This is “Consumer Behavior: How People Make Buying Decisions”, chapter 3 from the book Marketing Principles (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 3 Consumer Behavior: How People Make Buying Decisions

Why do you buy the things you do? How did you decide to go to the college you’re attending? Where do like to shop and when? Do your friends shop at the same places or different places?

Marketing professionals want to know the answers to these questions. They know that once they do have those answers, they will have a much better chance of creating and communicating about products that you and people like you will want to buy. That’s what the study of consumer behavior is all about. Consumer behaviorThe study of when, where, and how people buy things and then dispose of them. considers the many reasons why—personal, situational, psychological, and social—people shop for products, buy and use them, and then dispose of them.

Companies spend billions of dollars annually studying what makes consumers “tick.” Although you might not like it, Google, AOL, and Yahoo! monitor your Web patterns—the sites you search, that is. The companies that pay for search advertisingAdvertising that appears on the Web pages pulled up when online searches are conducted., or ads that appear on the Web pages you pull up after doing an online search, want to find out what kind of things you’re interested in. Doing so allows these companies to send you popup ads and coupons you might actually be interested in instead of ads and coupons for products such as Depends or Viagra.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in conjunction with a large retail center, has tracked consumers in retail establishments to see when and where they tended to dwell, or stop to look at merchandise. How was it done? By tracking the position of the consumers’ mobile phones as the phones automatically transmitted signals to cellular towers. MIT found that when people’s “dwell times” increased, sales increased, too.“The Way the Brain Buys,” Economist, December 20, 2009, 105–7.

Researchers have even looked at people’s brains by having them lie in scanners and asking them questions about different products. What people say about the products is then compared to what their brains scans show—that is, what they are really thinking. Scanning people’s brains for marketing purposes might sound nutty. But maybe not when you consider the fact is that eight out of ten new consumer products fail, even when they are test marketed. Could it be that what people say about potentially new products and what they think about them are different? Marketing professionals want to find out.“The Way the Brain Buys,” Economist, December 20, 2009, 105–7.

Studying people’s buying habits isn’t just for big companies, though. Even small businesses and entrepreneurs can study the behavior of their customers with great success. For example, by figuring out what zip codes their customers are in, a business might determine where to locate an additional store. Customer surveys and other studies can also help explain why buyers purchased what they did and what their experiences were with a business. Even small businesses such as restaurants use coupon codes. For example, coupons sent out in newspapers are given one code. Those sent out via the Internet are given another. Then when the coupons are redeemed, the restaurants can tell which marketing avenues are having the biggest effect on their sales.

Figure 3.1

Tony Hsieh, the chief executive of the shoe company Zappos.com, reportedly has thirty thousand followers on Twitter and his Zappos blog. Dell has begun making millions on Twitter by providing followers with exclusive deals, outlet offers, and product updates. To see the top users of Twitter, go to http://www.twitterholic.com.

© Zappos.com, Inc.

Some businesses, including a growing number of startups, are using blogs and social networking Web sites to gather information about their customers at a low cost. For example, Proper Cloth, a company based in New York, has a site on the social networking site Facebook. Whenever the company posts a new bulletin or photos of its clothes, all its Facebook “fans” automatically receive the information on their own Facebook pages. “We want to hear what our customers have to say,” says Joseph Skerritt, the young MBA graduate who founded Proper Cloth. “It’s useful to us and lets our customers feel connected to Proper Cloth.”Rebecca Knight, “Custom-made for E-tail Success,” Financial Times, March 18, 2009, 10. Skerritt also writes a blog for the company. Twitter and podcasts that can be downloaded from iTunes are two other ways companies are amplifying the “word of mouth” about their products.Rebecca Knight, “Custom-made for E-tail Success,” Financial Times, March 18, 2009, 10.

3.1 The Consumer’s Decision-Making Process

Learning Objectives

- Understand what the stages of the buying process are.

- Distinguish between low-involvement buying decisions and high-involvement buying decisions.

You’ve been a consumer with purchasing power for much longer than you probably realize—since the first time you were asked which cereal or toy you wanted. Over the years, you’ve developed a systematic way you choose among alternatives, even if you aren’t aware of it. Other consumers follow a similar process. The first part of this chapter looks at this process. The second part looks at the situational, psychological, and other factors that affect what, when, and how people buy what they do.

Keep in mind, however, that different people, no matter how similar they are, make different purchasing decisions. You might be very interested in purchasing a Smart Car. But your best friend might want to buy a Ford 150 truck. Marketing professionals understand this. They don’t have unlimited budgets that allow them to advertise in all types of media to all types of people, so what they try to do is figure out trends among consumers. Doing so helps them reach the people most likely to buy their products in the most cost effective way possible.

Stages in the Buying Process

Figure 3.2 "Stages in the Consumer’s Purchasing Process" outlines the buying stages consumers go through. At any given time, you’re probably in some sort of buying stage. You’re thinking about the different types of things you want or need to eventually buy, how you are going to find the best ones at the best price, and where and how will you buy them. Meanwhile, there are other products you have already purchased that you’re evaluating. Some might be better than others. Will you discard them, and if so, how? Then what will you buy? Where does that process start?

Figure 3.2 Stages in the Consumer’s Purchasing Process

Stage 1. Need Recognition

Perhaps you’re planning to backpack around the country after you graduate, but you don’t have a particularly good backpack. Marketers often try to stimulate consumers into realizing they have a need for a product. Do you think it’s a coincidence that Gatorade, Powerade, and other beverage makers locate their machines in gymnasiums so you see them after a long, tiring workout? Previews at movie theaters are another example. How many times have you have heard about a movie and had no interest in it—until you saw the preview? Afterward, you felt like had to see it.

Stage 2. Search for Information

Maybe you have owned several backpacks and know what you like and don’t like about them. Or, there might be a particular brand that you’ve purchased in the past that you liked and want to purchase in the future. This is a great position for the company that owns the brand to be in—something firms strive for. Why? Because it often means you will limit your search and simply buy their brand again.

If what you already know about backpacks doesn’t provide you with enough information, you’ll probably continue to gather information from various sources. Frequently people ask friends, family, and neighbors about their experiences with products. Magazines such as Consumer Reports or Backpacker Magazine might also help you.

Internet shopping sites such as Amazon.com have become a common source of information about products. Epinions.com is an example of consumer-generated review site. The site offers product ratings, buying tips, and price information. Amazon.com also offers product reviews written by consumers. People prefer “independent” sources such as this when they are looking for product information. However, they also often consult nonneutral sources of information, such advertisements, brochures, company Web sites, and salespeople.

Stage 3. Product Evaluation

Obviously, there are hundreds of different backpacks available to choose from. It’s not possible for you to examine all of them. (In fact, good salespeople and marketing professionals know that providing you with too many choices can be so overwhelming, you might not buy anything at all.) Consequently, you develop what’s called evaluative criteria to help you narrow down your choices.

Evaluative criteriaCertain characteristics of products consumers consider when they are making buying decisions. are certain characteristics that are important to you such as the price of the backpack, the size, the number of compartments, and color. Some of these characteristics are more important than others. For example, the size of the backpack and the price might be more important to you than the color—unless, say, the color is hot pink and you hate pink.

Figure 3.3

Osprey backpacks are known for their durability. The company has a special design and quality control center, and Osprey’s salespeople annually take a “canyon testing” trip to see how well the company’s products perform.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Marketing professionals want to convince you that the evaluative criteria you are considering reflect the strengths of their products. For example, you might not have thought about the weight or durability of the backpack you want to buy. However, a backpack manufacturer such as Osprey might remind you through magazine ads, packaging information, and its Web site that you should pay attention to these features—features that happen to be key selling points of its backpacks.

Stage 4. Product Choice and Purchase

Stage 4 is the point at which you decide what backpack to purchase. However, in addition to the backpack, you are probably also making other decisions at this stage, including where and how to purchase the backpack and on what terms. Maybe the backpack was cheaper at one store than another, but the salesperson there was rude. Or maybe you decide to order online because you’re too busy to go to the mall. Other decisions, particularly those related to big ticket items, are made at this point. If you’re buying a high-definition television, you might look for a store that will offer you credit or a warranty.

Stage 5. Postpurchase Use and Evaluation

At this point in the process you decide whether the backpack you purchased is everything it was cracked up to be. Hopefully it is. If it’s not, you’re likely to suffer what’s called postpurchase dissonanceA situation in which consumers rethink their decisions after purchasing products and wonder if they made the best decision.. You might call it buyer’s remorse. You want to feel good about your purchase, but you don’t. You begin to wonder whether you should have waited to get a better price, purchased something else, or gathered more information first. Consumers commonly feel this way, which is a problem for sellers. If you don’t feel good about what you’ve purchased from them, you might return the item and never purchase anything from them again. Or, worse yet, you might tell everyone you know how bad the product was.

Companies do various things to try to prevent buyer’s remorse. For smaller items, they might offer a money back guarantee. Or, they might encourage their salespeople to tell you what a great purchase you made. How many times have you heard a salesperson say, “That outfit looks so great on you!”? For larger items, companies might offer a warranty, along with instruction booklets, and a toll-free troubleshooting line to call. Or they might have a salesperson call you to see if you need help with product.

Stage 6. Disposal of the Product

There was a time when neither manufacturers nor consumers thought much about how products got disposed of, so long as people bought them. But that’s changed. How products are being disposed is becoming extremely important to consumers and society in general. Computers and batteries, which leech chemicals into landfills, are a huge problem. Consumers don’t want to degrade the environment if they don’t have to, and companies are becoming more aware of the fact.

Take for example, Crystal Light, a water-based beverage that’s sold in grocery stores. You can buy it in a bottle. However, many people buy a concentrated form of it, put it in reusable pitchers or bottles, and add water. That way, they don’t have to buy and dispose of plastic bottle after plastic bottle, damaging the environment in the process. Windex has done something similar with its window cleaner. Instead of buying new bottles of it all the time, you can purchase a concentrate and add water. You have probably noticed that most grocery stores now sell cloth bags consumers can reuse instead of continually using and discarding of new plastic or paper bags.

Other companies are less concerned about conservation than they are about planned obsolescenceA deliberate effort by companies to make their products obsolete, or unusable, after a period of time.. Planned obsolescence is a deliberate effort by companies to make their products obsolete, or unusable, after a period of time. The goal is to improve a company’s sales by reducing the amount of time between the repeat purchases consumers make of products. When a software developer introduces a new version of product, older versions of it are usually designed to be incompatible with it. For example, not all the formatting features are the same in Microsoft Word 2003 and 2007. Sometimes documents do not translate properly when opened in the newer version. Consequently, you will be more inclined to upgrade to the new version so you can open all Word documents you receive.

Products that are disposable are another way in which firms have managed to reduce the amount of time between purchases. Disposable lighters are an example. Do you know anyone today that owns a nondisposable lighter? Believe it or not, prior to the 1960s, scarcely anyone could have imagined using a cheap disposable lighter. There are many more disposable products today than there were in years past—including everything from bottled water and individually wrapped snacks to single-use eye drops and cell phones.

Figure 3.4

Disposable lighters came into vogue in the United States in the 1960s. You probably don’t own a cool, nondisposable lighter like one of these, but you don’t have to bother refilling it with lighter fluid either.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Low-Involvement versus High-Involvement Buying Decisions

Consumers don’t necessarily go through all the buying stages when they’re considering purchasing product. You have probably thought about many products you want or need but never did much more than that. At other times, you’ve probably looked at dozens of products, compared them, and then decided not to purchase any one of them. At yet other times, you skip stages 1 through 3 and buy products on impulse. As Nike would put, you “just do it.” Perhaps you see a magazine with Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt on the cover and buy it on the spot simply because you want it. Purchasing a product with no planning or forethought is called impulse buyingPurchases that occurs with no planning or forethought..

Impulse buying brings up a concept called level of involvement—that is, how personally important or interested you are in consuming a product. For example, you might see a roll of tape at a check-out stand and remember you need one. Or you might see a bag of chips and realize you’re hungry. These are items you need, but they are low-involvement products. Low-involvement productsProducts that carry a low risk of failure and/or have a low price tag for a specific individual or group making the decision. aren’t necessarily purchased on impulse, although they can be. Low-involvement products are, however, inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if she makes a mistake by purchasing them.

Consumers often engage in routine response behaviorWhen consumers make automatic purchase decisions based on limited information or information they have gathered in the past. when they buy low-involvement products—that is, they make automatic purchase decisions based on limited information or information they have gathered in the past. For example, if you always order a Diet Coke at lunch, you’re engaging in routine response behavior. You may not even think about other drink options at lunch because your routine is to order a Diet Coke, and you simply do it. If you’re served a Diet Coke at lunchtime, and it’s flat, oh well. It’s not the end of the world.

By contrast, high-involvement productsProducts that carry a high price tag or high level of risk to the individual or group making the decision. carry a high risk to buyers if they fail, are complex, or have high price tags. A car, a house, and an insurance policy are examples. These items are not purchased often. Buyers don’t engage in routine response behavior when purchasing high-involvement products. Instead, consumers engage in what’s called extended problem solvingPurchasing decisions in which a consumer gathers a significant amount of information before making a decision., where they spend a lot of time comparing the features of the products, prices, warrantees, and so forth.

High-involvement products can cause buyers a great deal of postpurchase dissonance if they are unsure about their purchases. Companies that sell high-involvement products are aware of that postpurchase dissonance can be a problem. Frequently, they try to offer consumers a lot of information about their products, including why they are superior to competing brands and how they won’t let the consumer down. Salespeople are typically utilized to do a lot of customer “hand-holding.”

Figure 3.5

Allstate’s “You’re in Good Hands” advertisements are designed to convince consumers that the insurance company won’t let them down.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Limited problem solving falls somewhere in the middle. Consumers engage in limited problem solvingPurchasing decisions made based on consideration of some outside information. when they already have some information about a good or service but continue to search for a bit more information. The backpack you’re looking to buy is an example. You’re going to spend at least some time looking for one that’s decent because you don’t want it to fall apart while you’re traveling and dump everything you’ve packed on a hiking trail. You might do a little research online and come to a decision relatively quickly. You might consider the choices available at your favorite retail outlet but not look at every backpack at every outlet before making a decision. Or, you might rely on the advice of a person you know who’s knowledgeable about backpacks. In some way you shorten the decision-making process.

Brand names can be very important regardless of the consumer’s level of purchasing involvement. Consider a low- versus high-involvement product—say, purchasing a tube of toothpaste versus a new car. You might routinely buy your favorite brand of toothpaste, not thinking much about the purchase (engage in routine response behavior), but not be willing to switch to another brand either. Having a brand you like saves you “search time” and eliminates the evaluation period because you know what you’re getting.

When it comes to the car, you might engage in extensive problem solving but, again, only be willing to consider a certain brands or brands. For example, in the 1970s, American-made cars had such a poor reputation for quality, buyers joked that a car that’s “not Jap [Japanese made] is crap.” The quality of American cars is very good today, but you get the picture. If it’s a high-involvement product you’re purchasing, a good brand name is probably going to be very important to you. That’s why the makers of high-involvement products can’t become complacent about the value of their brands.

Video Clip

1970s American Cars

(click to see video)Today, Lexus is the automotive brand that experiences the most customer loyalty. For a humorous, tongue-in-cheek look at why the brand reputation of American carmakers suffered in the 1970s, check out this clip.

Key Takeaway

Consumer behavior looks at the many reasons why people buy things and later dispose of them. Consumers go through distinct buying phases when they purchases products: (1) realizing the need or want something, (2) searching for information about the item, (3) evaluating different products, (4) choosing a product and purchasing it, (5) using and evaluating the product after the purchase, and (6) disposing of the product. A consumer’s level of involvement is how interested he or she is in buying and consuming a product. Low-involvement products are usually inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if she makes a mistake by purchasing them. High-involvement products carry a high risk to the buyer if they fail, are complex, or have high price tags. Limited-involvement products fall somewhere in between.

Review Questions

- What is consumer behavior? Why do companies study it?

- What stages do people go through in the buying process?

- How do low-involvement products differ from high-involvement products in terms of the risks their buyers face? Name some products in each category that you’ve recently purchased.

3.2 Situational Factors That Affect People’s Buying Behavior

Learning Objectives

- Describe the situational factors that affect what consumers buy and when.

- Explain what marketing professionals can do to make situational factors work to their advantage.

Situational influences are temporary conditions that affect how buyers behave—whether they actually buy your product, buy additional products, or buy nothing at all from you. They include things like physical factors, social factors, time factors, the reason for the buyer’s purchase, and the buyer’s mood. You have undoubtedly been affected by all these factors at one time or another. Because businesses very much want to try to control these factors, let’s now look at them in more detail.

The Consumer’s Physical Situation

Have you ever been in a department story and couldn’t find your way out? No, you aren’t necessarily directionally challenged. Marketing professionals take physical factors such as a store’s design and layout into account when they are designing their facilities. Presumably, the longer you wander around a facility, the more you will spend. Grocery stores frequently place bread and milk products on the opposite ends of the stores because people often need both types of products. To buy both, they have to walk around an entire store, which of course, is loaded with other items they might see and purchase.

Store locations are another example of a physical factor. Starbucks has done a good job in terms of locating its stores. It has the process down to a science; you can scarcely drive a few miles down the road without passing a Starbucks. You can also buy cups of Starbucks coffee at many grocery stores and in airports—virtually any place where there is foot traffic.

Physical factors like these—the ones over which firms have control—are called atmosphericsThe physical aspects of the selling environment retailers try to control.. In addition to store locations, they include the music played at stores, the lighting, temperature, and even the smells you experience. Perhaps you’ve visited the office of an apartment complex and noticed how great it looked and even smelled. It’s no coincidence. The managers of the complex were trying to get you to stay for a while and have a look at their facilities. Research shows that “strategic fragrancing” results in customers staying in stores longer, buying more, and leaving with better impression of the quality of stores’ services and products. Mirrors near hotel elevators are another example. Hotel operators have found that when people are busy looking at themselves in the mirrors, they don’t feel like they are waiting as long for their elevators.Patricia Moore, “Smells Sell,” NZ Business, February 2008, 26–27.

Not all physical factors are under a company’s control, however. Take weather, for example. Rain and other types of weather can be a boon to some companies, like umbrella makers such as London Fog, but a problem for others. Beach resorts, outdoor concert venues, and golf courses suffer when the weather is rainy. So do a lot of retail organizations—restaurants, clothing stores, and automobile dealers. Who wants to shop for a car in the rain or snow?

Firms often attempt to deal with adverse physical factors such as bad weather by making their products more attractive during unattractive times. For example, many resorts offer consumers discounts to travel to beach locations during hurricane season. Having an online presence is another way to cope with weather-related problems. What could be more comfortable than shopping at home? If it’s too cold and windy to drive to the GAP, REI, or Abercrombie & Fitch, you can buy these companies’ products online. You can shop online for cars, too, and many restaurants take orders online and deliver.

Crowding is another situational factor. Have you ever left a store and not purchased anything because it was just too crowded? Some studies have shown that consumers feel better about retailers who attempt to prevent overcrowding in their stores. However, other studies have shown that to a certain extent, crowding can have a positive impact on a person’s buying experience. The phenomenon is often referred to as “herd behavior.”

If people are lined up to buy something, you want to know why. Should you get in line to buy it too? Herd behavior helped drive up the price of houses in the mid-2000s before the prices for them rapidly fell. Unfortunately, herd behavior has also led to the deaths of people. In 2008, a store employee was trampled to death by an early morning crowd rushing into a Walmart to snap up holiday bargains.

To some extent, how people react to crowding depends on their personal tolerance levels. Which rock concert would you rather attend: A sold-out concert in which the crowd is having a rocking good time? Or a half-sold-out concert where you can perhaps move to a seat closer to the stage and not have to stand in line at the restrooms?Carol J. Gaumer and William C. Leif, “Social Facilitation: Affect and Application in Consumer Buying Situations,” Journal of Food Products Marketing 11, no. 1 (2005): 75–82.

The Consumer’s Social Situation

The social situation you’re in can significantly affect what you will buy, how much of it, and when. Perhaps you have seen Girl Scouts selling cookies outside grocery stores and other retail establishments and purchased nothing from them. But what if your neighbor’s daughter is selling the cookies? Are you going to turn her down, or be a friendly neighbor and buy a box (or two)?

Video Clip

Thin Mints, Anyone?

(click to see video)Are you going to turn down this cute Girl Scout’s cookies? What if she’s your neighbor’s daughter? Pass the milk, please!

Companies like Avon and Tupperware that sell their products at parties understand that the social situation you’re in makes a difference. When you’re at a Tupperware party a friend is having, you don’t want to disappoint her by not buying anything. Plus, everyone at the party will think you’re cheap.

Certain social situations can also make you less willing to buy products. You might spend quite a bit of money each month eating at fast-food restaurants like McDonald’s and Subway. But suppose you’ve got a hot first date? Where do you take your date? Some people might take a first date to Subway, but that first date might also be the last. Other people would perhaps choose a restaurant that’s more upscale. Likewise, if you have turned down a drink or dessert on a date because you were worried about what the person you were with might have thought, your consumption was affected by your social situation.Anna S. Matilla and Jochen Wirtz, “The Role of Store Environmental Stimulation and Social Factors on Impulse Purchasing,” Journal of Services Marketing 22, no. 7 (2008): 562–67.

The Consumer’s Time Situation

The time of day, the time of year, and how much time consumers feel like they have to shop also affects what they buy. Researchers have even discovered whether someone is a “morning person” or “evening person” affects shopping patterns. Seven-Eleven Japan is a company that’s extremely in tune to physical factors such as time and how it affects buyers. The company’s point-of-sale systems at its checkout counters monitor what is selling well and when, and stores are restocked with those items immediately—sometimes via motorcycle deliveries that zip in and out of traffic along Japan’s crowded streets. The goal is to get the products on the shelves when and where consumers want them. Seven-Eleven Japan also knows that, like Americans, its customers are “time starved.” Shoppers can pay their utility bills, local taxes, and insurance or pension premiums at Seven-Eleven Japan stores, and even make photocopies.Allan Bird, “Retail Industry,” Encyclopedia of Japanese Business and Management (London: Routledge, 2002), 399–400.

Companies worldwide are aware of people’s lack of time and are finding ways to accommodate them. Some doctors’ offices offer drive-through shots for patients who are in a hurry and for elderly patients who find it difficult to get out of their cars. Tickets.com allows companies to sell tickets by sending them to customers’ mobile phones when they call in. The phones’ displays are then read by barcode scanners when the ticket purchasers arrive at the events they’re attending. Likewise, if you need customer service from Amazon.com, there’s no need to wait on hold on the telephone. If you have an account with Amazon, you just click a button on the company’s Web site and an Amazon representative calls you immediately.

The Reason for the Consumer’s Purchase

The reason you are shopping also affects the amount of time you will spend shopping. Are you making an emergency purchase? Are you shopping for a gift? In recent years, emergency clinics have sprung up in strip malls all over the country. Convenience is one reason. The other is sheer necessity. If you cut yourself and you are bleeding badly, you’re probably not going to shop around much to find the best clinic to go to. You will go to the one that’s closest to you.

What about shopping for a gift? Purchasing a gift might not be an emergency situation, but you might not want to spend much time shopping for it either. Gift certificates have been a popular way to purchase for years. But now you can purchase them as cards at your corner grocery store. By contrast, suppose you need to buy an engagement ring. Sure, you could buy one online in a jiffy, but you probably wouldn’t, because it’s a high-involvement product. What if it were a fake? How would you know until after you purchased it? What if your significant other turned you down and you had to return the ring? How hard would it be to get back online and return the ring?Jacob Hornik and Giulia Miniero, “Synchrony Effects on Customers’ Responses and Behaviors,” International Journal of Research in Marketing 26, no. 1 (2009): 34–40.

The Consumer’s Mood

Have you ever felt like going on a shopping spree? At other times wild horses couldn’t drag you to a mall. People’s moods temporarily affect their spending patterns. Some people enjoy shopping. It’s entertaining for them. At the extreme are compulsive spenders who get a temporary “high” from spending.

A sour mood can spoil a consumer’s desire to shop. The crash of the U.S. stock market in 2008 left many people feeling poorer, leading to a dramatic downturn in consumer spending. Penny pinching came into vogue, and conspicuous spending was out. Costco and Walmart experienced heightened sales of their low-cost Kirkland Signature and Great Value brands as consumers scrimped.“Wal-Mart Unveils Plans for Own-Label Revamp,” Financial Times, March 17, 2009, 15.

Saks Fifth Avenue wasn’t so lucky. Its annual release of spring fashions usually leads to a feeding frenzy among shoppers, but spring 2009 was different. “We’ve definitely seen a drop-off of this idea of shopping for entertainment,” says Kimberly Grabel, Saks Fifth Avenue’s senior vice president of marketing.Stephanie Rosenbloom (New York Times News Service), “Where Have All the Shoppers Gone?” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 18, 2009, 5E.

To get buyers in the shopping mood, companies resorted to different measures. The upscale retailer Neiman Marcus began introducing more midpriced brands. By studying customer’s loyalty cards, the French hypermarket Carrefour hoped to find ways to get its customers to purchase nonfood items that have higher profit margins.

The glum mood wasn’t bad for all businesses though. Discounters like Half-Priced books saw their sales surge. So did seed sellers as people began planting their own gardens. Finally, those products you see being hawked on television? Aqua Globes, Snuggies, and Ped Eggs? Their sales were the best ever. Apparently, consumers too broke to go to on vacation or shop at Saks were instead watching television and treating themselves to the products.Alyson Ward, “Products of Our Time,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 7, 2009, 1E.

Key Takeaway

Situational influences are temporary conditions that affect how buyers behave. They include physical factors such as a store’s buying locations, layout, music, lighting, and even smells. Companies try to make the physical factors in which consumers shop as favorable as possible. If they can’t, they utilize other tactics such as discounts. The consumer’s social situation, time situation, the reason for their purchases, and their moods also affect their buying behavior.

Review Questions

- Why and how does the social situation the consumer is in play a role in behavior?

- Outline the types of physical factors companies try to affect and how they go about it.

- What social situations have you been in that affected what you purchased?

- What types of moods and time situations are likely to affect people’s buying behavior?

3.3 Personal Factors That Affect People’s Buying Behavior

Learning Objectives

- Explain how a person’s self-concept and ideal self affects what he or she buys.

- Describe how companies market products to people based on their genders, life stages, and ages.

- Explain how looking at the lifestyles of consumers helps firms understand what they want to purchase.

The Consumer’s Personality

PersonalityAn individual’s disposition as other people see it. describes a person’s disposition as other people see it. The following are the “Big Five” personality traits that psychologists discuss frequently:

- Openness. How open you are to new experiences.

- Conscientiousness. How diligent you are.

- Extraversion. How outgoing or shy you are.

- Agreeableness. How easy you are to get along with.

- Neuroticism. How prone you are to negative mental states.

The question marketing professionals want answered is do the traits predict people’s purchasing behavior? Can companies successfully target certain products at people based on their personalities? And how do you find out what personalities they have? Are the extraverts you know wild spenders and the introverts you know penny pinchers? Maybe not.

The link between people’s personalities and their buying behavior is somewhat unclear, but market researchers continue to study it. For example, some studies have shown that “sensation seekers,” or people who exhibit extremely high levels of openness, are more likely to respond well to advertising that’s violent and graphic. The practical problem for firms is figuring out “who’s who” in terms of their personalities.

The Consumer’s Self-Concept

Marketers have had better luck linking people’s self-concept to their buying behavior. Your self-conceptHow a person sees himself or herself. is how you see yourself—be it positive or negative. Your ideal selfHow a person would like to view himself or herself. is how you would like to see yourself—whether it’s prettier, more popular, more eco-conscious, or more “goth.”

Marketing researchers believe people buy products to enhance how they feel about themselves—to get themselves closer to their ideal selves, in other words. The slogan “Be All That You Can Be,” which for years was used by the U.S. Army to recruit soldiers, is an attempt to appeal to the self-concept. Presumably, by joining the U.S. Army, you will become a better version of yourself, which will, in turn, improve your life. Many beauty products and cosmetic procedures are advertised in a way that’s supposed to appeal to the ideal selves people are searching for. All of us want products that improve our lives.

The Consumer’s Gender

Everyone knows that men and women buy different products. Physiologically speaking, they simply need different product—different underwear, shoes, toiletries, and a host of other products.Cheryl B. Ward and Tran Thuhang, “Consumer Gifting Behaviors: One for You, One for Me?” Services Marketing Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2007): 1–17. Men and women also shop differently. One study by Resource Interactive, a technology research firm, found that when shopping online, men prefer sites with lots of pictures of products; women prefer to see products online in lifestyle context—say, a lamp in a living room. Women are also twice as likely as men to use viewing tools such as the zoom and rotate buttons and links that allow them to change the color of products.

In general, men have a different attitude about shopping than women do. You know the old stereotypes: Men see what they a want and buy it, but women “shop ‘til they drop.” There’s some truth to the stereotypes. Otherwise, you wouldn’t see so many advertisements directed at one sex or the other—beer commercials that air on ESPN and commercials for household products that air on Lifetime. In fact, women influence fully two-thirds of all household product purchases, whereas men buy about three-quarters of all alcoholic beverages.Genevieve Schmitt, “Hunters and Gatherers,” Dealernews 44, no. 8 (2008): 72. The article references the 2006 Behavioral Tracking Study by Miller Brewing Company.

Video Clip

What Women Want versus What Men Want

(click to see video)Check out this Heineken commercial which highlights the differences between “what women want” and “what men want” when it comes to products.

The shopping differences between men and women seem to be changing, though. For example, younger, well-educated men are less likely to believe grocery shopping is a woman’s job. They would also be more inclined to bargain shop and use coupons if the coupons were properly targeted at them.Jeanne Hill and Susan K. Harmon, “Male Gender Role Beliefs, Coupon Use and Bargain Hunting,” Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 11, no. 2 (2007): 107–21. One survey found that approximately 45 percent of married men actually like shopping and consider it relaxing.

Figure 3.6

Marketing to men is big business. Some advertising agencies specialize in advertisements designed specifically to appeal to male consumers.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Many businesses today are taking greater pains to figure out “what men want.” Products such as face toners and body washes for men, such as the Axe brand, are a relatively new phenomenon. So are hair salons such as the Men’s Zone and Weldon Barber. Some advertising agencies specialize in advertising directed at men. Keep in mind that there are also many items targeted toward women that weren’t in the past, including products such as kayaks and mountain bikes.

The Consumer’s Age and Stage of Life

You have probably noticed that the things you buy have changed as you age. When you were a child, the last thing you probably wanted as a gift was clothing. As you became a teen, however, cool clothes probably became a bigger priority. Don’t look now, but depending on the stage of life you’re currently in, diapers and wrinkle cream might be just around the corner.

Companies understand that people buy different things based on their ages and life stages. Aging baby boomers are a huge market that companies are trying to tap. Ford and other car companies have created “aging suits” for young employees to wear when they’re designing automobiles.“Designing Cars for the Elderly: A Design Story,” http://www.businessweek.com/globalbiz/content/may2008/gb2008056_154197.htm (accessed April 13, 2012). The suit simulates the restricted mobility and vision people experience as they get older. Car designers can then figure out how to configure the automobiles to better meet the needs of these consumers.

Lisa Rudes Sandel, the founder of Not Your Daughter’s Jeans (NYDJ), created a multimillion-dollar business by designing jeans for baby boomers with womanly bodies. Since its launch seven years ago, NYDJ has become the largest domestic manufacturer of women’s jeans under $100. “The truth is,” Rudes Sandel says, “I’ve never forgotten that woman I’ve been aiming for since day one.” Sandel “speaks to” every one of her customers via a note tucked into each pair of jean that reads, “NYDJ (Not Your Daughter’s Jeans) cannot be held responsible for any positive consequence that may arise due to your fabulous appearance when wearing the Tummy Tuck jeans. You can thank me later.”Sarah Saffian, “Dreamers: The Making of Not Your Daughter’s Jeans,” Reader’s Digest, March 2009, 53–55.

Figure 3.7

You’re only as old as you feel—and the things you buy.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Your chronological ageA person’s age in years., or actual age in years, is one thing. Your cognitive ageThe age a buyer perceives himself or herself to be., or how old you perceive yourself to be, is another. In other words, how old do you really feel? A person’s cognitive age affects the activities one engages in and sparks interests consistent with the person’s perceived age.Benny Barak and Steven Gould, “Alternative Age Measures: A Research Agenda,” in Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 12, ed. Elizabeth C. Hirschman and Morris B. Holbrook (Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 1985), 53–58. Cognitive age is a significant predictor of consumer behaviors, including people’s dining out, watching television, going to bars and dance clubs, playing computer games, and shopping.Benny Barak and Steven Gould, “Alternative Age Measures: A Research Agenda,” in Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 12, ed. Elizabeth C. Hirschman and Morris B. Holbrook (Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 1985), 53–58. How old people “feel” they are has important implications for marketing professionals. For example, companies have found that many “aged” consumers don’t take kindly to products that feature “old folks.” The consumers can’t identify with them because they see themselves as being younger. We will discuss more about the various age groups and how marketing professionals try to target them in Chapter 5 "Market Segmenting, Targeting, and Positioning".

The Consumer’s Lifestyle

At the beginning of the chapter, we explained that two consumers (say, you and your best friend) can be similar in age, personality, gender, and so on but still purchase very different products. If you have ever watched the television show Wife Swap, you can see that despite people’s similarities (e.g., being middle-class Americans who are married with children), their lifestyles can differ radically.

To better understand consumers and connect with them, companies have begun looking more closely at consumers’ lifestyles. This often includes asking consumers to fill out extensive questionnaires or conducting in-depth interviews with them. The questionnaires go beyond asking people about the products they like, where they live, and what sex they are. Instead, researchers ask people what they do—that is, how they spend their time and what their priorities, values, and general outlooks on the world are. Where do they go other than work? Who do they like to talk to? What do they talk about? Researchers hired by Procter & Gamble have gone so far as to follow women around for weeks as they shop, run errands, and socialize with one another.Robert Berner, “Detergent Can Be So Much More,” BusinessWeek, May 1, 2006, 66–68. Other companies have paid people to keep a daily journal of their activities and routines.

Audio Clip

Interview with Joy Mead

http://app.wistia.com/embed/medias/45f9c7fa67Joy Mead is an associate director of marketing for Procter & Gamble. Listen to this audio clip to learn about the approach Procter & Gamble takes to understand customers.

A number of research organizations examine lifestyle and psychographic characteristics of consumers. PsychographicsMeasuring the attitudes, values, lifestyles, and opinions of consumers using demographics. combines the lifestyle traits of consumers (for example, whether they are single or married, wealthy or poor, well-educated or high school dropouts) and their personality styles with an analysis of their attitudes, activities, and values to determine groups of consumers with similar characteristics. We will talk more about psychographics and what companies do to develop further insight into what consumers want in Chapter 5 "Market Segmenting, Targeting, and Positioning".

Key Takeaway

Your personality describes your disposition as other people see it. Market researchers believe people buy products to enhance how they feel about themselves. Your gender also affects what you buy and how you shop. Women shop differently than men. However, there’s some evidence that this is changing. Younger men and women are beginning to shop more alike. People buy different things based on their ages and life stages. A person’s cognitive age is how old he “feels” himself to be. To further understand consumers and connect with them, companies have begun looking more closely at their lifestyles (what they do, how they spend their time, what their priorities and values are, and how they see the world).

Review Questions

- Explain how someone’s personality differs from his or her self-concept. How does the person’s ideal self come into play in a consumer-behavior context?

- Describe the buying patterns women exhibit versus men.

- Why are companies interested in consumers’ cognitive ages?

- What are some of the consumer lifestyle factors firms examine?

3.4 Psychological Factors That Affect People’s Buying Behavior

Learning Objectives

- Explain how Maslow’s hierarchy of needs works.

- Outline the additional psychological factors that affect people’s buying behavior.

Motivation

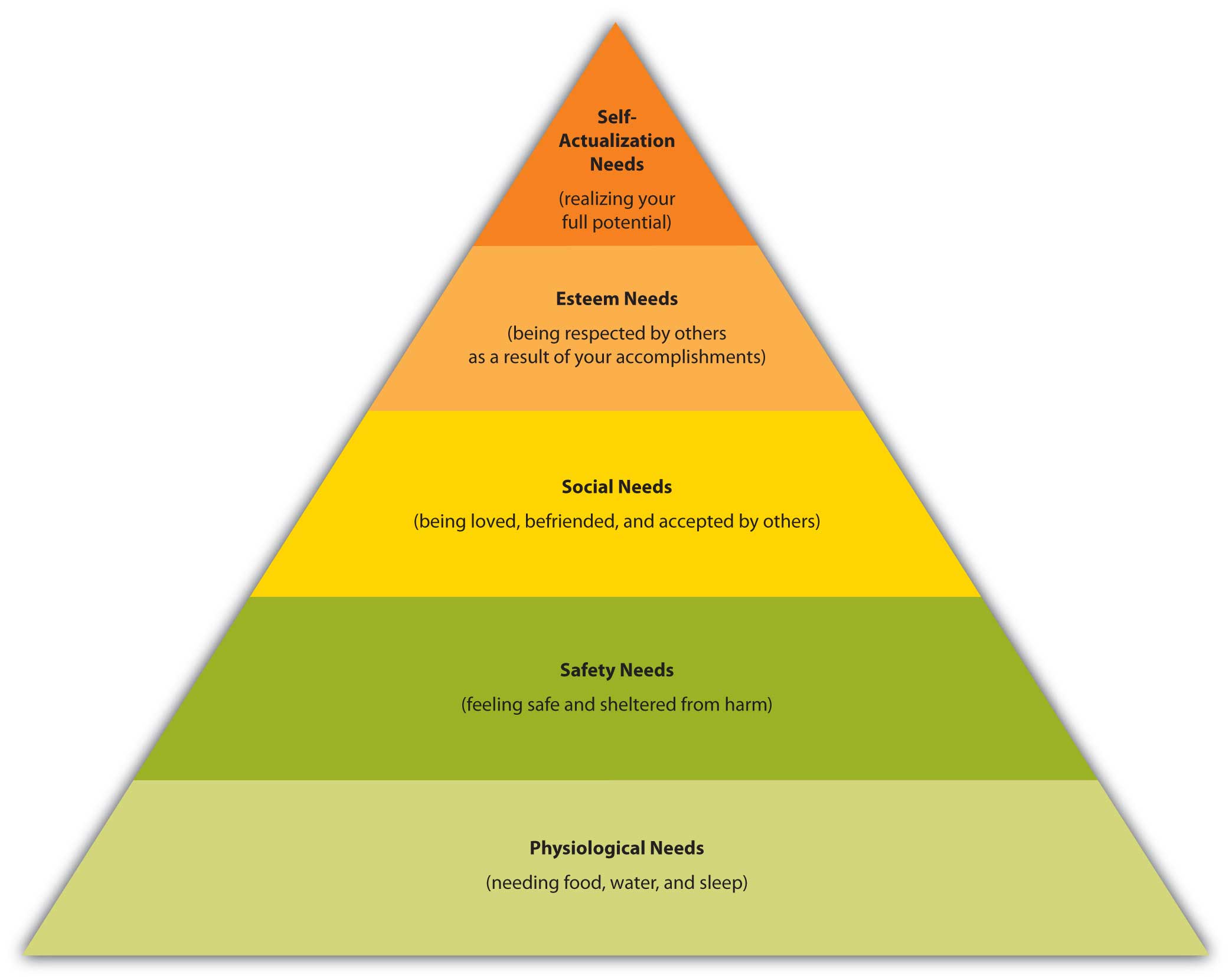

MotivationThe inward drive people have to get what they need. is the inward drive we have to get what we need. In the mid-1900s, Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist, developed the hierarchy of needs shown in Figure 3.8 "Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs".

Figure 3.8 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow theorized that people have to fulfill their basic needs—like the need for food, water, and sleep—before they can begin fulfilling higher-level needs. Have you ever gone shopping when you were tired or hungry? Even if you were shopping for something that would make you envy of your friends (maybe a new car) you probably wanted to sleep or eat even worse. (Forget the car. Just give me a nap and a candy bar.)

People’s needs can be recurring, such as the physiological need for hunger. You eat breakfast and are hungry at lunchtime and then again in the evening. Other needs tend to be enduring, such as the need for shelter, clothing, and safety. Still other needs arise at different points in time in a person’s life. For example, during grade school and high school, your social needs probably rose to the forefront. You wanted to have friends and get a date. Perhaps this prompted you to buy certain types of clothing or electronic devices. After high school, you began thinking about how people would view you in your “station” in life, so you decided to pay for college and get a professional degree, thereby fulfilling your need for esteem. If you’re lucky, at some point you will realize Maslow’s state of self-actualization: You will believe you have become the person in life that you feel you were meant to be.

Marketing professionals understand Maslow’s hierarchy. Take the need for people to feel secure and safe. Following the economic crisis that began in 2008, the sales of new automobiles dropped sharply virtually everywhere around the world—except the sales of Hyundai vehicles. Hyundai ran an ad campaign that assured car buyers they could return their vehicles if they couldn’t make the payments on them without damaging their credit. Other carmakers began offering similar programs after they saw how successful Hyundai had been.

Likewise, banks began offering “worry-free” mortgages to ease the minds of would-be homebuyers. For a fee of about $500, First Mortgage Corp., a Texas-based bank, offered to make a homeowner’s mortgage payment for six months if he or she got laid off.Andrea Jares, “New Programs Are Taking Worries from Home Buying,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 7, 2010, 1C–2C.

The Consumer’s Perception

PerceptionHow people interpret the world around them. is how you interpret the world around you and make sense of it in your brain. You do so via stimuli that affect your different senses—sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. How you combine these senses also makes a difference. For example, in one study, consumers were blindfolded and asked to drink a new brand of clear beer. Most of them said the product tasted like regular beer. However, when the blindfolds came off and they drank the beer, many of them described it as “watery” tasting.Laura Ries, In the Boardroom: Why Left-Brained Management and Right-Brain Marketing Don’t See Eye-to-Eye (New York: HarperCollins, 2009).

Using different types of stimuli, marketing professionals try to make you more perceptive to their products whether you need them or not. It’s not an easy job. Consumers today are bombarded with all types of marketing from every angle—television, radio, magazines, the Internet, and even bathroom walls. It’s been estimated that the average consumer is exposed to about three thousand advertisements per day.Kalle Lasn, Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1999). Consumers are also multitasking more today than in the past. They are surfing the Internet, watching television, and checking their cell phones for text messages simultaneously. All day, every day, we are receiving information. Some, but not all, of it makes it into our brains.

Have you ever read or thought about something and then started noticing ads and information about it popping up everywhere? That’s because your perception of it had become heightened. Many people are more perceptive to advertisements for products they need. Selective perceptionThe process whereby a person filters information based on how relevant it is to them. is the process of filtering out information based on how relevant it is to you. It’s been described as a “suit of armor” that helps you filter out information you don’t need. At other times, people forget information, even if it’s quite relevant to them, which is called selective retentionThe process whereby a person retains information based on how well it matches their values and beliefs.. Usually the information contradicts the person’s belief. A longtime chain smoker who forgets much of the information communicated during an antismoking commercial is an example.

To be sure their advertising messages get through to you, companies use repetition. How tired of iPhone commercials were you before they tapered off the tube? How often do you see the same commercial aired during a single television show?

Video Clip

A Parody of an iPhone Commercial

(click to see video)Check out this parody on Apple’s iPhone commercial.

Using surprising stimuli is also a technique. Sometimes this is called shock advertisingAdvertising designed to startle people so as to get their attention.. The clothing makers Benetton and Calvin Klein are probably best known for their shocking advertising. Calvin Klein sparked an uproar when it featured scantily clad prepubescent teens in its ads. There’s evidence that shock advertising actually works, though. One study found that shocking content increased attention, benefited memory, and positively influenced behavior among a group of university students.Darren W. Dahl, Kristina D. Frankenberger, and Rajesh V. Manchanda, “Does It Pay to Shock? Reactions to Shocking and Nonshocking Advertising Content among University Students,” Journal of Advertising Research 43, no. 3 (2003): 268–80.

Subliminal advertisingAdvertising that is not apparent to consumers but is thought to be perceived subconsciously by them. is the opposite of shock advertising. It involves exposing consumers to marketing stimuli—photos, ads, message, and so forth—by stealthily embedding them in movies, ads, and other media. For example, the words Drink Coca-Cola might be flashed for a millisecond on a movie screen. Consumers were thought to perceive the information subconsciously, and it would make them buy products. Keep in mind that today it’s common to see brands such as Coke being consumed in movies and television programs, but there’s nothing subliminal about it. Coke and other companies often pay to have their products in the shows.

The general public became aware of subliminal advertising in the 1960s. Many people considered the practice to be subversive, and in 1974, the Federal Communications Commission condemned it. Its effectiveness is somewhat sketchy, in any case. It didn’t help that much of the original research on it, conducted in the 1950s by a market researcher who was trying to drum up business for his market research firm, was fabricated.Cynthia Crossen, “For a Time in the ’50s, A Huckster Fanned Fears of Ad ‘Hypnosis,’” Wall Street Journal, November 5, 2007, eastern edition, B1.

People are still fascinated by subliminal advertising, however. To create “buzz” about the television show The Mole in 2008, ABC began hyping it by airing short commercials composed of just a few frames. If you blinked, you missed it. Some television stations actually called ABC to figure out what was going on. One-second ads were later rolled out to movie theaters.Josef Adalian, “ABC Hopes ‘Mole’ Isn’t Just a Blip,” Television Week, June 2, 2008, 3.

Even if your marketing effort reaches consumers and they retain it, different consumers can perceive it differently. Show two people the same product and you’ll get two different perceptions of it. One man sees Pledge, an outstanding furniture polish, while another sees a can of spray no different from any other furniture polish. One woman sees a luxurious Gucci purse, and the other sees an overpriced bag to hold keys and makeup.James Chartrand, “Why Targeting Selective Perception Captures Immediate Attention,” http://www.copyblogger.com/selective-perception (accessed October 14, 2009). A couple of frames about The Mole might make you want to see the television show. However, your friend might see the ad, find it stupid, and never tune in to watch the show.

Learning

LearningThe process by which consumers change their behavior after they gain information or experience with a product. refers to the process by which consumers change their behavior after they gain information or experience a product. It’s the reason you don’t buy a crummy product twice. Learning doesn’t just affect what you buy, however. It affects how you shop. People with limited experience about a product or brand generally seek out more information about it than people who have used it before.

Companies try to get consumers to learn about their products in different ways. Car dealerships offer test drives. Pharmaceutical reps leave behind lots of free items at doctor’s offices with medication names and logos written all over them—pens, coffee cups, magnets, and so on. Free samples of products that come in the mail or are delivered with newspapers are another example. To promote its new line of coffees, McDonald’s offered customers free samples to try.

Another kind of learning is operant conditioningA type of behavior that’s repeated when it’s rewarded., which is what occurs when researchers are able to get a mouse to run through a maze for a piece cheese or a dog to salivate just by ringing a bell. Companies engage in operant conditioning by rewarding consumers, too. The prizes that come in Cracker Jacks and with McDonald’s Happy Meals are examples. The rewards cause consumers to want to repeat their purchasing behaviors. Other rewards include free tans offered with gym memberships, punch cards that give you a free Subway sandwich after a certain number of purchases, and free car washes when you fill up your car with a tank of gas.

Consumer’s Attitude

Attitudes“Mental positions” or emotional feelings people have about products, services, companies, ideas, issues, or institutions. are “mental positions” or emotional feelings people have about products, services, companies, ideas, issues, or institutions.“Dictionary of Marketing Terms,” http://www.allbusiness.com/glossaries/marketing/4941810-1.html (accessed October 14, 2009). Attitudes tend to be enduring, and because they are based on people’s values and beliefs, they are hard to change. That doesn’t stop sellers from trying, though. They want people to have positive rather than negative feelings about their offerings. A few years ago, KFC began running ads to the effect that fried chicken was healthy—until the U.S. Federal Trade Commission told the company to stop. Wendy’s slogan to the effect that its products are “way better than fast food” is another example. Fast food has a negative connotation, so Wendy’s is trying to get consumers to think about its offerings as being better.

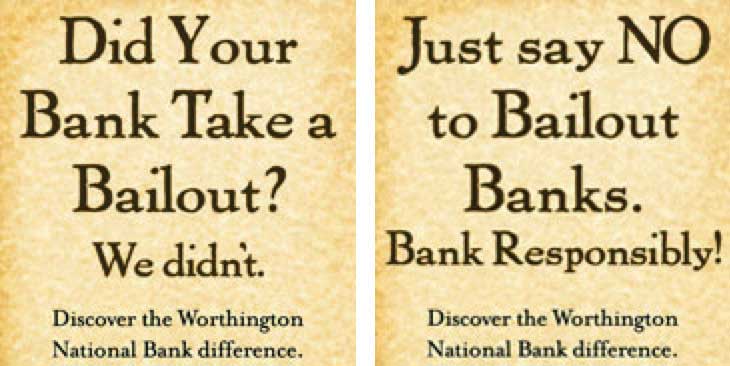

A good example of a shift in the attitudes of consumers relates to banks. The taxpayer-paid government bailouts of big banks that began in 2008 provoked the wrath of Americans, creating an opportunity for small banks not involved in the credit derivates and subprime mortgage mess. The Worthington National Bank, a small bank in Fort Worth, Texas, ran billboards reading: “Did Your Bank Take a Bailout? We didn’t.” Another read: “Just Say NO to Bailout Banks. Bank Responsibly!” The Worthington Bank received tens of millions in new deposits soon after running these campaigns.Joe Mantone, “Banking on TARP Stigma,” SNLi, March 16, 2009, http://www.snl.com/Interactivex/article.aspx?CdId=A-9218440-12642 (accessed October 14, 2009).

Figure 3.9

Worthington National, a small Texas bank, capitalized on people’s bad attitudes toward big banks that accepted bailouts from the government in 2008–2009. After running billboards with this message, the bank received millions of dollars in new deposits.

© WorthingtonBank.com

Key Takeaway

Psychologist Abraham Maslow theorized that people have to fulfill their basic needs—like the need for food, water, and sleep—before they can begin fulfilling higher-level needs. Perception is how you interpret the world around you and make sense of it in your brain. To be sure their advertising messages get through to you, companies often resort to repetition. Shocking advertising and subliminal advertising are two other methods. Learning is the process by which consumers change their behavior after they gain information about or experience with a product. Consumers’ attitudes are the “mental positions” people take based on their values and beliefs. Attitudes tend to be enduring and are often difficult for companies to change.

Review Questions

- How does Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs help marketing professionals?

- How does the process of perception work and how can companies use it to their advantage in their marketing?

- What types of learning do companies try to get consumers to engage in?

3.5 Societal Factors That Affect People’s Buying Behavior

Learning Objectives

- Explain why the culture, subcultures, social classes, and families consumers belong to affect their buying behavior.

- Describe what reference groups and opinion leaders are.

Situational factors—the weather, time of day, where you are, who you are with, and your mood—influence what you buy, but only on a temporary basis. So do personal factors, such as your gender, as well as psychological factors, such as your self-concept. Societal factors are a bit different. They are more outward. They depend on the world around you and how it works.

The Consumer’s Culture

CultureThe shared beliefs, customs, behaviors, and attitudes that characterize a society used to cope with their world and with one another. refers to the shared beliefs, customs, behaviors, and attitudes that characterize a society. Your culture prescribes the way in which you should live. As a result, it has a huge effect on the things you purchase. For example, in Beirut, Lebanon, women can often be seen wearing miniskirts. If you’re a woman in Afghanistan wearing a miniskirt, however, you could face bodily harm or death. In Afghanistan women generally wear burqas, which cover them completely from head to toe. Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, women must wear what’s called an abaya, or long black garment. Interestingly, abayas have become big business in recent years. They come in many styles, cuts, and fabrics. Some are encrusted with jewels and cost thousands of dollars.

To read about the fashions women in Muslim countries wear, check out the following article: http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1210781,00.html.

Even cultures that share many of the same values as the United States can be quite different from the United States in many ways. Following the meltdown of the financial markets in 2008, countries around the world were pressed by the United States to engage in deficit spending so as to stimulate the worldwide economy. But the plan was a hard sell both to German politicians and the German people in general. Most Germans don’t own credit cards, and running up a lot of debt is something people in that culture generally don’t do. Companies such as Visa and MasterCard and businesses that offer consumers credit to purchase items with high ticket prices have to deal with factors such as these.

The Consumer’s Subculture(s)

A subcultureA group of people within a culture who are different from the dominant culture but have something in common with one another, such as common interests, vocations or jobs, religions, ethnic backgrounds, or sexual orientations. is a group of people within a culture who are different from the dominant culture but have something in common with one another—common interests, vocations or jobs, religions, ethnic backgrounds, sexual orientations, and so forth. The fastest-growing subculture in the United States consists of people of Hispanic origin, followed by Asian Americans, and blacks. The purchasing power of U.S. Hispanics is growing by leaps and bounds. By 2010 it is expected to reach more than $1 trillion.Larry Watrous, “Illegals: The New N-Word in America,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 16, 2009, 9B. This is a lucrative market that companies are working to attract. Home Depot has launched a Spanish version of its Web site. Walmart is in the process of converting some of its Neighborhood Markets into stores designed to appeal to Hispanics. The Supermarcado de Walmart stores are located in Hispanic neighborhoods and feature elements such as cafés serving Latino pastries and coffee and full meat and fish counters.Jonathan Birchall, “Wal-Mart Looks to Hispanic Market in Expansion Drive,” Financial Times, March 13, 2009, 18.

Figure 3.10

Care to join the subculture of the “Otherkin”? Otherkins are primarily Internet users who believe they are reincarnations of mythological or legendary creatures—angels, demons, vampires—you name it. To read more about the Otherkins and seven other bizarre subcultures, visit http://www.oddee.com/item_96676.aspx.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Marketing products based the ethnicity of consumers is useful. However, it could become harder to do in the future because the boundaries between ethnic groups are blurring. For example, many people today view themselves as multiracial. (Golfer Tiger Woods is a notable example.) Also, keep in mind that ethnic and racial subcultures are not the only subcultures marketing professionals look at. As we have indicated, subcultures can develop in response to people’s interest. You have probably heard of the hip-hop subculture, people who in engage in extreme types of sports such as helicopter skiing, or people who play the fantasy game Dungeons and Dragons. The people in these groups have certain interests and exhibit certain behaviors that allow marketing professionals design specific products for them.

The Consumer’s Social Class

A social classA group of people who have the same social, economic, or educational status in society. is a group of people who have the same social, economic, or educational status in society.Princeton University, “WordNet,” http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=social+class&sub=Search+WordNet&o2=&o0=1&o7=&o5=&o1 =1&o6=&o4=&o3=&h= (accessed October 14, 2009). To some degree, consumers in the same social class exhibit similar purchasing behavior. Have you ever been surprised to find out that someone you knew who was wealthy drove a beat-up old car or wore old clothes and shoes? If so, it was because the person, given his or her social class, was behaving “out of the norm” in terms of what you thought his or her purchasing behavior should be.

Table 3.1 "Social Classes and Buying Patterns: An Example" shows seven classes of American consumers along with the types of car brands they might buy. Keep in mind that the U.S. market is just a fraction of the world market. As we explained in Chapter 2 "Strategic Planning", to sustain their products, companies often launch their products in other parts of the world. The rise of the middle class in India and China is creating opportunities for many companies to successfully do this. For example, China has begun to overtake the United States as the world’s largest auto market.“More Cars Sold in China than in January,” France 24, February 10, 2009, http://www.france24.com/en/20090210-more-cars-sold-china-us-january-auto-market (accessed October 14, 2009).

Table 3.1 Social Classes and Buying Patterns: An Example

| Class | Type of Car | Definition of Class |

|---|---|---|

| Upper-Upper Class | Rolls-Royce | People with inherited wealth and aristocratic names (the Kennedys, Rothschilds, Windsors, etc.) |

| Lower-Upper Class | Mercedes | Professionals such as CEOs, doctors, and lawyers |

| Upper-Middle Class | Lexus | College graduates and managers |

| Middle Class | Toyota | Both white-collar and blue-collar workers |

| Working Class | Pontiac | Blue-collar workers |

| Lower but Not the Lowest | Used Vehicle | People who are working but not on welfare |

| Lowest Class | No vehicle | People on welfare |

The makers of upscale brands in particular walk a fine line in terms of marketing to customers. On the one hand, they want their customer bases to be as large as possible. This is especially tempting in a recession when luxury buyers are harder to come by. On the other hand, if the companies create products the middle class can better afford, they risk “cheapening” their brands. That’s why, for example, Smart Cars, which are made by BMW, don’t have the BMW label on them. For a time, Tiffany’s sold a cheaper line of silver jewelry to a lot of customers. However, the company later worried that its reputation was being tarnished by the line. Keep in mind that a product’s price is to some extent determined by supply and demand. Luxury brands therefore try to keep the supply of their products in check so their prices remain high.

Figure 3.11

The whiskey brand Johnnie Walker has managed to expand its market share without cheapening the brand by producing a few lower-priced versions of the whiskey and putting them in bottles with different labels.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Some companies have managed to capture market share by introducing “lower echelon” brands without damaging their luxury brands. Johnnie Walker is an example. The company’s whiskeys come in bottles with red, green, blue, black, and gold labels. The blue label is the company’s best product. Every blue-label bottle has a serial number and is sold in a silk-lined box, accompanied by a certificate of authenticity.“Johnnie Walker,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnnie_Walker (accessed October 14, 2009).

Reference Groups and Opinion Leaders

Of course, you probably know people who aren’t wealthy but who still drive a Mercedes or other upscale vehicle. That’s because consumers have reference groups. Reference groupsGroups a consumer identifies with and wants to join. are groups a consumer identifies with and wants to join. If you have ever dreamed of being a professional player of basketball or another sport, you have a reference group. Marketing professionals are aware of this. That’s why, for example, Nike hires celebrities such as Michael Jordan to pitch the company’s products.

Opinion leadersPeople with expertise certain areas. Consumers respect these people and often ask their opinions before they buy goods and services. are people with expertise in certain areas. Consumers respect these people and often ask their opinions before they buy goods and services. An information technology specialist with a great deal of knowledge about computer brands is an example. These people’s purchases often lie at the forefront of leading trends. For example, the IT specialist we mentioned is probably a person who has the latest and greatest tech products, and his opinion of them is likely to carry more weight with you than any sort of advertisement.

Today’s companies are using different techniques to reach opinion leaders. Network analysis using special software is one way of doing so. Orgnet.com has developed software for this purpose. Orgnet’s software doesn’t mine sites like Facebook and LinkedIn, though. Instead, it’s based on sophisticated techniques that unearthed the links between Al Qaeda terrorists. Explains Valdis Krebs, the company’s founder: “Pharmaceutical firms want to identify who the key opinion leaders are. They don’t want to sell a new drug to everyone. They want to sell to the 60 key oncologists.”Anita Campbell, “Marketing to Opinion Leaders,” Small Business Trends, June 28, 2004, http://smallbiztrends.com/2004/06/marketing-to-opinion-leaders.html (accessed October 13, 2009). As you can probably tell from this chapter, exploring the frontiers of people’s buying patterns is a fascinating and constantly evolving field.

The Consumer’s Family

Most market researchers consider a person’s family to be one of the biggest determiners of buying behavior. Like it or not, you are more like your parents than you think, at least in terms of your consumption patterns. The fact is that many of the things you buy and don’t buy are a result of what your parents do and do not buy. The soap you grew up using, toothpaste your parents bought and used, and even the “brand” of politics you lean toward (Democratic or Republican) are examples of the products you are likely to favor as an adult.

Family buying behavior has been researched extensively. Companies are also interested in which family members have the most influence over certain purchases. Children have a great deal of influence over many household purchases. For example, in 2003 nearly half (47 percent) of nine- to seventeen-year-olds were asked by parents to go online to find out about products or services, compared to 37 percent in 2001. IKEA used this knowledge to design their showrooms. The children’s bedrooms feature fun beds with appealing comforters so children will be prompted to identify and ask for what they want.“Teen Market Profile,” Mediamark Research, 2003, http://www.magazine.org/content/files/teenprofile04.pdf (accessed December 4, 2009).

Marketing to children has come under increasing scrutiny. Some critics accuse companies of deliberating manipulating children to nag their parents for certain products. For example, even though tickets for Hannah Montana concerts ranged from hundreds to thousands of dollars, the concerts often still sold out. However, as one writer put it, exploiting “pester power” is not always ultimately in the long-term interests of advertisers if it alienates kids’ parents.Ray Waddell, “Miley Strikes Back,” Billboard, June 27, 2009, 7–8.

Key Takeaway

Culture prescribes the way in which you should live and affects the things you purchase. A subculture is a group of people within a culture who are different from the dominant culture but have something in common with one another—common interests, vocations or jobs, religions, ethnic backgrounds, sexual orientations, and so forth. To some degree, consumers in the same social class exhibit similar purchasing behavior. Most market researchers consider a person’s family to be one of the biggest determiners of buying behavior. Reference groups are groups that a consumer identifies with and wants to join. Companies often hire celebrities to endorse their products to appeal to people’s reference groups. Opinion leaders are people with expertise in certain areas. Consumers respect these people and often ask their opinions before they buy goods and services.

Review Questions

- Why do people’s cultures affect what they buy?

- How do subcultures differ from cultures? Can you belong to more than one culture or subculture?

- How are companies trying to reach opinion leaders today?

3.6 Discussion Questions and Activities

Discussion Questions

- Why do people in different cultures buy different products? Discuss with your class the types of vehicles you have seen other countries. Why are they different, and how do they better meet buyers’ needs in those countries? What types of cars do you think should be sold in the United States today?

- What is your opinion of companies like Google that gather information about your browsing patterns? What advantages and drawbacks does this pose for consumers? If you were a business owner, what kinds of information would you gather on your customers and how would you use it?

- Are there any areas in which you consider yourself an opinion leader? What are they?

- What purchasing decisions have you been able to influence in your family and why? Is marketing to children a good idea? If not, what if one of your competitors were successfully do so? Would it change your opinion?

- How do you determine what is distinctive about different groups? What distinguishes one group from other groups?

- Name some products that have led to postpurchase dissonance on your part. Then categorize them as high- or low-involvement products.

- Describe the decision process for impulse purchases at the retail level. Would they be classified as high- or low-involvement purchases?

- How do you think the manufacturers of products sold through infomercials reduce postpurchase dissonance?

- Explain the relationship between extensive, limited, and routine decision making relative to high and low involvement. Identify examples of extensive, limited, and routine decision making based on your personal consumption behavior.

Activities

- Go to http://www.ospreypacks.com and enter the blog site. Does the blog make you more or less inclined to purchase an Osprey backpack?

- Select three advertisements and describe the needs identified by Maslow that each ad addresses.

- Break up into groups and visit an ethnic part of your town that differs from your own ethnicity(ies). Walk around the neighborhood and its stores. What types of marketing and buying differences do you see? Write a report of your findings.

- Using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, identify a list of popular advertising slogans that appeal to each of the five levels.

- Identify how McDonald’s targets both users (primarily children) and buyers (parents, grandparents, etc.). Provide specific examples of strategies used by the fast-food marketer to target both groups. Make it a point to incorporate Happy Meals and Mighty Kids Meals into your discussion.