This is “Mass Media, New Technology, and the Public”, section 16.6 from the book Mass Communication, Media, and Culture (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

16.6 Mass Media, New Technology, and the Public

Learning Objectives

- Explain the technology diffusion model.

- Identify technological failures over the past decade.

- Describe the relationship between mass media and new technology.

When the iPad went on sale in the United States in April 2010, 36-year-old graphic designer Josh Klenert described the device as “ridiculously expensive [and] way overpriced.”Connie Guglielmo, “Apple IPad’s Debut Weekend Sales May Be Surpassing Estimates,” Businessweek, April 4, 2010, http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-04-04/apple-ipad-s-debut-weekend-sales-may-be-surpassing-estimates.html. The cost of the new technology, however, did not deter Klenert from purchasing an iPad; he preordered the tablet computer as soon as it was available and ventured down to Apple’s SoHo store in New York on opening weekend to be one of the first to buy it. Klenert, and everyone else who stood in line at the Apple store during the initial launch of the iPad, is described by sociologists as an early adopter: a tech-loving pioneer who is among the first to embrace new technology as soon as it arrives on the market. What causes a person to be an early adopter or a late adopter? What are the benefits of each? In this section you will read about the cycle of technology and how it is diffused in a society. The process and factors influencing the diffusion of new technology is often discussed in the context of a diffusion model known as the technology adoption life cycleModel that explains the process and factors influencing the diffusion of new technology..

Diffusion of Technology: The Technology Adoption Life Cycle

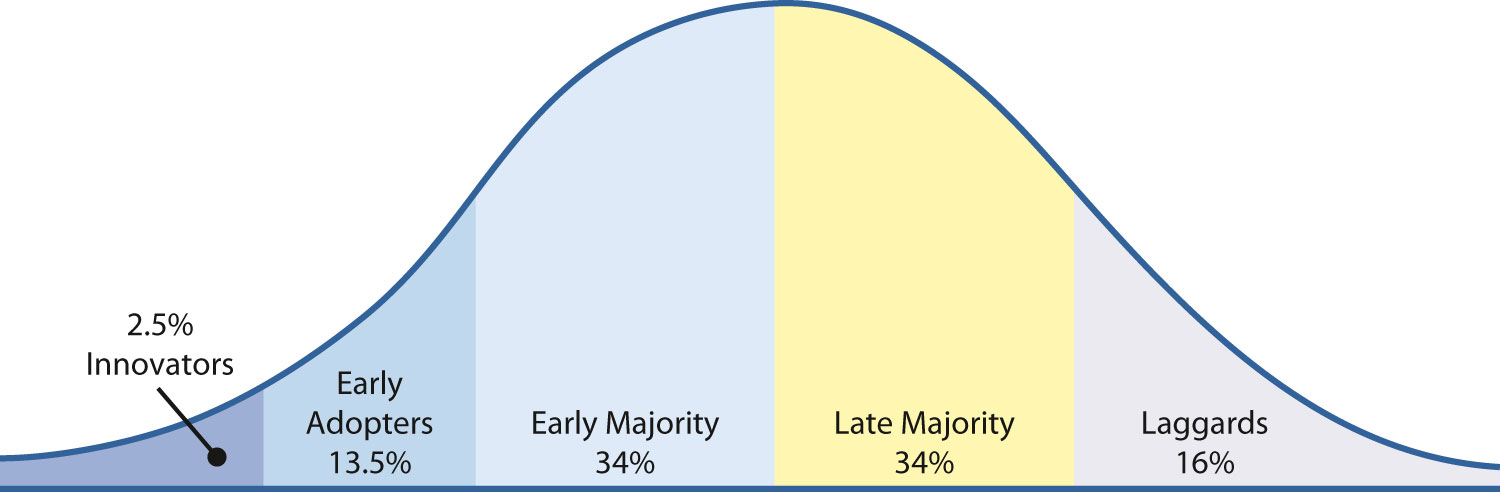

Figure 16.7

Like other cultural shifts, technological advances follow a fairly standard diffusion model.

The technology adoption life cycle was originally observed during the technology diffusion studies of rural sociologists during the 1950s. University researchers George Beal, Joe Bohlen, and Everett Rogers were looking at the adoption rate of hybrid seed among Iowa farmers in an attempt to draw conclusions about how farmers accept new ideas. They discovered that the process of adoption over time fit a normal growth curve pattern—there was a slow gradual rate of adoption, then quite a rapid rate of adoption, followed by a leveling off of the adoption rate. Personal and social characteristics influenced when farmers adopted the use of hybrid seed corn; younger, better-educated farmers tended to adapt to the new technology almost as soon as it became available, whereas older, less-educated farmers waited until most other farms were using hybrid seed before they adopted the process, or they resisted change altogether.

In 1962, Rogers generalized the technology diffusion model in his book Diffusion of Innovations, using the farming research to draw conclusions about the spread of new ideas and technology. Like his fellow farming model researchers, Rogers recognizes five categories of participants: innovatorsExperimentalists who are interested in new technology and are usually the first to acquire it when it reaches the market., who tend to be experimentalists and are interested in the technology itself; early adoptersTechnically sophisticated individuals who usually buy new technology to help solve academic or professional problems. such as Josh Klenert, who are technically sophisticated and are interested in using the technology for solving professional and academic problems; early majorityIndividuals who acquire new technology when it begins to grow in popularity., who constitute the first part of the mainstream, bringing the new technology into common use; late majorityIndividuals who are less comfortable with new technology and are reluctant to change or adapt to it., who are less comfortable with the technology and may be skeptical about its benefits; and laggardsIndividuals who are resistant to new technology and may be critical of its use by others., who are resistant to the new technology and may be critical of its use by others.Everett M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed. (New York: The Free Press, 1995).

When new technology is successfully released in the market, it follows the technology adoption life cycle shown in Figure 16.7. Innovators and early adopters, attracted by something new, want to be the first to possess the innovation, sometimes even before discovering potential uses for it, and are unconcerned with the price. When the iPad hit stores in April 2010, 120,000 units were sold on the first day, primarily as a result of presales.Sam Oliver, “Preorders for Apple iPad Slow After 120K First-Day Rush,” Apple Insider, March 15, 2010, http://www.appleinsider.com/articles/10/03/15/preorders_for_apple_ipad_slow_after_120k_first_day_rush.html. Sales dropped on days 2 and 3, suggesting that demand for the device dipped slightly after the initial first-day excitement. Within the first month, Apple had sold 1,000,000 iPads, exceeding industry expectations.Jim Goldman, “Apple Sells 1 Million iPads,” CNBC, May 3, 2010, http://www.cnbc.com/id/36911690/Apple_Sells_1_Million_iPads. However, many mainstream consumers (the early majority) are waiting to find out just how popular the device will become before making a purchase. Research carried out in the United Kingdom suggests that many consumers are uncertain how the iPad will fit into their lives—the survey drew comments such as “Everything it does I can do on my PC or my phone right now” and “It’s just a big iPod Touch…a big iPhone without the phone.”Steve O’Hear, “Report: The iPad Won’t Go Mass Market Anytime Soon,” TechCrunch, May 12, 2010, http://eu.techcrunch.com/2010/05/12/report-the-ipad-wont-go-mass-market-anytime-soon/. The report, by research group Simpson Carpenter, concludes that most consumers are “unable to find enough rational argument to justify taking the plunge.”Steve O’Hear, “Report: The iPad Won’t Go Mass Market Anytime Soon,” TechCrunch, May 12, 2010, http://eu.techcrunch.com/2010/05/12/report-the-ipad-wont-go-mass-market-anytime-soon/.

However, as with previous technological advances, the early adopters who have jumped on the iPad bandwagon may ultimately validate its potential, helping mainstream users make sense of the device and its uses. Forrester Research notes that much of the equipment acquired by early adopters—laptops, MP3 players, digital cameras, broadband Internet access at home, and mobile phones—is shifting into the mainstream. Analyst Jacqueline Anderson, who works for Forrester, said, “There’s really no group out of the tech loop. America is becoming a digital nation. Technology adoption continues to roll along, picking up more and more mainstream consumers every year.”Jenna Wortham, “The Race to Be an Early Adopter of Technologies Goes Mainstream, a Survey Finds,” New York Times, September 1, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/02/technology/02survey.html. To cite just one example, in 2008 nearly 10 million American households added HDTV, an increase of 27 percent over the previous year.Jenna Wortham, “The Race to Be an Early Adopter of Technologies Goes Mainstream, a Survey Finds,” New York Times, September 1, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/02/technology/02survey.html. By the time most technology reaches mainstream consumers, it is more established, more user-friendly, and cheaper than earlier versions or prototypes. In June 2010, Amazon.com slashed the price of its Kindle e-reader from $259 to $189 and in 2012 to $79 in response to competition from Barnes & Noble’s Nook.Jeffry Bartash, “Amazon Drops Kindle Price to $189,” MarketWatch, June 21, 2010, http://www.marketwatch.com/story/amazon-drops-kindle-price-to-189-2010-06-21. Companies frequently reduce the price of technological devices once the initial novelty wears off, as a result of competition from other manufacturers or as a strategy to retain market share.

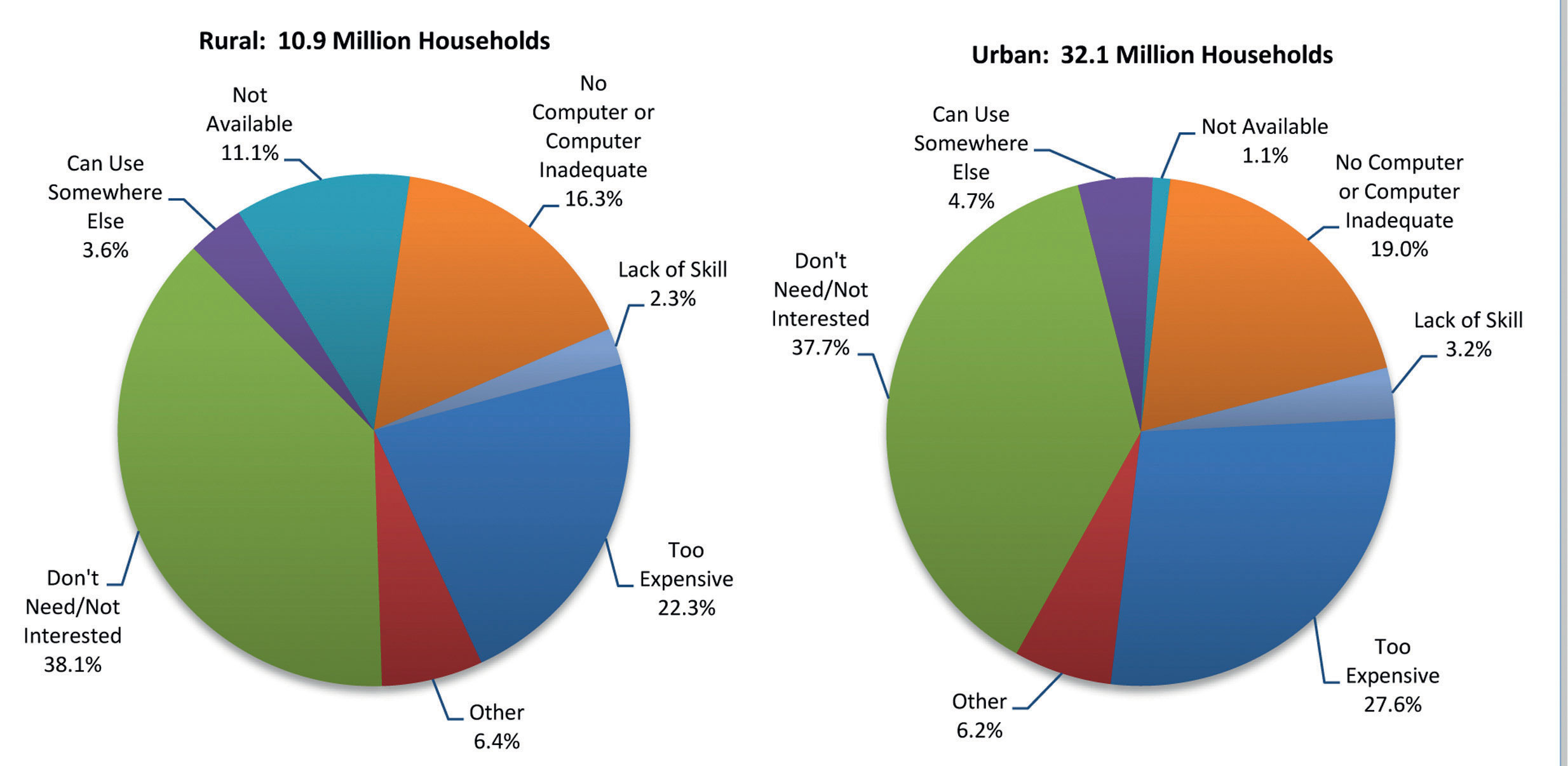

Although many people ultimately adapt to new technology, some are extremely resistant or unwilling to change at all. When Netscape web browser user John Uribe was repeatedly urged by a message from parent company AOL to switch to one of Netscape’s successors, Firefox or Flock, he ignored the suggestions. Despite being informed that AOL would stop providing support for the web browser service in March 2008, Uribe continued to use it. “It’s kind of irrational,” Mr. Uribe said. “It worked for me, so I stuck with it. Until there is really some reason to totally abandon it, I won’t.”Miguel Helft, “Tech’s Late Adopters Prefer the Tried and True,” New York Times, March 12, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/12/technology/12inertia.html. Uribe is a self-confessed late adopter—he still uses dial-up Internet service and is happy to carry on using his aging Dell computer with its small amount of memory. Members of the late majority make up a large percentage of the U.S. population—a 2010 survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau found that despite the technology’s widespread availability, 40 percent of households across the United States have no high-speed or broadband Internet connection, while 30 percent have no Internet at all.Lance Whitney, “Survey: 40 Percent in U.S. Have No Broadband,” CNET, February 16, 2010, http://news.cnet.com/8301-1035_3-10454133-94.html. Of 32.1 million households in urban areas, the most common reason for not having high-speed Internet was a lack of interest or a lack of need for the technology.Lance Whitney, “Survey: 40 Percent in U.S. Have No Broadband,” CNET, February 16, 2010, http://news.cnet.com/8301-1035_3-10454133-94.html.

Figure 16.8

The most common reason that people in both rural and urban areas do not have high-speed Internet is a lack of interest in the technology.

Experts claim that, rather than slowing down the progression of new technological developments, laggards in the technology adoption life cycle may help to control the development of new technology. Paul Saffo, a technology forecaster, said, “Laggards have a bad rap, but they are crucial in pacing the nature of change. Innovation requires the push of early adopters and the pull of laypeople asking whether something really works. If this was a world in which only early adopters got to choose, we’d all be using CB radios and quadraphonic stereo.”Miguel Helft, “Tech’s Late Adopters Prefer the Tried and True,” New York Times, March 12, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/12/technology/12inertia.html. He added that aspects of the laggard and early adopter coexist in most people. For example, many consumers buy the latest digital camera and end up using just a fraction of its functions. Technological laggards may be the reason that not every new technology becomes a mainstream trend (see sidebar).

Not Consumer-Approved: Technological Flops

Have you ever heard of the Apple Newton? How about Microsoft Bob? Or DIVX? For most people, the names probably mean very little because these were all flash-in-the-pan technologies that never caught on with mainstream consumers.

The Apple Newton was an early PDA, officially known as the MessagePad. Introduced by Apple in 1993, the Newton contained many of the features now popularized by modern smartphones, including personal information management and add-on storage slots. Despite clever advertising and relentless word-of-mouth campaigns, the Newton failed to achieve anything like the popularity enjoyed by most Apple products. Hampered by its large size compared to more recent equivalents (such as the PalmPilot) and its cost—basic models cost around $700, with more advanced models costing up to $1,000—the Newton was also ridiculed by talk show comedians and cartoonists because of the supposed inaccuracy of its handwriting-recognition function. By 1998, the Newton was no more. A prime example of an idea that was ahead of its time, the Newton was the forerunner to the smaller, cheaper, and more successful PalmPilot, which in turn paved the way for every successive mobile Internet device.

Even less successful in the late 1990s was DIVX, an attempt by electronics retailer Circuit City to create an alternative to video rental. Customers could rent movies on disposable DIVX discs that they could keep and watch for 2 days. They then had the choice of throwing away or recycling the disc or paying a continuation fee to keep watching it. Viewers who wanted to watch a disc an unlimited amount of times could pay to convert it into a “DIVX silver” disc for an additional fee. Launched in 1998, the DIVX system was promoted as an alternative to traditional rental systems with the promise of no returns and no late fees. However, its introduction coincided with the release of DVD technology, which was gaining traction over the DIVX format. Consumers feared that the choice between DIVX and DVD might turn into another Betamax versus VHS debacle, and by 1999 the technology was all but obsolete. The failure of DIVX cost Circuit City a reported $114,000,000 and left early enthusiasts of the scheme with worthless DIVX equipment (although vendors offered a $100 refund for people who bought a DIVX player).Nick Mokey, “Tech We Regret,” Digital Trends, March 18, 2009, http://www.digitaltrends.com/how-to/tech-we-regret/.

Another catastrophic failure in the world of technology was Microsoft Bob, a mid-1990s attempt to provide a new, nontechnical interface to desktop computing operations. Bob, represented by a logo with a yellow smiley face that filled the o in its name, was supposed to make Windows more palatable to nontechnical users. With a cartoon-like interface that was meant to resemble the inside of a house, Bob helped users navigate their way around the desktop by having them click on objects in each room. Microsoft expected sales of Bob to skyrocket and held a big advertising campaign to celebrate its 1995 launch. Instead, the product failed dismally because of its high initial sale price, demanding hardware requirements, and tendency to patronize users. When Windows 95 was launched the same year, its new Windows Explorer interface required far less dumbing down than previous versions, and Microsoft Bob became irrelevant.

Technological failures such as the Apple Newton, DIVX, and Microsoft Bob prove that sometimes it is better to be a mainstream adopter than to jump on the new-product bandwagon before the technology has been fully tried and tested.

Mass Media Outlets and New Technology

As new technology reaches the shelves and the number of early majority consumers rushing to purchase it increases, mass media outlets are forced to adapt to the new medium. When the iPad’s popularity continued to grow throughout 2010 (selling 3,000,000 units within 3 months of its launch date), traditional newspapers, magazines, and television networks rushed to form partnerships with Apple, launching applications for the tablet so that consumers could directly access their content. Unconstrained by the limited amount of space available in a physical newspaper or magazine, publications such as The New York Times and USA Today are able to include more detailed reporting than they can fit in their traditional paper, as well as interactive features such as crossword puzzles and the use of video and sound. “Our iPad App is designed to take full advantage of the evolving capabilities offered by the Internet,” said Arthur Sulzberger Jr., publisher of The New York Times. “We see our role on the iPad as being similar to our traditional print role—to act as a thoughtful, unbiased filter and to provide our customers with information they need and can trust.”Andy Brett, “The New York Times Introduces an iPad App,” TechCrunch, April 1, 2010, http://techcrunch.com/2010/04/01/new-york-times-ipad/.

Because of Apple’s decision to ban Flash (the dominant software for online video viewing) from the iPad, some traditional television networks have been converting their video files to HTML5 in order to enable full television episodes to be screened on the device. CBS and Disney were among the first networks to offer free television content on the iPad in 2010 through the iPad’s built-in web browser, while ABC streamed its shows via an iPad application. The iPad has even managed to revive forms of traditional media that had been discontinued; in June 2010, Condé Nast announced the restoration of Gourmet magazine as an iPad application called Gourmet Live. As more media content becomes available on new technology such as the iPad, the iPod, and the various e-readers available on the market, it appeals to a broader range of consumers, becoming a self-perpetuating model.

Key Takeaways

- The technology adoption life cycle offers a diffusion model of how people accept new ideas and new technology. The model recognizes five categories of participants: innovators, who tend to be experimentalists and are interested in the technology itself; early adopters, who are technically sophisticated and are interested in using the technology for solving professional and academic problems; early majority, who constitute the first part of the mainstream, bringing the new technology into common use; late majority, who are less comfortable with the technology and may be skeptical about its benefits; and laggards, who are resistant to the new technology and may be critical of its use by others.

- When new technology is released in the market, it follows the technology adoption life cycle. Innovators and early adopters want to be the first to own the technology and are unconcerned about the cost, whereas mainstream consumers wait to find out how popular or successful the technology will become before buying it. As the technology filters into the mainstream, it becomes cheaper and more user-friendly. Some people remain resistant to new technology, however, which helps to control its development. Technological flops such as Microsoft Bob and DIVX result from skeptical late adopters or laggards refusing to purchase innovations that appear unlikely to become commercially successful.

- As new technology transitions into the mainstream, traditional media outlets have to adapt to the new technology to reach consumers. Recent examples include the development of traditional media applications for the iPad, such as newspaper, magazine, and television network apps.

Exercises

Choose a technological innovation from the past 50 years and research its diffusion into the mass market. Then respond to the following short-answer questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Does it fit the technology diffusion model?

- How quickly did the technology reach the mass market? In what ways did mass media aid the spread of this technology?

- Research similar inventions that never caught on. Why do you think this technology succeeded when so many others failed?

End-of-Chapter Assessment

Review Questions

-

Questions for Section 16.1 "Changes in Media Over the Last Century"

- What are the main types of traditional media, and what factors influenced their development?

- What are the main types of new media and what factors influenced their development?

- Why are new media often more successful than traditional media?

-

Questions for Section 16.2 "Information Delivery Methods"

- What were the main types of media used at the beginning of the 20th century?

- What factors led to the rise of a national mass culture?

- How has the Internet affected media delivery?

-

Questions for Section 16.3 "Modern Media Delivery: Pros and Cons"

- What are the main information delivery methods in modern media?

- Why has the Internet become a primary source of news and information?

-

Questions for Section 16.4 "Current Trends in Electronic Media"

- What are the main advantages of modern media delivery methods?

- What are the main disadvantages of modern media delivery methods?

-

Questions for Section 16.5 "Privacy Laws and the Impact of Digital Surveillance"

- What factors influenced the development of the print industry? What factors contributed to its decline?

- How has the Internet affected the print industry?

- What is likely to happen to the print industry in the future? How is print media transitioning into the digital age?

-

Questions for Section 16.6 "Mass Media, New Technology, and the Public"

- What are the current trends in social networking?

- How is the Internet becoming more exclusive?

- What are the effects of smartphone applications on modern media?

Critical Thinking Questions

- Is there a future for traditional media, or will it be consumed by digital technology?

- Do employers have the right to use social networking sites as a method of selecting future employees? Are employees entitled to voice their opinion on the Internet even if it damages their company’s reputation?

- Did the USA PATRIOT Act make the country a safer place, or did it violate privacy laws and undermine civil liberties?

- One of the disadvantages of modern media delivery is the lack of reliability of information on the Internet. Do you think online journalism (including blogging) will ultimately become a respected source of information, or will people continue to rely on traditional news media?

- Will a pay-for-content model work for online newspapers and magazines, or have consumers become too used to receiving their news for free?

Career Connection

As a result of rapid change in the digital age, careers in media are constantly shifting, and many people who work in the industry face an uncertain future. However, the Internet (and all the various technologies associated with it) has created numerous opportunities in the media field. Take a look at the following website and scroll down to the “Digital” section: http://www.getdegrees.com/articles/career-resources/top-60-jobs-that-will-rock-the-future/

The website lists several media careers that are on the rise, including the following:

- Media search consultant

- Interface designer

- Cloud computing engineer

- Integrated digital media specialist

- Casual game developer

- Mobile application developer

Read through the description of each career, including the links within each description. Choose one career that you are interested in pursuing, research the skills and qualifications it requires, and then write a one-page paper on what you found. Here are some other helpful websites you might like to use in your research:

- Digital Jobs of the Future: Integrated Digital Media Specialist: http://www.s2m.com.au/news/2009/11/26/digital-jobs-of-the-future-integrated-digital-media-specialist/?403

- Cloud Computing Jobs: http://cloudczar.com/

- Top Careers for College Graduates: Casual Game Development: http://www.examiner.com/x-11055-San-Diego-College-Life-Examiner~y2009m5d27-Top-careers-for-college-graduates-Casual -Game-Development

- How to Become a Mobile Application Developer: http://www.ehow.com/how_5638517_become-mobile-application-developer.html

- Mobile App Development: So Many Choices, So Few Guarantees: http://www.linuxinsider.com/story/70128.html?wlc=1277823391

- 20 Websites to Help You Master User Interface Design: http://sixrevisions.com/usabilityaccessibility/20-websites-to-help-you-master-user-interface-design/