This is “Factors That Affect Reaction Rates”, section 14.1 from the book Principles of General Chemistry (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.1 Factors That Affect Reaction Rates

Learning Objective

- To understand the factors that affect reaction rates.

Although a balanced chemical equation for a reaction describes the quantitative relationships between the amounts of reactants present and the amounts of products that can be formed, it gives us no information about whether or how fast a given reaction will occur. This information is obtained by studying the chemical kinetics of a reaction, which depend on various factors: reactant concentrations, temperature, physical states and surface areas of reactants, and solvent and catalyst properties if either are present. By studying the kinetics of a reaction, chemists gain insights into how to control reaction conditions to achieve a desired outcome.

Concentration Effects

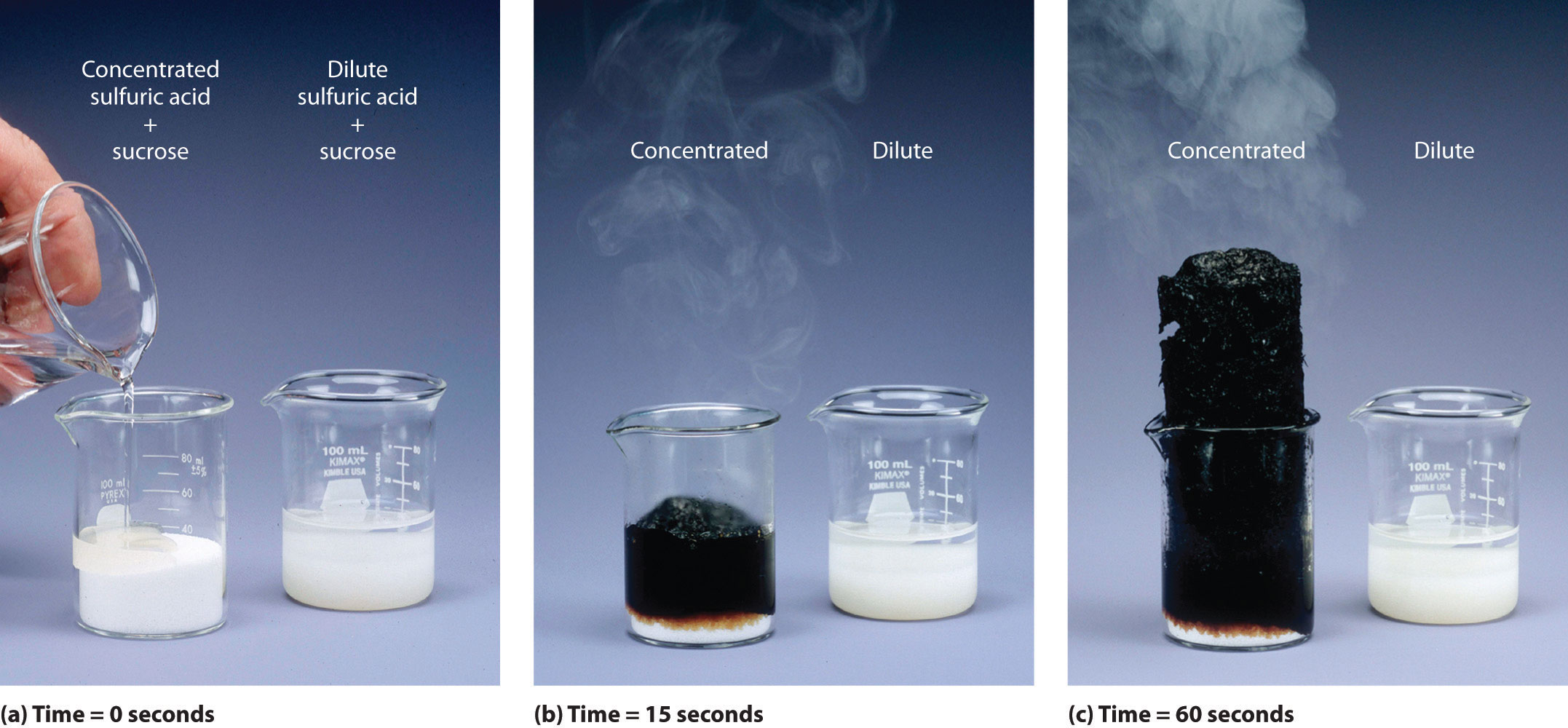

Two substances cannot possibly react with each other unless their constituent particles (molecules, atoms, or ions) come into contact. If there is no contact, the reaction rate will be zero. Conversely, the more reactant particles that collide per unit time, the more often a reaction between them can occur. Consequently, the reaction rate usually increases as the concentration of the reactants increases. One example of this effect is the reaction of sucrose (table sugar) with sulfuric acid, which is shown in Figure 14.1 "The Effect of Concentration on Reaction Rates".

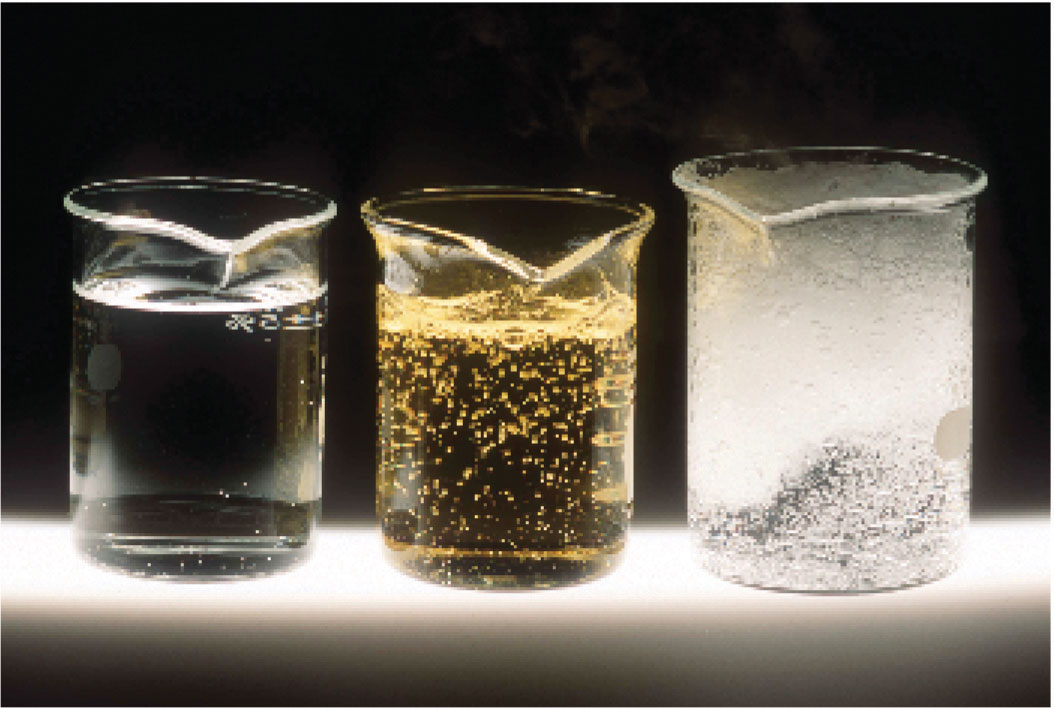

Figure 14.1 The Effect of Concentration on Reaction Rates

Mixing sucrose with dilute sulfuric acid in a beaker (a, right) produces a simple solution. Mixing the same amount of sucrose with concentrated sulfuric acid (a, left) results in a dramatic reaction (b) that eventually produces a column of black porous graphite (c) and an intense smell of burning sugar.

Temperature Effects

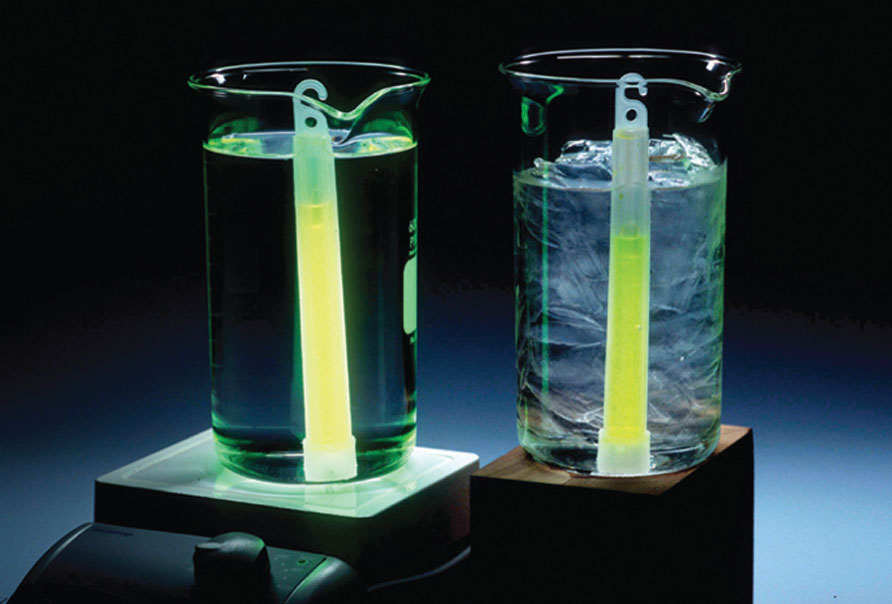

You learned in Chapter 10 "Gases" that increasing the temperature of a system increases the average kinetic energy of its constituent particles. As the average kinetic energy increases, the particles move faster, so they collide more frequently per unit time and possess greater energy when they collide. Both of these factors increase the reaction rate. Hence the reaction rate of virtually all reactions increases with increasing temperature. Conversely, the reaction rate of virtually all reactions decreases with decreasing temperature. For example, refrigeration retards the rate of growth of bacteria in foods by decreasing the reaction rates of biochemical reactions that enable bacteria to reproduce. Figure 14.2 "The Effect of Temperature on Reaction Rates" shows how temperature affects the light emitted by two chemiluminescent light sticks.

Figure 14.2 The Effect of Temperature on Reaction Rates

At high temperature, the reaction that produces light in a chemiluminescent light stick occurs more rapidly, producing more photons of light per unit time. Consequently, the light glows brighter in hot water (left) than in ice water (right).

In systems where more than one reaction is possible, the same reactants can produce different products under different reaction conditions. For example, in the presence of dilute sulfuric acid and at temperatures around 100°C, ethanol is converted to diethyl ether:

Equation 14.1

At 180°C, however, a completely different reaction occurs, which produces ethylene as the major product:

Equation 14.2

Phase and Surface Area Effects

When two reactants are in the same fluid phase, their particles collide more frequently than when one or both reactants are solids (or when they are in different fluids that do not mix). If the reactants are uniformly dispersed in a single homogeneous solution, then the number of collisions per unit time depends on concentration and temperature, as we have just seen. If the reaction is heterogeneous, however, the reactants are in two different phases, and collisions between the reactants can occur only at interfaces between phases. The number of collisions between reactants per unit time is substantially reduced relative to the homogeneous case, and, hence, so is the reaction rate. The reaction rate of a heterogeneous reaction depends on the surface area of the more condensed phase.

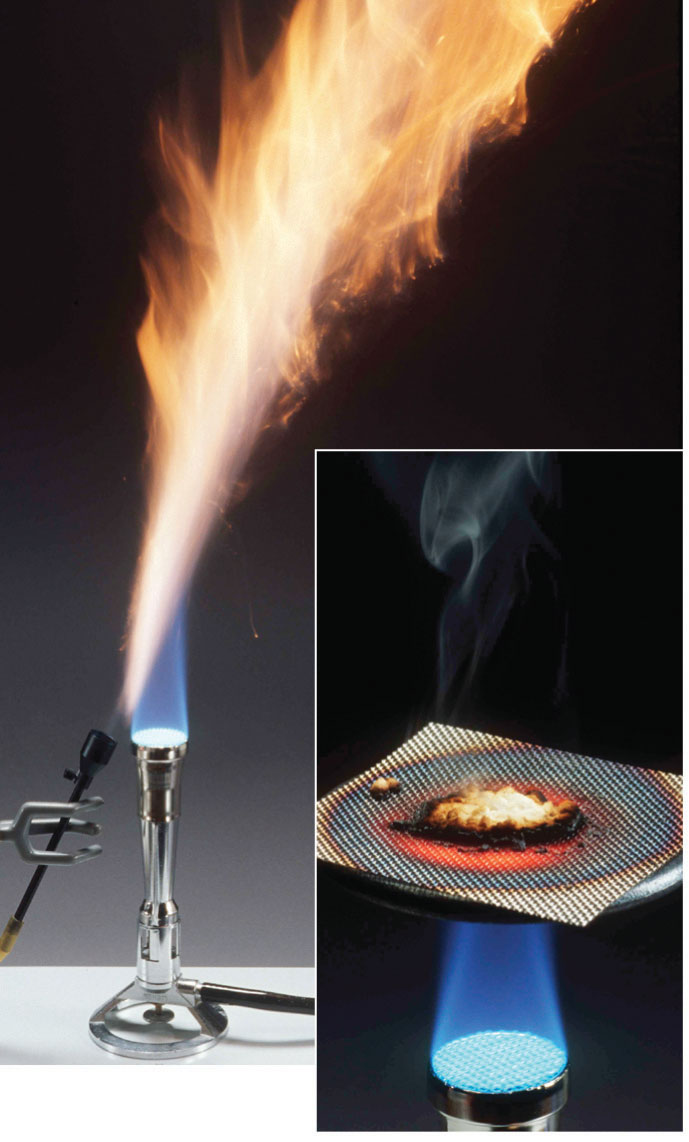

Automobile engines use surface area effects to increase reaction rates. Gasoline is injected into each cylinder, where it combusts on ignition by a spark from the spark plug. The gasoline is injected in the form of microscopic droplets because in that form it has a much larger surface area and can burn much more rapidly than if it were fed into the cylinder as a stream. Similarly, a pile of finely divided flour burns slowly (or not at all), but spraying finely divided flour into a flame produces a vigorous reaction (Figure 14.3 "The Effect of Surface Area on Reaction Rates"). Similar phenomena are partially responsible for dust explosions that occasionally destroy grain elevators or coal mines.

Figure 14.3 The Effect of Surface Area on Reaction Rates

A pile of flour is only scorched by a flame (right), but when the same flour is sprayed into the flame, it burns rapidly (left).

Solvent Effects

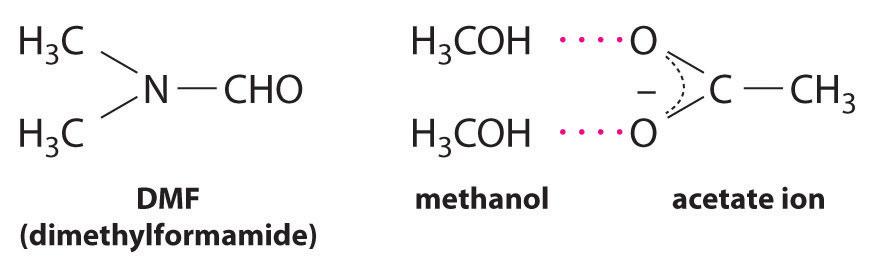

The nature of the solvent can also affect the reaction rates of solute particles. For example, a sodium acetate solution reacts with methyl iodide in an exchange reaction to give methyl acetate and sodium iodide.

Equation 14.3

CH3CO2Na(soln) + CH3I(l) → CH3CO2CH3(soln) + NaI(soln)This reaction occurs 10 million times more rapidly in the organic solvent dimethylformamide [DMF; (CH3)2NCHO] than it does in methanol (CH3OH). Although both are organic solvents with similar dielectric constants (36.7 for DMF versus 32.6 for methanol), methanol is able to hydrogen bond with acetate ions, whereas DMF cannot. Hydrogen bonding reduces the reactivity of the oxygen atoms in the acetate ion.

Solvent viscosity is also important in determining reaction rates. In highly viscous solvents, dissolved particles diffuse much more slowly than in less viscous solvents and can collide less frequently per unit time. Thus the reaction rates of most reactions decrease rapidly with increasing solvent viscosity.

Catalyst Effects

You learned in Chapter 3 "Chemical Reactions" that a catalyst is a substance that participates in a chemical reaction and increases the reaction rate without undergoing a net chemical change itself. Consider, for example, the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide in the presence and absence of different catalysts (Figure 14.4 "The Effect of Catalysts on Reaction Rates"). Because most catalysts are highly selective, they often determine the product of a reaction by accelerating only one of several possible reactions that could occur.

Figure 14.4 The Effect of Catalysts on Reaction Rates

A solution of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) decomposes in water so slowly that the change is not noticeable (left). Iodide ion acts as a catalyst for the decomposition of H2O2, producing oxygen gas. The solution turns brown because of the reaction of H2O2 with I−, which generates small amounts of I3− (center). The enzyme catalase is about 3 billion times more effective than iodide as a catalyst. Even in the presence of very small amounts of enzyme, the decomposition is vigorous (right).

Most of the bulk chemicals produced in industry are formed with catalyzed reactions. Recent estimates indicate that about 30% of the gross national product of the United States and other industrialized nations relies either directly or indirectly on the use of catalysts.

Summary

Factors that influence the reaction rates of chemical reactions include the concentration of reactants, temperature, the physical state of reactants and their dispersion, the solvent, and the presence of a catalyst.

Key Takeaway

- The reaction rate depends on the concentrations of the reactants, the temperature of the reaction, the phase and surface area of the reactants, the solvent, and the presence or the absence of a catalyst.

Conceptual Problems

-

What information can you obtain by studying the chemical kinetics of a reaction? Does a balanced chemical equation provide the same information? Why or why not?

-

If you were tasked with determining whether to proceed with a particular reaction in an industrial facility, why would studying the chemical kinetics of the reaction be important to you?

-

What is the relationship between each of the following factors and the reaction rate: reactant concentration, temperature of the reaction, physical properties of the reactants, physical and chemical properties of the solvent, and the presence of a catalyst?

-

A slurry is a mixture of a finely divided solid with a liquid in which it is only sparingly soluble. As you prepare a reaction, you notice that one of your reactants forms a slurry with the solvent, rather than a solution. What effect will this have on the reaction rate? What steps can you take to try to solve the problem?

-

Why does the reaction rate of virtually all reactions increase with an increase in temperature? If you were to make a glass of sweetened iced tea the old-fashioned way, by adding sugar and ice cubes to a glass of hot tea, which would you add first?

-

In a typical laboratory setting, a reaction is carried out in a ventilated hood with air circulation provided by outside air. A student noticed that a reaction that gave a high yield of a product in the winter gave a low yield of that same product in the summer, even though his technique did not change and the reagents and concentrations used were identical. What is a plausible explanation for the different yields?

-

A very active area of chemical research involves the development of solubilized catalysts that are not made inactive during the reaction process. Such catalysts are expected to increase reaction rates significantly relative to the same reaction run in the presence of a heterogeneous catalyst. What is the reason for anticipating that the relative rate will increase?

-

Water has a dielectric constant more than two times greater than that of methanol (80.1 for H2O and 33.0 for CH3OH). Which would be your solvent of choice for a substitution reaction between an ionic compound and a polar reagent, both of which are soluble in either methanol or water? Why?

Answers

-

Kinetics gives information on the reaction rate and reaction mechanism; the balanced chemical equation gives only the stoichiometry of the reaction.

-

-

Reaction rates generally increase with increasing reactant concentration, increasing temperature, and the addition of a catalyst. Physical properties such as high solubility also increase reaction rates. Solvent polarity can either increase or decrease the reaction rate of a reaction, but increasing solvent viscosity generally decreases reaction rates.

-

-

Increasing the temperature increases the average kinetic energy of molecules and ions, causing them to collide more frequently and with greater energy, which increases the reaction rate. First dissolve sugar in the hot tea, and then add the ice.

-

-

-