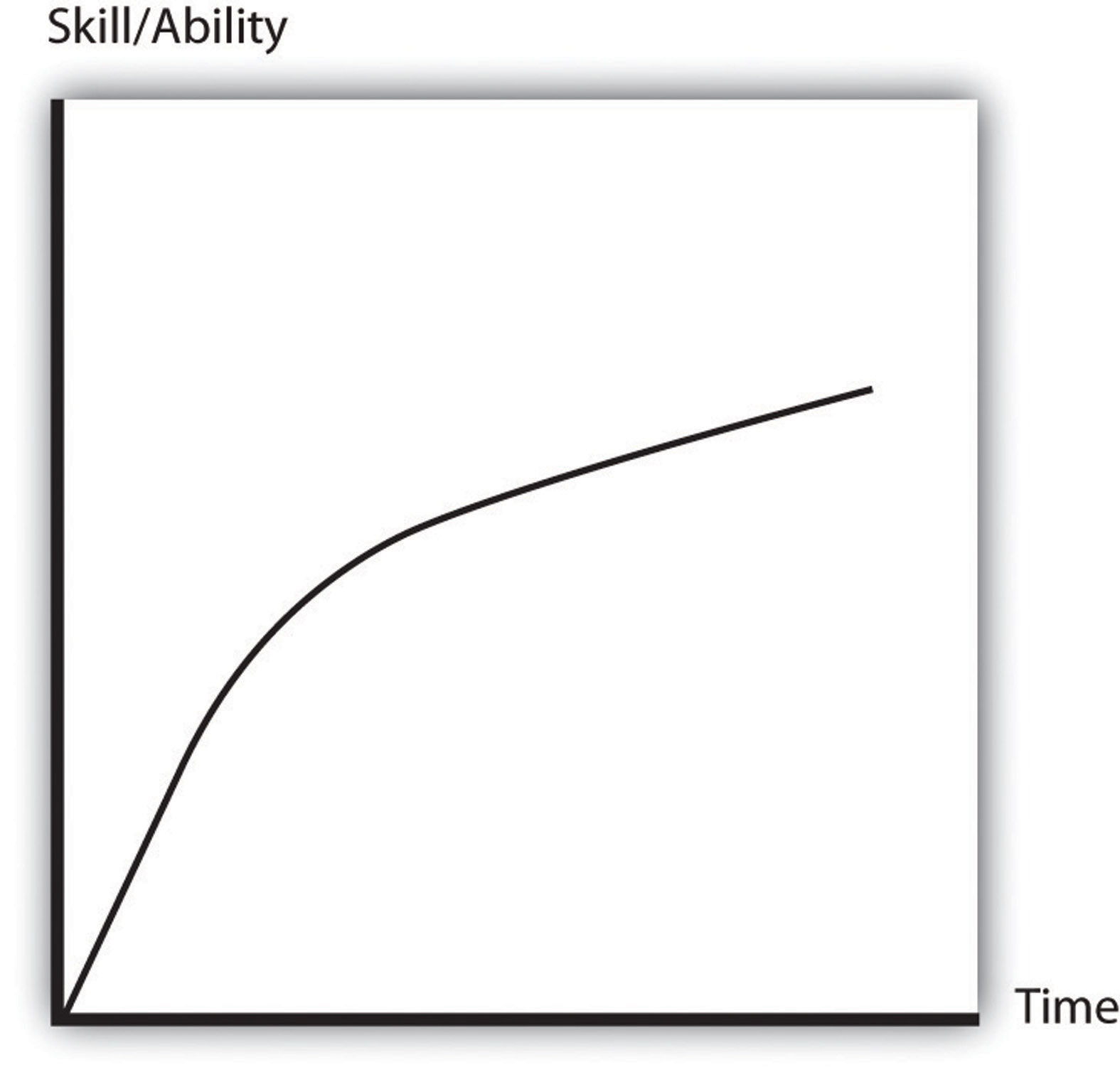

There are many factors contributing to private companies not implementing corporate sustainability practices. There is a learning curveAlso known as the experience curve; it represents the time it takes for a person or business to learn new technologies, skills, or knowledge. associated with sustainable business practices—ranging from basic compliance to completely changing the business environment—and in many respects a large majority of businesses are just at the initial learning stage.

Figure 1.1 Learning Curve“Rant: Reinventing the Wheel,” My 4-Hour Workweek (blog), February 13, 2010, http://www.my4hrworkweek.com/rant-reinventing-wheel.

Three of the major barriers that impede decisive corporate action are a lack of understanding of what sustainability is and what it means to an enterprise, difficulty modeling the business case for sustainability, and flaws in execution, even after a plan has been developed.

The learning curve on sustainable business practices is steep, and it often entails significant risks and uncertainty. Any change in company practice involves taking on some risk and uncertainty, and this is heightened when taking on something for which the benefits are not clear and are dependent on changing laws, regulations (see Chapter 3 "Government, Public Policy, and Sustainable Business"), and consumer values and interests. But the risks of failing to act decisively are growing, according to many of the thought leaders interviewed in the MIT study.

Sidebar

Learning Curve

The learning curve refers to a graphical representation of learning. The curve represents the initial difficulty of learning something and how there is a lot to learn after the initial learning. In the case of learning about sustainable business practice, managers often quickly learn enough to be interested in it, but then the learning curve is high (steep), and there is a lot to learn to ensure that the sustainable practice serves the interests of the business entity.

There are many different definitions of and frameworks for considering sustainability, and this can confuse businesses considering engaging in more sustainable practices. The confusion and lack of clear definition can result in inaction or a slow response on sustainability. Over 50 percent of respondents to the “Global Top 1,000” sustainability survey stated a need for a better framework for understanding sustainability. Many companies struggle to model the business case for sustainability and need help in doing this. Some companies are making progress on framing and reporting on sustainable business practices and quantifying the impacts of their sustainability efforts internally and externally; see Chapter 4 "Accountability for Sustainability" and Chapter 11 "Case: Accounting for Sustainability: How Does Timberland Do It and Why?".

Another contributing barrier to the implementation of sustainable business practices is the ambitious agenda and enthusiasm of the strongest advocates for sustainability. Since sustainability stresses the interconnectivity of everything, many groups have adopted it. While many of the advocates for sustainability are well intended, they often do not appreciate the difficulties and challenges of implementing sustainable business practices. This leads some businesses to resist the call to put in place sustainable business practices, as the economic and environmental benefits of some of the practices may be exaggerated and oversold, and the commitment asked for by advocates can be perceived as too deep, too costly, and too fast for many companies to accept.

Another contributing factor to corporate inaction on sustainability is that some businesses have acted on sustainability only for public relations purposes and to gain favor with consumers, investors, and government agencies without undertaking any practices with significant benefit to the environment or society. This can discourage businesses that have a sincere interest in sustainable business practice as they fear that they will be branded as greenwashingThe practice of making an unsubstantiated or misleading claim about the environmental benefits of a product, service, or technology. if they are not successful in their efforts.

© Thinkstock

Sidebar

What Is Greenwashing?

The term used to describe insincere engagement in sustainable business is greenwashing. It was first used by New York environmentalist Jay Westerveld who criticized the hotel practice of placing green “save the environment” cards in each room promoting the reuse of guest towels. The hotel example is especially noteworthy given that most hotels have poor waste management programs, specifically with little or no recycling. The term greenwashing is often used when significantly more money or time has been spent advertising being green rather than spending resources on environmentally sound practices or when the advertising misleadingly indicates a product is more green than it really is. For example, a company may make a hazardous product but put it in packaging that has images of nature on it to make it appear more environmentally friendly than it really is.

Sidebar

Walmart and Accusations of Greenwashing

Walmart has been accused of engaging in greenwashing and has taken actions to deepen their commitment to sustainability to address this accusation. It is very difficult to change a large company, and it has not been an easy task turning Walmart, the world’s largest retailer, around. But after a difficult start, the company is making progress on environmental targets. The company has succeeded in opening an energy efficient prototype in every market globally, and since 2005, Walmart has improved its fleet efficiency by 60 percent. The company has also cut emissions generated at its existing stores, clubs, and distribution centers by 5.1 percent since 2005, putting the company at about 25 percent toward its 2012 goal. However, the company’s absolute carbon footprint has continued to grow, despite it improving facility performance and reducing its carbon intensity over the last two years. In response, the company set the 2015 goal of avoiding twenty million metric tons, which is about 1.5 times the projected cumulative growth of its emissions over the next five years.“Walmart’s Sustainability Report Reveals Successes, Shortcomings,” Greenbiz.com, http://www.greenbiz.com/news/2010/05/12/walmarts-sustainability-report-reveals-successes-shortcomings%20#ixzz0phcjFwWK.

Initial efforts in sustainability in which businesses are just at the initial learning stages and trying to figure out what to do can be confused with greenwashing. This might well have been the case at Walmart and other companies at first. And the steep learning curve and the risks of being accused of being insincere and greenwashing can deter businesses from sustainable business practice.

Another one of the more significant barriers is that sustainability, specifically focusing on factors external to the company, may just not be high on the list of important factors for some businesses. This can be particularly true for businesses that are struggling to keep revenues above expenses and survive economically and for small businesses with limited managerial and economic resources.

And then there are the concerns over the additional costs associated with instituting a commitment to sustainability and undertaking new sustainable business practices. There are often significant upfront costs or investments required that do not have immediate financial return. Many of the potential investments in sustainable practices, including investments in energy efficiency (e.g., installing new insulation in buildings) and renewable energy (e.g., wind power) have payback periods of ten years or longer.

It is the uncertainty associated with sustainable practices that is probably one of the main barriers. For most businesses, there is already so much uncertainty in their operating environment that they do not want to add another source of uncertainty if they perceive that they do not have to. But as with the case of BP and the Gulf Coast oil spill, attention to sustainability could actually reduce uncertainty and risks for businesses.

For example, had BP been more focused on sustainable business practices, they may have asked what are the potential negative environmental and social outcomes that may come from an oil leak. They may have more fully appreciated the disastrous impact on both present and future generations in the Gulf Coast area and also the potential negative financial impacts it would have on their corporate earnings. In conducting this “what-if” analysis, a reasonable outcome of this process may have been to have more rigorous safety controls in place and also to have better disaster response technologies and resources available for their drilling projects.

Among the companies that try to implement sustainable practices, there can be difficulty, and some companies after initial efforts may pull back or resist deeper efforts. Execution may be flawed, and after failed or costly efforts, it can be difficult to overcome skepticism in organizations.

Internal to the corporation there are significant barriers to effective implementation of sustainable practices. This includes the great difficulty that many corporations experience in trying to change (there can be significant inertia) and the challenge businesses experience in institutionalizing new practices and priorities. The experience highlighted in the cases in this book will show how top-down commitment throughout a business organization is important for businesses to move toward sustainability practices.

Finally, the most significant barrier to adoption of sustainable business practices may be that many companies simply do not adequately understand sustainability and what it could mean to their company and, specifically, how it could impact their economic bottom line.

Key Takeaways

- Businesses’ main concerns are their own viability and profitability.

- Sustainable businesses also take into consideration how their activities impact society’s resources and future generations.

- Examples of sustainable business practices include efforts to reduce energy and materials use and to use renewable and nonpolluting resources.

- Some of the main motivations to engage in sustainable business practice include the legal and regulatory concerns, the potential to lower energy and material costs, the opportunity to improve reputation and sales, the founder or owner’s concerns and values, and a competitive advantage.

- Three-fourths of top company boards have given attention to sustainability, but only 10 percent are actually implementing sustainability plans. This highlights a large disconnect between interest in sustainability and actually taking steps for companies to become more sustainable.

- Significant barriers to sustainability include uncertainty involved, lack of understanding of what sustainability is, difficulty making the business case for sustainability, and failure to properly execute sustainability plans.

Exercises

- Find three articles about businesses that have adopted sustainability practices. Find an article that shows a sustainability practice that resulted in lower costs. Find an article that shows a sustainability practice that improved reputation and sales. Find an article that shows a sustainability practice that might preempt government regulation (can be local, state, or federal). Be prepared to discuss the action the company took, the benefit the company received, and how the action resulted in benefit.

- An industrial company with a history of violating its water discharge permit of pollutants decides to “go green.” It switches to a biodegradable cleaning detergent for cleaning its offices and starts a paper recycling program for its offices. The cost of the change is minimal to the company. However, the company does not change any of its water discharge practices. The company then commences a marketing campaign of national television and radio ads claiming that it is now a sustainable company. Do you think this is an example of greenwashing? Why or why not?

1.4 What Is Required for a Sustainability Perspective?

Learning Objectives

- Be able to explain what is required to have a sustainability perspective.

- Understand what it means to have a systems perspective.

- Describe why a systems perspective is useful for guiding sustainable business practices.

Sustainability and managing a business that works to contribute to sustainability requires a different perspective than many businesses currently have. Most businesses focus on profits, often with a short-term, annual, or even month-to-month focus. Sustainable business practices require a longer term and a systems perspective on how a business organization’s actions impact the environment and society. It requires business managers being mindful and considering not only the traditional business concerns, such as revenues, costs, and profits, but also the effects their actions have on the physical environment and the well-being of future generations.

A systems approachSystems are made up of components that work together for the overall objective of the whole. The systems approach is simply a way of thinking about these total systems and their components. can provide an important perspective on sustainability matters.C. West Churchman, The Systems Approach (New York: Delacorte, 1968). Societal well-being and the sustainability of societal resources are interrelated and relevant for individual businesses and industries as well as for individuals, cities and towns, nations, and the entire planet. For example, on a local community scale, a resource-dependent community economy (e.g., a fishing community in Newfoundland, Canada) cannot achieve economic sustainability if it depletes its most valuable local natural resource—fisheries. On a global scale, global economic activity (by all individuals, households, and businesses collectively) that contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions and global warming cannot be sustained if natural resources and human population and health are adversely affected and not sustained.

Starting with the most simple systems perspective we can consider the interdependence between a single company and society as taking two main forms. Every firm impacts society through its operations in the normal course of business—for example, McDonald’s with its packaging and BP with its oil drilling. These are called “inside-out” linkages.Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York: Free Press, 1985). Then there are “outside-in” linkages with external environmental and societal conditions influencing businesses. For example, McDonald’s depending on the supply of food and BP depending on the oil supply.

Another way of thinking about this system is to first think about the consequences of business, for example, how each business affects the economy, the natural environment, and the people (e.g., consumers and employees), and then to think about the context in which businesses operate in, including the natural, human, and social resources businesses depend on to operate and the legal and regulatory context businesses operate in. Systems thinking would have businesses be mindful and considerate of their operating context and consequences. And systems thinking could help business managers consider how the consequences (outcomes) of their activities affect the context in which they operate in the long term. So for example, if a timber company is depleting a forest it owns, it can think about how this will affect its operating context including its supply costs in the future.

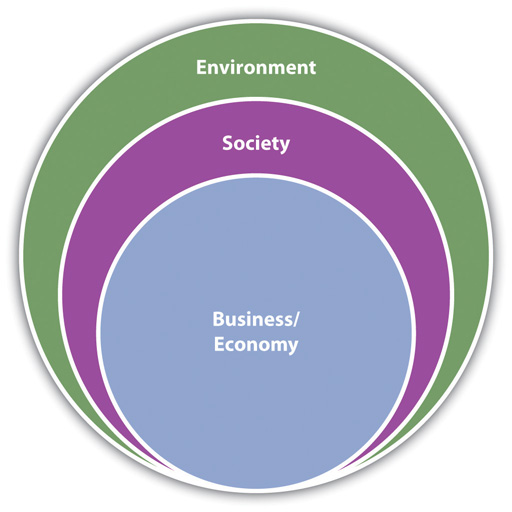

Business’s Place in Larger System: A Simple Depiction

Business and the economy are an important part of the greater social system. Businesses and the economy exist within a broader system of laws, cultures, and customs that make up human society. The global social system exists within the broader context of the earth’s environment. Businesses, the economy, and society are dependent on the earth’s natural resources.

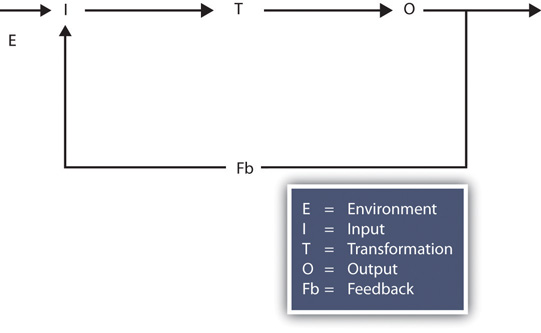

A more complex and dynamic systems approach or perspective defines a system as a set of things that affect one another within an environment and form a larger pattern that is different from any of the parts. When viewed from a systems perspective, organizations engage in the continual stages of input, throughput (processing), and output in an open or closed context. A closed systemIn a systems approach context, an organization that is isolated from the external environment. does not interact with its environment. It does not take in information and therefore is likely to atrophy—that is, to vanish. An open systemIn a systems approach context, an organization that continually interacts with its external environment. receives information, which it uses to interact dynamically with its environment. Openness increases the likelihood of survival and prosperity.

Sustainable business practices require an open systems perspective and consideration of how business actions impact not only internal operations and outcomes (such as costs, sales, and profitability) but also external outcomes—that is, the environment and the sustainability of the natural and social systems that businesses are part of.

Systems Conceptual Model

Source: A. H. Littlejohn and S. Cameron, “Supporting Strategic Cultural Change: The Strathclyde Learning Technology Initiative as a Model,” Association of Learning Technologies Journal (ALTJ) 7, no. 3 (1999): 64–75.

All the systems perspectives highlight how businesses are part of a larger system, and they all suggest the importance of businesses—as major components of the US social and economic system—being mindful and taking into consideration how their activities affect the larger system.

Key Takeaways

- Sustainable businesses require a systems perspective.

- The systems perspective enables businesses to understand their position and relationship in the larger environmental and social system, including their dependence on inputs and how their output and use of resources affects the overall system and the elements of the system.

- Without a systems perspective, businesses would not be able to understand their impact on society and the environment.

Exercises

- Do you agree or disagree with the statement “an open system is sustainable while a closed system is not”? Come up with specific examples to support your assertion.

- In your own words, define what is meant by outside-in linkages and inside-out linkages in a business context. Provide a specific example of each type of linkage.

1.5 The Business Case for Sustainability

Learning Objectives

- Understand the social responsibilities of business.

- Describe the stakeholders in corporations.

- Explain the role of consumers in motivating sustainable business practice.

While the systems perspective is useful as a conceptual framework, there is a need for more practical (and “business-oriented”) guidance on sustainable business practices. A pragmatic approach to sustainable business requires moving away from any extreme position: with one extreme having sustainability as solely an additional cost and the other having that it is always beneficial for business to do more to reduce their environmental and societal impact. Neither is particularly useful to guide business practices.

The framing of corporations and their role in society strongly affects the case for and practice of sustainable business. And there are many views of the corporation and private companies and their role/place in a private market economy.

The Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman from the University of Chicago’s School of Economics wrote about the social responsibility of business. He described business responsibility as being the achievement of profit in a legal manner. For Friedman, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud.”J. DesJardins, “Corporate Environmental Responsibility,” Journal of Business Ethics 17, no. 8 (1998).

Working from Friedman’s perspective businesses should only engage in sustainable business practices if the practices can directly contribute to their own economic bottom line or if government mandated that business engage in sustainable practices—that is, it was illegal not to do it. Friedman questioned the logic of corporate social responsibility as it had been developing at the time. He insisted that in a democratic society, government, not business, was the only legitimate vehicle for addressing social concerns. He argued that government was the best vehicle for meeting societal concerns, such as environmental sustainability, but many found it difficult to believe, given Friedman’s libertarianism, that such an argument was in good faith.

The response of management thinkers to Friedman was to develop alternative views of corporate social responsibility (CSR)A business model where societal impact is considered in business decision making. It shifts the focus from only considering the financial impact on the company when making decisions to including societal and environmental impacts. This business model shares many similarities to the business model of sustainability for companies.. Two are presented as follows: the view of stakeholder management and the model of global corporate citizenship, respectively. While there are relevant differences in these, they share important common ground.

StakeholderAny person, group, or organization affected by an organization’s actions. For businesses, it can include owners and investors, employees, customers, suppliers, and all members of society affected by the organization. engagement is a formal process of relationship management through which companies or industries engage with a set of their stakeholders in an effort to align and advance their mutual interests. This often involves different stakeholders, such as owners, employees and customers, identifying what is in their collective interest. For example, for BP in the future to practice more effective forms of environmental risk management and for Google to invest in renewable energy innovation.

Corporate citizenship involves corporate management focusing on the net contribution that a company makes through its core business activities, its social investment and philanthropy programs, and its engagement in public policy to society and a broad set of stakeholders. That contribution is determined by the manner in which a company manages its economic, social and environmental impacts and manages its relationships with different stakeholders, in particular shareholders, employees, customers, business partners, governments, communities and future generations.

The relationship of the models of corporate social responsibility to sustainability is reflected in the values statement of Johnson & Johnson, a company with a strong reputation for corporate citizenship. (Note the “corporate citizenship, or sustainability.”)

We see corporate citizenship, or sustainability, not as a set of “add-ons” to our business but rather as intrinsic to everything we do. We’ve long recognized that the sustainability of our business depends on being attuned to society’s expectations across many domains—including the environment, access to medicines, advocacy, governance and compliance."Sustainability Report 2008,” Johnson & Johnson, http://www.jnj.com/wps/wcm/connect/ad9170804f55661a9ec3be1bb31559c7/2008+Sustainability+Report.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

CSR covers the responsibilities corporations have to a broad set of stakeholders, including the communities within which they are based and operate. More specifically, CSR for many management scholars involves a business identifying its key stakeholder groups and incorporating their needs and values within the business’s strategic, day-to-day decision-making process.M. Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (University of Chicago Press, 1962). The stakeholders in corporations and any private company include owners and investors, employees, consumers, and all those affected by the actions of the corporation.

A key stakeholder group relevant to sustainable business practices is consumers. The environmental movement in the United States was ignited in the 1970s as an increasing percentage of consumers began to understand that the environment was at risk. Information about this was enhanced with the 1972 publication of Limits to Growth, a research study by the MIT Systems Lab and released by the Club of Rome. The book explained the results of computer models that predicted when the world would run out of certain resources. The study presented what was for many at the time a novel finding that the earth’s resources were finite.

Thirty years after the Limits of Growth was published, public interest and concern for the environment was raised to another level with the emergence of increased scientific evidence of global warming and the human contribution to global warming and the presentation to the general public of the evidence by former US vice president Al Gore in the 2006 movie An Inconvenient Truth. The release of the movie was at the same time as the George W. Bush administration was resisting pressure to move forward on federal policy to address global warming (see Chapter 2 "The Science of Sustainability" and Chapter 3 "Government, Public Policy, and Sustainable Business").

Increasing numbers of people in the United States and elsewhere turned to business as both the problem and the solution to global warming. Research findings had heightened recognition of businesses as major users of societal resources and major contributors to environmental problems. And with that, there was increased pressure on businesses to be part of the solution to global warming.

Consumers played a very significant role in raising businesses’ interest in sustainability. Consumers can use the market (i.e., their purchases) to send a signal to businesses about their concern for the environment and sustainability. Each and every consumer’s decision to purchase or not purchase from a company based on the business entities’ environmental or sustainability practices directly impacts a company’s bottom line. In this way, consumers can be, and increasingly are, a very powerful external force that can motivate companies to become more sustainable in their practices (see Chapter 6 "Sustainable Business Marketing").

The power of consumers and also the opportunity for corporations to influence consumer demand to benefit their sales is reflected in the corporate statement of Green Mountain Coffee as follows (see Chapter 9 "Case: Brewing a Better World: Sustainable Supply Chain Management at Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, Inc."):

We’re focusing on building demand for sustainable products and evolving our product line to be more sustainable. Once consumers understand the goals of Fair Trade and sustainability—protecting scarce resources, strengthening communities, reducing poverty, and ensuring equity in commercial relationships—they will want to help build a better world.

A new group of environmentally responsible consumers has emerged. They are the lead adopters and others are following. These consumers take into account a variety of factors before they choose to support a company by buying their product. They consider the impact of materials and processes used to manufacture and package goods, how products are distributed and disposed of, a company’s broader corporate philosophy on the environment, and even a company’s support of public environmental education programs. These factors, among many others, are becoming increasingly important to consumers and consequently to the companies themselves.

According to a 2006 Mintel Research study, the so-called green marketplace was estimated at somewhere between $300 billion to $500 billion a year. And all indications are that it has grown significantly since then. The same study showed that there were approximately thirty-five million Americans who regularly bought green products and that 77 percent of consumers changed their purchasing habits due to a company’s green image. Marketing statistics from many different industries support this. Green homes, for example, are estimated to cost between 2 percent to 5 percent more to construct but are valued at 10 percent to 15 percent more in the marketplace. Likewise, organic dairy products are priced typically 15 percent to 20 percent more than conventional ones, and organic meats are often priced two to three times more than traditional meat.Jay Hasbrouck and Allison Woodruff, “Green Homeowners as Lead Adopters,” Intel Technology Journal 12, no. 1 (2008): 42.

Many companies that have already incorporated sustainability into their business have received benefits in the form of reduced energy and other costs, increased consumer demand, and improved market share. But despite the growing trend of “green purchasing,” approximately one-quarter of Americans still do not consciously purchase goods based on a company’s sustainability efforts. There is an even larger segment of Americans (approximately 50 percent) that express some level of concern for the environment but may not have the knowledge or commitment required to purchase goods based on a business’s efforts in sustainability.

Environmental organizations have responded to this lack of information by providing consumers with resources to make environmentally responsible buying decisions. For example, Climate Counts (http://www.climatecounts.org/scorecard_overview.php) is a nonprofit organization that evaluates, with numerical scores, more than 140 major corporations on their efforts to reverse climate change. Climate Counts publishes these scores so that consumers may use them to support those companies that are showing serious commitment to the environment. The companies are scored on a scale from zero to one hundred based on twenty-two criteria to determine whether a company has

- measured its climate impact,

- reduced its impact on climate change,

- supported (or blocked) progressive climate legislation,

- publicly disclosed its climate actions in a clear and comprehensive format.

In Climate Counts’s Winter/Spring 2010 edition of their scorecard, scores ranged from zero to a high of eighty-three. Climate Counts works extensively to educate consumers on corporate sustainability and to encourage them to support companies with scores as close to one hundred as possible.

While Climate Counts focuses on larger corporations, organizations such as the Green Alliance in New Hampshire (http://www.greenalliance.biz) address local companies and their efforts to incorporate sustainability into their business. Based in the Seacoast region of New Hampshire, Green Alliance represents one of the many organizations that spur environmentally responsible purchasing on a local level. Similar to Climate Counts, Green Alliance scores companies to direct consumers to the most sustainable buying options. Similar types of organizations are located in communities across the country and have affected the sustainable business practices of private companies.

Apart from the stakeholder-driven perspective of CSR, another important concept of CSR is the notion of companies looking beyond profits to their role in society. It refers to a company linking itself with ethical values, transparency, employee relations, compliance with legal requirements, and overall respect for the communities in which they operate. With this perspective, CSR moves closer to the sustainable business perspective, as the focus includes managing the impact businesses have on the environment and society.

A path for businesses to adopt sustainable business practices might be thought of as a continuum (see as follows).

- It can start with Friedman’s perspective that businesses adopt sustainable practices because it is a legal obligation—governmental laws and regulations require it.

- It can include, also from Friedman, the pure profit-driven motive—businesses adopt sustainable practices because they clearly contribute to corporate profits; for example, it can contribute to brand name recognition and sales. With this motive there is little systematic search for opportunities or embedding of sustainable practices in business.

- It can include a balanced values-based approach in which businesses adopt sustainable business practices from a search for a balanced solution to optimize economic performance and societal benefits.

- It can include a systems approach. Sustainable business practices are fully embedded into every aspect of the business. Businesses have an understanding of the interconnectivity of their business to society over time and act on it. The focus is on the sustainability of all critical aspects of the system and the influence of the private company on these elements. Business sustainability is valued along with sustainability of environmental, social, and human resource elements in the system.

Key Takeaways

- There are many views of the corporation and private companies and their role or place in a private market economy.

- For economist Milton Friedman, there is one and only one social responsibility of business beyond adhering to society’s laws and that is to use its resources and engage in activities to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game.

- Others view the social responsibility of business to include concern for various stakeholders and for the morality and ethics of their practices and their impact on stakeholders.

- For businesses looking to become more sustainable, it can be thought of as a continuum between legal and ethical actions up to a systems perspective.

Exercises

- Do you agree with Milton Friedman’s profit-driven philosophy that the purpose of business is to earn a profit and that should be the sole focus of business, with government being responsible for social and environmental issues? Why or why not?

- Search the web for an article that provides an example of a business that implemented a social or environmental practice that had negative economic impact on the company. Search the web for an article that provides an example of the business that implemented a social environment of practice that had a positive economic impact on the company. Why do you feel the company with a practice that has a negative impact on the company experienced that result? Based on these two articles, do you think that companies should be concerned with sustainability?

- It can be challenging to think of operating a business with a systems perspective. Think of one example of a sustainability practice that incorporates elements of a systems perspective. Describe the internal and external environment and the linkages between the two and what healthy practices meet the criteria of being considered sustainable.

1.6 A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Business Practice

Learning Objectives

- Explain how sustainable business practice can be a source of competitive advantage for businesses.

- Understand what it means for a business to create shared value.

- Describe how it can be beneficial for society to have businesses acting to address sustainability concerns.

A useful prospective for sustainable business practitioners will be between the balanced values approach and the systems approach. It would use a systems approach, but it would focus on the system from the inside of the business perspective and focus on the business interaction with the external environment.

But how can this systems perspective be incorporated into real-life business practices? The most useful business guidance can be drawn from arguably the most prominent scholar of corporate strategy, Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter. Porter’s strategic corporate social responsibility (CSR) model can be applied to sustainability. He rejects the pure stakeholder approachA management approach that takes into account the views of all the stakeholders of the business and not just the owners. The goal of this approach is to provide products or services that better meet customer needs and also prove the corporate citizenship of the company. to CSR because stakeholder groups, he believes, can never fully understand a corporation’s capabilities, competitive positioning, or trade-offs it must make and because the loudness of the stakeholder voice does not necessarily signify the importance of an issue—either to the company or to the world. The stakeholder approach, for Porter, is too often used to placate interests or public relations with minimal value to society and to the company. Greenwashing is an example of this, and it has proven to be a failed approach.

Porter’s point about CSR that can be applied to sustainability is that sustainable business practices can be much more than a cost, a good deed, or good public relations for businesses—it can be a source of competitive advantage. In his 2006 article with Mark R Kramer, “Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility,” Porter proposes a new way to look at the relationship between business and society that does not treat corporate profits and societal well-being (including sustainability) as just a balancing exercise. The authors introduce a framework that individual companies can use to identify the social consequences of their actions, to discover opportunities to benefit society and themselves by strengthening the competitive context in which they operate, to determine which CSR or sustainability initiatives they should address, and to find the most effective ways of doing so.

Perceiving social responsibilities, such as acting with attention to sustainability, as an opportunity rather than as damage control or a public relations campaign requires for most private companies to dramatically shift their thinking to a mind-set, the authors argue, that will become increasingly important to competitive success. The principle of sustainability appealing to company’s enlightened self-interest works best for issues that coincide with a company’s economic interests and when the company has strategically assessed what actions to address. The example of McDonald’s using less packaging that reduces company materials and disposal costs at the same time that it helps the environment illustrates this.

Another example is GE and Jack Welch, the famous former CEO of GE. While he was CEO at GE, Jack Welch was often referred to as the greatest CEO of the last century. G. Michael Maddock highlights that “for all the accolades Welch received, those handing out plaudits missed a huge one: He was the King of Green. Six SigmaA business management strategy that seeks to improve the quality of business processes by reducing the causes of defects in reducing variability. The strategy was developed by Motorola in 1981 and relies on quality management and statistical methods. The strategy is most commonly seen in manufacturing environments., the management style (and manufacturing process) he championed, is all about getting leaner: reducing steps, costs, and materials. And lean is green.”G. Maddock, “Going Green’s Unexpected Advantage,” BusinessWeek, February 2, 2010, http://www.businessweek.com/managing/content/feb2010/ca2010021_587893.htm. Lean manufacturing benefited GE, in particular its competitive position, by reducing the company’s costs of manufacturing and operations relative to competitors while providing broader societal benefits.

A few corporations such as Stonyfield Farms (Chapter 13 "Case: Strategic Mission–Driven Sustainable Business: Stonyfield Yogurt") stand out even more than McDonald’s and GE with their exceptional long-term commitment to sustainability. Gary Hirshberg, who refers to himself as the CE-Yo of Stonyfield in his book Stirring It Up: How to Make Money and Save the World, highlights how the company has built its entire value proposition around social issues with a focus on environmental actions.Gary Hirshberg, Stirring It Up: How to Make Money and Save the World (New York: Hyperion Books, 2008).

Sidebar

An Example of a Company Value Proposition Driven by Sustainability Objective

Stonyfield Farms value proposition is to sell organic, natural, and healthy food products to customers who care about food quality and the environment.

© Thinkstock

What Can Companies Do to Deepen Engagement on Sustainability?

Porter and Kramer suggest that companies do the following:

- First, identify their environmental impact (e.g., contribution to carbon emissions).

- Then determine which impact(s) they can benefit the most from addressing.

- Then determine the most effective ways to do so.

For the economy and society overall, businesses’ attention to sustainability has already become a source of social progress, as businesses apply considerable attention and resources to reduce their environmental footprint, which benefits their bottom line and also benefits the environment and society more broadly. But most companies are only at the initial stages of the sustainability learning curve.

Sidebar

Competitive Advantage

When a firm sustains profits that exceed the average for its industry, the firm is said to possess a competitive advantage over its rivals. The goal of much of business strategy is to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. Michael Porter identified two basic types of competitive advantage. The first is when the firm is able to deliver the same benefits as competitors but at a lower cost (cost advantage). The second is when a firm can deliver benefits that exceed those of competing products (differentiation advantage). Thus a competitive advantage enables the firm to create superior value for its customers and superior profits for itself.Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York: Free Press, 1985).

What Porter and Kramer suggest is not easy. To enhance sustainable business practices, it must be rooted in an understanding of the interrelations between a corporation and society while at the same time anchored in the activities and strategies of specific companies. No business and no single industry can solve all of society’s environmental problems; instead each company can work on environmental issues that intersect with its particular business.

What should guide each and every sustainable business practice is whether it presents an opportunity to create shared value—that it provides a meaningful benefit to society and that it is also valuable to the business. Each company will have to sort through their own sustainability issues and rank them in terms of potential impact. For example, for Toyota, a focus on fuel efficiency with the development and promotion of the highly fuel efficient hybrid vehicle the Prius provided environmental benefits and has been a source of competitive advantage for the company helping it to increase sales and profits. The same is true of Stonyfield and its focus on providing preservative-free, healthy, organic yogurt produced with manufacturing processes that minimize material and energy use.