This is “Social Networks”, section 7.4 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.4). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.4 Social Networks

Learning Objectives

- Know what social networks are, be able to list key features, and understand how they are used by individuals, groups, and corporations.

- Understand the difference between major social networks MySpace, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

- Recognize the benefits and risks of using social networks.

- Be aware of trends that may influence the evolution of social networks.

Social networksAn online community that allows users to establish a personal profile and communicate with others. Large public social networks include MySpace, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Google’s Orkut. have garnered increasing attention as established networks grow and innovate, new networks emerge, and value is demonstrated. The two most dominant public social networks are Facebook and LinkedIn, sites often described as the personal and professional networks, respectively. But there are also a host of third-party networks where firms can “roll their own” private networks. Such services include Ning, Lithium, and SelectMinds.

Social networks allow you to set up a profile, share content, comment on what others have shared, and follow the updates of particular users, groups, firms, and brands that may also be part of those networks. Many also are platforms for the deployment of third-party applications (not surprisingly, social games dominate).

Hundreds of firms have established pages on Facebook and communities on LinkedIn, and these are now legitimate customer- and client-engagement platforms. If a customer has decided to press the “like” button of a firm’s Facebook page, corporate posts can appear in their news feed, gaining more user attention than the often-ignored ads that run on the sides of social networks. These posts, and much of the other activity that takes place on social networks, spread via feed (or news feed). Pioneered by Facebook but now adopted by most services, feeds provide a timely list of the activities of and public messages from people, groups, and organizations that an individual has an association with.

Feeds are inherently viralIn this context, information or applications that spread rapidly between users.. By seeing what others are doing on a social network, and by leveraging the power of others to act as word-of-mouth evangelists, feeds can rapidly mobilize populations, prompt activism, and offer low-cost promotion and awareness of a firm’s efforts. Many firms now see a Facebook presence and social engagement strategy as vital. Facebook’s massive size and the viral power of spreading the word through feeds, plus the opportunity to invite commentary and engage consumers in a dialogue, rather than a continual barrage of promotion, is changing the way that firms and customers interact (indeed, you’ll hear many successful social media professionals declare that social media is more about conversations with customers than about advertising-style promotion).

Feeds are also controversial. Many users have reacted negatively to a public broadcast of their online activity, and feed mismanagement can create accusation of spamming, public relations snafus, and user discontent and can potentially open up a site to legal action. Facebook initially dealt with a massive user outcry at the launch of feeds, and the site also faced a subsequent backlash when its Beacon service broadcast user purchases without first explicitly asking their permission and during attempts to rework its privacy policy and make Facebook data more public and accessible. (See Chapter 8 "Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph" for more details.)

Social Networks

The foundation of a social network is the user profile, but utility goes beyond the sort of listing found in a corporate information directory. Typical features of a social network include support for the following:

- Detailed personal profiles

- Affiliations with groups (e.g., alumni, employers, hobbies, fans, health conditions, causes); with individuals (e.g., specific “friends”); and with products, firms, and other organizations

- Private messaging and public discussions

- Media sharing (text, photos, video)

- Discovery-fueling feeds of recent activity among members (e.g., status changes, new postings, photos, applications installed)

- The ability to install and use third-party applications tailored to the service (games, media viewers, survey tools, etc.), many of which are also social and allow others to interact

While a Facebook presence has become a must-have for firms (see Chapter 8 "Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph"), LinkedIn has become a vital tool for many businesses and professionals. LinkedIn boasted a nearly $9 billion valuation after its spring 2011 IPO (some say that price is a sign of a tech bubble and is far too high for a firm with less than $16 million in profits the previous year).S. Woo, L. Cowan, and P. Tam, “LinkedIn IPO Soars, Feeding Web Boom,” Wall Street Journal, May 20, 2011. Regardless of the valuation, the site’s growth has been spectacular, and its influence is threatening recruiting sites like Monster.com and CareerBuilder.M. Boyle, “Recruiting: Enough to Make a Monster Tremble,” BusinessWeek, June 25, 2009.

LinkedIn was conceived from the start as a social network for business users. On LinkedIn, members post profiles and contact information, list their work history, and can be “endorsed” by others on the network. It’s sort of like having your résumé and letters of recommendation in a single location. Users can pose questions to members of their network, engage in group discussions, and ask for introductions through mutual contacts. The site has also introduced a variety of additional services, including messaging, information sharing, and news and content curation—yes, LinkedIn will help you find stuff you’re likely to be most interested in (wasn’t that Google’s job?). The firm makes money from online ads, premium subscriptions, and hiring tools for recruiters.

Active members find the site invaluable for maintaining professional contacts, seeking peer advice, networking, and even recruiting. Starbucks manager of enterprise staffing has stated that LinkedIn is “one of the best things for finding midlevel executives.”R. King, “No Rest for the Wiki,” BusinessWeek, March 12, 2007. Such networks are also putting increasing pressure on firms to work particularly hard to retain top talent. While once HR managers fiercely guarded employee directories for fear that a list of talent may fall into the hands of rivals, today’s social networks make it easy for anyone to gain a list of a firm’s staff, complete with contact information and a private messaging channel.

Corporate Use of Social Networks

Social networks have also become organizational productivity tools. Employees have organized thousands of groups using publicly available social networking sites because similar tools are not offered by their firms.E. Frauenheim, “Social Revolution,” Workforce Management, October 2007. Assuming a large fraction of these groups are focused on internal projects, this demonstrates a clear pent-up demand for corporate-centric social networks (and creates issues as work dialogue moves outside firm-supported services).

Many firms are choosing to meet this demand by implementing internal social network platforms that are secure and tailored to firm needs. At the most basic level, these networks have supplanted the traditional employee directory. Social network listings are easy to update and expand, and employees are encouraged to add their own photos, interests, and expertise to create a living digital identity.

Firms such as Deloitte, Dow Chemical, and Goldman Sachs have created social networks for “alumni” who have left the firm or retired. These networks can be useful in maintaining contacts for future business leads, rehiring former employees (20 percent of Deloitte’s experienced hires are so-called boomerangs, or returning employees), or recruiting retired staff to serve as contractors when labor is tight.R. King, “Social Networks: Execs Use Them Too,” BusinessWeek, November 11, 2006. Maintaining such networks will be critical in industries like IT and health care that are likely to be plagued by worker shortages for years to come.

Social networking can also be important for organizations like IBM, where some 42 percent of employees regularly work from home or client locations. IBM’s social network makes it easier to locate employee expertise within the firm, organize virtual work groups, and communicate across large distances.W. Bulkley, “Playing Well with Others,” Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2007. As a dialogue catalyst, a social network transforms the public directory into a font of knowledge sharing that promotes organization flattening and value-adding expertise sharing.

While IBM has developed their own social network platforms, firms are increasingly turning to third-party vendors like SelectMinds (adopted by Deloitte, Dow Chemical, and Goldman Sachs) and LiveWorld (adopted by Intuit, eBay, the NBA, and Scientific American). Ning allows anyone to create a social network and currently hosts over 2.3 million separate online communities.K. Swisher, “Ning CEO Gina Bianchini to Step Down—Becomes an EIR at Andreessen Horowitz,” AllThingsD, March 15, 2010. However, with robust corporate tools now offered by LinkedIn, we might see proprietary, in-house efforts start to migrate there over time.

A Little Too Public?

As with any type of social media, content flows in social networks are difficult to control. Embarrassing disclosures can emerge from public systems or insecure internal networks. Employees embracing a culture of digital sharing may err and release confidential or proprietary information. Networks could serve as a focal point for the disgruntled (imagine the activity on a corporate social network after a painful layoff). Publicly declared affiliations, political or religious views, excessive contact, declined participation, and other factors might lead to awkward or strained employee relationships. Users may not want to add a coworker as a friend on a public network if it means they’ll expose their activities, lives, persona, photos, sense of humor, and friends as they exist outside of work. And many firms fear wasted time as employees surf the musings and photos of their peers.

All are advised to be cautious in their social media sharing. Employers are trawling the Internet, mining Facebook, and scouring YouTube for any tip-off that a would-be hire should be passed over. A word to the wise: those Facebook party pics, YouTube videos of open mic performances, or blog postings from a particularly militant period might not age well and may haunt you forever in a Google search. Think twice before clicking the upload button! As Socialnomics author Erik Qualman puts it, “What happens in Vegas stays on YouTube (and Flickr, Twitter, Facebook…).”

Firms have also created their own online communities to foster brainstorming and customer engagement. Dell’s IdeaStorm.com forum collects user feedback and is credited with prompting line offerings, such as the firm’s introduction of a Linux-based laptop.D. Greenfield, “How Companies Are Using I.T. to Spot Innovative Ideas,” InformationWeek, November 8, 2008. At MyStarbucksIdea.com, the coffee giant has leveraged user input to launch a series of innovations ranging from splash sticks that prevent spills in to-go cups, to new menu items. Both IdeaStorm and MyStarbucksIdea run on a platform offered by Salesforce.com that not only hosts these sites but also provides integration into Facebook and other services. Starbucks (the corporate brand with the most Facebook “fans”) has extensively leveraged the site, using Facebook as a linchpin in the “Free Pastry Day” promotion (credited with generating one million in-store visits in a single day) and promotion of the firm’s AIDS-related (Starbucks) RED campaign, which garnered an astonishing three hundred ninety million “viral impressions” through feeds, wall posts, and other messaging.J. Gallaugher and S. Ransbotham, “Social Media and Customer Dialog Management at Starbucks,” MIS Quarterly Executive 9, no. 4 (December 2010): 197—212.

Social Networks and Health Care

Dr. Daniel Palestrant often shows a gruesome slide that provides a powerful anecdote for Sermo, the social network for physicians that he cofounded and where he serves as CEO. The image is of an eight-inch saw blade poking through both sides of the bloodied thumb of a construction worker who’d recently arrived in a hospital emergency room. A photo of the incident was posted to Sermo, along with an inquiry on how to remove the blade without damaging tissue or risking a severed nerve. Within minutes replies started coming back. While many replies advised to get a hand surgeon, one novel approach suggested cutting a straw lengthwise, inserting it under the teeth of the blade, and sliding the protected blade out while minimizing further tissue tears.M. Schulder, “50on50: Saw Blade through Thumb. What Would You Do?” CNN, November 4, 2009. The example illustrates how doctors using tools like Sermo can tap into the wisdom of crowds to save thumbs and a whole lot more.

Sermo is a godsend to remote physicians looking to gain peer opinion on confounding cases or other medical questions. The American Medical Association endorsed the site early on (although they failed to renew during a raucous debate on health care reform),The AMA and Sermo have since broken ties; see B. Comer, “Sermo and AMA Break Ties,” Medical Marketing and Media, July 9, 2009. and the Nature scientific journals experimented with a “Discuss on Sermo” button alongside the online versions of their medical articles. Doctors are screened and verified to maintain the integrity of participants. Members leverage the site both to share information with each other and to engage in learning opportunities provided by pharmaceutical companies and other firms. Institutional investors also pay for special access to poll Sermo doctors on key questions, such as opinions on pending FDA drug approval. Sermo posts can send valuable warning signals on issues such as disease outbreaks or unseen drug side effects. And doctors have also used the service to rally against insurance company policy changes.

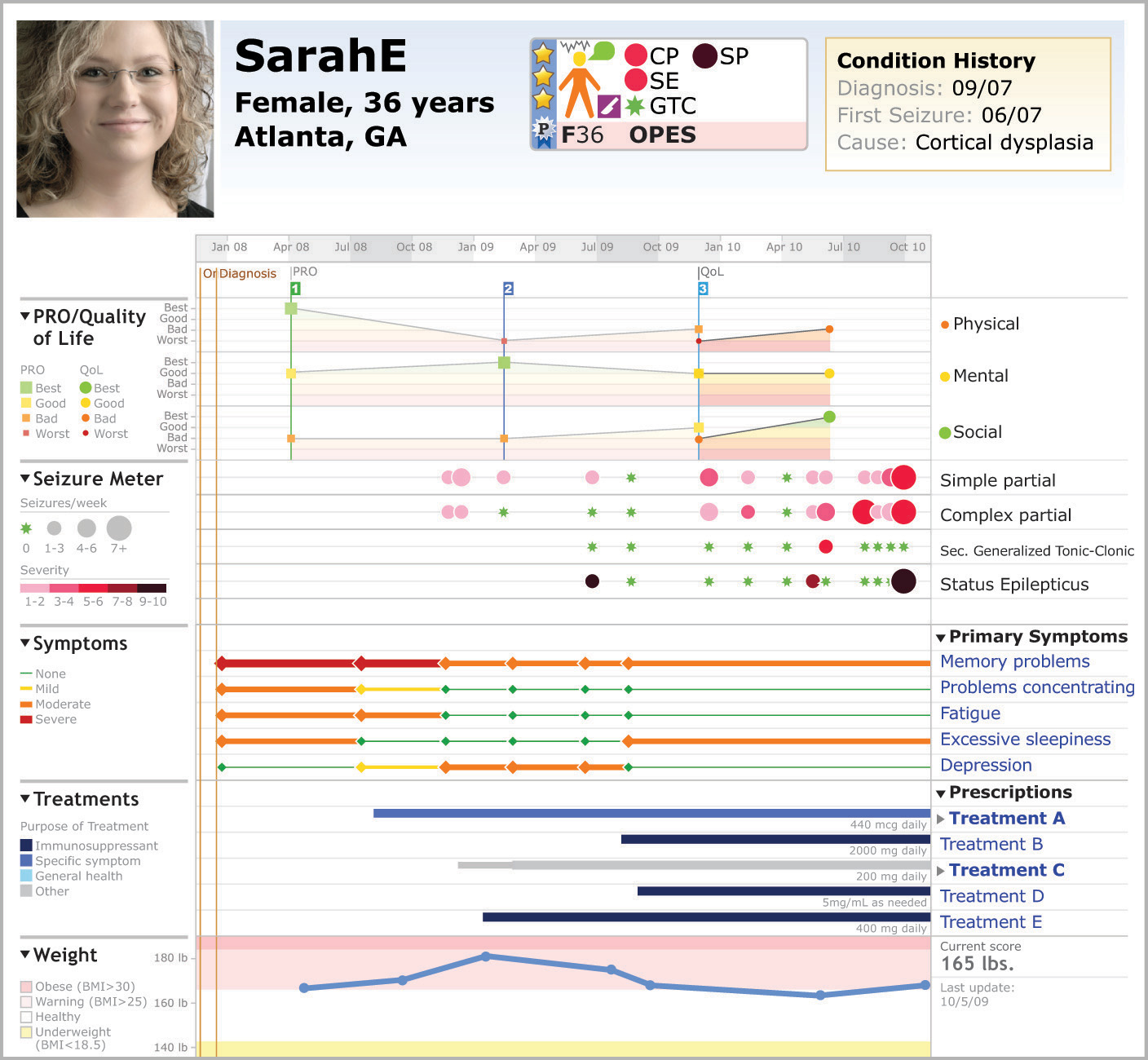

Figure 7.1

These are some of the rich health monitoring and sharing tools available on PatientsLikeMe. Note that treatments, symptoms, and quality-of-life measures can be tracked over time.

Source: PatientsLikeMe, 2011.

While Sermo focuses on the provider side of the health care equation, a short walk from the firm’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, headquarters will bring one to PatientsLikeMe (PLM), a social network empowering chronically ill patients across a wide variety of disease states. The firm’s “openness policy” is in contrast to privacy rules posted on many sites and encourages patients to publicly track and post conditions, treatments, and symptom variation over time, using the site’s sophisticated graphing and charting tools. The goal is to help others improve the quality of their own care by harnessing the wisdom of crowds.

Todd Small, a multiple sclerosis sufferer, used the member charts and data on PLM to discover that his physician had been undermedicating him. After sharing site data with his doctor, his physician verified the problem and upped the dose. Small reports that the finding changed his life, helping him walk better than he had in a decade and a half and eliminating a feeling that he described as being trapped in “quicksand.”T. Goetz, “Practicing Patients,” New York Times Magazine, March 23, 2008. In another example of PLM’s people power, the site ran its own clinical trial—like experiment to rapidly investigate promising claims that the drug Lithium could improve conditions for ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) patients. While community efforts did not support these initial claims, a decision was arrived at in months, whereas previous efforts to marshal researchers and resources to focus on the relatively rare disease would have taken many years, even if funding could be found.J. Kane, R. Fichman, J. Gallaugher, and J. Glaser, “Community Relations 2.0,” Harvard Business Review, November 2009.

Both Sermo and PatientsLikeMe are start-ups that are still exploring the best way to fund their efforts for growth and impact. Regardless of where these firms end up, it should be clear from these examples that social media will remain a powerful force on the health care landscape.

Key Takeaways

- Electronic social networks help individuals maintain contacts, discover and engage people with common interests, share updates, and organize as groups.

- Modern social networks are major messaging services, supporting private one-to-one notes, public postings, and broadcast updates or “feeds.”

- Social networks also raise some of the strongest privacy concerns, as status updates, past messages, photos, and other content linger, even as a user’s online behavior and network of contacts changes.

- Network effects and cultural differences result in one social network being favored over others in a particular culture or region.

- Information spreads virally via news feeds. Feeds can rapidly mobilize populations, and dramatically spread the adoption of applications. The flow of content in social networks is also difficult to control and sometimes results in embarrassing public disclosures.

- Feeds have a downside and there have been instances where feed mismanagement has caused user discontent, public relations problems, and the possibility of legal action.

- The use of public social networks within private organizations is growing, and many organizations are implementing their own, private, social networks.

- Firms are also setting up social networks for customer engagement and mining these sites for customer ideas, innovation, and feedback.

Questions and Exercises

- Visit the major social networks (MySpace, Facebook, LinkedIn). What distinguishes one from the other? Are you a member of any of these services? Why or why not?

- How are organizations like Deloitte, Goldman Sachs, and IBM using social networks? What advantages do they gain from these systems?

- What factors might cause an individual, employee, or firm to be cautious in their use of social networks?

- How do you feel about the feed feature common in social networks like Facebook? What risks does a firm expose itself to if it leverages feeds? How might a firm mitigate these kinds of risks?

- What sorts of restrictions or guidelines should firms place on the use of social networks or the other Web 2.0 tools discussed in this chapter? Are these tools a threat to security? Can they tarnish a firm’s reputation? Can they enhance a firm’s reputation? How so?

- Why do information and applications spread so quickly within networks like Facebook? What feature enables this? What key promotional concept (described in Chapter 2 "Strategy and Technology: Concepts and Frameworks for Understanding What Separates Winners from Losers") does this feature foster?

- Why are some social networks more popular in some nations than others?

- Investigate social networks on your own. Look for examples of their use for fostering political and social movements; for their use in health care, among doctors, patients, and physicians; and for their use among other professional groups or enthusiasts. Identify how these networks might be used effectively, and also look for any potential risks or downside. How are these efforts supported? Is there a clear revenue model, and do you find these methods appropriate or potentially controversial? Be prepared to share your findings with your class.