This is “Investor Behavior”, section 13.1 from the book Individual Finance (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

13.1 Investor Behavior

Learning Objectives

- Identify and describe the biases that can affect investor decision making.

- Explain how framing errors can influence investor decision making.

- Identify the factors that can influence investor profiles.

Rational thinking can lead to irrational decisions in a misperceived or misunderstood context. In addition, biases can cause people to emphasize or discount information or can lead to too strong an attachment to an idea or an inability to recognize an opportunity. The context in which you see a decision, the mental frame you give it (i.e., the kind of decision you determine it to be) can also inhibit your otherwise objective view.Much research has been done in the field of behavioral finance over the past thirty years. A comprehensive text for further reading is by Hersh Shefrin, Beyond Greed and Fear: Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). Learning to recognize your behaviors and habits of mind that act as impediments to objective decision making may help you to overcome them.

Biases

One kind of investor behavior that leads to unexpected decisions is biasA tendency or preference or belief that interferes with objectivity., a predisposition to a view that inhibits objective thinking. Biases that can affect investment decisions are the following:

- Availability

- Representativeness

- Overconfidence

- Anchoring

- Ambiguity aversionHersh Shefrin, Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Financial Behavior and the Psychology of Investing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Availability biasIn finance, an investor’s tendency to base the probability of an event on the availability of information. occurs because investors rely on information to make informed decisions, but not all information is readily available. Investors tend to give more weight to more available information and to discount information that is brought to their attention less often. The stocks of corporations that get good press, for example, claim to do better than those of less publicized companies when in reality these “high-profile” companies may actually have worse earnings and return potential.

RepresentativenessThe practice of stereotyping asset performance, or of assuming commonality of disparate assets based on superficial, stereotypical traits. is decision making based on stereotypes, characterizations that are treated as “representative” of all members of a group. In investing, representativeness is a tendency to be more optimistic about investments that have performed well lately and more pessimistic about investments that have performed poorly. In your mind you stereotype the immediate past performance of investments as “strong” or “weak.” This representation then makes it hard to think of them in any other way or to analyze their potential. As a result, you may put too much emphasis on past performance and not enough on future prospects.

Objective investment decisions involve forming expectations about what will happen, making educated guesses by gathering as much information as possible and making as good use of it as possible. OverconfidenceA bias in which you have too much faith in the precision of your estimates, causing you to underestimate the range of possibilities that actually exist. is a bias in which you have too much faith in the precision of your estimates, causing you to underestimate the range of possibilities that actually exist. You may underestimate the extent of possible losses, for example, and therefore underestimate investment risks.

Overconfidence also comes from the tendency to attribute good results to good investor decisions and bad results to bad luck or bad markets.

AnchoringA bias in which the investor relies too heavily on limited known factors or points of reference. happens when you cannot integrate new information into your thinking because you are too “anchored” to your existing views. You do not give new information its due, especially if it contradicts your previous views. By devaluing new information, you tend to underreact to changes or news and become less likely to act, even when it is in your interest.

Ambiguity aversionA preference for known risks over unknown risks. is the tendency to prefer the familiar to the unfamiliar or the known to the unknown. Avoiding ambiguity can lead to discounting opportunities with greater uncertainty in favor of “sure things.” In that case, your bias against uncertainty may create an opportunity cost for your portfolio. Availability bias and ambiguity aversion can also result in a failure to diversify, as investors tend to “stick with what they know.” For example, in a study of defined contribution retirement accounts or 401(k)s, more than 35 percent of employees had more than 30 percent of their account invested in the employing company’s stock, and 23 percent had more than 50 percent of their retirement account invested in their employer’s stockS. Holden and J. VanDerhei, “401(k) Plan Asset Allocation, Account Balances, and Loan Activity in 2002,” EBRI Issue Brief 261 (2003).—hardly a well-diversified asset allocation.

Framing

FramingThe idea that the presentation or perception of a decision influences the deicision maker. refers to the way you see alternatives and define the context in which you are making a decision.A. Tversky and D. Kahneman, “The Framing Decisions and the Psychology of Choice,” Science 30, no. 211 (1981): 453–58. Your framing determines how you imagine the problem, its possible solutions, and its connection with other situations. A concept related to framing is mental accountingA preference to segregate investment accounts by goals and constraints, rather than to perceive the entire portfolio as a whole.: the way individuals encode, describe, and assess economic outcomes when they make financial decisions.R. Thaler, "Mental Accounting Matters," Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 12, no. 3 (1999): 183–206. In financial behavior, framing can lead to shortsighted views, narrow-minded assumptions, and restricted choices.

Figure 13.1

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Every rational economic decision maker would prefer to avoid a loss, to have benefits be greater than costs, to reduce risk, and to have investments gain value. Loss aversionAn investor’s preference to avoid losses, even when the costs outweigh the benefits, in which case it is not the rational economic choice. refers to the tendency to loathe realizing a loss to the extent that you avoid it even when it is the better choice.

How can it be rational for a loss to be the better choice? Say you buy stock for $100 per share. Six months later, the stock price has fallen to $63 per share. You decide not to sell the stock to avoid realizing the loss. If there is another stock with better earnings potential, however, your decision creates an opportunity cost. You pass up the better chance to increase value in the hopes that your original value will be regained. Your opportunity cost likely will be greater than the benefit of holding your stock, but you will do anything to avoid that loss. Loss aversion is an instance where a rational aversion leads you to underestimate a real cost, leading you to choose the lesser alternative.

Loss aversion is also a form of regret aversion. Regret is a feeling of responsibility for loss or disappointment. Past decisions and their outcomes inform your current decisions, but regret can bias your decision making. Regret can anchor you too firmly in past experience and hinder you from seeing new circumstances. Framing can affect your risk tolerance. You may be more willing to take risk to avoid a loss if you are loss averse, for example, or you may simply become unwilling to assume risk, depending on how you define the context.

Framing also influences how you manage making more than one decision simultaneously. If presented with multiple but separate choices, most people tend to decide on each separately, mentally segregating each decision.Hersh Shefrin, Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Financial Behavior and the Psychology of Investing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). By framing choices as separate and unrelated, however, you may miss making the best decisions, which may involve comparing or combining choices. Lack of diversification or overdiversification in a portfolio may also result.

Investor Profiles

An investor profileA combination of characteristics based on personality traits, life stage, and sources of wealth. expresses a combination of characteristics based on personality traits, life stage, sources of wealth, and other factors. What is your investor profile? The better you can know yourself as an investor, the better investment decisions you can make.

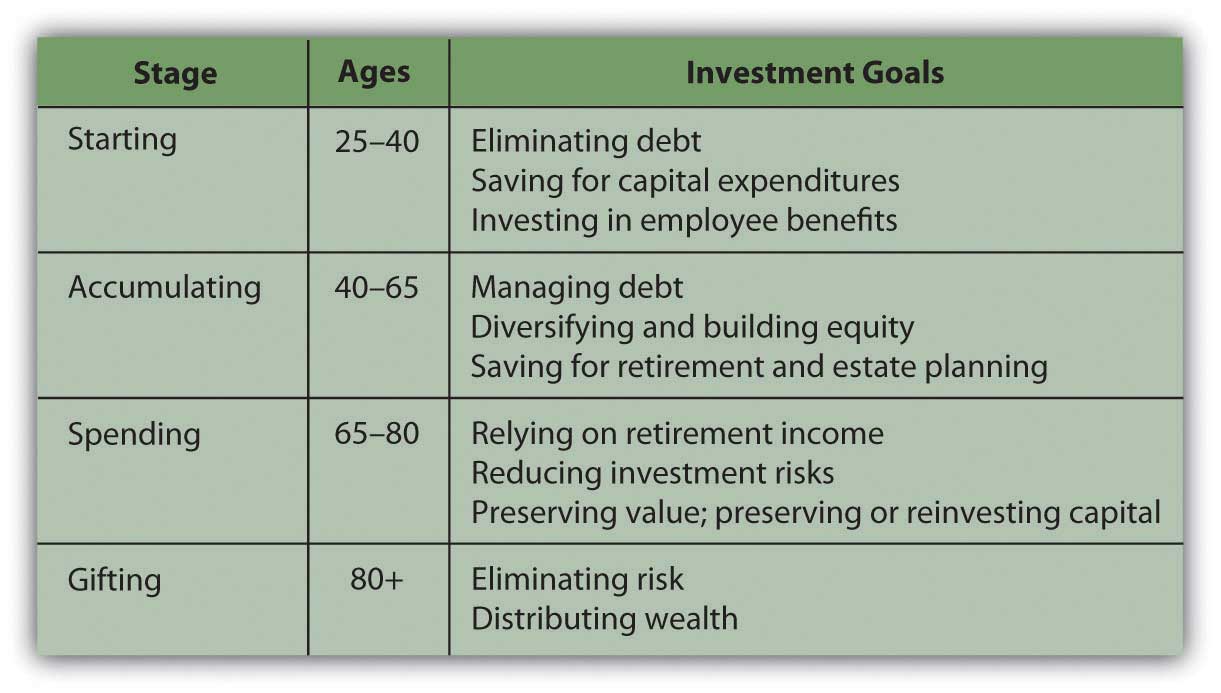

Researchers have identified some features or characteristics of investors that seem to lead to recognizable tendencies.A reference for this discussion is John L. Maginn, Donald L. Tuttle, Jerald E. Pinto, and Dennis W. McLeavey, eds., Managing Investment Portfolios: A Dynamic Process, 3rd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007). For example, stages of life have an effect on goals, views, and decisions, as shown in the examples in Figure 13.2 "Life Stage Profiles".

Figure 13.2 Life Stage Profiles

These “definitions” are fairly loose yet typical enough to think about. In each of these stages, your goals and your risk tolerance—both your ability and willingness to assume risk—change. Generally, the further you are from retirement and the loss of your wage income, the more risk you will take with your investments, having another source of income (your paycheck). As you get closer to retirement, you become more concerned with preserving your investment’s value so that it can generate income when it becomes your sole source of income in retirement, thus causing you to become less risk tolerant. After retirement, your risk tolerance decreases even more, until the very end of your life when you are concerned with dispersing rather than preserving your wealth.

Risk tolerance and investment approaches are affected by more than age and investment stage, however. Studies have shown that the source and amount of wealth can be a factor in attitudes toward investment.John L. Maginn, Donald L. Tuttle, Jerald E. Pinto, and Dennis W. McLeavey, eds., Managing Investment Portfolios: A Dynamic Process, 3rd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007).

Those who have inherited wealth or come to it “passively,” tend to be much more risk averse than those who have “actively” created their own wealth. Entrepreneurs, for example, who have created wealth, tend to be much more willing to assume investment risk, perhaps because they have more confidence in their ability to create more wealth should their investments lose value. Those who have inherited wealth tend to be much more risk averse, as they see their wealth as a windfall that, once lost, they cannot replace.

Active wealth owners also tend to be more active investors, more involved in investment decisions and more knowledgeable about their investment portfolios. They have more confidence in their ability to manage and to make good decisions than do passive wealth owners, who haven’t had the experience to build confidence.

Not surprisingly, those with more wealth to invest tend to be more willing to assume risk. The same loss of value is a smaller proportional loss for them than for an investor with a smaller asset base.

Many personality traits bear on investment behavior, including whether you generally are

- confident or anxious,

- deliberate or impetuous,

- organized or sloppy,

- rebellious or conventional,

- an abstract or linear thinker.

What makes you make the decisions that you make? The more aware you are of the influences on your decisions, the more you can factor them in—or out—of the investment process.

Key Takeaways

- Traditional assumptions about economic decision making posit that financial behavior is rational and markets are efficient. Behavioral finance looks at all the factors that cause realities to depart from these assumptions.

-

Biases that can affect investment decisions are the following:

- Availability

- Representativeness

- Overconfidence

- Anchoring

- Ambiguity aversion

-

Framing refers to the way you see alternatives and define the context in which you are making a decision. Examples of framing errors include the following:

- Loss aversion

- Choice segregation

- Framing is a kind of mental accounting—the way individuals classify, characterize, and evaluate economic outcomes when they make financial decisions.

-

Investor profiles are influenced by the investor’s

- life stage,

- personality,

- source of wealth.

Exercises

- Debate rational theory with classmates. How rational or nonrational (or irrational) do you think people’s economic decisions are? What are some examples of efficient and inefficient markets, and how did people’s behavior create those situations? In My Notes or your personal finance journal record some examples of your nonrational economic behavior. For example, describe a situation in which you decreased the value of one of your assets rather than maintaining or increasing its value. In what circumstances are you likely to pay more for something than it is worth? Have you ever bought something you did not want or need just because it was a bargain? Do you tend to avoid taking risks even when the odds are good that you will not take a loss? Have you ever had a situation in which the cost of deciding not to buy something proved greater than buying it would have cost? Have you ever made a major purchase without considering alternatives? Have you ever regretted a financial decision to such an extent that the disappointment has influenced all your subsequent decisions?

- Angus has always held shares of a big oil company’s stock and has never thought about branching out to other companies or industries in the energy sector. His investment has done well in the past, proving to him that he is making the right decision. Angus has been reading about fundamental changes predicted for the energy sector, but he decides to stick with what he knows. In what ways is Angus’s investment behavior irrational? What kinds of investor biases does his decision making reveal?

- Complete the interactive investor profile questionnaire at https://www11.ingretirementplans.com/webcalc/jsp/ws/typeOfInvestor.jsp. According to this instrument, what kinds of investments should you consider? Then refine your understanding of your investor profile by filling out the more comprehensive interview questions at http://www.karenibach.com/files/2493/SEI%20Questionaire.pdf. In My Notes or your personal finance journal, on the basis of what you have learned, write an essay profiling yourself as an investor. You may choose to post your investor profile and compare it with those of others taking this course. Specifically, how do you think your profile will assist you and your financial advisor or investment advisor in planning your portfolio?

- Using terms and concepts from behavioral finance, how might you evaluate the consumer or investor behavior shown in the following photos? In what ways might these economic behaviors be regarded as rational? In what contexts might these behaviors become irrational?

Figure 13.3

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Figure 13.4

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Figure 13.5

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation