This is “The Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem”, section 5.9 from the book Policy and Theory of International Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.9 The Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem

Learning Objectives

- Learn the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem highlighting the determinants of the pattern of trade.

- Identify the effects of trade on prices and outputs using a PPF diagram.

The Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) theoremA theorem that predicts the pattern of trade in the H-O model. It states that the capital-abundant country will export the capital-intensive good and the labor-abundant country will export the labor-intensive good. states that a country that is capital abundant will export the capital-intensive good. Likewise, the country that is labor abundant will export the labor-intensive good. Each country exports that good that it produces relatively better than the other country. In this model, a country’s advantage in production arises solely from its relative factor abundancy.

The H-O Theorem Graphical Depiction: Variable Proportions

The H-O model assumes that the two countries (United States and France) have identical technologies, meaning they have the same production functions available to produce steel and clothing. The model also assumes that the aggregate preferences are the same across countries. The only difference that exists between the two countries in the model is a difference in resource endowments. We assume that the United States has relatively more capital per worker in the aggregate than does France. This means that the United States is capital abundant compared to France. Similarly, France, by implication, has more workers per unit of capital in the aggregate and thus is labor abundant compared to the United States. We also assume that steel production is capital intensive and clothing production is labor intensive.

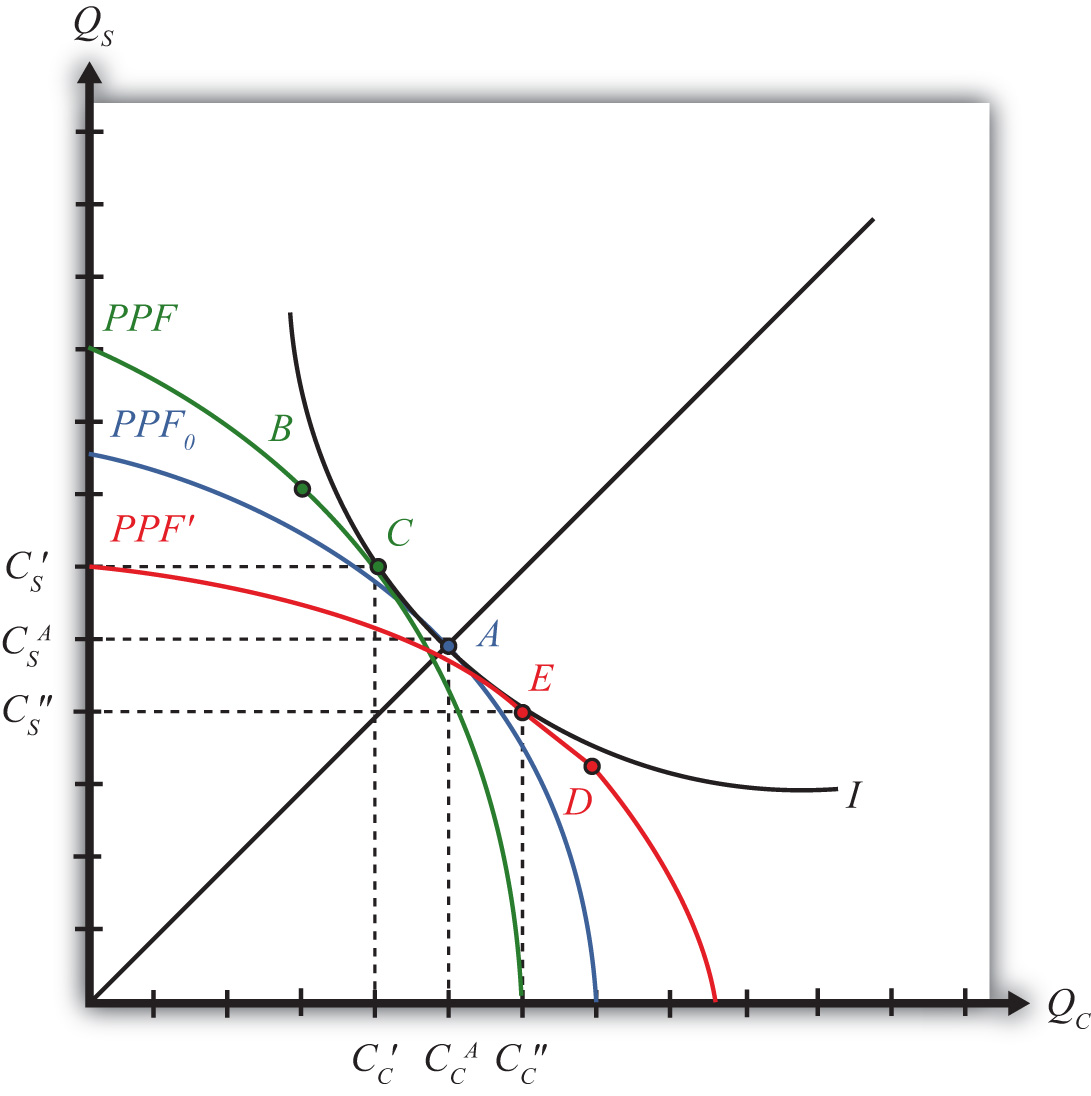

Figure 5.7 Endowment Differences and the PPF

The difference in resource endowments is sufficient to generate different PPFs in the two countries such that equilibrium price ratios would differ in autarky. To see why, imagine first that the two countries are identical in every respect. This means they would have the same PPF (depicted as the blue PPF0 in Figure 5.7 "Endowment Differences and the PPF"), the same set of aggregate indifference curves, and the same autarky equilibrium. Given the assumption about aggregate preferences—that is, U = CCCS—the indifference curve, I, will intersect the countries’ PPF at point A, where the absolute value of the slope of the tangent line (not drawn), PC/PS, is equal to the slope of the ray from the origin through point A. The slope is given by . In other words, the autarky price ratio in each country will be given by

Next, suppose that labor and capital are shifted between the two countries. Suppose labor is moved from the United States to France, while capital is moved from France to the United States. This will have two effects. First, the United States will now have more capital and less labor, and France will have more labor and less capital than it did initially. This implies that K/L> K∗/L∗, or that the United States is capital abundant and France is labor abundant. Second, the two countries’ PPFs will shift. To show how, we apply the Rybczynski theorem.

The United States experiences an increase in K and a decrease in L. Both changes will cause an increase in output of the good that uses capital intensively (i.e., steel) and a decrease in output of the other good (clothing). The Rybczynski theorem is derived assuming that output prices remain constant. Thus if prices did remain constant, production would shift from point A to B and the U.S. PPF would shift from the blue PPF0 to the green PPF in Figure 5.7 "Endowment Differences and the PPF".

Using the new PPF, we can deduce what the U.S. production point and price ratio would be in autarky given the increase in the capital stock and the decline in the labor stock. Consumption could not occur at point B because first, the slope of the PPF at B is the same as the slope at A because the Rybczynski theorem was used to identify it, and second, homothetic preferences imply that the indifference curve passing through B must have a steeper slope because it lies along a steeper ray from the origin.

Thus to find the autarky production point, we simply find the indifference curve that is tangent to the U.S. PPF. This occurs at point C on the new U.S. PPF along the original indifference curve, I. (Note that the PPF was conveniently shifted so that the same indifference curve could be used. Such an outcome is not necessary but does make the graph less cluttered.) The negative of the slope of the PPF at C is given by the ratio of quantities CS′/CC′. Since CS′/CC′ > CSA/CCA, it follows that the new U.S. price ratio will exceed the one prevailing before the capital and labor shift, that is, PC/PS > (PC/PS)0. In other words, the autarky price of clothing is higher in the United States after it experiences the inflow of capital and outflow of labor.

France experiences an increase in L and a decrease in K. These changes will cause an increase in output of the labor-intensive good (i.e., clothing) and a decrease in output of the capital-intensive good (steel). If the price were to remain constant, production would shift from point A to D in Figure 5.7 "Endowment Differences and the PPF", and the French PPF would shift from the blue PPF0 to the red PPF′.

Using the new PPF, we can deduce the French production point and price ratio in autarky given the increase in the capital stock and the decline in the labor stock. Consumption could not occur at point D since homothetic preferences imply that the indifference curve passing through D must have a flatter slope because it lies along a flatter ray from the origin. Thus to find the autarky production point, we simply find the indifference curve that is tangent to the French PPF. This occurs at point E on the red French PPF along the original indifference curve, I. (As before, the PPF was conveniently shifted so that the same indifference curve could be used.) The negative of the slope of the PPF at C is given by the ratio of quantities CS″/CC″. Since CS″/CC″ < CSA/CCA, it follows that the new French price ratio will be less than the one prevailing before the capital and labor shift—that is, PC∗/PS∗ < (PC/PS)0. This means that the autarky price of clothing is lower in France after it experiences the inflow of labor and outflow of capital.

All of the above implies that as one country becomes labor abundant and the other capital abundant, it causes a deviation in their autarky price ratios. The country with relatively more labor (France) is able to supply relatively more of the labor-intensive good (clothing), which in turn reduces the price of clothing in autarky relative to the price of steel. The United States, with relatively more capital, can now produce more of the capital-intensive good (steel), which lowers its price in autarky relative to clothing. These two effects together imply that

Any difference in autarky prices between the United States and France is sufficient to induce profit-seeking firms to trade. The higher price of clothing in the United States (in terms of steel) will induce firms in France to export clothing to the United States to take advantage of the higher price. The higher price of steel in France (in terms of clothing) will induce U.S. steel firms to export steel to France. Thus the United States, abundant in capital relative to France, exports steel, the capital-intensive good. France, abundant in labor relative to the United States, exports clothing, the labor-intensive good. This is the H-O theorem. Each country exports the good intensive in the country’s abundant factor.

Key Takeaways

- The H-O theorem states that a country will export that good that is intensive in the country’s abundant factor.

- In the standard case, a country will produce more of its export good and less of its import good but will continue to produce both. In other words, specialization does not occur as it does in the Ricardian model.

- Trade is motivated by price differences. A capital-abundant (labor-abundant) country exports the capital-intensive (labor-intensive) good because that product price is initially higher in the labor-abundant (capital-abundant) country.

Exercises

- Consider an H-O economy in which there are two countries (United States and France), two goods (wine and cheese), and two factors (capital and labor). Assume the United States is labor abundant and cheese is labor intensive. What is the pattern of trade in free trade? (State what the United States and France import and export.) Which theorem is applied to get this answer? Explain.

-

Suppose two countries, Malaysia and Thailand, can be described by a variable proportions H-O model. Assume they each produce rice and palm oil using labor and capital as inputs. Suppose Malaysia is capital abundant with respect to Thailand and rice production is labor intensive. Suppose the two countries move from autarky to free trade with each other. In the table below, indicate the effect of free trade on the variables listed in the first column in both Malaysia and Thailand. You do not need to show your work. Use the following notation:

+ the variable increases

− the variable decreases

0 the variable does not change

A the variable change is ambiguous (i.e., it may rise, it may fall)

Table 5.9 Effects of Free Trade

| In Malaysia | In Thailand | |

|---|---|---|

| Price Ratio Ppo/Pr | ||

| Output of Palm Oil | ||

| Output of Rice | ||

| Exports of Palm Oil | ||

| Imports of Rice | ||

| Capital-Labor Ratio in Palm Oil Production | ||

| Capital-Labor Ratio in Rice Production |