This is “Rhetorical Modes”, chapter 10 from the book Successful Writing (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 10 Rhetorical Modes

10.1 Narration

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of narrative writing.

- Understand how to write a narrative essay.

Rhetorical modesThe ways in which we can effectively communicate through language. simply mean the ways in which we can effectively communicate through language. This chapter covers nine common rhetorical modes. As you read about these nine modes, keep in mind that the rhetorical mode a writer chooses depends on his or her purpose for writing. Sometimes writers incorporate a variety of modes in any one essay. In covering the nine modes, this chapter also emphasizes the rhetorical modes as a set of tools that will allow you greater flexibility and effectiveness in communicating with your audience and expressing your ideas.

The Purpose of Narrative Writing

Narration means the art of storytelling, and the purpose of narrative writingThe art of telling stories. is to tell stories. Any time you tell a story to a friend or family member about an event or incident in your day, you engage in a form of narration. In addition, a narrative can be factual or fictional. A factual storyA story based on—and faithful to—actual events as they happened in real life. is one that is based on, and tries to be faithful to, actual events as they unfolded in real life. A fictional storyA made-up, or imagined, story. is a made-up, or imagined, story; the writer of a fictional story can create characters and events as he or she sees fit.

The big distinction between factual and fictional narratives is based on a writer’s purpose. The writers of factual stories try to recount events as they actually happened, but writers of fictional stories can depart from real people and events because the writers’ intents are not to retell a real-life event. Biographies and memoirs are examples of factual stories, whereas novels and short stories are examples of fictional stories.

Tip

Because the line between fact and fiction can often blur, it is helpful to understand what your purpose is from the beginning. Is it important that you recount history, either your own or someone else’s? Or does your interest lie in reshaping the world in your own image—either how you would like to see it or how you imagine it could be? Your answers will go a long way in shaping the stories you tell.

Ultimately, whether the story is fact or fiction, narrative writing tries to relay a series of events in an emotionally engaging way. You want your audience to be moved by your story, which could mean through laughter, sympathy, fear, anger, and so on. The more clearly you tell your story, the more emotionally engaged your audience is likely to be.

Exercise 1

On a separate sheet of paper, start brainstorming ideas for a narrative. First, decide whether you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then, freewrite for five minutes. Be sure to use all five minutes, and keep writing the entire time. Do not stop and think about what to write.

The following are some topics to consider as you get going:

- Childhood

- School

- Adventure

- Work

- Love

- Family

- Friends

- Vacation

- Nature

- Space

The Structure of a Narrative Essay

Major narrative events are most often conveyed in chronological orderA method of organization that arranges ideas according to time., the order in which events unfold from first to last. Stories typically have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and these events are typically organized by time. Certain transitional words and phrases aid in keeping the reader oriented in the sequencing of a story. Some of these phrases are listed in Table 10.1 "Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time". For more information about chronological order, see Chapter 8 "The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?" and Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish".

Table 10.1 Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time

| after/afterward | as soon as | at last | before |

| currently | during | eventually | meanwhile |

| next | now | since | soon |

| finally | later | still | then |

| until | when/whenever | while | first, second, third |

The following are the other basic components of a narrative:

- PlotThe events as they unfold in sequence.. The events as they unfold in sequence.

- CharactersThe people who inhabit the story and move it forward.. The people who inhabit the story and move it forward. Typically, there are minor characters and main characters. The minor characters generally play supporting roles to the main character, or the protagonistThe main character of a narrative..

- ConflictThe primary problem or obstacle that unfolds in the plot that the protagonist must resolve.. The primary problem or obstacle that unfolds in the plot that the protagonist must solve or overcome by the end of the narrative. The way in which the protagonist resolves the conflict of the plot results in the theme of the narrative.

- ThemeThe ultimate message a narrative is trying to express; it can be either explicit or implicit.. The ultimate message the narrative is trying to express; it can be either explicit or implicit.

Writing at Work

When interviewing candidates for jobs, employers often ask about conflicts or problems a potential employee has had to overcome. They are asking for a compelling personal narrative. To prepare for this question in a job interview, write out a scenario using the narrative mode structure. This will allow you to troubleshoot rough spots, as well as better understand your own personal history. Both processes will make your story better and your self-presentation better, too.

Exercise 2

Take your freewriting exercise from the last section and start crafting it chronologically into a rough plot summary. To read more about a summary, see Chapter 6 "Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content". Be sure to use the time transition words and phrases listed in Table 10.1 "Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time" to sequence the events.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your rough plot summary.

Writing a Narrative Essay

When writing a narrative essay, start by asking yourself if you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then freewrite about topics that are of general interest to you. For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 "The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?".

Once you have a general idea of what you will be writing about, you should sketch out the major events of the story that will compose your plot. Typically, these events will be revealed chronologically and climax at a central conflict that must be resolved by the end of the story. The use of strong details is crucial as you describe the events and characters in your narrative. You want the reader to emotionally engage with the world that you create in writing.

Tip

To create strong details, keep the human senses in mind. You want your reader to be immersed in the world that you create, so focus on details related to sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch as you describe people, places, and events in your narrative.

As always, it is important to start with a strong introduction to hook your reader into wanting to read more. Try opening the essay with an event that is interesting to introduce the story and get it going. Finally, your conclusion should help resolve the central conflict of the story and impress upon your reader the ultimate theme of the piece. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample narrative essay.

Exercise 3

On a separate sheet of paper, add two or three paragraphs to the plot summary you started in the last section. Describe in detail the main character and the setting of the first scene. Try to use all five senses in your descriptions.

Key Takeaways

- Narration is the art of storytelling.

- Narratives can be either factual or fictional. In either case, narratives should emotionally engage the reader.

- Most narratives are composed of major events sequenced in chronological order.

- Time transition words and phrases are used to orient the reader in the sequence of a narrative.

- The four basic components to all narratives are plot, character, conflict, and theme.

- The use of sensory details is crucial to emotionally engaging the reader.

- A strong introduction is important to hook the reader. A strong conclusion should add resolution to the conflict and evoke the narrative’s theme.

10.2 Illustration

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of the illustration essay.

- Understand how to write an illustration essay.

The Purpose of Illustration in Writing

To illustrate means to show or demonstrate something clearly. An effective illustration essayAn essay that clearly demonstrates and supports a point through the use of evidence. clearly demonstrates and supports a point through the use of evidence.

As you learned in Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish", the controlling idea of an essay is called a thesisA sentence that presents the controlling idea of an essay. A thesis statement is often one sentence long, and it states the writer’s point of view.. A writer can use different types of evidence to support his or her thesis. Using scientific studies, experts in a particular field, statistics, historical events, current events, analogies, and personal anecdotes are all ways in which a writer can illustrate a thesis. Ultimately, you want the evidence to help the reader “see” your point, as one would see a good illustration in a magazine or on a website. The stronger your evidence is, the more clearly the reader will consider your point.

Using evidence effectively can be challenging, though. The evidence you choose will usually depend on your subject and who your reader is (your audience). When writing an illustration essay, keep in mind the following:

- Use evidence that is appropriate to your topic as well as appropriate for your audience.

- Assess how much evidence you need to adequately explain your point depending on the complexity of the subject and the knowledge of your audience regarding that subject.

For example, if you were writing about a new communication software and your audience was a group of English-major undergrads, you might want to use an analogy or a personal story to illustrate how the software worked. You might also choose to add a few more pieces of evidence to make sure the audience understands your point. However, if you were writing about the same subject and you audience members were information technology (IT) specialists, you would likely use more technical evidence because they would be familiar with the subject.

Keeping in mind your subject in relation to your audience will increase your chances of effectively illustrating your point.

Tip

You never want to insult your readers’ intelligence by overexplaining concepts the audience members may already be familiar with, but it may be necessary to clearly articulate your point. When in doubt, add an extra example to illustrate your idea.

Exercise 1

On a separate piece of paper, form a thesis based on each of the following three topics. Then list the types of evidence that would best explain your point for each of the two audiences.

-

Topic: Combat and mental health

Audience: family members of veterans, doctors

-

Topic: Video games and teen violence

Audience: parents, children

-

Topic: Architecture and earthquakes

Audience: engineers, local townspeople

The Structure of an Illustration Essay

The controlling idea, or thesis, belongs at the beginning of the essay. Evidence is then presented in the essay’s body paragraphs to support the thesis. You can start supporting your main point with your strongest evidence first, or you can start with evidence of lesser importance and have the essay build to increasingly stronger evidence. This type of organization—order of importanceA method of organization that arranges ideas according to their significance.—you learned about in Chapter 8 "The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?" and Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish".

The time transition words listed in Table 10.1 "Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time" are also helpful in ordering the presentation of evidence. Words like first, second, third, currently, next, and finally all help orient the reader and sequence evidence clearly. Because an illustration essay uses so many examples, it is also helpful to have a list of words and phrases to present each piece of evidence. Table 10.2 "Phrases of Illustration" provides a list of phrases for illustration.

Table 10.2 Phrases of Illustration

| case in point | for example |

| for instance | in particular |

| in this case | one example/another example |

| specifically | to illustrate |

Tip

Vary the phrases of illustration you use. Do not rely on just one. Variety in choice of words and phrasing is critical when trying to keep readers engaged in your writing and your ideas.

Writing at Work

In the workplace, it is often helpful to keep the phrases of illustration in mind as a way to incorporate them whenever you can. Whether you are writing out directives that colleagues will have to follow or requesting a new product or service from another company, making a conscious effort to incorporate a phrase of illustration will force you to provide examples of what you mean.

Exercise 2

On a separate sheet of paper, form a thesis based on one of the following topics. Then support that thesis with three pieces of evidence. Make sure to use a different phrase of illustration to introduce each piece of evidence you choose.

- Cooking

- Baseball

- Work hours

- Exercise

- Traffic

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers. Discuss which topic you like the best or would like to learn more about. Indicate which thesis statement you perceive as the most effective.

Writing an Illustration Essay

First, decide on a topic that you feel interested in writing about. Then create an interesting introduction to engage the reader. The main point, or thesis, should be stated at the end of the introduction.

Gather evidence that is appropriate to both your subject and your audience. You can order the evidence in terms of importance, either from least important to most important or from most important to least important. Be sure to fully explain all of your examples using strong, clear supporting details. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample illustration essay.

Exercise 3

On a separate sheet of paper, write a five-paragraph illustration essay. You can choose one of the topics from Note 10.23 "Exercise 1" or Note 10.27 "Exercise 2", or you can choose your own.

Key Takeaways

- An illustration essay clearly explains a main point using evidence.

- When choosing evidence, always gauge whether the evidence is appropriate for the subject as well as the audience.

- Organize the evidence in terms of importance, either from least important to most important or from most important to least important.

- Use time transitions to order evidence.

- Use phrases of illustration to call out examples.

10.3 Description

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of the description essay.

- Understand how to write a description essay.

The Purpose of Description in Writing

Writers use description in writing to make sure that their audience is fully immersed in the words on the page. This requires a concerted effort by the writer to describe his or her world through the use of sensory details.

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, sensory detailsDescriptions that appeal to our sense of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. are descriptions that appeal to our sense of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. Your descriptions should try to focus on the five senses because we all rely on these senses to experience the world. The use of sensory details, then, provides you the greatest possibility of relating to your audience and thus engaging them in your writing, making descriptive writing important not only during your education but also during everyday situations.

Tip

Avoid empty descriptors if possible. Empty descriptors are adjectives that can mean different things to different people. Good, beautiful, terrific, and nice are examples. The use of such words in descriptions can lead to misreads and confusion. A good day, for instance, can mean far different things depending on one’s age, personality, or tastes.

Writing at Work

Whether you are presenting a new product or service to a client, training new employees, or brainstorming ideas with colleagues, the use of clear, evocative detail is crucial. Make an effort to use details that express your thoughts in a way that will register with others. Sharp, concise details are always impressive.

Exercise 1

On a separate sheet of paper, describe the following five items in a short paragraph. Use at least three of the five senses for each description.

- Night

- Beach

- City

- Dinner

- Stranger

The Structure of a Description Essay

Description essaysEssays that typically describe a person, a place, or an object using sensory details. typically describe a person, a place, or an object using sensory details. The structure of a descriptive essay is more flexible than in some of the other rhetorical modes. The introduction of a description essay should set up the tone and point of the essay. The thesis should convey the writer’s overall impression of the person, place, or object described in the body paragraphs.

The organization of the essay may best follow spatial orderA method of organization that arranges ideas according to physical characteristics or appearance., an arrangement of ideas according to physical characteristics or appearance. Depending on what the writer describes, the organization could move from top to bottom, left to right, near to far, warm to cold, frightening to inviting, and so on.

For example, if the subject were a client’s kitchen in the midst of renovation, you might start at one side of the room and move slowly across to the other end, describing appliances, cabinetry, and so on. Or you might choose to start with older remnants of the kitchen and progress to the new installations. Maybe start with the floor and move up toward the ceiling.

Exercise 2

On a separate sheet of paper, choose an organizing strategy and then execute it in a short paragraph for three of the following six items:

- Train station

- Your office

- Your car

- A coffee shop

- Lobby of a movie theater

-

Mystery Option*

*Choose an object to describe but do not indicate it. Describe it, but preserve the mystery.

Writing a Description Essay

Choosing a subject is the first step in writing a description essay. Once you have chosen the person, place, or object you want to describe, your challenge is to write an effective thesis statement to guide your essay.

The remainder of your essay describes your subject in a way that best expresses your thesis. Remember, you should have a strong sense of how you will organize your essay. Choose a strategy and stick to it.

Every part of your essay should use vivid sensory details. The more you can appeal to your readers’ senses, the more they will be engaged in your essay. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample description essay.

Exercise 3

On a separate sheet of paper, choose one of the topics that you started in Note 10.37 "Exercise 2", and expand it into a five-paragraph essay. Expanding on ideas in greater detail can be difficult. Sometimes it is helpful to look closely at each of the sentences in a summary paragraph. Those sentences can often serve as topic sentences to larger paragraphs.

Mystery Option: Here is an opportunity to collaborate. Please share with a classmate and compare your thoughts on the mystery descriptions. Did your classmate correctly guess your mystery topic? If not, how could you provide more detail to describe it and lead them to the correct conclusion?

Key Takeaways

- Description essays should describe something vividly to the reader using strong sensory details.

- Sensory details appeal to the five human senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch.

- A description essay should start with the writer’s main impression of a person, a place, or an object.

- Use spatial order to organize your descriptive writing.

10.4 Classification

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of the classification essay.

- Understand how to write a classification essay.

The Purpose of Classification in Writing

The purpose of classificationTo break down a subject into smaller, more manageable, more specific parts. is to break down broad subjects into smaller, more manageable, more specific parts. We classify things in our daily lives all the time, often without even thinking about it. Cell phones, for example, have now become part of a broad category. They can be classified as feature phones, media phones, and smartphones.

Smaller categories, and the way in which these categories are created, help us make sense of the world. Keep both of these elements in mind when writing a classification essay.

Tip

Choose topics that you know well when writing classification essays. The more you know about a topic, the more you can break it into smaller, more interesting parts. Adding interest and insight will enhance your classification essays.

Exercise 1

On a separate sheet of paper, break the following categories into smaller classifications.

- The United States

- Colleges and universities

- Beverages

- Fashion

The Structure of a Classification Essay

The classification essay opens with an introductory paragraph that introduces the broader topic. The thesis should then explain how that topic is divided into subgroups and why. Take the following introductory paragraph, for example:

When people think of New York, they often think of only New York City. But New York is actually a diverse state with a full range of activities to do, sights to see, and cultures to explore. In order to better understand the diversity of New York state, it is helpful to break it into these five separate regions: Long Island, New York City, Western New York, Central New York, and Northern New York.

The underlined thesis explains not only the category and subcategory but also the rationale for breaking it into those categories. Through this classification essay, the writer hopes to show his or her readers a different way of considering the state.

Each body paragraph of a classification essay is dedicated to fully illustrating each of the subcategories. In the previous example, then, each region of New York would have its own paragraph.

The conclusion should bring all the categories and subcategories back together again to show the reader the big picture. In the previous example, the conclusion might explain how the various sights and activities of each region of New York add to its diversity and complexity.

Tip

To avoid settling for an overly simplistic classification, make sure you break down any given topic at least three different ways. This will help you think outside the box and perhaps even learn something entirely new about a subject.

Exercise 2

Using your classifications from Note 10.43 "Exercise 1", write a brief paragraph explaining why you chose to organize each main category in the way that you did.

Writing a Classification Essay

Start with an engaging opening that will adequately introduce the general topic that you will be dividing into smaller subcategories. Your thesis should come at the end of your introduction. It should include the topic, your subtopics, and the reason you are choosing to break down the topic in the way that you are. Use the following classification thesis equation:

topic + subtopics + rationale for the subtopics = thesis.The organizing strategy of a classification essay is dictated by the initial topic and the subsequent subtopics. Each body paragraph is dedicated to fully illustrating each of the subtopics. In a way, coming up with a strong topic pays double rewards in a classification essay. Not only do you have a good topic, but you also have a solid organizational structure within which to write.

Be sure you use strong details and explanations for each subcategory paragraph that help explain and support your thesis. Also, be sure to give examples to illustrate your points. Finally, write a conclusion that links all the subgroups together again. The conclusion should successfully wrap up your essay by connecting it to your topic initially discussed in the introduction. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample classification essay.

Exercise 3

Building on Note 10.43 "Exercise 1" and Note 10.46 "Exercise 2", write a five-paragraph classification essay about one of the four original topics. In your thesis, make sure to include the topic, subtopics, and rationale for your breakdown. And make sure that your essay is organized into paragraphs that each describes a subtopic.

Key Takeaways

- The purpose of classification is to break a subject into smaller, more manageable, more specific parts.

- Smaller subcategories help us make sense of the world, and the way in which these subcategories are created also helps us make sense of the world.

- A classification essay is organized by its subcategories.

10.5 Process Analysis

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of the process analysis essay.

- Understand how to write a process analysis essay.

The Purpose of Process Analysis in Writing

The purpose of a process analysis essayAn essay that explains how to do something, how something works, or both. is to explain how to do something or how something works. In either case, the formula for a process analysis essay remains the same. The process is articulated into clear, definitive steps.

Almost everything we do involves following a step-by-step process. From riding a bike as children to learning various jobs as adults, we initially needed instructions to effectively execute the task. Likewise, we have likely had to instruct others, so we know how important good directions are—and how frustrating it is when they are poorly put together.

Writing at Work

The next time you have to explain a process to someone at work, be mindful of how clearly you articulate each step. Strong communication skills are critical for workplace satisfaction and advancement. Effective process analysis plays a critical role in developing that skill set.

Exercise 1

On a separate sheet of paper, make a bulleted list of all the steps that you feel would be required to clearly illustrate three of the following four processes:

- Tying a shoelace

- Parallel parking

- Planning a successful first date

- Being an effective communicator

The Structure of a Process Analysis Essay

The process analysis essay opens with a discussion of the process and a thesis statement that states the goal of the process.

The organization of a process analysis essay typically follows chronological order. The steps of the process are conveyed in the order in which they usually occur. Body paragraphs will be constructed based on these steps. If a particular step is complicated and needs a lot of explaining, then it will likely take up a paragraph on its own. But if a series of simple steps is easier to understand, then the steps can be grouped into a single paragraph.

The time transition phrases covered in the Narration and Illustration sections are also helpful in organizing process analysis essays (see Table 10.1 "Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time" and Table 10.2 "Phrases of Illustration"). Words such as first, second, third, next, and finally are helpful cues to orient reader and organize the content of essay.

Tip

Always have someone else read your process analysis to make sure it makes sense. Once we get too close to a subject, it is difficult to determine how clearly an idea is coming across. Having a friend or coworker read it over will serve as a good way to troubleshoot any confusing spots.

Exercise 2

Choose two of the lists you created in Note 10.52 "Exercise 1" and start writing out the processes in paragraph form. Try to construct paragraphs based on the complexity of each step. For complicated steps, dedicate an entire paragraph. If less complicated steps fall in succession, group them into a single paragraph.

Writing a Process Analysis Essay

Choose a topic that is interesting, is relatively complex, and can be explained in a series of steps. As with other rhetorical writing modes, choose a process that you know well so that you can more easily describe the finer details about each step in the process. Your thesis statement should come at the end of your introduction, and it should state the final outcome of the process you are describing.

Body paragraphs are composed of the steps in the process. Each step should be expressed using strong details and clear examples. Use time transition phrases to help organize steps in the process and to orient readers. The conclusion should thoroughly describe the result of the process described in the body paragraphs. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read an example of a process analysis essay.

Exercise 3

Choose one of the expanded lists from Note 10.54 "Exercise 2". Construct a full process analysis essay from the work you have already done. That means adding an engaging introduction, a clear thesis, time transition phrases, body paragraphs, and a solid conclusion.

Key Takeaways

- A process analysis essay explains how to do something, how something works, or both.

- The process analysis essay opens with a discussion of the process and a thesis statement that states the outcome of the process.

- The organization of a process analysis essay typically follows a chronological sequence.

- Time transition phrases are particularly helpful in process analysis essays to organize steps and orient reader.

10.6 Definition

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of the definition essay.

- Understand how to write a definition essay.

The Purpose of Definition in Writing

The purpose of a definition essay may seem self-explanatory: the purpose of the definition essay is to simply define something. But defining terms in writing is often more complicated than just consulting a dictionary. In fact, the way we define terms can have far-reaching consequences for individuals as well as collective groups.

Take, for example, a word like alcoholism. The way in which one defines alcoholism depends on its legal, moral, and medical contexts. Lawyers may define alcoholism in terms of its legality; parents may define alcoholism in terms of its morality; and doctors will define alcoholism in terms of symptoms and diagnostic criteria. Think also of terms that people tend to debate in our broader culture. How we define words, such as marriage and climate change, has enormous impact on policy decisions and even on daily decisions. Think about conversations couples may have in which words like commitment, respect, or love need clarification.

Defining terms within a relationship, or any other context, can at first be difficult, but once a definition is established between two people or a group of people, it is easier to have productive dialogues. Definitions, then, establish the way in which people communicate ideas. They set parameters for a given discourse, which is why they are so important.

Tip

When writing definition essays, avoid terms that are too simple, that lack complexity. Think in terms of concepts, such as hero, immigration, or loyalty, rather than physical objects. Definitions of concepts, rather than objects, are often fluid and contentious, making for a more effective definition essay.

Writing at Work

Definitions play a critical role in all workplace environments. Take the term sexual harassment, for example. Sexual harassment is broadly defined on the federal level, but each company may have additional criteria that define it further. Knowing how your workplace defines and treats all sexual harassment allegations is important. Think, too, about how your company defines lateness, productivity, or contributions.

Exercise 1

On a separate sheet of paper, write about a time in your own life in which the definition of a word, or the lack of a definition, caused an argument. Your term could be something as simple as the category of an all-star in sports or how to define a good movie. Or it could be something with higher stakes and wider impact, such as a political argument. Explain how the conversation began, how the argument hinged on the definition of the word, and how the incident was finally resolved.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your responses.

The Structure of a Definition Essay

The definition essay opens with a general discussion of the term to be defined. You then state as your thesis your definition of the term.

The rest of the essay should explain the rationale for your definition. Remember that a dictionary’s definition is limiting, and you should not rely strictly on the dictionary entry. Instead, consider the context in which you are using the word. ContextThe circumstances, conditions, or setting in which something exists or occurs. identifies the circumstances, conditions, or setting in which something exists or occurs. Often words take on different meanings depending on the context in which they are used. For example, the ideal leader in a battlefield setting could likely be very different than a leader in an elementary school setting. If a context is missing from the essay, the essay may be too short or the main points could be confusing or misunderstood.

The remainder of the essay should explain different aspects of the term’s definition. For example, if you were defining a good leader in an elementary classroom setting, you might define such a leader according to personality traits: patience, consistency, and flexibility. Each attribute would be explained in its own paragraph.

Tip

For definition essays, try to think of concepts that you have a personal stake in. You are more likely to write a more engaging definition essay if you are writing about an idea that has personal value and importance.

Writing at Work

It is a good idea to occasionally assess your role in the workplace. You can do this through the process of definition. Identify your role at work by defining not only the routine tasks but also those gray areas where your responsibilities might overlap with those of others. Coming up with a clear definition of roles and responsibilities can add value to your résumé and even increase productivity in the workplace.

Exercise 2

On a separate sheet of paper, define each of the following items in your own terms. If you can, establish a context for your definition.

- Bravery

- Adulthood

- Consumer culture

- Violence

- Art

Writing a Definition Essay

Choose a topic that will be complex enough to be discussed at length. Choosing a word or phrase of personal relevance often leads to a more interesting and engaging essay.

After you have chosen your word or phrase, start your essay with an introduction that establishes the relevancy of the term in the chosen specific context. Your thesis comes at the end of the introduction, and it should clearly state your definition of the term in the specific context. Establishing a functional context from the beginning will orient readers and minimize misunderstandings.

The body paragraphs should each be dedicated to explaining a different facet of your definition. Make sure to use clear examples and strong details to illustrate your points. Your concluding paragraph should pull together all the different elements of your definition to ultimately reinforce your thesis. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample definition essay.

Exercise 3

Create a full definition essay from one of the items you already defined in Note 10.64 "Exercise 2". Be sure to include an interesting introduction, a clear thesis, a well-explained context, distinct body paragraphs, and a conclusion that pulls everything together.

Key Takeaways

- Definitions establish the way in which people communicate ideas. They set parameters for a given discourse.

- Context affects the meaning and usage of words.

- The thesis of a definition essay should clearly state the writer’s definition of the term in the specific context.

- Body paragraphs should explain the various facets of the definition stated in the thesis.

- The conclusion should pull all the elements of the definition together at the end and reinforce the thesis.

10.7 Comparison and Contrast

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of comparison and contrast in writing.

- Explain organizational methods used when comparing and contrasting.

- Understand how to write a compare-and-contrast essay.

The Purpose of Comparison and Contrast in Writing

ComparisonIn writing, to discuss things that are similar in nature. in writing discusses elements that are similar, while contrastIn writing, to discuss things that are different. in writing discusses elements that are different. A compare-and-contrast essayAn essay that analyzes two subjects by either comparing them, contrasting them, or both., then, analyzes two subjects by comparing them, contrasting them, or both.

The key to a good compare-and-contrast essay is to choose two or more subjects that connect in a meaningful way. The purpose of conducting the comparison or contrast is not to state the obvious but rather to illuminate subtle differences or unexpected similarities. For example, if you wanted to focus on contrasting two subjects you would not pick apples and oranges; rather, you might choose to compare and contrast two types of oranges or two types of apples to highlight subtle differences. For example, Red Delicious apples are sweet, while Granny Smiths are tart and acidic. Drawing distinctions between elements in a similar category will increase the audience’s understanding of that category, which is the purpose of the compare-and-contrast essay.

Similarly, to focus on comparison, choose two subjects that seem at first to be unrelated. For a comparison essay, you likely would not choose two apples or two oranges because they share so many of the same properties already. Rather, you might try to compare how apples and oranges are quite similar. The more divergent the two subjects initially seem, the more interesting a comparison essay will be.

Writing at Work

Comparing and contrasting is also an evaluative tool. In order to make accurate evaluations about a given topic, you must first know the critical points of similarity and difference. Comparing and contrasting is a primary tool for many workplace assessments. You have likely compared and contrasted yourself to other colleagues. Employee advancements, pay raises, hiring, and firing are typically conducted using comparison and contrast. Comparison and contrast could be used to evaluate companies, departments, or individuals.

Exercise 1

Brainstorm an essay that leans toward contrast. Choose one of the following three categories. Pick two examples from each. Then come up with one similarity and three differences between the examples.

- Romantic comedies

- Internet search engines

- Cell phones

Exercise 2

Brainstorm an essay that leans toward comparison. Choose one of the following three items. Then come up with one difference and three similarities.

- Department stores and discount retail stores

- Fast food chains and fine dining restaurants

- Dogs and cats

The Structure of a Comparison and Contrast Essay

The compare-and-contrast essay starts with a thesis that clearly states the two subjects that are to be compared, contrasted, or both and the reason for doing so. The thesis could lean more toward comparing, contrasting, or both. Remember, the point of comparing and contrasting is to provide useful knowledge to the reader. Take the following thesis as an example that leans more toward contrasting.

Thesis statement: Organic vegetables may cost more than those that are conventionally grown, but when put to the test, they are definitely worth every extra penny.

Here the thesis sets up the two subjects to be compared and contrasted (organic versus conventional vegetables), and it makes a claim about the results that might prove useful to the reader.

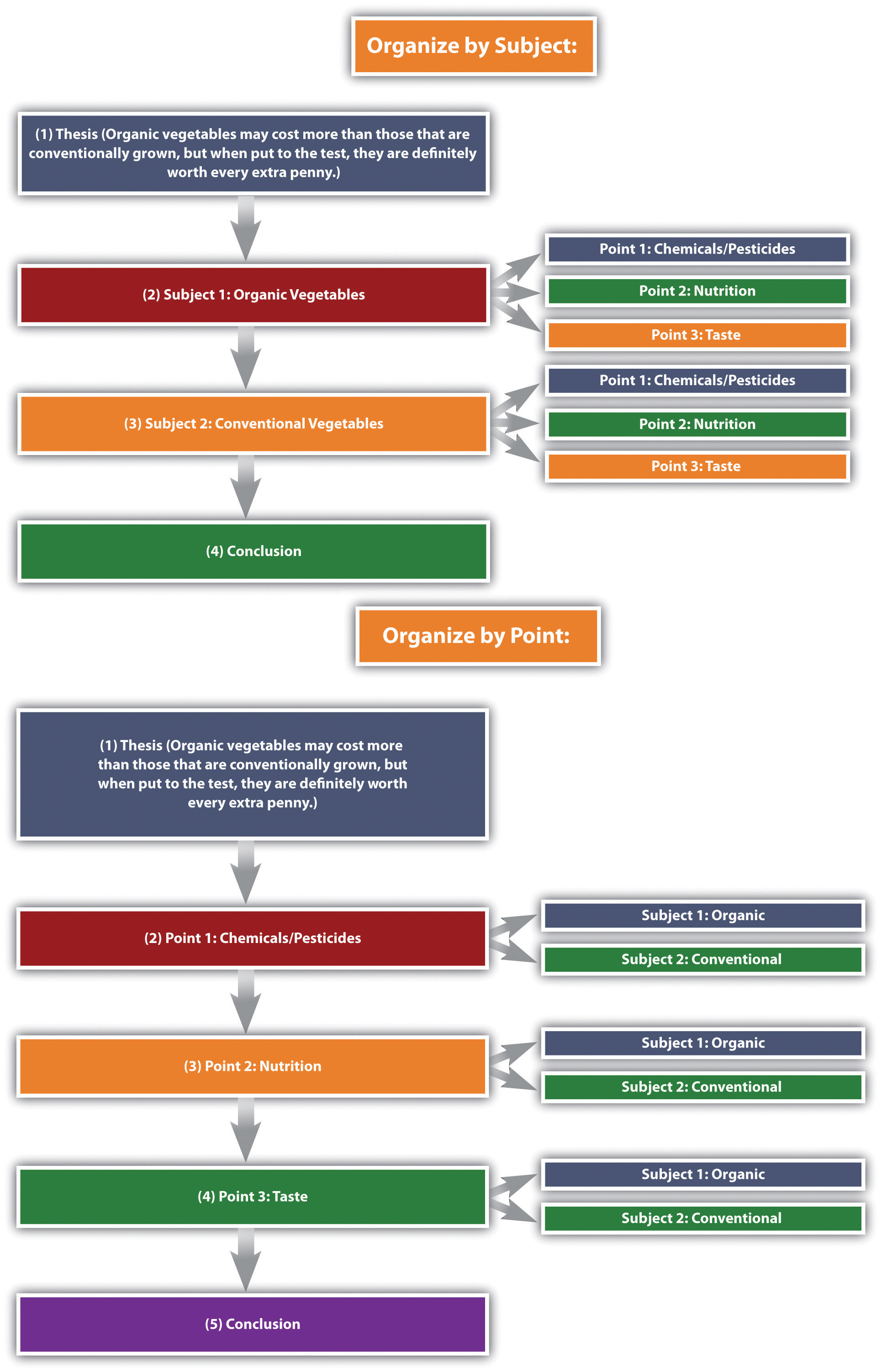

You may organize compare-and-contrast essays in one of the following two ways:

- According to the subjects themselves, discussing one then the other

- According to individual points, discussing each subject in relation to each point

See Figure 10.1 "Comparison and Contrast Diagram", which diagrams the ways to organize our organic versus conventional vegetables thesis.

Figure 10.1 Comparison and Contrast Diagram

The organizational structure you choose depends on the nature of the topic, your purpose, and your audience.

Given that compare-and-contrast essays analyze the relationship between two subjects, it is helpful to have some phrases on hand that will cue the reader to such analysis. See Table 10.3 "Phrases of Comparison and Contrast" for examples.

Table 10.3 Phrases of Comparison and Contrast

| Comparison | Contrast |

|---|---|

| one similarity | one difference |

| another similarity | another difference |

| both | conversely |

| like | in contrast |

| likewise | unlike |

| similarly | while |

| in a similar fashion | whereas |

Exercise 3

Create an outline for each of the items you chose in Note 10.72 "Exercise 1" and Note 10.73 "Exercise 2". Use the point-by-point organizing strategy for one of them, and use the subject organizing strategy for the other.

Writing a Comparison and Contrast Essay

First choose whether you want to compare seemingly disparate subjects, contrast seemingly similar subjects, or compare and contrast subjects. Once you have decided on a topic, introduce it with an engaging opening paragraph. Your thesis should come at the end of the introduction, and it should establish the subjects you will compare, contrast, or both as well as state what can be learned from doing so.

The body of the essay can be organized in one of two ways: by subject or by individual points. The organizing strategy that you choose will depend on, as always, your audience and your purpose. You may also consider your particular approach to the subjects as well as the nature of the subjects themselves; some subjects might better lend themselves to one structure or the other. Make sure to use comparison and contrast phrases to cue the reader to the ways in which you are analyzing the relationship between the subjects.

After you finish analyzing the subjects, write a conclusion that summarizes the main points of the essay and reinforces your thesis. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample compare-and-contrast essay.

Writing at Work

Many business presentations are conducted using comparison and contrast. The organizing strategies—by subject or individual points—could also be used for organizing a presentation. Keep this in mind as a way of organizing your content the next time you or a colleague have to present something at work.

Exercise 4

Choose one of the outlines you created in Note 10.75 "Exercise 3", and write a full compare-and-contrast essay. Be sure to include an engaging introduction, a clear thesis, well-defined and detailed paragraphs, and a fitting conclusion that ties everything together.

Key Takeaways

- A compare-and-contrast essay analyzes two subjects by either comparing them, contrasting them, or both.

- The purpose of writing a comparison or contrast essay is not to state the obvious but rather to illuminate subtle differences or unexpected similarities between two subjects.

- The thesis should clearly state the subjects that are to be compared, contrasted, or both, and it should state what is to be learned from doing so.

-

There are two main organizing strategies for compare-and-contrast essays.

- Organize by the subjects themselves, one then the other.

- Organize by individual points, in which you discuss each subject in relation to each point.

- Use phrases of comparison or phrases of contrast to signal to readers how exactly the two subjects are being analyzed.

10.8 Cause and Effect

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of cause and effect in writing.

- Understand how to write a cause-and-effect essay.

The Purpose of Cause and Effect in Writing

It is often considered human nature to ask, “why?” and “how?” We want to know how our child got sick so we can better prevent it from happening in the future, or why our colleague a pay raise because we want one as well. We want to know how much money we will save over the long term if we buy a hybrid car. These examples identify only a few of the relationships we think about in our lives, but each shows the importance of understanding cause and effect.

A cause is something that produces an event or condition; an effect is what results from an event or condition. The purpose of the cause-and-effect essayAn essay that tries to determine how various phenomena are related. is to determine how various phenomena relate in terms of origins and results. Sometimes the connection between cause and effect is clear, but often determining the exact relationship between the two is very difficult. For example, the following effects of a cold may be easily identifiable: a sore throat, runny nose, and a cough. But determining the cause of the sickness can be far more difficult. A number of causes are possible, and to complicate matters, these possible causes could have combined to cause the sickness. That is, more than one cause may be responsible for any given effect. Therefore, cause-and-effect discussions are often complicated and frequently lead to debates and arguments.

Tip

Use the complex nature of cause and effect to your advantage. Often it is not necessary, or even possible, to find the exact cause of an event or to name the exact effect. So, when formulating a thesis, you can claim one of a number of causes or effects to be the primary, or main, cause or effect. As soon as you claim that one cause or one effect is more crucial than the others, you have developed a thesis.

Exercise 1

Consider the causes and effects in the following thesis statements. List a cause and effect for each one on your own sheet of paper.

- The growing childhood obesity epidemic is a result of technology.

- Much of the wildlife is dying because of the oil spill.

- The town continued programs that it could no longer afford, so it went bankrupt.

- More young people became politically active as use of the Internet spread throughout society.

- While many experts believed the rise in violence was due to the poor economy, it was really due to the summer-long heat wave.

Exercise 2

Write three cause-and-effect thesis statements of your own for each of the following five broad topics.

- Health and nutrition

- Sports

- Media

- Politics

- History

The Structure of a Cause-and-Effect Essay

The cause-and-effect essay opens with a general introduction to the topic, which then leads to a thesis that states the main cause, main effect, or various causes and effects of a condition or event.

The cause-and-effect essay can be organized in one of the following two primary ways:

- Start with the cause and then talk about the effects.

- Start with the effect and then talk about the causes.

For example, if your essay were on childhood obesity, you could start by talking about the effect of childhood obesity and then discuss the cause or you could start the same essay by talking about the cause of childhood obesity and then move to the effect.

Regardless of which structure you choose, be sure to explain each element of the essay fully and completely. Explaining complex relationships requires the full use of evidence, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and anecdotes.

Because cause-and-effect essays determine how phenomena are linked, they make frequent use of certain words and phrases that denote such linkage. See Table 10.4 "Phrases of Causation" for examples of such terms.

Table 10.4 Phrases of Causation

| as a result | consequently |

| because | due to |

| hence | since |

| thus | therefore |

The conclusion should wrap up the discussion and reinforce the thesis, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of the relationship that was analyzed.

Tip

Be careful of resorting to empty speculation. In writing, speculation amounts to unsubstantiated guessing. Writers are particularly prone to such trappings in cause-and-effect arguments due to the complex nature of finding links between phenomena. Be sure to have clear evidence to support the claims that you make.

Exercise 3

Look at some of the cause-and-effect relationships from Note 10.83 "Exercise 2". Outline the links you listed. Outline one using a cause-then-effect structure. Outline the other using the effect-then-cause structure.

Writing a Cause-and-Effect Essay

Choose an event or condition that you think has an interesting cause-and-effect relationship. Introduce your topic in an engaging way. End your introduction with a thesis that states the main cause, the main effect, or both.

Organize your essay by starting with either the cause-then-effect structure or the effect-then-cause structure. Within each section, you should clearly explain and support the causes and effects using a full range of evidence. If you are writing about multiple causes or multiple effects, you may choose to sequence either in terms of order of importance. In other words, order the causes from least to most important (or vice versa), or order the effects from least important to most important (or vice versa).

Use the phrases of causation when trying to forge connections between various events or conditions. This will help organize your ideas and orient the reader. End your essay with a conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your thesis. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample cause-and-effect essay.

Exercise 4

Choose one of the ideas you outlined in Note 10.85 "Exercise 3" and write a full cause-and-effect essay. Be sure to include an engaging introduction, a clear thesis, strong evidence and examples, and a thoughtful conclusion.

Key Takeaways

- The purpose of the cause-and-effect essay is to determine how various phenomena are related.

- The thesis states what the writer sees as the main cause, main effect, or various causes and effects of a condition or event.

-

The cause-and-effect essay can be organized in one of these two primary ways:

- Start with the cause and then talk about the effect.

- Start with the effect and then talk about the cause.

- Strong evidence is particularly important in the cause-and-effect essay due to the complexity of determining connections between phenomena.

- Phrases of causation are helpful in signaling links between various elements in the essay.

10.9 Persuasion

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of persuasion in writing.

- Identify bias in writing.

- Assess various rhetorical devices.

- Distinguish between fact and opinion.

- Understand the importance of visuals to strengthen arguments.

- Write a persuasive essay.

The Purpose of Persuasive Writing

The purpose of persuasionThe attempt to convince or move others to a certain point of view, or opinion. in writing is to convince, motivate, or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion. The act of trying to persuade automatically implies more than one opinion on the subject can be argued.

The idea of an argument often conjures up images of two people yelling and screaming in anger. In writing, however, an argument is very different. An argumentA reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue in writing is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way. Written arguments often fail when they employ ranting rather than reasoning.

Tip

Most of us feel inclined to try to win the arguments we engage in. On some level, we all want to be right, and we want others to see the error of their ways. More times than not, however, arguments in which both sides try to win end up producing losers all around. The more productive approach is to persuade your audience to consider your opinion as a valid one, not simply the right one.

The Structure of a Persuasive Essay

The following five features make up the structure of a persuasive essay:

- Introduction and thesis

- Opposing and qualifying ideas

- Strong evidence in support of claim

- Style and tone of language

- A compelling conclusion

Creating an Introduction and Thesis

The persuasive essay begins with an engaging introduction that presents the general topic. The thesis typically appears somewhere in the introduction and states the writer’s point of view.

Tip

Avoid forming a thesis based on a negative claim. For example, “The hourly minimum wage is not high enough for the average worker to live on.” This is probably a true statement, but persuasive arguments should make a positive case. That is, the thesis statement should focus on how the hourly minimum wage is low or insufficient.

Acknowledging Opposing Ideas and Limits to Your Argument

Because an argument implies differing points of view on the subject, you must be sure to acknowledge those opposing ideas. Avoiding ideas that conflict with your own gives the reader the impression that you may be uncertain, fearful, or unaware of opposing ideas. Thus it is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

Try to address opposing arguments earlier rather than later in your essay. Rhetorically speaking, ordering your positive arguments last allows you to better address ideas that conflict with your own, so you can spend the rest of the essay countering those arguments. This way, you leave your reader thinking about your argument rather than someone else’s. You have the last word.

Acknowledging points of view different from your own also has the effect of fostering more credibility between you and the audience. They know from the outset that you are aware of opposing ideas and that you are not afraid to give them space.

It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish. In effect, you are conceding early on that your argument is not the ultimate authority on a given topic. Such humility can go a long way toward earning credibility and trust with an audience. Audience members will know from the beginning that you are a reasonable writer, and audience members will trust your argument as a result. For example, in the following concessionary statement, the writer advocates for stricter gun control laws, but she admits it will not solve all of our problems with crime:

Although tougher gun control laws are a powerful first step in decreasing violence in our streets, such legislation alone cannot end these problems since guns are not the only problem we face.

Such a concession will be welcome by those who might disagree with this writer’s argument in the first place. To effectively persuade their readers, writers need to be modest in their goals and humble in their approach to get readers to listen to the ideas. See Table 10.5 "Phrases of Concession" for some useful phrases of concession.

Table 10.5 Phrases of Concession

| although | granted that |

| of course | still |

| though | yet |

Exercise 1

Try to form a thesis for each of the following topics. Remember the more specific your thesis, the better.

- Foreign policy

- Television and advertising

- Stereotypes and prejudice

- Gender roles and the workplace

- Driving and cell phones

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers. Choose the thesis statement that most interests you and discuss why.

Bias in Writing

Everyone has various biases on any number of topics. For example, you might have a bias toward wearing black instead of brightly colored clothes or wearing jeans rather than formal wear. You might have a bias toward working at night rather than in the morning, or working by deadlines rather than getting tasks done in advance. These examples identify minor biases, of course, but they still indicate preferences and opinions.

Handling bias in writing and in daily life can be a useful skill. It will allow you to articulate your own points of view while also defending yourself against unreasonable points of view. The ideal in persuasive writing is to let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and a respectful and reasonable address of opposing sides.

The strength of a personal bias is that it can motivate you to construct a strong argument. If you are invested in the topic, you are more likely to care about the piece of writing. Similarly, the more you care, the more time and effort you are apt to put forth and the better the final product will be.

The weakness of bias is when the bias begins to take over the essay—when, for example, you neglect opposing ideas, exaggerate your points, or repeatedly insert yourself ahead of the subject by using I too often. Being aware of all three of these pitfalls will help you avoid them.

The Use of I in Writing

The use of I in writing is often a topic of debate, and the acceptance of its usage varies from instructor to instructor. It is difficult to predict the preferences for all your present and future instructors, but consider the effects it can potentially have on your writing.

Be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound overly biased. There are two primary reasons:

- Excessive repetition of any word will eventually catch the reader’s attention—and usually not in a good way. The use of I is no different.

- The insertion of I into a sentence alters not only the way a sentence might sound but also the composition of the sentence itself. I is often the subject of a sentence. If the subject of the essay is supposed to be, say, smoking, then by inserting yourself into the sentence, you are effectively displacing the subject of the essay into a secondary position. In the following example, the subject of the sentence is underlined:

Smoking is bad.

I think smoking is bad.

In the first sentence, the rightful subject, smoking, is in the subject position in the sentence. In the second sentence, the insertion of I and think replaces smoking as the subject, which draws attention to I and away from the topic that is supposed to be discussed. Remember to keep the message (the subject) and the messenger (the writer) separate.

Checklist

Developing Sound Arguments

Does my essay contain the following elements?

- An engaging introduction

- A reasonable, specific thesis that is able to be supported by evidence

- A varied range of evidence from credible sources

- Respectful acknowledgement and explanation of opposing ideas

- A style and tone of language that is appropriate for the subject and audience

- Acknowledgement of the argument’s limits

- A conclusion that will adequately summarize the essay and reinforce the thesis

Fact and Opinion

FactsStatements that can be definitely proven; ones that have, in a sense, an objective reality. are statements that can be definitely proven using objective data. The statement that is a fact is absolutely valid. In other words, the statement can be pronounced as true or false. For example, 2 + 2 = 4. This expression identifies a true statement, or a fact, because it can be proved with objective data.

OpinionsPersonal views, or judgments. All opinions are not created equal. An opinion in argumentation must have legitimate backing. are personal views, or judgments. An opinion is what an individual believes about a particular subject. However, an opinion in argumentation must have legitimate backing; adequate evidence and credibility should support the opinion. Consider the credibility of expert opinions. Experts in a given field have the knowledge and credentials to make their opinion meaningful to a larger audience.

For example, you seek the opinion of your dentist when it comes to the health of your gums, and you seek the opinion of your mechanic when it comes to the maintenance of your car. Both have knowledge and credentials in those respective fields, which is why their opinions matter to you. But the authority of your dentist may be greatly diminished should he or she offer an opinion about your car, and vice versa.

In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions. Relying on one or the other will likely lose more of your audience than it gains.

Tip

The word prove is frequently used in the discussion of persuasive writing. Writers may claim that one piece of evidence or another proves the argument, but proving an argument is often not possible. No evidence proves a debatable topic one way or the other; that is why the topic is debatable. Facts can be proved, but opinions can only be supported, explained, and persuaded.

Exercise 2

On a separate sheet of paper, take three of the theses you formed in Note 10.94 "Exercise 1", and list the types of evidence you might use in support of that thesis.

Exercise 3

Using the evidence you provided in support of the three theses in Note 10.100 "Exercise 2", come up with at least one counterargument to each. Then write a concession statement, expressing the limits to each of your three arguments.

Using Visual Elements to Strengthen Arguments

Adding visual elements to a persuasive argument can often strengthen its persuasive effect. There are two main types of visual elements: quantitative visuals and qualitative visuals.

Quantitative visualsVisuals that present data graphically. The purpose of using them is to make logical appeals to the audience. present data graphically. They allow the audience to see statistics spatially. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience. For example, sometimes it is easier to understand the disparity in certain statistics if you can see how the disparity looks graphically. Bar graphs, pie charts, Venn diagrams, histograms, and line graphs are all ways of presenting quantitative data in spatial dimensions.

Qualitative visualsVisuals present images that are to appeal to the audience’s emotions. present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions. Photographs and pictorial images are examples of qualitative visuals. Such images often try to convey a story, and seeing an actual example can carry more power than hearing or reading about the example. For example, one image of a child suffering from malnutrition will likely have more of an emotional impact than pages dedicated to describing that same condition in writing.

Writing at Work

When making a business presentation, you typically have limited time to get across your idea. Providing visual elements for your audience can be an effective timesaving tool. Quantitative visuals in business presentations serve the same purpose as they do in persuasive writing. They should make logical appeals by showing numerical data in a spatial design. Quantitative visuals should be pictures that might appeal to your audience’s emotions. You will find that many of the rhetorical devices used in writing are the same ones used in the workplace. For more information about visuals in presentations, see Chapter 14 "Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas".

Writing a Persuasive Essay

Choose a topic that you feel passionate about. If your instructor requires you to write about a specific topic, approach the subject from an angle that interests you. Begin your essay with an engaging introduction. Your thesis should typically appear somewhere in your introduction.

Start by acknowledging and explaining points of view that may conflict with your own to build credibility and trust with your audience. Also state the limits of your argument. This too helps you sound more reasonable and honest to those who may naturally be inclined to disagree with your view. By respectfully acknowledging opposing arguments and conceding limitations to your own view, you set a measured and responsible tone for the essay.

Make your appeals in support of your thesis by using sound, credible evidence. Use a balance of facts and opinions from a wide range of sources, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and personal anecdotes. Each piece of evidence should be fully explained and clearly stated.

Make sure that your style and tone are appropriate for your subject and audience. Tailor your language and word choice to these two factors, while still being true to your own voice.

Finally, write a conclusion that effectively summarizes the main argument and reinforces your thesis. See Chapter 15 "Readings: Examples of Essays" to read a sample persuasive essay.

Exercise 4

Choose one of the topics you have been working on throughout this section. Use the thesis, evidence, opposing argument, and concessionary statement as the basis for writing a full persuasive essay. Be sure to include an engaging introduction, clear explanations of all the evidence you present, and a strong conclusion.

Key Takeaways

- The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion.

- An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue, in writing, is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way.

- A thesis that expresses the opinion of the writer in more specific terms is better than one that is vague.

- It is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

- It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish through a concession statement.

- To persuade a skeptical audience, you will need to use a wide range of evidence. Scientific studies, opinions from experts, historical precedent, statistics, personal anecdotes, and current events are all types of evidence that you might use in explaining your point.

- Make sure that your word choice and writing style is appropriate for both your subject and your audience.

- You should let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and respectfully and reasonably addressing opposing ideas.

- You should be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound more biased than it needs to.

- Facts are statements that can be proven using objective data.

- Opinions are personal views, or judgments, that cannot be proven.

- In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions.

- Quantitative visuals present data graphically. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience.

- Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions.

10.10 Rhetorical Modes: End-of-Chapter Exercises

Exercises

- The thesis statement is a fundamental element of writing regardless of what rhetorical mode you are writing in. Formulate one more thesis for each of the modes discussed in this chapter.

- Which rhetorical mode seems most aligned with who you are as a person? That is, which mode seems most useful to you? Explain why in a paragraph.

- Over the next week, look closely at the texts and articles you read. Document in a journal exactly what type of rhetorical mode is being used. Sometimes it might be for an entire article, but sometimes you might see different modes within one article. The more you can detect various ways of communicating ideas, the easier it will be to do yourself.