This is “Equivalence of an Import Tariff with a Domestic (Consumption Tax plus Production Subsidy)”, section 8.8 from the book Policy and Theory of International Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.8 Equivalence of an Import Tariff with a Domestic (Consumption Tax plus Production Subsidy)

Learning Objective

- Learn that a combination of domestic policies can substitute for a trade policy.

We begin by demonstrating the effects of a consumption tax and a production subsidy applied simultaneously by a small importing country. Then we will show why the net effects are identical to an import tariff applied in the same setting and at the same rate.

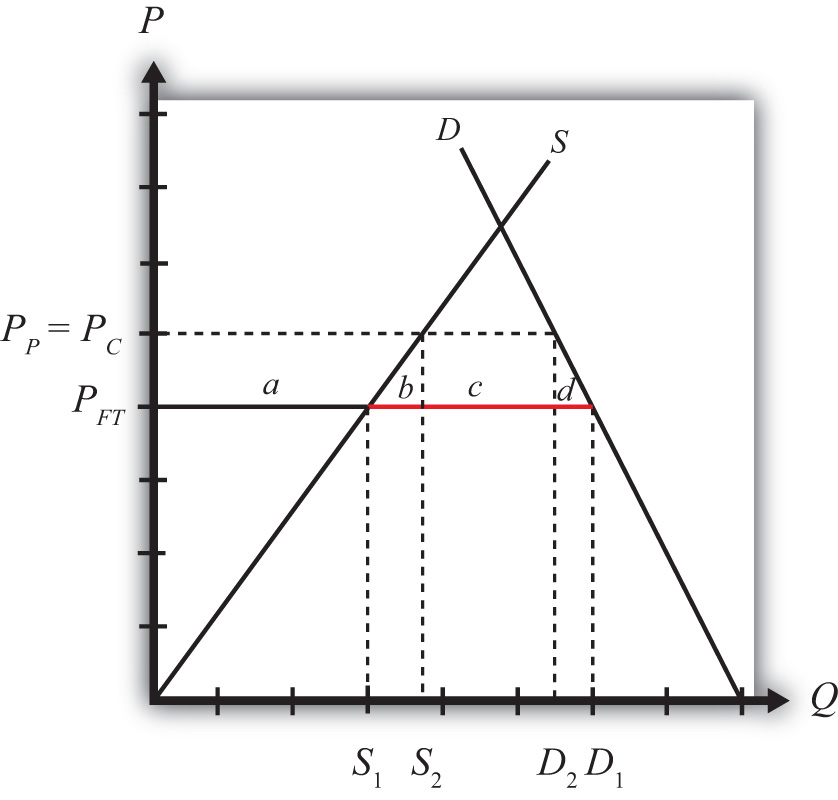

In Figure 8.5 "A Domestic Production Subsidy and Consumption Tax in a Small Importing Country", the free trade price is given by PFT. The domestic supply is S1, and domestic demand is D1, which determines imports in free trade as D1 − S1 (the red line).

Figure 8.5 A Domestic Production Subsidy and Consumption Tax in a Small Importing Country

When a specific consumption tax “t” is implemented, the consumer price increases by the amount of the tax to PC. Because free trade is maintained, the producer’s price would remain at PFT. The increase in the consumer price reduces domestic demand to D2.

When a specific production subsidy “s” is implemented, the producer price will rise by the amount of the tax to PP, but it will not affect the consumer price. As long as the production subsidy and the consumption tax are set at the same value (i.e., t = s), which we will assume, the new producer price will equal the new consumer price (i.e., PC = PP).

The effect of the production subsidy and the consumption tax together is to lower imports from D1 − S1 to D2 − S2.

The combined welfare effects of the production subsidy and consumption tax are shown in Table 8.5 "Static Welfare Effects of a Production Subsidy plus Consumption Tax".

Table 8.5 Static Welfare Effects of a Production Subsidy plus Consumption Tax

| Importing Country | |

|---|---|

| Consumer Surplus | − (a + b + c + d) |

| Producer Surplus | + a |

| Net Govt. Revenue | + c |

| Tax Revenue | + (a + b + c) |

| Subsidy Cost | − (a + b) |

| National Welfare | − (b + d) |

Consumers suffer a loss in surplus because the price they pay rises by the amount of the consumption tax.

Producers gain in terms of producer surplus. The production subsidy raises the price producers receive by the amount of the subsidy, which in turn stimulates an increase in output.

The government receives tax revenue from the consumption tax but must pay for the production subsidy. However, since the subsidy and tax rates are assumed to be identical and since consumption exceeds production (because the country is an importer of the product), the revenue inflow exceeds the outflow. Thus the net effect is a gain in revenue for the government.

In the end, the cost to consumers exceeds the sum of the benefits accruing to producers and the government; thus the net national welfare effect of the two policies is negative.

Notice that these effects are identical to the effects of a tariff applied by a small importing country if the tariff is set at the same rate as the production subsidy and the consumption tax. If a specific tariff, “t,” of the same size as the subsidy and tax were applied, the domestic price would rise to PT = PFT + t. Domestic producers, who are not charged the tariff, would experience an increase in their price to PT. The consumer price would also rise to PT. This means that the producer and consumer welfare effects would be identical to the case of a production subsidy and a consumption tax. The government would only collect a tax on the imported commodities, which implies tariff revenue given by (c). This is exactly equal to the net revenue collected by the government from the production subsidy and consumption tax combined. The net national welfare losses to the economy in both cases are represented by the sum of the production efficiency loss (b) and the consumption efficiency loss (d).

So What?

This equivalence is important because of what might happen after a country liberalizes trade. Many countries have been advised by economists to reduce their tariff barriers in order to enjoy the efficiency benefits that will come with open markets. However, any small country contemplating trade liberalization is likely to be faced with two dilemmas.

First, tariff reductions will quite likely reduce tariff revenue. For many developing countries today, tariff revenue makes up a substantial portion of the government’s total revenue, sometimes as much as 20 percent to 30 percent. This is similar to the early days of currently developed countries. In the 1800s, tariff revenue made up as much as 50 percent of the U.S. federal government’s revenue. In 1790, at the time of the founding of the nation, the U.S. government earned about 90 percent of its revenue from tariff collections. The main reason tariff revenue makes up such a large portion of a developing country’s total government revenue is that tariffs are an administratively simple way to collect revenue. It is much easier than an income tax or profit tax, since those require careful accounting and monitoring. With tariffs, you simply need to park some guards at the ports and borders and collect money as goods come across.

The second problem caused by trade liberalization is that the tariff reductions will injure domestic firms and workers. Tariff reductions will cause domestic prices for imported goods to fall, reducing domestic production and producer surplus and possibly leading to layoffs of workers in the import-competing industries.

Trade-liberalizing countries might like to prevent some of these negative effects from occurring. This section then gives a possible solution. To make up for the lost tariff revenue, a country could simply implement a consumption tax. Consumption taxes are popular forms of taxation around the world. To mitigate the injury to its domestic firms, the country could implement production subsidies, which could forestall the negative impact caused by trade liberalization and could be paid for with extra revenue collected with the consumption tax.

This section demonstrates that if the consumption tax and production subsidy happened to be set on an imported product at equal values and at the same rate as the tariff reduction, then the two domestic policies would combine to fully duplicate the tariff’s effects. In this case, trade liberalization would have no effect.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements have always been cognizant of this particular possibility. The original text says that if after trade liberalization a country takes domestic actions nullifying the benefit that should accrue to the foreign export firms, then a country would be in violation of its GATT (or now WTO) commitments. In other words, it is a GATT/WTO violation to directly substitute domestic policies that duplicate the original effects of the tariff.

Nonetheless, even though a policy response like a production subsidy/consumption tax combination set only on trade liberalized products is unlikely, countries will still feel the effects of lost revenue and injury to import-competing producers. Thus countries will look for ways to compensate for the lost revenue and perhaps help out hard-hit industries.

This section shows that to the extent those responses affect imported products, they can somewhat offset the effects of trade liberalization. Thus it is well worth knowing that these equivalencies between domestic and trade policies are a possibility.

Key Takeaways

- A domestic consumption tax on a product imported by a small country plus a domestic production subsidy set at the same rate as the tax has the same price and welfare effects as a tariff set at the same rate on the same imported product.

- The effects of trade liberalization could be offset with a domestic production subsidy and consumption tax combination on the imported good. However, these actions would be a WTO violation for WTO member countries.

Exercise

-

Jeopardy Questions. As in the popular television game show, you are given an answer to a question and you must respond with the question. For example, if the answer is “a tax on imports,” then the correct question is “What is a tariff?”

- The import policy equivalent to a combined domestic production subsidy and consumption tax applied on the same good at the same level.

- Of increase, decrease, or stay the same, the effect on the domestic producer price with a combined domestic production subsidy and consumption tax applied on the same good at the same level.

- Of increase, decrease, or stay the same, the effect on the domestic consumer price with a combined domestic production subsidy and consumption tax applied on the same good at the same level.

- Of increase, decrease, or stay the same, the effect on the foreign price with a combined domestic production subsidy and consumption tax applied by a small country on the same good at the same level.