This is “The Role and Nature of Investment”, section 14.1 from the book Macroeconomics Principles (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.1 The Role and Nature of Investment

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the components of the investment spending category of GDP and distinguish between gross and net investment.

- Discuss the relationship between consumption, saving, and investment, and explain the relationship using the production possibilities model.

How important is investment? Consider any job you have ever performed. Your productivity in that job was largely determined by the investment choices that had been made before you began to work. If you worked as a clerk in a store, the equipment used in collecting money from customers affected your productivity. It may have been a simple cash register, or a sophisticated computer terminal that scanned purchases and was linked to the store’s computer, which computed the store’s inventory and did an analysis of the store’s sales as you entered each sale. If you have worked for a lawn maintenance firm, the kind of equipment you had to work with influenced your productivity. You were more productive if you had the latest mulching power lawn mowers than if you struggled with a push mower. Whatever the work you might have done, the kind and quality of capital you had to work with strongly influenced your productivity. And that capital was available because investment choices had provided it.

Investment adds to the nation’s capital stock. We saw in the chapter on economic growth that an increase in capital shifts the aggregate production function outward, increases the demand for labor, and shifts the long-run aggregate supply curve to the right. Investment therefore affects the economy’s potential output and thus its standard of living in the long run.

Investment is a component of aggregate demand. Changes in investment shift the aggregate demand curve and thus change real GDP and the price level in the short run. An increase in investment shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right; a reduction shifts it to the left.

Components of Investment

Additions to the stock of private capital are called Gross Private Domestic Investment (GPDI). GPDI includes four categories of investment:

- Nonresidential Structures. This category of investment includes the construction of business structures such as private office buildings, warehouses, factories, private hospitals and universities, and other structures in which the production of goods and services takes place. A structure is counted as GPDI only during the period in which it is built. It may be sold several times after being built, but such sales are not counted as investment. Recall that investment is part of GDP, and GDP is the value of production in any period, not total sales.

- Nonresidential Equipment and Software. Producers’ equipment includes computers and software, machinery, computers, trucks, cars, and desks, that is, any business equipment that is expected to last more than a year. Equipment and software are counted as investment only in the period in which it is produced.

- Residential Investment. This category includes all forms of residential construction, whether apartment houses or single-family homes, as well as residential equipment such as computers and software.

- Change in Private Inventories. Private inventories are considered part of the nation’s capital stock, because those inventories are used to produce other goods. All private inventories are capital; additions to private inventories are thus investment. When private inventories fall, that is recorded as negative investment.

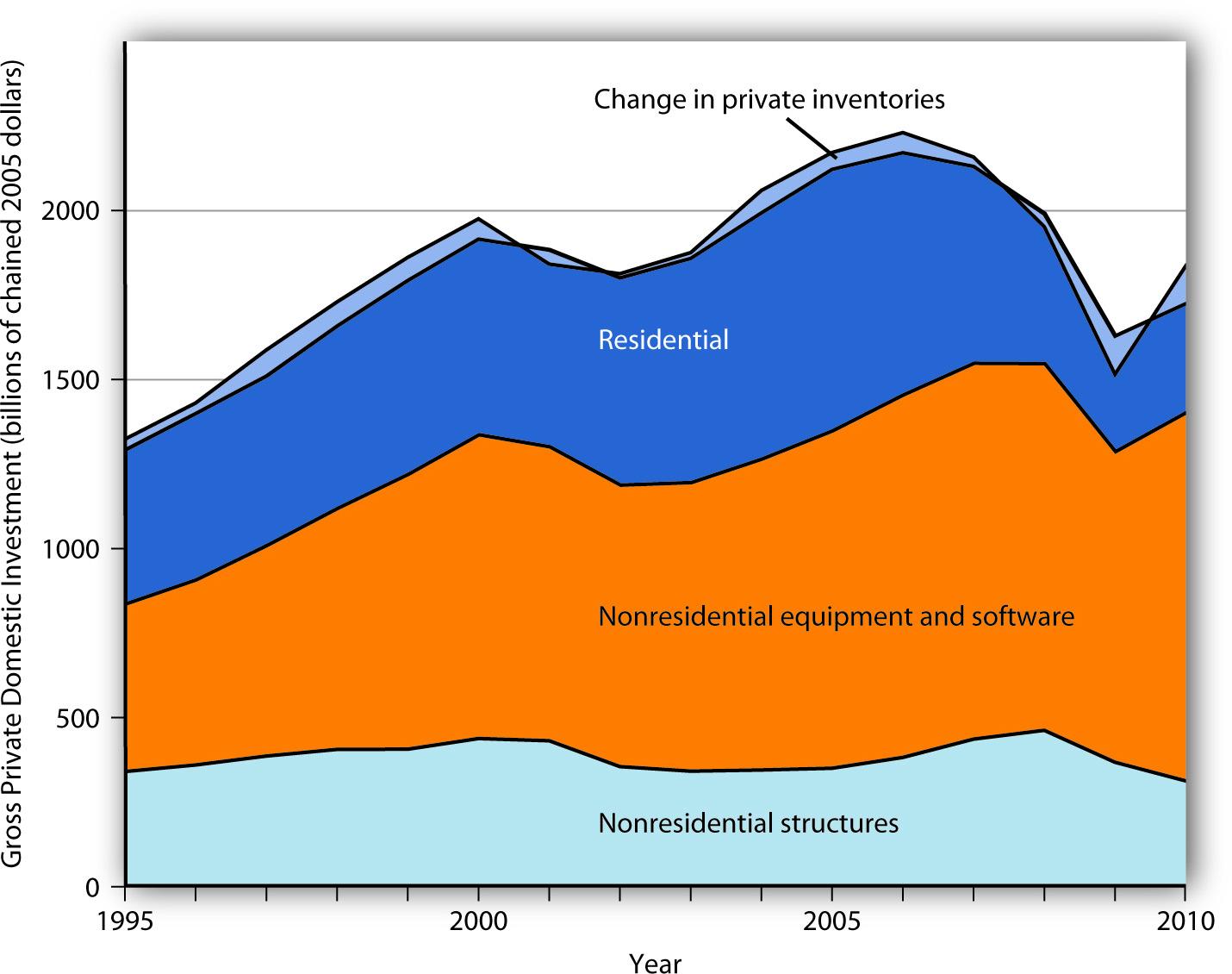

Figure 14.1 "Components of Gross Private Domestic Investment, 1995–2010" shows the components of gross private domestic investment from 1995 through 2010. We see that producers’ equipment and software constitute the largest component of GPDI in the United States. Residential investment was the second largest component of GPDI for most of the period shown but it shrank considerably during the 2007-2009 recession.

Figure 14.1 Components of Gross Private Domestic Investment, 1995–2010

This chart shows the levels of each of the four components of gross private domestic investment from 1990 through the third quarter of 2010. Nonresidential equipment and software is the largest component of GPDI and has shown the most substantial growth over the period.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NIPA Table 1.1.6 (revised November 23, 2010). Data are through the third quarter of 2010.

Gross and Net Investment

As capital is used, some of it wears out or becomes obsolete; it depreciates (the Commerce Department reports depreciation as “consumption of fixed capital”). Investment adds to the capital stock, and depreciation reduces it. Gross investment minus depreciation is net investment. If gross investment is greater than depreciation in any period, then net investment is positive and the capital stock increases. If gross investment is less than depreciation in any period, then net investment is negative and the capital stock declines.

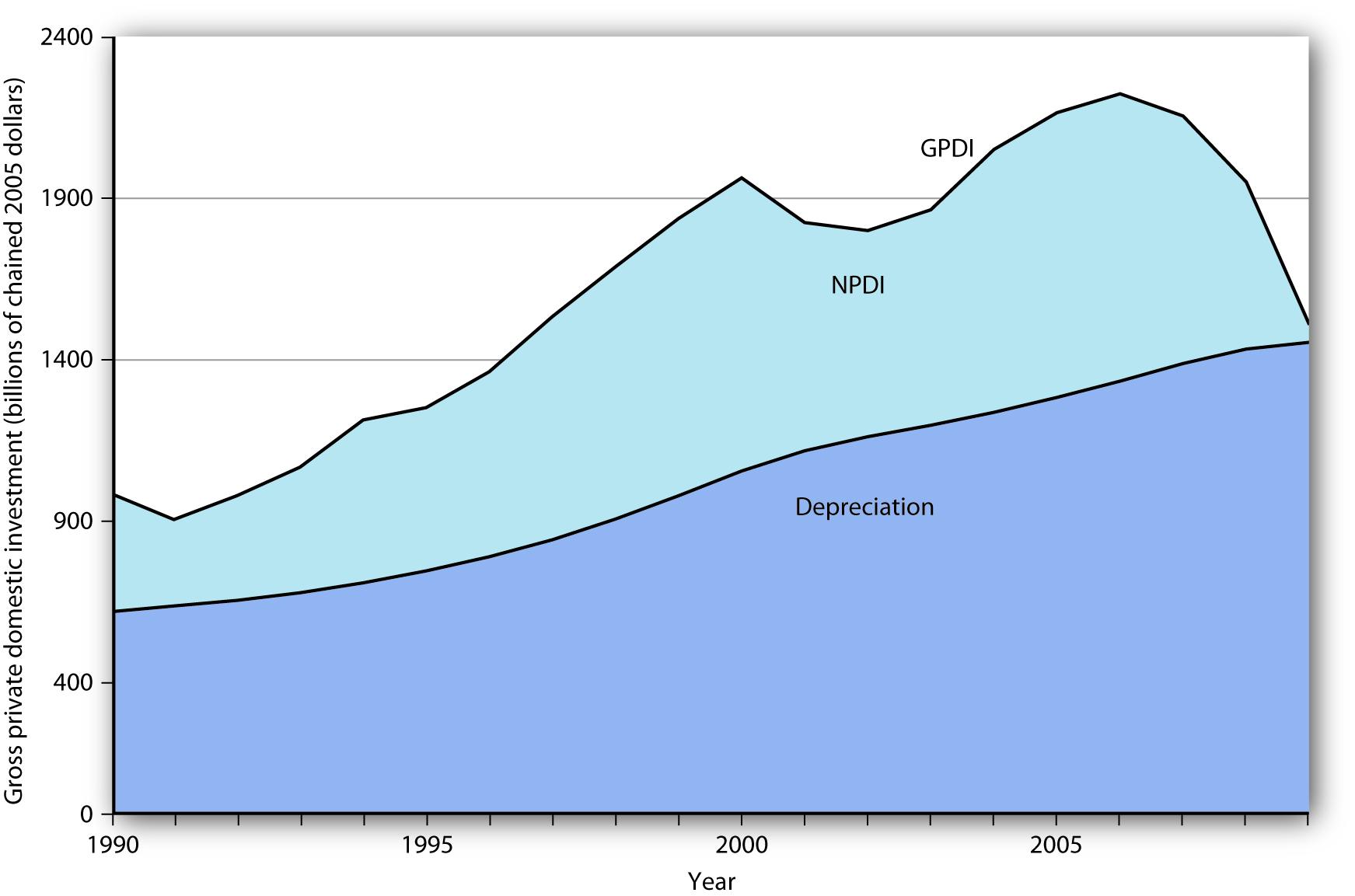

In the official estimates of total output, gross investment (GPDI) minus depreciation equals net private domestic investment (NPDI). The value for NPDI in any period gives the amount by which the privately held stock of physical capital increased during that period.

Figure 14.2 "Gross Private Domestic Investment, Depreciation, and Net Private Domestic Investment, 1990–2009" reports the real values of GPDI, depreciation, and NPDI from 1990 to 2009. We see that the bulk of GPDI replaces capital that has been depreciated. Notice the sharp reductions in NPDI during the recessions of 1990–1991, 2001, and especially 2007 – 2009.

Figure 14.2 Gross Private Domestic Investment, Depreciation, and Net Private Domestic Investment, 1990–2009

The bulk of gross private domestic investment goes to the replacement of capital that has depreciated, as shown by the experience of the past two decades.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NIPA Table 5.2.6 (revised August 5, 2010).

The Volatility of Investment

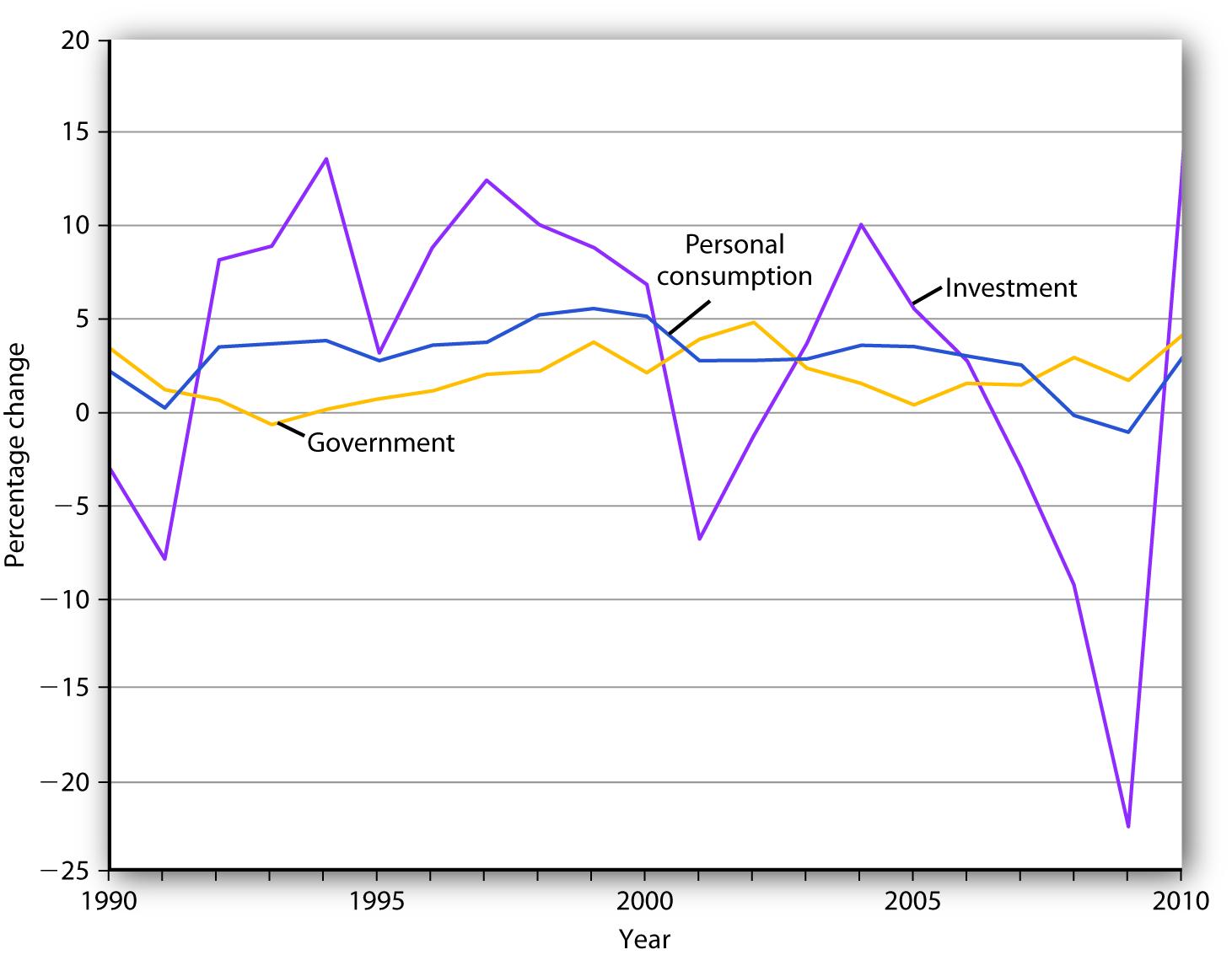

Investment, measured as GPDI, is among the most volatile components of GDP. In percentage terms, year-to-year changes in GPDI are far greater than the year-to-year changes in consumption or government purchases. Net exports are also quite volatile, but they represent a much smaller share of GDP. Figure 14.3 "Changes in Components of Real GDP, 1990–2010" compares annual percentage changes in GPDI, personal consumption, and government purchases. Of course, a dollar change in investment will be a much larger change in percentage terms than a dollar change in consumption, which is the largest component of GDP. But compare investment and government purchases: their shares in GDP are comparable, but investment is clearly more volatile.

Figure 14.3 Changes in Components of Real GDP, 1990–2010

Annual percentage changes in real GPDI have been much greater than annual percentage changes in the real values of personal consumption or government purchases.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NIPA Table 1.1.1 (revised November 23, 2010). Data are through the third quarter of 2010.

Given that the aggregate demand curve shifts by an amount equal to the multiplier times an initial change in investment, the volatility of investment can cause real GDP to fluctuate in the short run. Downturns in investment may trigger recessions.

Investment, Consumption, and Saving

Earlier we used the production possibilities curve to illustrate how choices are made about investment, consumption, and saving. Because such choices are crucial to understanding how investment affects living standards, it will be useful to reexamine them here.

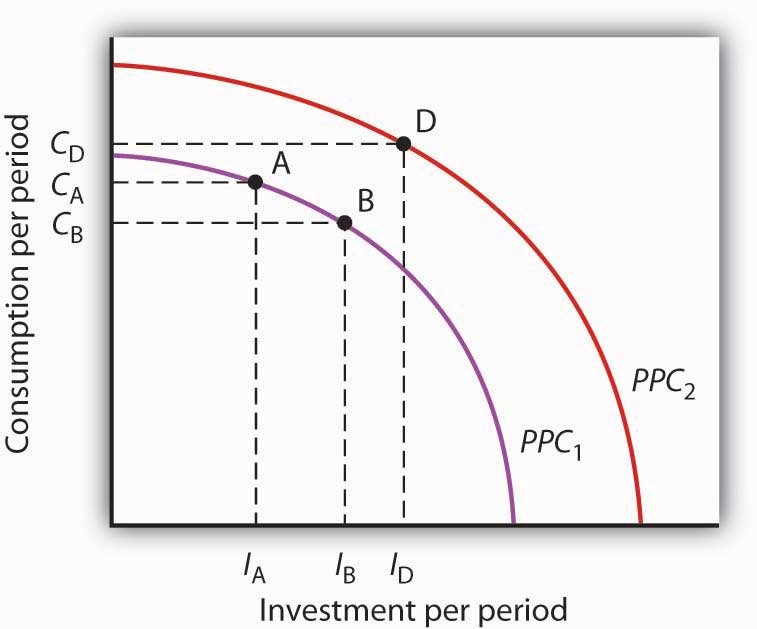

Figure 14.4 "The Choice between Consumption and Investment" shows a production possibilities curve for an economy that can produce two kinds of goods: consumption goods and investment goods. An economy operating at point A on PPC1 is using its factors of production fully and efficiently. It is producing CA units of consumption goods and IA units of investment each period. Suppose that depreciation equals IA, so that the quantity of investment each period is just sufficient to replace depreciated capital; net investment equals zero. If there is no change in the labor force, in natural resources, or in technology, the production possibilities curve will remain fixed at PPC1.

Figure 14.4 The Choice between Consumption and Investment

A society with production possibilities curve PPC1 could choose to produce at point A, producing CA consumption goods and investment of IA. If depreciation equals IA, then net investment is zero, and the production possibilities curve will not shift, assuming no other determinants of the curve change. By cutting its production of consumption goods and increasing investment to IB, however, the society can, over time, shift its production possibilities curve out to PPC2, making it possible to enjoy greater production of consumption goods in the future.

Now suppose decision makers in this economy decide to sacrifice the production of some consumption goods in favor of greater investment. The economy moves to point B on PPC1. Production of consumption goods falls to CB, and investment rises to IB. Assuming depreciation remains IA, net investment is now positive. As the nation’s capital stock increases, the production possibilities curve shifts outward to PPC2. Once that shift occurs, it will be possible to select a point such as D on the new production possibilities curve. At this point, consumption equals CD, and investment equals ID. By sacrificing consumption early on, the society is able to increase both its consumption and investment in the future. That early reduction in consumption requires an increase in saving.

We see that a movement along the production possibilities curve in the direction of the production of more investment goods and fewer consumption goods allows the production of more of both types of goods in the future.

Key Takeaways

- Investment adds to the nation’s capital stock.

- Gross private domestic investment includes the construction of nonresidential structures, the production of equipment and software, private residential construction, and changes in inventories.

- The bulk of gross private domestic investment goes to the replacement of depreciated capital.

- Investment is the most volatile component of GDP.

- Investment represents a choice to postpone consumption—it requires saving.

Try It!

Which of the following would be counted as gross private domestic investment?

- Millie hires a contractor to build a new garage for her home.

- Millie buys a new car for her teenage son.

- Grandpa buys Tommy a savings bond.

- General Motors builds a new automobile assembly plant.

Case in Point: The Reduction of Private Capital in the Depression

Figure 14.5

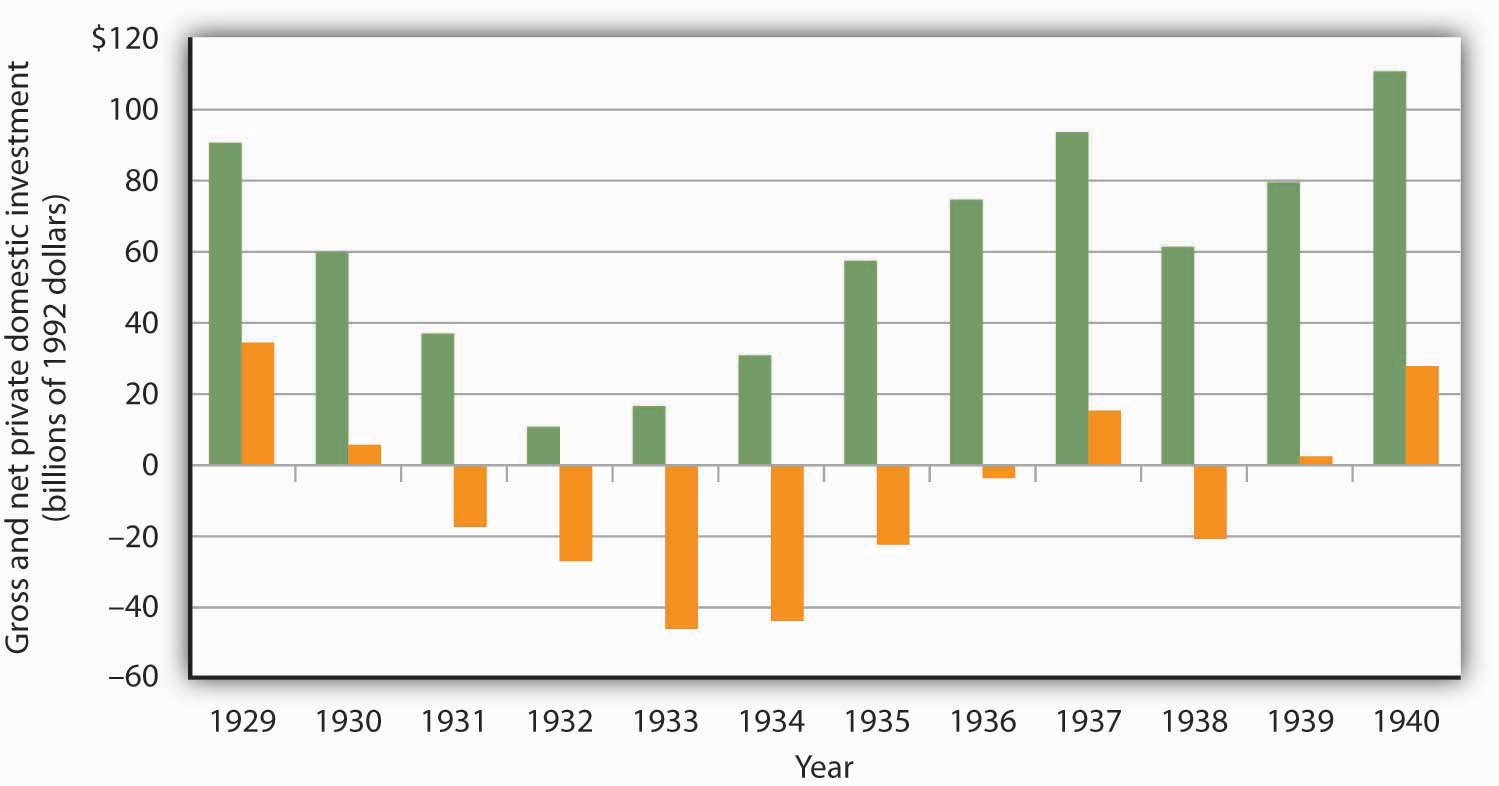

Net private domestic investment (NPDI) has been negative during only two periods in the last 70 years. During one period, World War II, massive defense spending forced cutbacks in private sector spending. (Recall that government investment is not counted as part of net private domestic investment in the official accounts; production of defense capital thus is not reflected in these figures.) The other period in which NPDI was negative was the Great Depression.

Aggregate demand plunged during the first four years of the Depression. As firms cut their output in response to reductions in demand, their need for capital fell as well. They reduced their capital by holding gross private domestic investment below depreciation beginning in 1931. That produced negative net private domestic investment; it remained negative until 1936 and became negative again in 1938. In all, firms reduced the private capital stock by more than $529.5 billion (in 2007 dollars) during the period.

Figure 14.6

Answers to Try It! Problems

- A new garage would be part of residential construction and thus part of GPDI.

- Consumer purchases of cars are part of the consumption component of the GDP accounts and thus not part of GPDI.

- The purchase of a savings bond is an example of a financial investment. Since it is not an addition to the nation’s capital stock, it is not part of GPDI.

- The construction of a new factory is counted in the nonresidential structures component of GPDI.