This is “National Income and Product Accounts”, section 13.1 from the book Policy and Theory of International Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

13.1 National Income and Product Accounts

Learning Objectives

- Define GDP and understand how it is used as a measure of economic well-being.

- Recognize the limitations of GDP as a measure of well-being.

Many of the key aggregate variables used to describe an economy are presented in a country’s National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA). National income represents the total amount of money that factors of production earn during the course of a year. This mainly includes payments of wages, rents, profits, and interest to workers and owners of capital and property. The national product refers to the value of output produced by an economy during the course of a year. National product, also called national output, represents the market value of all goods and services produced by firms in a country.

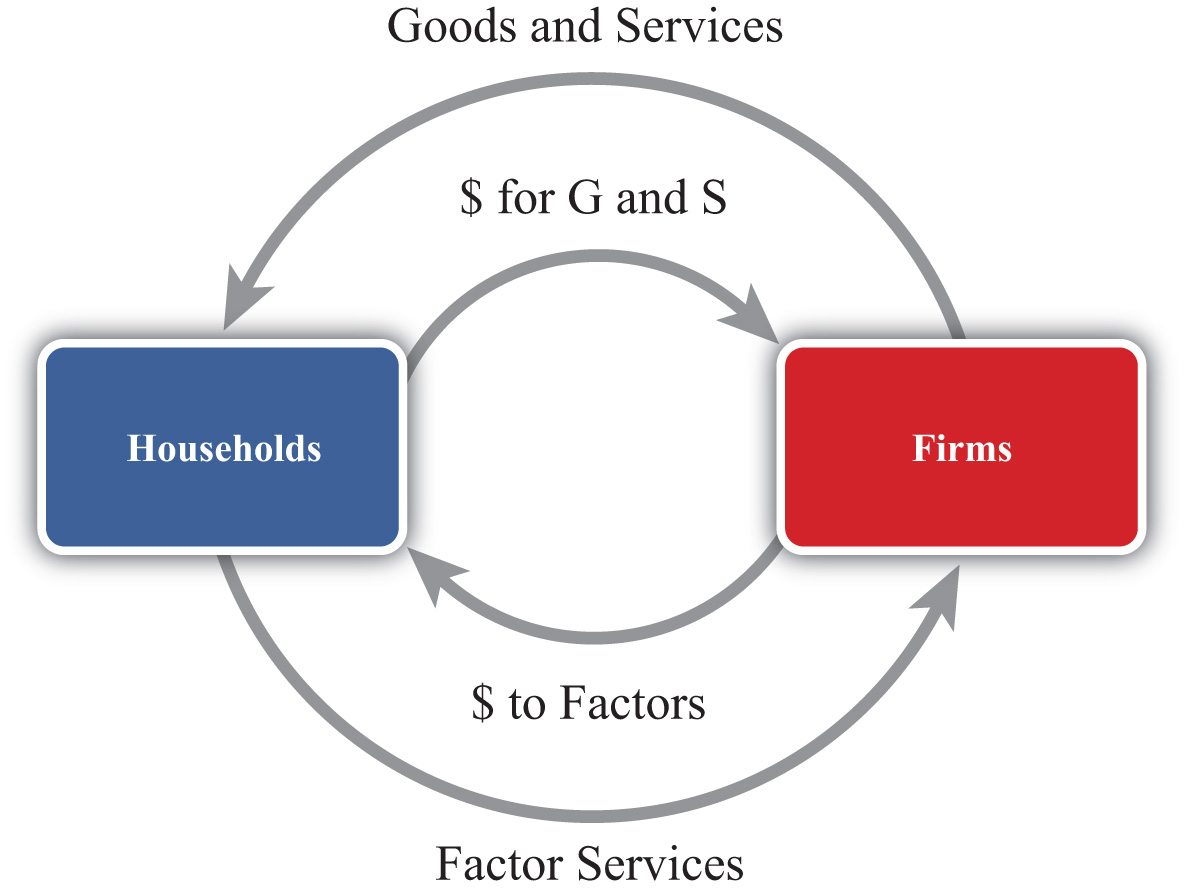

Because of the circular flow of money in exchange for goods and services in an economy, the value of aggregate output (the national product) should equal the value of aggregate income (national income). Consider the adjoining circular flow diagram, Figure 13.1 "A Circular Flow Diagram", describing a very simple economy. The economy is composed of two distinct groups: households and firms. Firms produce all the final goods and services in the economy using factor services (labor and capital) supplied by the households. The households, in turn, purchase the goods and services supplied by the firms. Thus goods and services move between the two groups in the counterclockwise direction. Exchanges are facilitated with the use of money for payments. Thus when firms sell goods and services, the households give the money to the firms in exchange. When the households supply labor and capital to firms, the firms give money to the households in exchange. Thus money flows between the two groups in a clockwise direction.

Figure 13.1 A Circular Flow Diagram

National product measures the monetary flow along the top part of the diagram—that is, the monetary value of goods and services produced by firms in the economy. National income measures the monetary flow along the bottom part of the diagram—that is, the monetary value of all factor services used in the production process. As long as there are no monetary leakages from the system, national income will equal national product.

The national product is commonly referred to as gross domestic product (GDP)Measures the total value of all goods and services produced by a country during a year.. GDP is defined as the value of all final goods and services produced within the borders of a country during some period of time, usually a year. A few things are worth emphasizing about this definition.

First, GDP is measured in terms of the monetary (or dollar) value at which the items exchange in the market. Second, it measures only final goods and services as opposed to intermediate goods. Thus wheat sold by a farmer to a flour mill will not be directly included as part of GDP since the value of the wheat will be included in the value of the flour that the mill sells to the bakery. The value of the flour will in turn be included in the value of the bread sold to the grocery store. Finally, the value of the bread will be included in the price charged by the grocery when the product is finally purchased by the consumer. Only the final bread sale should be included in GDP or else the intermediate values would overstate total production in the economy. Finally, GDP must be distinguished from another common measure of national output, gross national product (GNP)A measure of national income that includes all production by citizens that occurs anywhere in the world. It is measured using the current account balance for exports and imports..

Briefly, GDP measures all production within the borders of the country regardless of who owns the factors used in the production process. GNP measures all production achieved by domestic factors of production regardless of where that production takes place. For example, if a U.S. resident owns a factory in Malaysia and earns profits on the operation of that factory, then those profits would be counted as production by a U.S. factory owner and thus would be included in the U.S. GNP. However, since that production took place beyond U.S. borders, it would not be counted as the U.S. GDP. Alternatively, if a Dutch resident owns a factory in the United States, then the fraction of that production that accrues to the Dutch owner would be counted as part of the U.S. GDP since the production took place in the United States. It would not be counted as part of the U.S. GNP, however, since the production was done by a foreign factor owner.

GDP is probably the most widely reported and closely monitored aggregate statistic. GDP is a measure of the size of an economy. It tells us the total amount of “stuff” the economy produces. Since most of us, as individuals, prefer to have more stuff rather than less, it is straightforward to extend this to the national economy to argue that the higher the GDP, the better off the nation. For this simple reason, statisticians track the growth rate of GDP. Rapid GDP growth is a sign of growing prosperity and economic strength. Falling GDP indicates a recession, and if GDP falls significantly, we call it an economic depression.

For a variety of reasons, GDP should be used only as a rough indicator of the prosperity or welfare of a nation. Indeed, many people contend that GDP is an inadequate measure of national prosperity. Below is a list of some of the reasons why GDP falls short as an indicator of national welfare.

- GDP only measures the amount of goods and services produced during the year. It does not measure the value of goods and services left over from previous years. For example, used cars, two-year-old computers, old furniture, old houses, and so on are all useful and provide welfare to individuals for years after they are produced. Yet the value of these items is only included in GDP in the year in which they are produced. National wealth, on the other hand, measures the value of all goods, services, and assets available in an economy at a point in time and is perhaps a better measure of national economic well-being than GDP.

- GDP, by itself, fails to recognize the size of the population that it must support. If we want to use GDP to provide a rough estimate of the average standard of living among individuals in the economy, then we ought to divide GDP by the population to get per capita GDP. This is often the way in which cross-country comparisons are made.

- GDP gives no account of how the goods and services produced by the economy are distributed among members of the economy. One might prefer a lower GDP with a more equitable distribution to a higher GDP in which a small percentage of the population receives most of the product.

- Measured GDP growth may overstate the growth of the standard of living since price level increases (inflation) would raise measured GDP. Thus even if the economy produces exactly the same amount of goods and services as the year before and prices of those goods rise, then GDP will rise as well. For this reason, real GDP is typically used to measure the growth rate of GDP. Real GDP divides nominal (or measured) GDP by the price level and is designed to eliminate some of the inflationary effects.

- Sometimes, economies with high GDPs may also produce a large amount of negative production externalities. Pollution is one such negative externality. Thus one might prefer to have a lower GDP and less pollution than a higher GDP with more pollution. Some groups also argue that rapid GDP growth may involve severe depletion of natural resources, which may be unsustainable in the long run.

- GDP often rises in the aftermath of natural disasters. Shortly after the Kobe earthquake in Japan in the 1990s, economists predicted that Japan’s GDP would probably rise more rapidly. This is mostly because of the surge of construction activities required to rebuild the damaged buildings. This illustrates why GDP growth may not be indicative of a healthy economy in some circumstances.

- GDP measures the value of production in the economy rather than consumption, which is more important for economic well-being. As will be shown later, national production and consumption are equal when a country’s trade balance is zero; however, if a country has a trade deficit, then its national consumption will exceed its production. Ideally, because consumption is pleasurable while production often is not, we should use the measure of national consumption to measure economic well-being rather than GDP.

Key Takeaways

- GDP is defined as the value of all final goods and services produced within the borders of a country during some period of time, usually a year.

-

The following are several important weaknesses of GDP as a measure of economic well-being:

- GDP measures income, not wealth, and wealth is a better measure of economic well-being.

- GDP does not account for income distribution effects that may be important to economic well-being.

- GDP measures “bads” like pollution as well as “goods.”

- GDP measures production, not consumption, and consumption is more important to economic well-being.

Exercises

-

Jeopardy Questions. As in the popular television game show, you are given an answer to a question and you must respond with the question. For example, if the answer is “a tax on imports,” then the correct question is “What is a tariff?”

- The term for the measure of national output occurring within the nation’s borders.

- The term for the measure of national output that includes all production by domestic factors regardless of location.

- Of income or wealth, this term better describes the gross domestic product (GDP).

- Of income or wealth, this term better describes the gross national product (GNP).

- The term used to describe the measure of GDP that takes account of price level changes or inflationary effects over time.

- The term used to describe the measure of GDP that allows better income comparisons between countries that have different population sizes.

- Many people argue that GDP is an inadequate measure of a nation’s economic well-being. List five reasons why this may be so.

-

GDP is used widely as an indicator of the success and economic well-being of the people of a nation. However, for many reasons it is not the perfect indicator. Briefly comment on the following statements related to this issue:

- Domestic spending is a better indicator of standard of living than GDP.

- National wealth is a better indicator of standard of living than GDP.