This is “The Basic Building Blocks of Organizational Structure”, section 9.1 from the book Strategic Management: Evaluation and Execution (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

9.1 The Basic Building Blocks of Organizational Structure

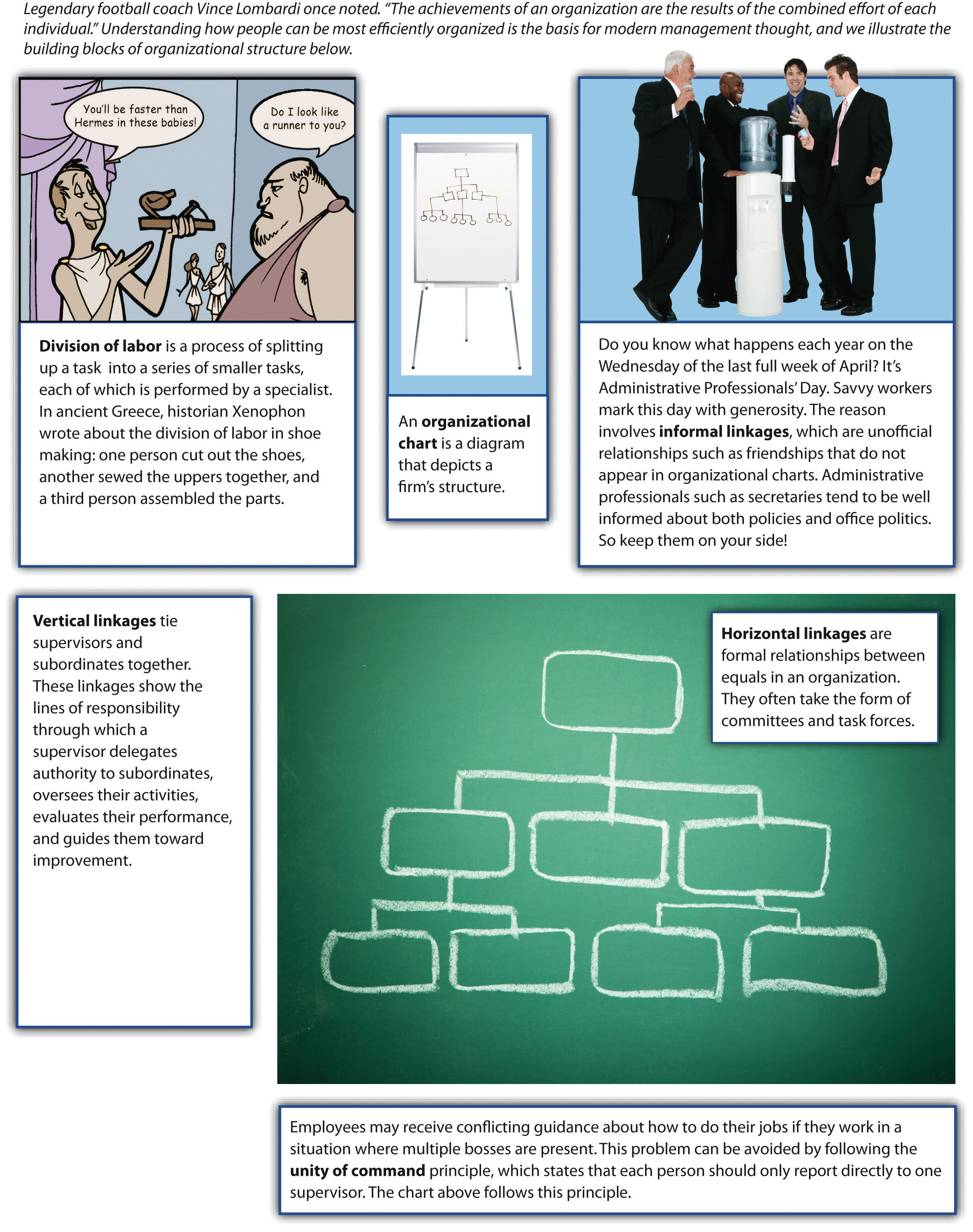

Figure 9.1 The Building Blocks of Organizational Structure

Reprinted with permission from Short, J.C., Bauer, T., Ketchen, D.J. & Simon, L. 2011. Atlas Black: The Complete Adventure. Irvington, NY: Flat World Knowledge (top left); other images © Thinkstock.

Learning Objectives

- Understand what division of labor is and why it is beneficial.

- Distinguish between vertical and horizontal linkages and know what functions each fulfills in an organizational structure.

Division of Labor

General Electric (GE) offers a dizzying array of products and services, including lightbulbs, jet engines, and loans. One way that GE could produce its lightbulbs would be to have individual employees work on one lightbulb at a time from start to finish. This would be very inefficient, however, so GE and most other organizations avoid this approach. Instead, organizations rely on division of laborA process of splitting up a task into a series of smaller tasks, each of which is performed by a specialist. when creating their products (Figure 9.1 "The Building Blocks of Organizational Structure"). Division of labor is a process of splitting up a task (such as the creation of lightbulbs) into a series of smaller tasks, each of which is performed by a specialist.

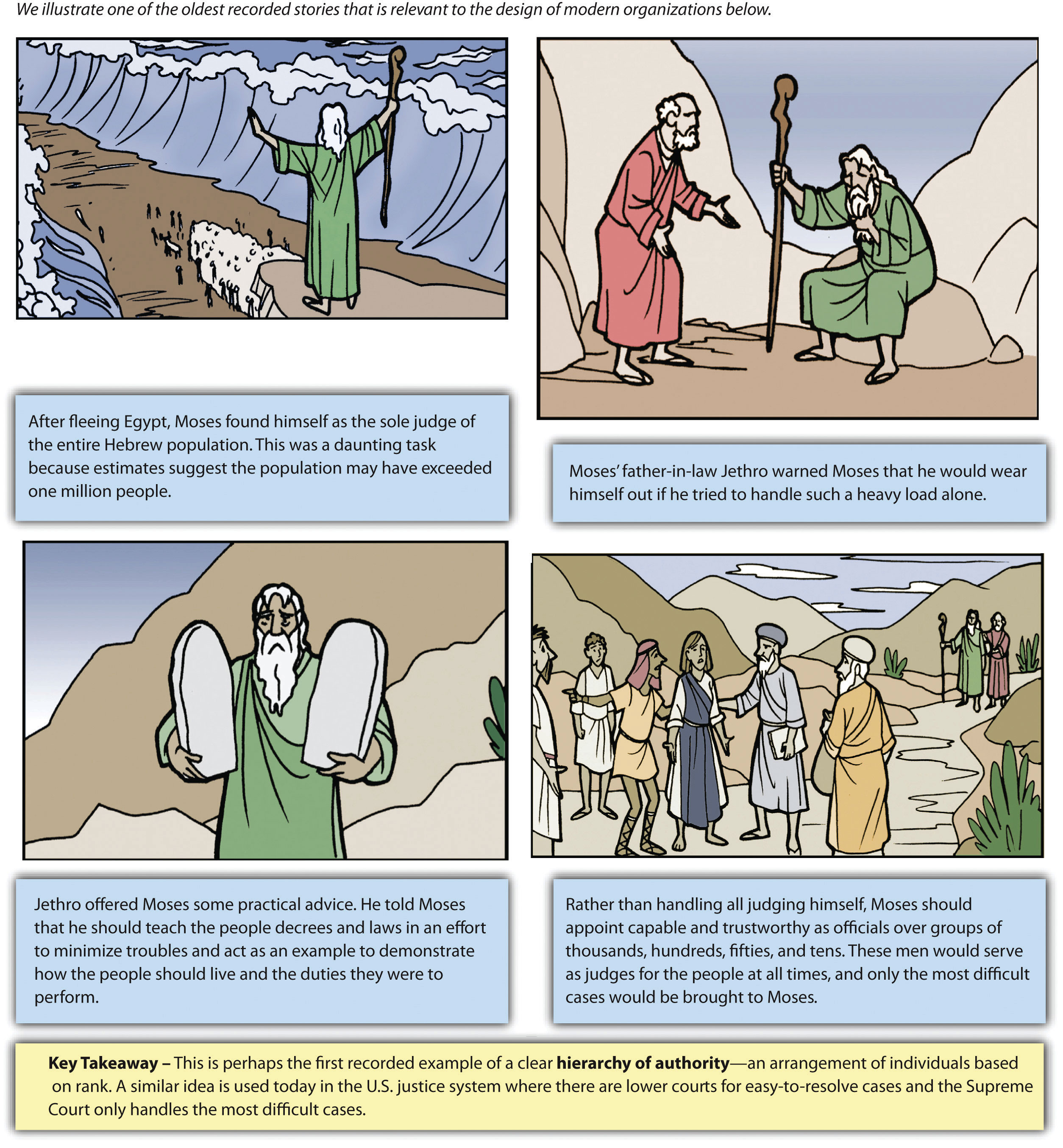

Figure 9.2 Hierarchy of Authority

Reprinted with permission from Short, J.C., Bauer, T., Ketchen, D.J. & Simon, L. 2011. Atlas Black: The Complete Adventure. Irvington, NY: Flat World Knowledge.

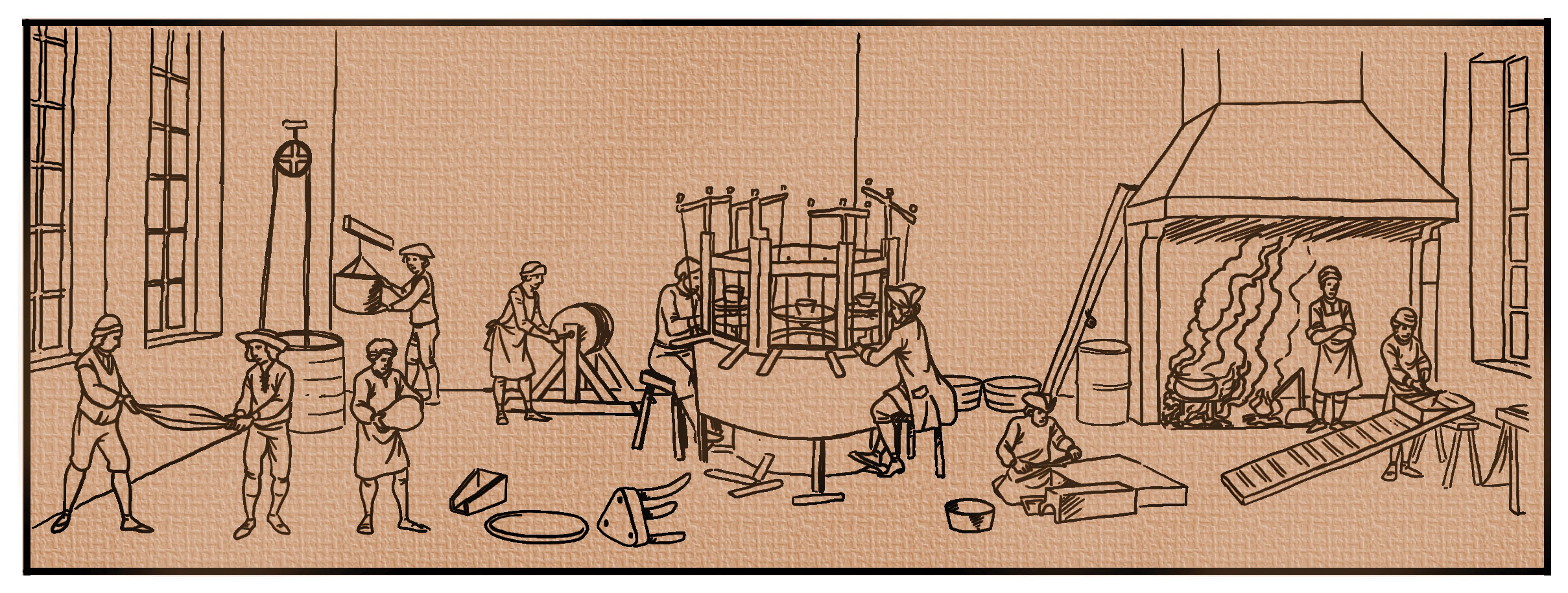

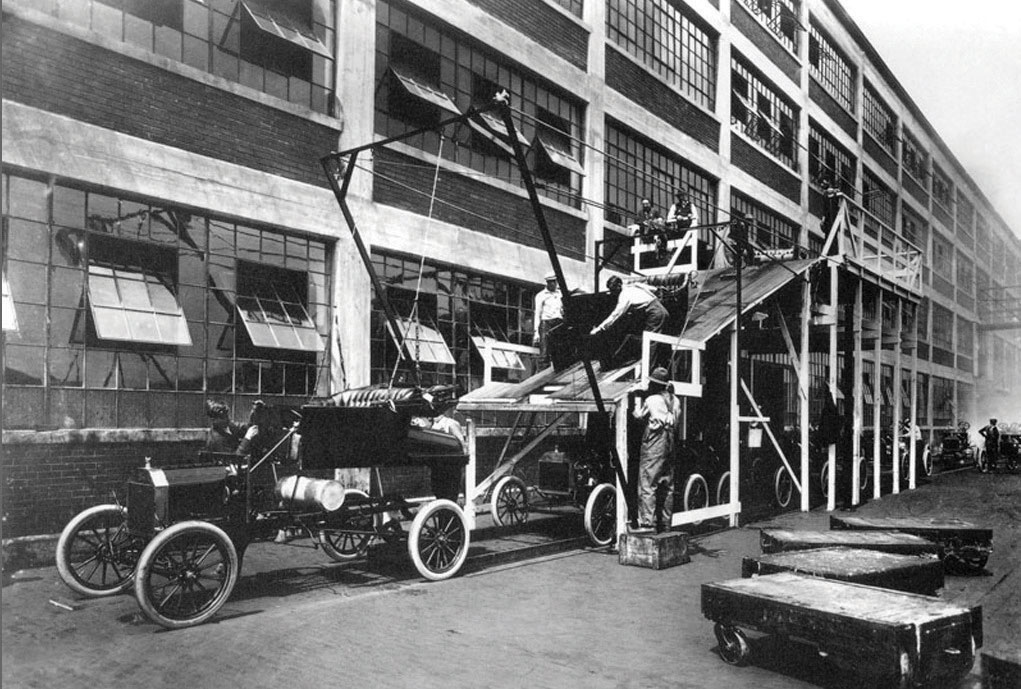

The leaders at the top of organizations have long known that division of labor can improve efficiency. Thousands of years ago, for example, Moses’s creation of a hierarchy of authority by delegating responsibility to other judges offered perhaps the earliest known example (Figure 9.2 "Hierarchy of Authority"). In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith’s book The Wealth of Nations quantified the tremendous advantages that division of labor offered for a pin factory. If a worker performed all the various steps involved in making pins himself, he could make about twenty pins per day. By breaking the process into multiple steps, however, ten workers could make forty-eight thousand pins a day. In other words, the pin factory was a staggering 240 times more productive than it would have been without relying on division of labor. In the early twentieth century, Smith’s ideas strongly influenced Henry Ford and other industrial pioneers who sought to create efficient organizations.

Division of labor allowed eighteenth-century pin factories to dramatically increase their efficiency.

Image courtesy of Short, J. C., Bauer, T., Ketchen, D. J., & Simon, L. 2011. Atlas Black: The Complete Adventure. Irvington, NY: Flat World Knowledge.

While division of labor fuels efficiency, it also creates a challenge—figuring out how to coordinate different tasks and the people who perform them. The solution is organizational structureHow tasks are assigned and grouped together with formal reporting relationships., which is defined as how tasks are assigned and grouped together with formal reporting relationships. Creating a structure that effectively coordinates a firm’s activities increases the firm’s likelihood of success. Meanwhile, a structure that does not match well with a firm’s needs undermines the firm’s chances of prosperity.

Division of labor was central to Henry Ford’s development of assembly lines in his automobile factory. Ford noted, “Nothing is particularly hard if you divide it into small jobs.”

Image courtesy of the Ford Company, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:A-line1913.jpg.

Vertical and Horizontal Linkages

Most organizations use a diagram called an organizational chartA diagram that depicts how firms’ structures are built using two basic building blocks: vertical linkages and horizontal linkages. to depict their structure. These organizational charts show how firms’ structures are built using two basic building blocks: vertical linkages and horizontal linkages. Vertical linkagesRelationships within an organizational structure that show the lines of responsibility through which a supervisor delegates authority to subordinates, oversees their activities, evaluates their performance, and guides them toward improvement when necessary. tie supervisors and subordinates together. These linkages show the lines of responsibility through which a supervisor delegates authority to subordinates, oversees their activities, evaluates their performance, and guides them toward improvement when necessary. Every supervisor except for the person at the very top of the organization chart also serves as a subordinate to someone else. In the typical business school, for example, a department chair supervises a set of professors. The department chair in turn is a subordinate of the dean.

Most executives rely on the unity of commandThe principle that each person within an organization should only report directly to one supervisor. principle when mapping out the vertical linkages in an organizational structure. This principle states that each person should only report directly to one supervisor. If employees have multiple bosses, they may receive conflicting guidance about how to do their jobs. The unity of command principle helps organizations to avoid such confusion. In the case of General Electric, for example, the head of the Energy division reports only to the chief executive officer. If problems were to arise with executing the strategic move discussed in this chapter’s opening vignette—joining the John Wood Group PLC with GE’s Energy division—the head of the Energy division reports would look to the chief executive officer for guidance.

Horizontal linkagesRelationships between equals in an organization. are relationships between equals in an organization. Often these linkages are called committees, task forces, or teams. Horizontal linkages are important when close coordination is needed across different segments of an organization. For example, most business schools revise their undergraduate curriculum every five or so years to ensure that students are receiving an education that matches the needs of current business conditions. Typically, a committee consisting of at least one professor from every academic area (such as management, marketing, accounting, and finance) will be appointed to perform this task. This approach helps ensure that all aspects of business are represented appropriately in the new curriculum.

Committee meetings can be boring, but they are often vital for coordinating efforts across departments.

© Thinkstock

Organic grocery store chain Whole Foods Market is a company that relies heavily on horizontal linkages. As noted on their website, “At Whole Foods Market we recognize the importance of smaller tribal groupings to maximize familiarity and trust. We organize our stores and company into a variety of interlocking teams. Most teams have between 6 and 100 Team Members and the larger teams are divided further into a variety of sub-teams. The leaders of each team are also members of the Store Leadership Team and the Store Team Leaders are members of the Regional Leadership Team. This interlocking team structure continues all the way upwards to the Executive Team at the highest level of the company.”John Mackey’s blog. 2010, March 9. Creating the high trust organization [Web blog post]. Retrieved from http://www2.wholefoodsmarket.com/blogs/jmackey/2010/03/09/creating-the-high-trust-organization/ This emphasis on teams is intended to develop trust throughout the organization, as well as to make full use of the talents and creativity possessed by every employee.

Informal Linkages

Informal linkagesUnofficial relationships such as personal friendships, rivalries, and politics. refer to unofficial relationships such as personal friendships, rivalries, and politics. In the long-running comedy series The Simpsons, Homer Simpson is a low-level—and very low-performing—employee at a nuclear power plant. In one episode, Homer gains power and influence with the plant’s owner, Montgomery Burns, which far exceeds Homer’s meager position in the organization chart, because Mr. Burns desperately wants to be a member of the bowling team that Homer captains. Homer tries to use his newfound influence for his own personal gain and naturally the organization as a whole suffers. Informal linkages such as this one do not appear in organizational charts, but they nevertheless can have (and often do have) a significant influence on how firms operate.

Key Takeaway

- The concept of division of labor (dividing organizational activities into smaller tasks) lies at the heart of the study of organizational structure. Understanding vertical, horizontal, and informal linkages helps managers to organize better the different individuals and job functions within a firm.

Exercises

- How is division of labor used when training college or university football teams? Do you think you could use a different division of labor and achieve more efficiency?

- What are some formal and informal linkages that you have encountered at your college or university? What informal linkages have you observed in the workplace?