This is “Buyer Power”, section 7.8 from the book Managerial Economics Principles (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.8 Buyer Power

The bulk of this chapter looked at facets of market power that is possessed and exploited by sellers. However, in markets with a few buyers that individually make a sizeable fraction of total market purchases, buyers can exercise power that will influence the market price and quantity.

The most extreme form of buyer power is when there is a single buyer, called a monopsonyIn a market with a single buyer, the buyer has the power to push the price down to a minimum.. If there is no market power among the sellers, the buyer is in a position to push the price down to the minimum amount needed to induce a seller to produce the last unit. The supply curve for seller designates this price for any given level of quantity. Although the monopsonist could justify purchasing additional units up to the point where the supply curve crosses its demand curve, the monopsonist can usually get a higher value by purchasing a smaller amount at a lower price at another point on the supply curve.

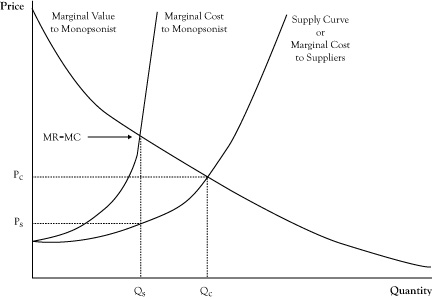

Assuming the monopsonist is not able to discriminate in its purchases and buy each unit at the actual marginal cost of the unit, rather buying all units at the marginal cost of the last unit acquired, the monopsonist is aware that when it agrees to pay a slightly higher price to purchase an additional unit, the new price will apply to all units purchased. As such, the marginal cost of increasing its consumption will be higher than the price charged for an additional unit. The monopsonist will maximize its value gained from the purchases (amount paid plus consumer surplus) at the point where the marginal cost of added consumption equals the marginal value of that additional unit, as reflected in its demand curve. This optimal solution is depicted in Figure 7.2 "Graph Showing the Optimal Quantity and Price for a Monopsonist Relative to the Free Market Equilibrium Price and Quantity", with the quantity QS being the amount it will purchase and price PS being the price it can impose on the sellers. Note, as with the solution with a seller monopoly, the quantity is less than would occur if the market demand curve were the composite of small buyers with no market power. However, the monopsonist price is less than the monopoly price because the monopsonist can force the price down to the supply curve rather than to what a unit is worth on the demand curve.

When there are multiple large buyers, there will be increased competition that will generally result in movement along the supply curve toward the point where it crosses the market demand curve. However, unless these buyers are aggressively competitive, they are likely to pay less than under the perfect competition solution by either cooperating with other buyers to keep prices low or taking other actions intended to keep the other buyers out of the market.

An example of a monopsonist would be an employer in a small town with a single large business, like a mining company in a mountain community. The sellers in this case are the laborers. If laborers have only one place to sell their labor in the community, the employer possesses significant market power that it can use to drive down wages and even change the nature of the service provided by demanding more tiring or dangerous working conditions. When the industrial revolution created strong economies of scale that supported very large firms with strong employer purchasing power, laborers faced a difficult situation of low pay and poor working conditions. One of the reasons for the rise of the labor unions in the United States was as a way of creating power for the laborers by requiring a single transaction between the employer and all laborers represented by the union.

Figure 7.2 Graph Showing the Optimal Quantity and Price for a Monopsonist Relative to the Free Market Equilibrium Price and Quantity