This is “Working Groups: Performance and Decision Making”, chapter 11 from the book Social Psychology Principles (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 11 Working Groups: Performance and Decision Making

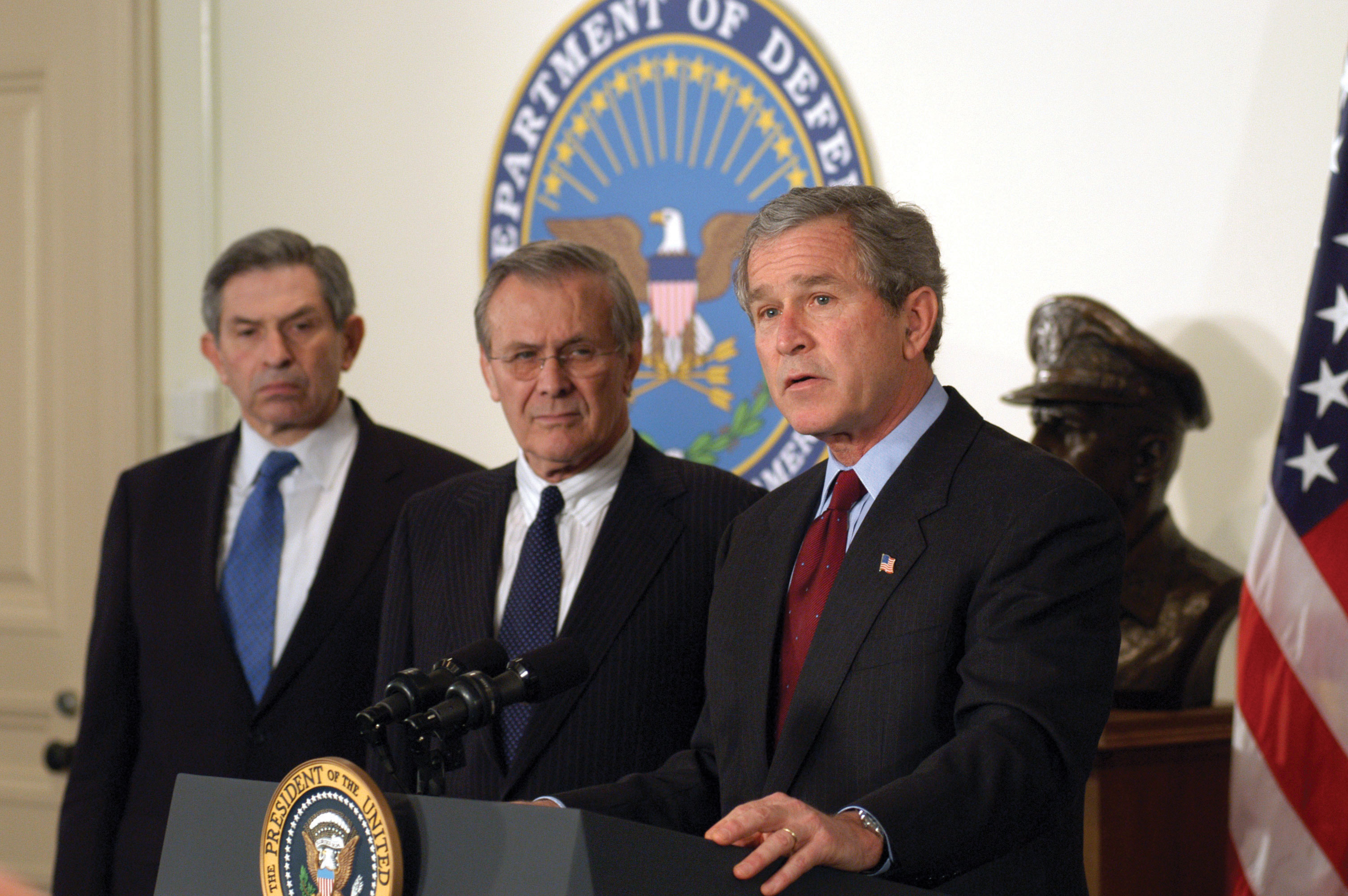

Groupthink and Presidential Decision Making

Source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bush_War_Budget_2003.jpg.

In 2003, President George Bush, in his State of the Union address, made specific claims about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. The president claimed that there was evidence for “500 tons of sarin, mustard and VX nerve agent; mobile biological weapons labs” and “a design for a nuclear weapon.”

But none of this was true, and in 2004, after the war was started, Bush himself called for an investigation of intelligence failures about such weapons preceding the invasion of Iraq.

Many Americans were surprised at the vast failure of intelligence that led the United States into war. In fact, Bush’s decision to go to war based on erroneous facts is part of a long tradition of decision making in the White House.

Psychologist Irving Janis popularized the term groupthink in the 1970s to describe the dynamic that afflicted the Kennedy administration when the president and a close-knit band of advisers authorized the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba in 1961. The president’s view was that the Cuban people would greet the American-backed invaders as liberators who would replace Castro’s dictatorship with democracy. In fact, no Cubans greeted the American-backed force as liberators, and Cuba rapidly defeated the invaders.

The reasons for the erroneous consensus are easy to understand, at least in hindsight. Kennedy and his advisers largely relied on testimony from Cuban exiles, coupled with a selective reading of available intelligence. As is natural, the president and his advisers searched for information to support their point of view. Those supporting the group’s views were invited into the discussion. In contrast, dissenters were seen as not being team players and had difficulty in getting a hearing. Some dissenters feared to speak loudly, wanting to maintain political influence. As the top team became more selective in gathering information, the bias of information that reached the president became ever more pronounced.

A few years later, the administration of President Lyndon Johnson became mired in the Vietnam War. The historical record shows that once again, few voices at the very top levels of the administration gave the president the information he needed to make unbiased decisions. Johnson was frequently told that the United States was winning the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese but was rarely informed that most Vietnamese viewed the Americans as occupiers, not liberators. The result was another presidential example of groupthink, with the president repeatedly surprised by military failures.

How could a president, a generation after the debacles at the Bay of Pigs and in Vietnam, once again fall prey to the well-documented problem of groupthink? The answer, in the language of former Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill, is that Vice President Dick Cheney and his allies formed “a praetorian guard that encircled the president” to block out views they did not like. Unfortunately, filtering dissent is associated with more famous presidential failures than spectacular successes.

Source: Levine, D. I. (2004, February 5). Groupthink and Iraq. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved from http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2004/02/05/EDGV34OCEP1.DTL.

Although people and their worlds have changed dramatically over the course of our history, one fundamental aspect of human existence remains essentially the same. Just as our primitive ancestors lived together in small social groups of families, tribes, and clans, people today still spend a great deal of time in social groups. We go to bars and restaurants, we study together in groups, and we work together on production lines and in businesses. We form governments, play together on sports teams, and use Internet chat rooms and users groups to communicate with others. It seems that no matter how much our world changes, humans will always remain social creatures. It is probably not incorrect to say that the human group is the very foundation of human existence; without our interactions with each other, we would simply not be people, and there would be no human culture.

We can define a social groupA set of individuals who are together with a shared purpose and who normally share a social identity. as a set of individuals with a shared purpose and who normally share a positive social identity. While social groups form the basis of human culture and productivity, they also produce some of our most profound disappointments. Groups sometimes create the very opposite of what we might hope for, such as when a group of highly intelligent advisers lead their president to make a poor decision, when a peaceful demonstration turns into a violent riot, or when the members of a clique at a high school tease other students until they become violent.

In this chapter, we will first consider how social psychologists define social groups. This definition will be important not only in this chapter, which deals with small groups working on projects or making decisions, but also in Chapter 12 "Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination" and Chapter 13 "Competition and Cooperation in Our Social Worlds", in which we will discuss relationships between larger social groups. In this chapter, we will also see that effective group decision making is important in business, education, politics, law, and many other areas (Kovera & Borgida, 2010; Straus, Parker, & Bruce, 2011).Kovera, M. B., & Borgida, E. (2010). Social psychology and law. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1343–1385). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; Straus, S. G., Parker, A. M., & Bruce, J. B. (2011). The group matters: A review of processes and outcomes in intelligence analysis. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 15(2), 128–146. We will close the chapter with a set of recommendations for improving group performance.

Taking all the data together, one psychologist once went so far as to comment that “humans would do better without groups!” (Buys, 1978).Buys, B. J. (1978). Humans would do better without groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4, 123–125. What Buys probably meant by this comment, I think, was to acknowledge the enormous force of social groups and to point out the importance of being aware that these forces can have both positive and negative consequences (Allen & Hecht, 2004; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006; Larson, 2010; Levi, 2007; Nijstad, 2009).Allen, N. J., & Hecht, T. D. (2004). The “romance of teams”: Toward an understanding of its psychological underpinnings and implications. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(4), 439–461. doi: 10.1348/0963179042596469; Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(3), 77–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1529–1006.2006.00030.x; Larson, J. R., Jr. (2010). In search of synergy in small group performance. New York, NY: Psychology Press; Levi, D. (2007). Group dynamics for teams (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Nijstad, B. A. (2009). Group performance. New York, NY: Psychology Press. Keep this important idea in mind as you read this chapter.