This is “The Importance of Socialization”, section 3.1 from the book Sociology: Brief Edition (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.1 The Importance of Socialization

Learning Objective

- Describe why socialization is important for being fully human.

We have just noted that socialization is how culture is learned, but socialization is also important for another important reason. To illustrate this importance, let’s pretend we find a 6-year-old child who has had almost no human contact since birth. After the child was born, her mother changed her diapers and fed her a minimal diet but otherwise did not interact with her. The child was left alone all day and night for years and never went outside. We now find her at age 6. How will her behavior and actions differ from those of the average 6-year-old? Take a moment and write down all the differences you would find.

In no particular order, here is the list you probably wrote. First, the child would not be able to speak; at most, she could utter a few grunts and other sounds. Second, the child would be afraid of us and probably cower in a corner. Third, the child would not know how to play games and interact with us. If we gave her some food and utensils, she would eat with her hands and not know how to use the utensils. Fourth, the child would be unable to express a full range of emotions. For example, she might be able to cry but would not know how to laugh. Fifth, the child would be unfamiliar with, and probably afraid of, our culture’s material objects, including cell phones and televisions. In these and many other respects, this child would differ dramatically from the average 6-year-old youngster in the United States. She would look human, but she would not act human. In fact, in many ways she would act more like a frightened animal than like a young human being, and she would be less able than a typical dog to follow orders and obey commands.

As this example indicates, socialization makes it possible for us to fully function as human beings. Without socialization, we could not have our society and culture. And without social interaction, we could not have socialization. Our example of a socially isolated child was hypothetical, but real-life examples of such children, often called feralA term used for children who have been extremely socially isolated. children, have unfortunately occurred and provide poignant proof of the importance of social interaction for socialization and of socialization for our ability to function as humans.

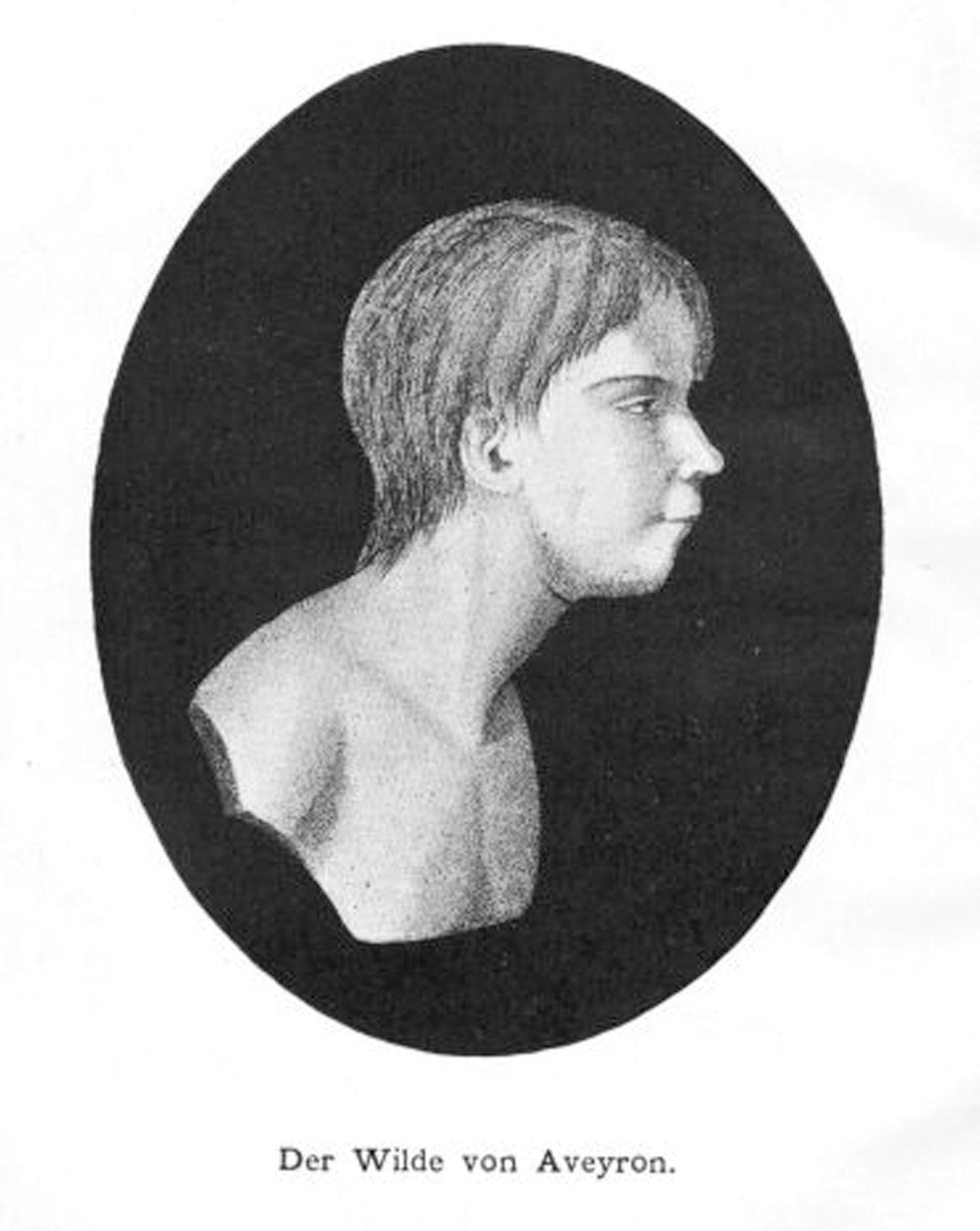

One of the most famous feral children was Victor of Aveyron, who was found wandering in the woods in southern France in 1797. He then escaped custody but emerged from the woods in 1800. Victor was thought to be about age 12 and to have been abandoned some years earlier by his parents; he was unable to speak and acted much more like a wild animal than a human child. Victor first lived in an institution and then in a private home. He never learned to speak, and his cognitive and social development eventually was no better than a toddler’s when he finally died at about age 40 (Lane, 1976).Lane, H. L. (1976). The wild boy of Aveyron. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Figure 3.2

In rare cases, children have grown up in extreme isolation and end up lacking several qualities that make them fully human. This is a photo of Victor of Aveyron, who emerged from the woods in southern France in 1800 after apparently being abandoned by his parents some years earlier. He could not speak, and his cognitive and social skills never advanced beyond those of a small child before he died at the age of 40.

Another such child, found more than about a half-century ago, was called Anna, who “had been deprived of normal contact and had received a minimum of human care for almost the whole of her first six years of life” (Davis, 1940, p. 554).Davis, K. (1940). Extreme social isolation of a child. American Journal of Sociology, 45, 554–565. After being shuttled from one residence to another for her first 5 months, Anna ended up living with her mother in her grandfather’s house and was kept in a small, airless room on the second floor because the grandfather was so dismayed by her birth out of wedlock that he hated seeing her. Because her mother worked all day and would go out at night, Anna was alone almost all the time and lived in filth, often barely alive. Her only food in all those years was milk.

When Anna was found at age 6, she could not talk or walk or “do anything that showed intelligence” (Davis, 1940, p. 554).Davis, K. (1940). Extreme social isolation of a child. American Journal of Sociology, 45, 554–565. She was also extremely undernourished and emaciated. Two years later, she had learned to walk, understand simple commands, feed herself, and remember faces, but she could not talk and in these respects resembled a 1-year-old infant more than the 7-year-old child she really was. By the time she died of jaundice at about age 9, she had acquired the speech of a 2-year-old.

Shortly after Anna was discovered, another girl, called Isabelle, was found in similar circumstances at age 6. She was also born out of wedlock and lived alone with her mother in a dark room isolated from the rest of the mother’s family. Because her mother was mute, Isabelle did not learn to speak, although she did communicate with her mother via some simple gestures. When she was finally found, she acted like a wild animal around strangers, and in other respects she behaved more like a child of 6 months than one of more than 6 years. When first shown a ball, she stared at it, held it in her hand, and then rubbed an adult’s face with it. Intense training afterward helped Isabelle recover, and 2 years later she had reached a normal speaking level for a child her age (Davis, 1940).Davis, K. (1940). Extreme social isolation of a child. American Journal of Sociology, 45, 554–565.

The cases of Anna and Isabelle show that extreme isolation—or, to put it another way, lack of socialization—deprives children of the obvious and not-so-obvious qualities that make them human and in other respects retards their social, cognitive, and emotional development. A series of famous experiments by psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow (1962)Harlow, H. F., & Harlow, M. K. (1962). Social deprivation in monkeys. Scientific American, 207, 137–146. reinforced the latter point by showing it to be true of monkeys as well. The Harlows studied rhesus monkeys that had been removed from their mothers at birth; some were raised in complete isolation, while others were given fake mothers made of cloth and wire with which to cuddle. Neither group developed normally, although the monkeys cuddling with the fake mothers fared somewhat better than those who were totally isolated. In general, the monkeys were not able to interact later with other monkeys, and female infants abused their young when they became mothers. The longer their isolation, the more the monkeys’ development suffered. By showing the dire effects of social isolation, the Harlows’ experiment reinforced the significance of social interaction for normal development. Combined with the tragic examples of feral children, their experiments remind us of the critical importance of socialization and social interaction for human society.

Key Takeaways

- Socialization is the process through which individuals learn their culture and become fully human.

- Unfortunate examples of extreme human isolation illustrate the importance of socialization for children’s social and cognitive development.

For Your Review

- Do you agree that effective socialization is necessary for an individual to be fully human? Could this assumption imply that children with severe developmental disabilities, who cannot undergo effective socialization, are not fully human?

- Do you know anyone with negative views in regard to race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, or religious preference? If so, how do you think this person acquired these views?