This is “Customer Profiling and Behavioral Targeting”, section 14.7 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.2). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.7 Customer Profiling and Behavioral Targeting

Learning Objectives

- Be familiar with various tracking technologies and how they are used for customer profiling and ad targeting.

- Understand why customer profiling is both valuable and controversial.

- Recognize steps that organizations can take to help ease consumer and governmental concerns.

Advertisers are willing to pay more for ads that have a greater chance of reaching their target audience, and online firms have a number of targeting tools at their disposal. Much of this targeting occurs whenever you visit a Web site, where a behind-the-scenes software dialogue takes place between Web browser and Web server that can reveal a number of pieces of information, including IP address, the type of browser used, the computer type, its operating system, and unique identifiers, called cookiesA line of identifying text, assigned and retrieved by a given Web server and stored by your browser..

And remember, any server that serves you content can leverage these profiling technologies. You might be profiled not just by the Web site that you’re visiting (e.g., nytimes.com), but also by any ad networks that serve ads on that site (e.g., Platform-A, DoubleClick, Google AdSense, Microsoft adCenter).

IP addresses are leveraged extensively in customer profiling. An IP address not only helps with geolocation, it can also indicate a browser’s employer or university, which can be further matched with information such as firm size or industry. IBM has used IP targeting to tailor its college recruiting banner ads to specific schools, for example, “There Is Life After Boston College, Click Here to See Why.” That campaign garnered click-through rates ranging from 5 to 30 percentM. Moss, “These Web Sites Know Who You Are,” ZDNet UK, October 13, 1999. compared to average rates that are currently well below 1 percent for untargeted banner ads. DoubleClick once even served a banner that included a personal message for an executive at then-client Modem Media. The ad, reading “Congratulations on the twins, John Nardone,” was served across hundreds of sites, but was only visible from computers that accessed the Internet from the Modem Media corporate network.M. Moss, “These Web Sites Know Who You Are,” ZDNet UK, October 13, 1999.

The ability to identify a surfer’s computer, browser, or operating system can also be used to target tech ads. For example, Google might pitch its Chrome browser to users detected running Internet Explorer, Firefox, or Safari; while Apple could target Mac ads just to Windows users.

But perhaps the greatest degree of personalization and targeting comes from cookies. Visit a Web site for the first time, and in most cases, a dialogue between server and browser takes place that goes something like this:

Server: Have I seen you before?

Browser: No.

Server: Then take this unique string of numbers and letters (called a cookie). I’ll use it to recognize you from now on.

The cookie is just a line of identifying text assigned and retrieved by a given Web server and stored on your computer by your browser. Upon accepting this cookie your browser has been tagged, like an animal. As you surf around the firm’s Web site, that cookie can be used to build a profile associated with your activities. If you’re on a portal like Yahoo! you might type in your zip code, enter stocks that you’d like to track, and identify the sports teams you’d like to see scores for. The next time you return to the Web site, your browser responds to the server’s “Have I see you before?” question with the equivalent of “Yes, you know me;,” and it presents the cookie that the site gave you earlier. The site can then match this cookie against your browsing profile, showing you the weather, stock quotes, sports scores, and other info that it thinks you’re interested in.

Cookies are used for lots of purposes. Retail Web sites like Amazon use cookies to pay attention to what you’ve shopped for and bought, tailoring Web sites to display products that the firm suspects you’ll be most interested in. Sites also use cookies to keep track of what you put in an online “shopping cart,” so if you quit browsing before making a purchase, these items will reappear the next time you visit. And many Web sites also use cookies as part of a “remember me” feature, storing user IDs and passwords. Beware this last one! If you check the “remember me” box on a public Web browser, the next person who uses that browser is potentially using your cookie, and can log in as you!

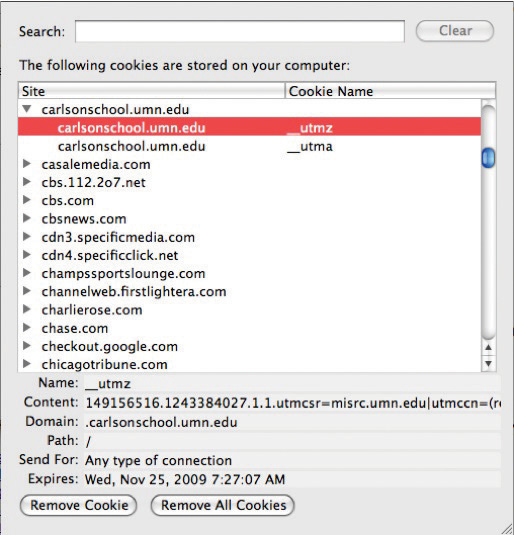

An organization can’t read cookies that it did not give you. So businessweek.com can’t tell if you’ve also got cookies from forbes.com. But you can see all of the cookies in your browser. Take a look and you’ll almost certainly see cookies from dozens of Web sites that you’ve never visited before. These are third-party cookiesSometimes called “tracking cookies” and are served by ad networks or other customer profiling firms. Tracking cookies are used to identify users and record behavior across multiple Web sites. (sometimes called tracking cookies), and they are usually served by ad networks or other customer profiling firms.

Figure 14.12

The Preferences setting in most Web browsers allows you to see its cookies. This browser has received cookies from several ad networks, media sites, and the University of Minnesota Carlson School of Management.

By serving and tracking cookies in ads shown across partner sites, ad networks can build detailed browsing profiles that include sites visited, specific pages viewed, duration of visit, and the types of ads you’ve seen and responded to. And that surfing might give an advertising network a better guess at demographics like gender, age, marital status, and more. Visit a new parent site and expect to see diaper ads in the future, even when you’re surfing for news or sports scores!

But What If I Don’t Want a Cookie!

If all of this creeps you out, remember that you’re in control. The most popular Web browsers allow you to block all cookies, block just third-party cookies, purge your cookie file, or even ask for your approval before accepting a cookie. Of course, if you block cookies, you block any benefits that come along with them, and some Web site features may require cookies to work properly. Also note that while deleting a cookie breaks a link between your browser and that Web site, if you supply identifying information in the future (say by logging into an old profile), the site might be able to assign your old profile data to the new cookie.

While the Internet offers targeting technologies that go way beyond traditional television, print, and radio offerings, none of these techniques is perfect. Since users are regularly assigned different IP addresses as they connect and disconnect from various physical and Wi-Fi networks, IP targeting can’t reliably identify individual users. Cookies also have their weaknesses. They’re assigned by browsers and associated with a given user’s account on that computer. That means that if several people use the same browser on the same computer without logging on to that machine as separate users, then all their Web surfing activity may be mixed into the same cookie profile. (One solution is to create different log-in accounts on that computer. Your PC will then keep separate cookies for each account.) Some users might also use different browsers on the same machine or use different computers. Unless a firm has a way to match up these different cookies assigned across browsers (say by linking cookies on separate machines to a single log-in used at multiple locations), then a site may be working with multiple, incomplete profiles.

Key Takeaways

- The communication between Web browser and Web server can identify IP address, the type of browser used, the computer type, its operating system, time and date of access, and duration of Web page visit, and can read and assign unique identifiers, called cookies—all of which can be used in customer profiling and ad targeting.

- An IP address not only helps with geolocation; it can also be matched against other databases to identify the organization providing the user with Internet access (such as a firm or university), that organization’s industry, size, and related statistics.

- A cookie is a unique line of identifying text, assigned and retrieved by a given Web server and stored on a computer by the browser, that can be used to build a profile associated with your Web activities.

- The most popular Web browsers allow you to block all cookies, block just third-party cookies, purge your cookie file, or even ask for your approval before accepting a cookie.

Questions and Exercises

- Give examples of how the ability to identify a surfer’s computer, browser, or operating system can be used to target tech ads.

- Describe how IBM targeted ad delivery for its college recruiting efforts. What technologies were used? What was the impact on click-through rates?

- What is a cookie? How are cookies used? Is a cookie a computer program? Which firms can read the cookies in your Web browser?

- Does a cookie accurately identify a user? Why or why not?

- What is the danger of checking the “remember me” box when logging in to a Web site using a public computer?

- What’s a third-party cookie? What kinds of firms might use these? How are they used?

- How can users restrict cookie use on their Web browsers? What is the downside of blocking cookies?

- Work with a faculty member and join the Google Online Marketing Challenge (held in the spring of every year—see http://www.google.com/onlinechallenge). Google offers ad credits for student teams to develop and run online ad campaigns for real clients and offers prizes for winning teams. Some of the experiences earned in the Google Challenge can translate to other ad networks as well; and first-hand client experience has helped many students secure jobs, internships, and even start their own businesses.