This is “The Development of Modern Society”, section 2.4 from the book Sociology: Brief Edition (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

2.4 The Development of Modern Society

Learning Objectives

- Define Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft.

- List the major types of societies that have been distinguished according to their economy and technology.

- Explain why social development produced greater gender and wealth inequality.

Since the origins of sociology during the 19th century, sociologists have tried to understand how and why modern society developed. Part of this understanding involves determining the differences between modern societies and nonmodern (or simple) ones. This chapter has already alluded to some of these differences. In this section, we look at the development of modern society more closely.

One of the key differences between simple and modern societies is the emphasis placed on the community versus the emphasis placed on the individual. As we saw earlier, although community and group commitment remain in modern society, and especially in subcultures like the Amish, in simple societies they are usually the cornerstone of social life. In contrast, modern society is more individualistic and impersonal. Whereas the people in simple societies have close daily ties, in modern societies we have many relationships where we barely know the person. Commitment to the group and community become less important in modern societies, and individualism becomes more important.

Sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies (1887/1963)Tönnies, F. (1963). Community and society. New York, NY: Harper and Row (Original work published 1887) long ago characterized these key characteristics of simple and modern societies with the German words Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Gemeinschaft means human community, and Tönnies said that a sense of community characterizes simple societies, where family, kin, and community ties are quite strong. As societies grew and industrialized and as people moved to cities, Tönnies said, social ties weakened and became more impersonal. Tönnies called this situation a Gesellschaft and found it dismaying.

Other sociologists have distinguished societies according to their type of economy and technology. One of the most useful schemes distinguishes the following types of societies: hunting and gathering, horticultural, pastoral, agricultural, and industrial (Nolan & Lenski, 2009).Nolan, P., & Lenski, G. (2009). Human societies: An introduction to macrosociology. Boulder, CO: Paradigm. Some scholars add a final type, postindustrial, to the end of this list. We now outline the major features of each type in turn. Table 2.2 "Summary of Societal Development" summarizes these features.

Table 2.2 Summary of Societal Development

| Type of society | Key characteristics |

|---|---|

| Hunting and gathering | These are small, simple societies in which people hunt and gather food. Because all people in these societies have few possessions, the societies are fairly egalitarian, and the degree of inequality is very low. |

| Horticultural and pastoral | Horticultural and pastoral societies are larger than hunting and gathering societies. Horticultural societies grow crops with simple tools, while pastoral societies raise livestock. Both types of societies are wealthier than hunting and gathering societies, and they also have more inequality and greater conflict than hunting and gathering societies. |

| Agricultural | These societies grow great numbers of crops, thanks to the use of plows, oxen, and other devices. Compared to horticultural and pastoral societies, they are wealthier and have a higher degree of conflict and of inequality. |

| Industrial | Industrial societies feature factories and machines. They are wealthier than agricultural societies and have a greater sense of individualism and a lower degree of inequality. |

| Postindustrial | These societies feature information technology and service jobs. Higher education is especially important in these societies for economic success. |

Hunting and Gathering Societies

Beginning about 250,000 years ago, hunting and gathering societiesSocieties of a few dozen members whose food is obtained from hunting animals and gathering plants and vegetation. are the oldest ones we know of; few of them remain today, partly because modern societies have encroached on their existence. As the name “hunting and gathering” implies, people in these societies both hunt for food and gather plants and other vegetation. They have few possessions other than some simple hunting and gathering equipment. To ensure their mutual survival, everyone is expected to help find food and also to share the food they find. To seek their food, hunting and gathering peoples often move from place to place. Because they are nomadic, their societies tend to be quite small, often consisting of only a few dozen people.

Beyond this simple summary of the type of life these societies lead, anthropologists have also charted the nature of social relationships in them. One of their most important findings is that hunting and gathering societies are fairly egalitarian. Although men do most of the hunting and women most of the gathering, perhaps reflecting the biological differences between the sexes discussed earlier, women and men in these societies are roughly equal. Because hunting and gathering societies have few possessions, their members are also fairly equal in terms of wealth and power, as virtually no wealth exists.

Horticultural and Pastoral Societies

Horticultural and pastoral societies both developed about 10,000–12,000 years ago. In horticultural societiesSocieties that use the hoe and other simple tools to raise small amounts of crops., people use a hoe and other simple hand tools to raise crops. In pastoral societiesSocieties that raise livestock as their primary source of food., people raise and herd sheep, goats, camels and other domesticated animals and use them as their major source of food and also, depending on the animal, as a means of transportation. Some societies are either primarily horticultural or pastoral, while other societies combine both forms. Pastoral societies tend to be at least somewhat nomadic, as they often have to move to find better grazing land for their animals. Horticultural societies, on the other hand, tend to be less nomadic, as they are able to keep growing their crops in the same location for some time. Both types of societies often manage to produce a surplus of food from vegetable or animal sources, respectively, and this surplus allows them to trade their extra food with other societies. It also allows them to have a larger population size (often reaching several hundred members) than hunting and gathering societies.

Figure 2.21

Horticultural societies often produced an excess of food that allowed them to trade with other societies and also to have more members than hunting and gathering societies.

© Thinkstock

Accompanying the greater complexity and wealth of horticultural and pastoral societies is greater inequality in terms of gender and wealth than is found in hunting and gathering societies. In pastoral societies, wealth stems from the number of animals a family owns, and families with more animals are wealthier and more powerful than families with fewer animals. In horticultural societies, wealth stems from the amount of land a family owns, and families with more land are more wealthy and powerful.

One other side effect of the greater wealth of horticultural and pastoral societies is greater conflict. As just mentioned, sharing of food is a key norm in hunting and gathering societies. In horticultural and pastoral societies, however, their wealth, and more specifically their differences in wealth, leads to disputes and even fighting over land and animals. Whereas hunting and gathering peoples tend to be very peaceful, horticultural and pastoral peoples tend to be more aggressive.

Agricultural Societies

Agricultural societiesSocieties that cultivate large amounts of crops with the plow and other relatively advanced tools and equipment. developed some 5,000 years ago in the Middle East, thanks to the invention of the plow. When pulled by oxen and other large animals, the plow allowed for much more cultivation of crops than the simple tools of horticultural societies permitted. The wheel was also invented about the same time, and written language and numbers began to be used. The development of agricultural societies thus marked a watershed in the development of human society. Ancient Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome were all agricultural societies, and India and many other large nations today remain primarily agricultural.

We have already seen that the greater food production of horticultural and pastoral societies led them to become larger than hunting and gathering societies and to have more trade and greater inequality and conflict. Agricultural societies continue all of these trends. First, because they produce so much more food than horticultural and pastoral societies, they often become quite large, with their numbers sometimes reaching into the millions. Second, their huge food surpluses lead to extensive trade, both within the society itself and with other societies. Third, the surpluses and trade both lead to degrees of wealth unknown in the earlier types of societies and thus to unprecedented inequality, exemplified in the appearance for the first time of peasants, people who work on the land of rich landowners. Finally, agricultural societies’ greater size and inequality also produce more conflict. Some of this conflict is internal, as rich landowners struggle with each other for even greater wealth and power, and peasants sometimes engage in revolts. Other conflict is external, as the governments of these societies seek other markets for trade and greater wealth.

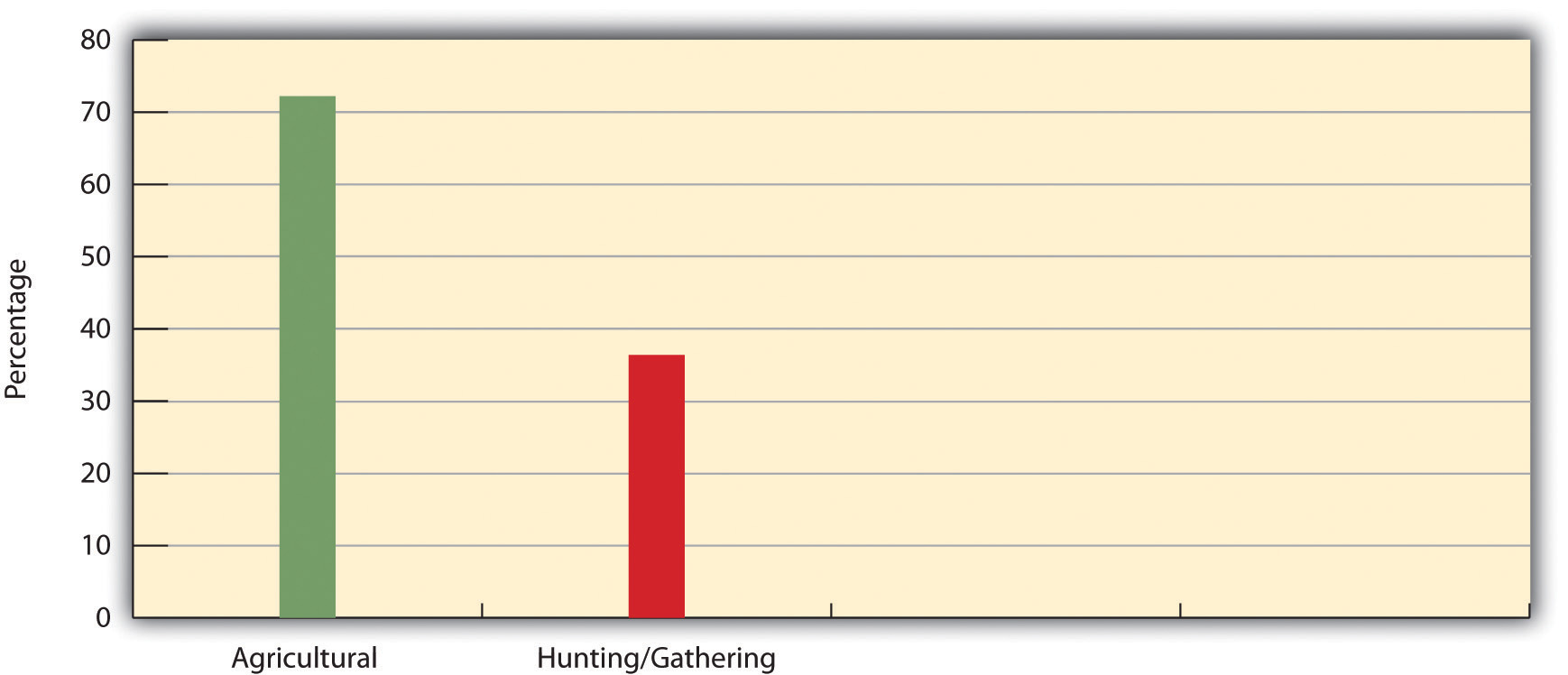

If gender inequality became somewhat greater in horticultural and pastoral societies than in hunting and gathering ones, it became very pronounced in agricultural societies. An important reason for this is the hard, physically taxing work in the fields, much of it using large plow animals, that characterizes these societies. Then, too, women are often pregnant in these societies, because large families provide more bodies to work in the fields and thus more income. Because men do more of the physical labor in agricultural societies—labor on which these societies depend—they have acquired greater power over women (Brettell & Sargent, 2009).Brettell, C. B., & Sargent, C. F. (Eds.). (2009). Gender in cross-cultural perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. In the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, agricultural societies are much more likely than hunting and gathering ones to believe men should dominate women (see Figure 2.22 "Type of Society and Presence of Cultural Belief That Men Should Dominate Women").

Figure 2.22 Type of Society and Presence of Cultural Belief That Men Should Dominate Women

Source: Data from Standard Cross-Cultural Sample.

Industrial Societies

Industrial societiesLarge societies that rely on machines and factories as their primary mode of economic production. emerged in the 1700s as the development of machines and then factories replaced the plow and other agricultural equipment as the primary mode of production. The first machines were steam- and water-powered, but eventually, of course, electricity became the main source of power. The growth of industrial societies marked such a great transformation in many of the world’s societies that we now call the period from about 1750 to the late 1800s the Industrial Revolution. This revolution has had enormous consequences in almost every aspect of society, some for the better and some for the worse.

On the positive side, industrialization brought about technological advances that improved people’s health and expanded their life spans. As noted earlier, there is also a greater emphasis in industrial societies on individualism, and people in these societies typically enjoy greater political freedom than those in older societies. Compared to agricultural societies, industrial societies also have lower economic and gender inequality. In industrial societies, people do have a greater chance to pull themselves up by their bootstraps than was true in earlier societies, and “rags to riches” stories continue to illustrate the opportunity available under industrialization. That said, we will see in later chapters that economic and gender inequality remains substantial in many industrial societies.

On the negative side, industrialization meant the rise and growth of large cities and concentrated poverty and degrading conditions in these cities, as the novels of Charles Dickens poignantly remind us. This urbanization changed the character of social life by creating a more impersonal and less traditional Gesellschaft society. It also led to riots and other urban violence that, among other things, helped fuel the rise of the modern police force and forced factory owners to improve workplace conditions. Today industrial societies consume most of the world’s resources, pollute the environment to an unprecedented degree, and have compiled nuclear arsenals that could undo thousands of years of human society in an instant.

Postindustrial Societies

We are increasingly living in what has been called the information technology age (or just information age), as wireless technology vies with machines and factories as the basis for our economy. Compared to industrial economies, we now have many more service jobs, ranging from housecleaning to secretarial work to repairing computers. Societies in which this is happening are moving from an industrial to a postindustrial phase of development. In postindustrial societiesSocieties in which information technology and service jobs have replaced machines and manufacturing jobs as the primary dimension of the economy., then, information technology and service jobs have replaced machines and manufacturing jobs as the primary dimension of the economy (Bell, 1999).Bell, D. (Ed.). (1999). The coming of post-industrial society: A venture in social forecasting. New York, NY: Basic Books. If the car was the sign of the economic and social times back in the 1920s, then the smartphone or netbook/laptop is the sign of the economic and social future in the early years of the 21st century. If the factory was the dominant workplace at the beginning of the 20th century, with workers standing at their positions by conveyor belts, then cell phone, computer, and software companies are dominant industries at the beginning of the 21st century, with workers, almost all of them much better educated than their earlier factory counterparts, huddled over their wireless technology at home, at work, or on the road. In short, the Industrial Revolution has been replaced by the Information Revolution, and we now have what has been called an information society (Hassan, 2008).Hassan, R. (2008). The information society: Cyber dreams and digital nightmares. Malden, MA: Polity.

As part of postindustrialization in the United States, many manufacturing companies have moved their operations from U.S. cities to overseas sites. Since the 1980s, this process has raised unemployment in cities, many of whose residents lack the college education and other training needed in the information sector. Partly for this reason, some scholars fear that the information age will aggravate the disparities we already have between the “haves” and “have-nots” of society, as people lacking a college education will have even more trouble finding gainful employment than they do now (Wilson, 2009).Wilson, W. J. (2009). The economic plight of inner-city black males. In E. Anderson (Ed.), Against the wall: Poor, young, black, and male (pp. 55–70). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. In the international arena, postindustrial societies may also have a leg up over industrial or, especially, agricultural societies as we move ever more into the information age.

Key Takeaways

- The major types of societies historically have been hunting and gathering, horticultural, pastoral, agricultural, industrial, and postindustrial.

- As societies developed and grew larger, they became more unequal in terms of gender and wealth and also more competitive and even warlike with other societies.

- Postindustrial society emphasizes information technology but also increasingly makes it difficult for individuals without college educations to find gainful employment.

For Your Review

- Explain why societies became more unequal in terms of gender and wealth as they developed and became larger.

- Explain why societies became more individualistic as they developed and became larger.

- Describe the benefits and disadvantages of industrial societies as compared to earlier societies.