This is “Portfolio Planning and Corporate-Level Strategy”, section 8.5 from the book Strategic Management: Evaluation and Execution (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.5 Portfolio Planning and Corporate-Level Strategy

Learning Objectives

- Understand why a firm would want to use portfolio planning.

- Be able to explain the limitations of portfolio planning.

Executives in charge of firms involved in many different businesses must figure out how to manage such portfolios. General Electric (GE), for example, competes in a very wide variety of industries, including financial services, insurance, television, theme parks, electricity generation, lightbulbs, robotics, medical equipment, railroad locomotives, and aircraft jet engines. When leading a company such as GE, executives must decide which units to grow, which ones to shrink, and which ones to abandon.

Portfolio planningA process that helps executives make decisions involving their firms’ various industries. can be a useful tool. Portfolio planning is a process that helps executives assess their firms’ prospects for success within each of its industries, offers suggestions about what to do within each industry, and provides ideas for how to allocate resources across industries. Portfolio planning first gained widespread attention in the 1970s, and it remains a popular tool among executives today.

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Matrix

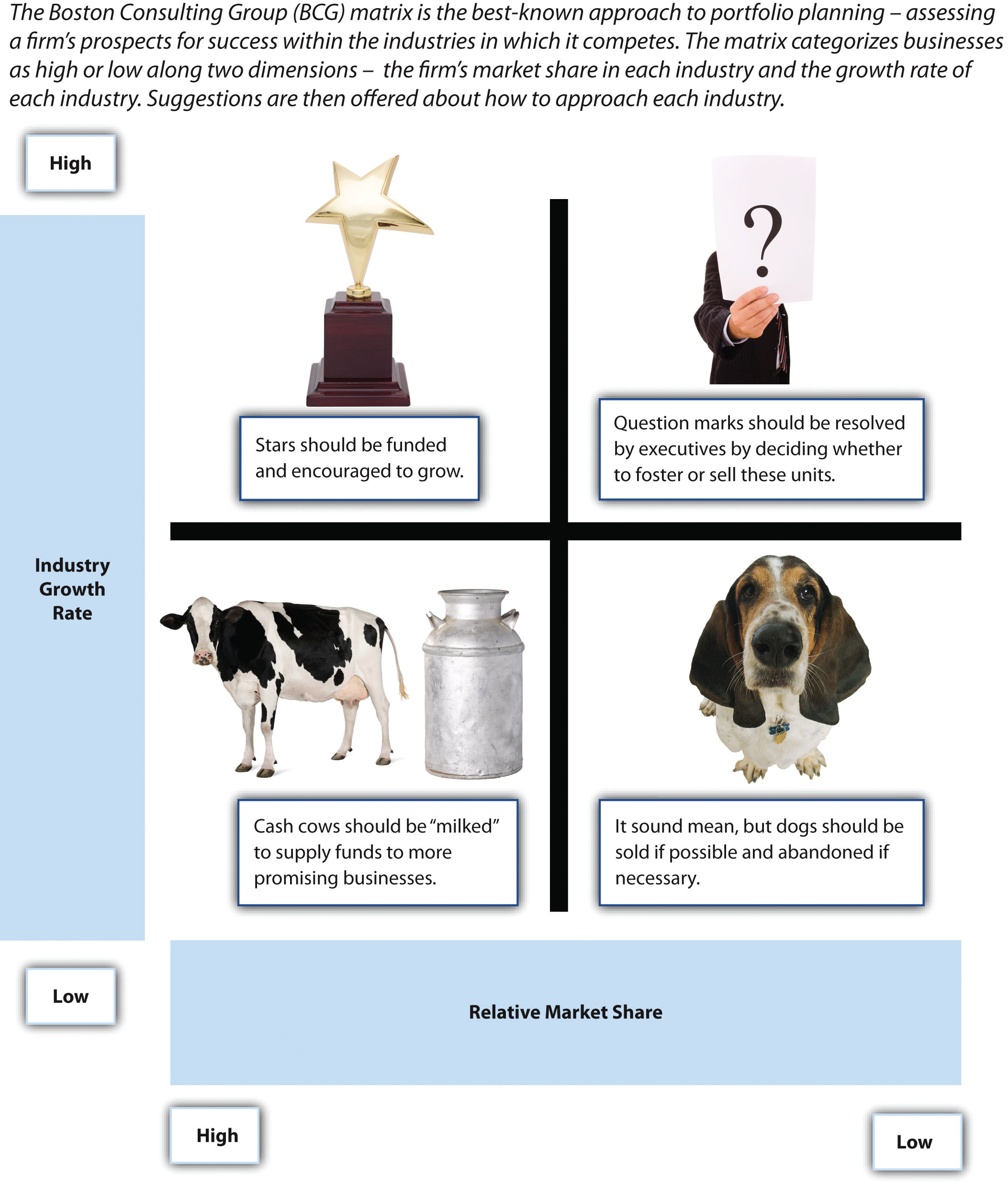

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) matrix is the best-known approach to portfolio planning (Figure 8.7 "The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Matrix"). Using the matrix requires a firm’s businesses to be categorized as high or low along two dimensions: its share of the market and the growth rate of its industry. High market share units within slow-growing industries are called cash cowsHigh market share units within slow-growing industries.. Because their industries have bleak prospects, profits from cash cows should not be invested back into cash cows but rather diverted to more promising businesses. Low market share units within slow-growing industries are called dogsLow market share units within slow-growing industries.. These units are good candidates for divestment. High market share units within fast-growing industries are called starsHigh market share units within fast-growing industries.. These units have bright prospects and thus are good candidates for growth. Finally, low-market-share units within fast-growing industries are called question marksLow market share units within fast-growing industries.. Executives must decide whether to build these units into stars or to divest them.

Owning a puppy is fun, but companies may want to avoid owning units that are considered to be dogs.

Photo courtesy of D. Ketchen.

The BCG matrix is just one portfolio planning technique. With the help of a leading consulting firm, GE developed the attractiveness-strength matrix to examine its diverse activities. This planning approach involves rating each of a firm’s businesses in terms of the attractiveness of the industry and the firm’s strength within the industry. Each dimension is divided into three categories, resulting in nine boxes. Each of these boxes has a set of recommendations associated with it.

Figure 8.7 The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Matrix

© Thinkstock

Limitations to Portfolio Planning

Although portfolio planning is a useful tool, this tool has important limitations. First, portfolio planning oversimplifies the reality of competition by focusing on just two dimensions when analyzing a company’s operations within an industry. Many dimensions are important to consider when making strategic decisions, not just two. Second, portfolio planning can create motivational problems among employees. For example, if workers know that their firm’s executives believe in the BCG matrix and that their subsidiary is classified as a dog, then they may give up any hope for the future. Similarly, workers within cash cow units could become dismayed once they realize that the profits that they help create will be diverted to boost other areas of the firm. Third, portfolio planning does not help identify new opportunities. Because this tool only deals with existing businesses, it cannot reveal what new industries a firm should consider entering.

Key Takeaway

- Portfolio planning is a useful tool for analyzing a firm’s operations, but this tool has limitations. The BCG matrix is one of the most widely used approaches to portfolio planning.

Exercises

- Is market share a good dimension to use when analyzing the prospects of a business? Why or why not?

- What might executives do to keep employees within dog units motivated and focused on their jobs?