This is “Choosing a Job”, section 18.1 from the book Individual Finance (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

18.1 Choosing a Job

Learning Objectives

- Describe the macroeconomic factors that affect job markets.

- Describe the microeconomic factors that influence job and career decisions.

- Relate life stages to both microeconomic factors and income needs.

- Describe how relationships between life stages, income needs, and microeconomic factors may affect job and career choices.

A person starting out in the world of work today can expect to change careers—not just jobs—an average of seven times before retiring.U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “National Longitudinal Survey of Youth,” http://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsy79r19sup1.pdf (accessed July 23, 2009). Those career changes may reflect the process of gaining knowledge and skills as you work or changes in industry and economic conditions over several decades of your working life. Knowing this, you cannot base career decisions solely on the circumstances of the moment. However, you also cannot ignore the economics of the job market.

You may have a career in mind but have no idea how to get started, or you may have a job in mind but have no idea where it may lead. If you have a career in mind, you should research its career pathA planned progression of jobs or steps to advance in a profession or career., or sequence of steps that will enable you to advance. Some careers have a well-established career path—for example, careers in law, medicine, teaching, or civil engineering. In other occupations and professions, career paths may not be well defined.

Before you can even focus on a career or a job, however, you need to identify the factors that will affect your decision making process.

Macro Factors of the Job Market

The job market is the market where buyers (employers) and sellers (employees) of labor trade, but it usually refers to the possibilities for employment and its rewards. These will differ by field of employment, types of jobs, and geographic region. The opportunities offered in a job market depend on the supply and demand for jobs, which in turn depend on the need for labor in the broader economy and in a specific industry or geographic area.

The economic cycle can affect the aggregate job market or employment rate. If the economy is in a recession, the economy is producing less, and there is less need for labor, so fewer jobs are available. If the economy is expanding, production and its need for labor are growing.

Typically, a recession or expansion affects different industries in different ways. Some industries are cyclical and some are countercyclical. For example, in a recession, consumer spending is often down, so retail shops and consumer goods manufacturers—in cyclical industries—may be cutting jobs. Meanwhile, more people are continuing their education to improve their skills and the chances of getting a job, which is harder to do in a recession, so jobs in higher education—a countercyclical industry—may be increasing.

For example, it would have been a bad time in the spring of 2009 to think about a career in auto manufacturing in the United States with Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler all announcing massive layoffs, plant closings, and facing bankruptcy. The industry may survive, but it probably won’t be able to rebuild that fast.

Global events such as an outbreak of war, the nationalization of a scarce natural resource, the price of a critical commodity such as crude oil, the collapse of a vital industry, and so on, may also cause changes in the global economy that affect job markets.

Another macroeconomic factor is change in technology, which can open up new fields of employment and make others obsolete. With the advent of digital cameras, for example, even single-use conventional cameras are no longer being manufactured in great quantity, and film developers are not needed as much as they once were. However, there are more jobs for developers of electronic cameras and digital applications for creating images and using digital images in communications channels, such as mobile phones.

Figure 18.2 Workers in the Vacuum Cleaner Factory at Reedsville, West Virginia

Library of Congress, February 1937

A demographic shift also can change entire industries and job opportunities. A historical example, repeated in many developing countries, is the mass migration of rural families to urban centers and factory towns during an industrial revolution. Changes in the composition of a society, such as the average age of the population, also affect job supply and demand. Baby booms create demand for more educators and pediatricians, for example, while aging populations create more demand for goods and services relating to elder care.

Social and cultural factors affect consumer behavior, and consumer preferences can change a job market. Demand for certain kinds of products and services, for example, such as organic foods, hybrid cars, clean energy, and “green” buildings, can increase job opportunities in businesses that address those preferences.

Thus, changes in demand for a product or service will change the need for labor to produce it. On a larger scale, economies typically shift their focus over time as different industries become “growth” industries, that is, the drivers of growth in the economy. In the mid-twentieth century, the United States was a manufacturing economy, driven by the production of durable and consumer goods, especially automobiles. In the 1990s, the computer/internet/tech sector had a larger role in driving growth in the U.S. economy due to technological breakthroughs. Currently, education and health care services are the growing sectors of the economy due to demographic and political changes and needs.U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Industries with the Fastest Growing and Most Rapidly Declining Wage and Salary Employment, 2006–16,” in “Industry Output and Employment Projections to 2016,” Monthly Labor Review, November 2007, http://www.bls.gov/emp/empfastestind.htm (accessed August 5, 2009).

If you are entrepreneurial and intend to be self-employed, your job opportunities may be affected by the ease with which you can start and maintain a business. Ease of entry, in turn, may be affected by macro factors such as the laws and regulations in the state where you intend to do business and the existing competition in the market you are entering.

The labor market is competitive, not just at an individual level but on a global, industrywide scale. As transportation and especially communication technology has improved, many steps in a manufacturing or even a service process may be outsourced, done by foreign labor. That competition affects the U.S. job market as jobs are moved overseas, but it also opens new markets in developing economies. You may be interested in an overseas job, as American companies open offices in Asian, South American, African, and other countries. Globalization affects job markets everywhere.

Micro Factors of Your Job Market

Whether you are employed or self-employed, whether you look forward to going to work every day or dread it, employment determines how you spend most of your waking hours during most of your days. Employment determines your income and thus your lifestyle, your physical well-being, and to a large extent your satisfaction or emotional well-being. Everyone has a different idea about what a “good job” is. That idea may change over a lifetime as circumstances change, but some specific micro factors will weigh on your decisions, including your

- abilities,

- skills,

- knowledge,

- lifestyle choices.

Abilities are innate talents or aptitudes, what you are capable of or good at. Circumstances may inhibit your use of your abilities or may even cause disabilities. However, you often can develop your abilities—and compensate for disabilities—through training or practice. Sometimes you don’t even know what abilities you have until some experience brings them out.

When Tomika says she is “good with people” or when Bryon says that he is a “natural athlete,” they are referring to abilities that will make them better at some jobs than others. Abilities can be developed and may require upkeep; athletic ability, for example, requires regular fitness workouts to really be maintained. You also may find that you lack some abilities, or think you do because you’ve never tried using them.

Usually, by the time you graduate from high school, you are aware of some of your abilities, although you may not be aware of how they may help or hinder you in different jobs. Also, your idea of your abilities relative to others may be skewed by your context. For example, you may be the best writer in your high school, but not compared to a larger pool of more competitive students. Your high school or college career office may be able to help you identify your abilities and skills and applying that knowledge to your career decisions.

Your job choices are not predetermined by your abilities or apparent lack of them. An ability can be developed or used in a way you have not yet imagined. A lack of ability can sometimes be overcome by using other talents to compensate. Thus, ability is a factor in your job decisions, but certainly not the only one. Your knowledge and skills are equally—if not more—important.

Skills and knowledge are learned attributes. A skill is a process that you learn to apply, such as programming a computer, welding a pipe, or making a customer feel comfortable making a purchase. Knowledge refers to your education and experience and your understanding of the contexts in which your skills may be applied.

Education is one way to develop skills and knowledge. In secondary education, a vocational program prepares you to enter the job market directly after high school and focuses on technical skills such as baking, bookkeeping, automotive repair, or building trades. A college preparatory program focuses on developing general skills that you will need to further your formal education, such as reading, writing, research, and quantitative reasoning.

Past high school or a year or two of community college, it is natural to question the value of more education. Tuition is real money and must be earned or borrowed, both of which have costs. There is also the opportunity cost of the wages you could be earning instead.

Education adds to your earning power significantly, however, by raising the price of your labor. The more education you have, the more knowledge and skills you have. The smaller the supply of labor with your particular knowledge and skills, the higher the price your labor can command. This relationship is the rationale for becoming specialized within a career. However, both specialization and versatility may have value in certain job markets, raising the price of your labor.

More education also confers more job mobility—the ability to change jobs when opportunities arise, because your knowledge and skills make you more useful, and thus valuable, in more ways. Your value as a worker or employee enables you to command higher pay for your labor.

Statistics show a consistent relationship between education and earnings. Over a lifetime of work, say about forty to forty-five years, in the United States a person with a college degree will earn over a million dollars more than someone with a high school diploma. According to a recent study,

“There is a positive correlation between higher levels of education and higher earnings for all racial/ethnic groups and for both men and women…The income gap between high school graduates and college graduates has increased significantly over time. The earnings benefit is large enough for the average college graduate to recoup both earnings forgone during the college years and the cost of full tuition and fees in a relatively short period of time.”Sandy Baum and Jennifer Ma, Education Pays: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society (Princeton, NJ: The College Board, 2007).

Not only are you likely to earn more if you are better educated, but you are also more likely to have a job with a pension plan, health insurance, and paid vacations—benefits that add to your total compensation. Although it may seem quite expensive to you now, your college education is definitely worth it: worth the opportunity cost and worth the direct costs of tuition, fees, and books.Sandy Baum and Jennifer Ma, Education Pays: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society (Princeton, NJ: The College Board, 2007).

Your choices will depend on the characteristics and demands of a job and how they fit your unique constellation of knowledge, skills, personality, characteristics, and aptitudes. For example, your knowledge of finance, visual pursuit skills, ability to manage stress and tolerate risk, aptitude for numerical reasoning, enjoyment of competition, and preference to work independently may suit you for employment as a stockbroker or futures trader. Your manual speed and accuracy, verbal comprehension skills, enjoyment of detail work, strong sense of responsibility, desire to work regular hours in a small group setting, and preference for public service may suit you for training as a court stenographer. Your word fluency, social skills, communication skills, organizational skills, preference to work with people, and desire to lead others may suit you for jobs in education or sales. And so on.

Figure 18.3

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Lifestyle choices affect the amount of income you will need to achieve and maintain your lifestyle and the amount of time you will spend earning income. Lifestyle choices thus affect your career path and job choices in key ways. Typically, when you are beginning a career and have few, if any, dependents, you are more willing to sacrifice time and even pay for a job that will enhance your skills and help you to progress along your career path. As a journalist, for example, you may volunteer for an overseas post; or as a nurse you may volunteer for extra rotations. As a computer programmer, you may assist in the development of open source software.

As you advance in your career, and perhaps become more settled in your life—maybe start a family—you are less willing to sacrifice your personal life to your career, and may seek out a job that allows you to earn the income that supports your dependents while not taking away too much of your time.

Your income needs typically increase as you have dependents and are trying to save and accumulate wealth, and then decrease when your dependents are on their own and you have accumulated some wealth. Your sources of income shift as well, from relying on income from labor earlier in your life to relying on income from investments later.

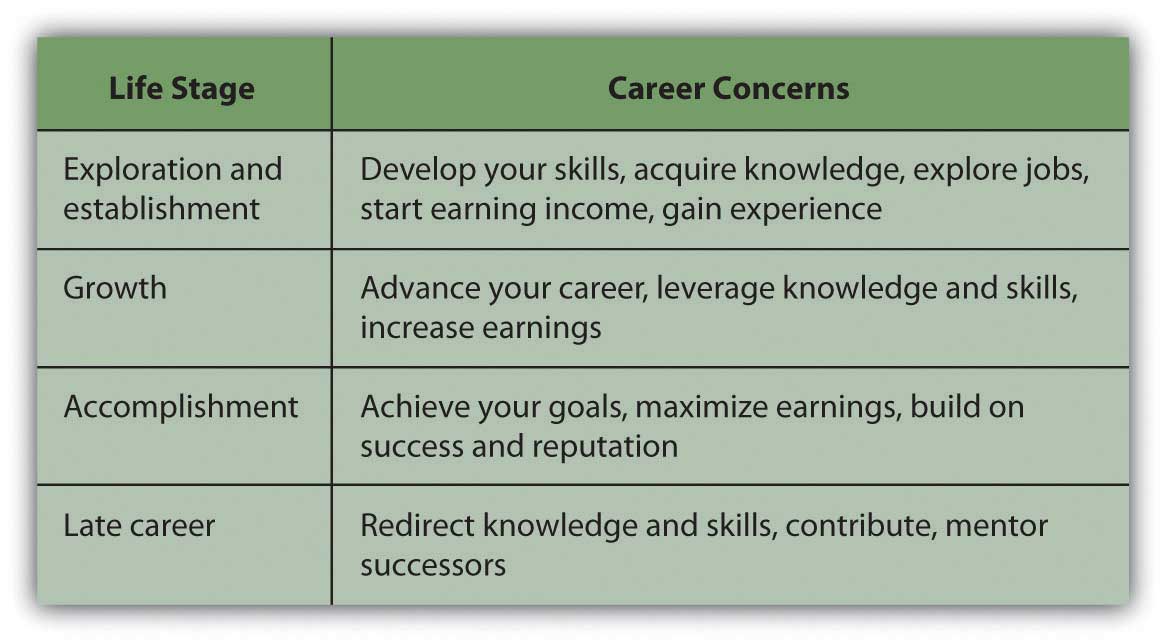

When your family has grown and you once again have fewer dependents, you may really enjoy fulfilling your ambitions, as you have decades of skills and knowledge to apply and the time to apply them. Increasingly, as more people retain their health into older age, they are working in retirement—earning a wage to improve their quality of life or eliminate debt, turning a hobby into a business, or trying something they have always wanted to do. Your life cycle of career development may follow the pattern shown in Figure 18.4 "Lifecycle Career Development".

Figure 18.4 Lifecycle Career Development

Regardless of age, your lifestyle choices will affect your job opportunities and career choices. For example, you may choose to live in a specific geographic region based on its

- rural or urban location,

- proximity to your family or friends,

- differences or similarities to where you grew up,

- cultural or recreational offerings,

- political characteristics,

- climate,

- cost of living.

Sometimes you may choose to sacrifice your lifestyle preferences for your ambitions, and sometimes you may sacrifice your ambitions for your preferences. It’s really a matter of figuring out what matters at the time, while keeping in mind the effect of this decision on the next one.

Key Takeaways

-

Macroeconomic factors affect job markets, including

- economic cycles,

- new technology or obsolescence,

- demographic changes,

- changes in the global economy,

- changes in consumer preferences,

- changes in laws and regulations.

- Job markets are globally competitive.

-

Microeconomic factors influence job and career decisions, including

- abilities or aptitudes,

- skills and knowledge,

- lifestyle choices.

- Microeconomic factors and income needs change over a lifetime and typically correlate with age and stage of life.

- Job and career choices should realistically reflect income needs.

Exercises

- Record in My Notes or your personal finance journal your work history and current thoughts about your future work life. What jobs have you held? In each job, what experience, knowledge, or skills did you acquire or develop? What are your future job preferences, and why do you prefer them? Do you have a planned career path? What potential advantages and opportunities do your preferences or plans offer? What potential disadvantages and costs may your preferences or plans entail?

- Go online to find out the differences in definition between an occupation and a vocation, profession, trade, career, and career path. Which combination of concepts best describes the approach you plan to take to satisfy your needs for income from future employment? Sample the links at http://www.rileyguide.com/careers.html. Choose and record or bookmark the three best online sources of career information for you.

- Take a free online career development aptitude test, such as the one at http://www.careertest.us/Career_Aptitude_Survey.htm. (Note that sites offering free aptitude, personality, or job preference tests often require online registration. You should evaluate the reliability, credibility, and security of any site you use to explore your career preferences.) What personality attributes and personal aptitudes are micro factors that may affect your career choices or your chances of success in a particular job? View the kinds of assessments you may be asked to take as a job applicant or employee at http://www.ppicentral.com/Pdf/Employee_Aptitude_Survey.pdf. What aptitudes are included in the battery of tests that make up the Employee Aptitude Survey? How might an employer use the test results?

- In My Notes or your personal finance journal, list your most important job skills, aptitudes, and preferences on which you plan to expand or build a career. Then list the specific job skills you feel you need to develop further through additional education or experience. How and where will you get those skills and at what cost? Next, describe the lifestyle you hope to support through income from future employment. What aspects of that lifestyle would be easiest for you to modify or sacrifice for your career or income goals?