This is “Act II: Netflix and the Shift from Mailing Atoms to Streaming Bits”, section 4.3 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.2). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.3 Act II: Netflix and the Shift from Mailing Atoms to Streaming Bits

Learning Objectives

- Understand the shift from atoms to bits, and how this is impacting a wide range of industries.

- Recognize the various key issues holding back streaming video models.

- Know the methods that Netflix is using to attempt to counteract these challenges.

Nicholas Negroponte, the former head of MIT’s Media Lab and founder of the One Laptop per Child effort, wrote a now-classic essay on the shift from atoms to bitsThe idea that many media products are sold in containers (physical products, or atoms) for bits (the ones and zeros that make up a video file, song, or layout of a book). As the Internet offers fast wireless delivery to TVs, music players, book readers, and other devices, the “atoms” of the container aren’t necessary. Physical inventory is eliminated, offering great cost savings.. Negroponte pointed out that most media products are created as bits—digital files of ones and zeros that begin their life on a computer. Music, movies, books, and newspapers are all created using digital technology. When we buy a CD, DVD, or even a “dead tree” book or newspaper, we’re buying physical atoms that are simply a container for the bits that were created in software—a sound mixer, a video editor, or a word processor.

The shift from atoms to bits is realigning nearly every media industry. Newspapers struggle as readership migrates online and once-lucrative classified ads and job listings shift to the bits-based businesses of Craigslist, Monster.com, and LinkedIn. Apple dominates music sales, selling not a single “atom” of physical CDs, while most of the atom-selling “record store” chains of a decade ago are bankrupt. Amazon jumped into the atoms-to-bits shift when it developed the Kindle digital reader. Who needs to kill a tree, spill ink, fill a warehouse, and roll a gas-guzzling truck to get you a book? Kindle can slurp your purchases through the air and display them on a device lighter than any college textbook. When the Kindle was released, many thought it to be an expensive, niche product for gadget lovers, but in less than four years, the firm was selling more electronic books than print titles,M. Hamblen, “Amazon: E-Books Now Outsell Print Books,” ComputerWorld, May 19, 2011. and in both unit sales and total revenue, the Kindle had become the best-selling product ever sold on Amazon.com.A. Golsalves, “Amazon Says Kindle Best Selling Product Ever,” InformationWeek, December 27, 2010.

There’s a clear potential upside to the Netflix model as it shifts from mailing atoms to streaming bits: it will eliminate a huge chunk of costs associated with shipping and handling. Postage represents one-third of the firm’s expenses. A round-trip DVD mailing, even at the deep discounts Netflix receives from the U.S. Postal Service, runs about eighty cents, while the bandwidth and handling costs to send bits to a TV set are around a nickel.B. McCarthy, “Netflix, Inc.” (remarks, J. P. Morgan Global Technology, Media, and Telecom Conference, Boston, MA, May 18, 2009). At some point, if postage goes away, Netflix may be in a position to offer even greater profits to its studio suppliers and to make more money itself, too. But Netflix became a profitable business by handling the atoms of DVDs, and the streaming space is crowded with a host of rivals offering consumers a dizzying array of options. Victory is far from certain.

Video is already going digital, but Netflix became a profitable business by handling the atoms of DVDs. The question is, will the atoms to bits shift crush Netflix and render it as irrelevant as Hastings did Blockbuster? Or can Reed pull off yet another victory and recast his firm for the day that DVDs disappear?

Concerns over the death of the DVD and the relentless arrival of new competitors are probably the main cause for Netflix’s stock volatility these past few years. Through the first half of 2011, the firm’s growth, revenue, and profit graphs all go up and to the right, but the stock has experienced wild swings as pundits have mostly guessed wrong about the firm’s imminent demise (one well-known Silicon Valley venture capitalist even referred to the firm as “an ice cube in the sun,”M. Copeland, “Netflix Lives! Video Downloads Haven’t Made the DVD-by-Mail Business Obsolete,” Fortune, April 21, 2008. a statement Netflix countered with six years of record-breaking growth and profits). The troughs on the Netflix stock graph have proven great investment opportunities for the savvy. Netflix broke all previous growth and earnings records and posted its lowest customer churn ever, even as a deep recession and the subprime crisis hammered many other firms. But even the most bullish investor can see that there’s no stopping the inevitable shift from atoms to bits, and the firm’s share price swings continue. When the DVD dies, the high-tech shipping and handling infrastructure that Netflix has relentlessly built will be rendered worthless. The question is, can Hastings pull off yet another victory and recast Netflix for the day that DVDs disappear, or will the atoms-to-bits shift decimate his firm’s hard-earned competitive advantage and render his firm as irrelevant as Blockbuster?

Reed Hastings has always expected the firm would migrate from atoms to bits. He also prepared the public for a first-cut service that was something less than we’d expect from the long tail poster child. When speaking about the launch of the firm’s Internet video streaming offering in January 2007, Hastings said it would be “underwhelming.” The two biggest limitations of this initial service? As we’ll see below, not enough content, and figuring out how to squirt the bits to a television.

Access to Content

First the content. Three years after the launch of Netflix streaming option (enabled via a “Watch Now” button next to movies that can be viewed online), only 17,000 videos were offered, just 17 percent of the firm’s long tail. And not the best 17 percent. While the number of titles available for streaming by Netflix has steadily increased, acquiring content has been a significant challenge. Netflix is able to send out physical DVDs in the United States due to a Supreme Court ruling known as the “First Sale Doctrine.” Even if studios charge Netflix full price for their discs, they can’t prevent the firm from sending purchased discs to subscribers. But “First Sale Doctrine” applies to the disc, not the media, so Netflix can’t offer unlimited streaming without separate licenses.D. Roth, “Netflix Everywhere: Sorry Cable, You’re History,” Wired, September 21, 2009. It’s not just studio reluctance or fear of piracy. There are often complicated legal issues involved in securing the digital distribution rights for all of the content that makes up a movie. Music, archival footage, and performer rights may all hold up a title from being available under “Watch Now.” The 2007 Writers Guild strike occurred largely due to negotiations over digital distribution, showing just how troublesome these issues can be.

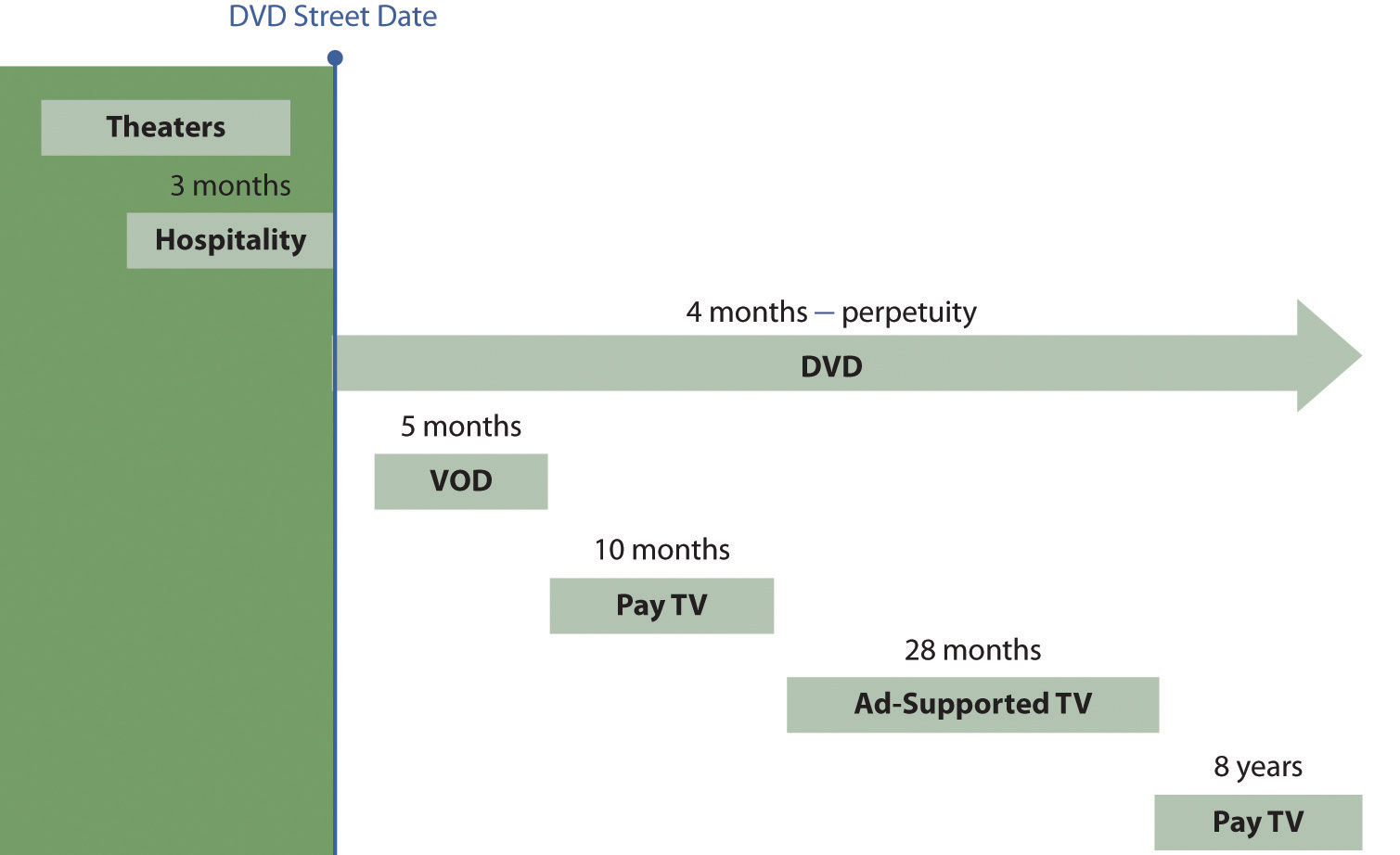

Add to that the exclusivity contracts negotiated by key channels, in particular the so-called premium television networks. Film studios release their work in a system called windowingIndustry practice whereby content (usually a motion picture) is available to a given distribution channel for a specified time period or “window,” usually under a different revenue model (e.g., ticket sale, purchase, license fee).. Content is available to a given distribution channel (in theaters, through hospitality channels like hotels and airlines, on DVD, via pay-per-view, via pay cable, then broadcast commercial TV) for a specified time window, usually under a different revenue model (ticket sales, disc sales, license fees for broadcast). Windows controlled by pay television channels can be particularly challenging, since many have negotiated exclusive access to content as they strive to differentiate themselves from one another. This exclusivity means that even when a title becomes available for streaming by Netflix, it may disappear when a pay TV window opens up. If HBO or Showtime has an exclusive for a film, it’s pulled from the Netflix streaming service until the exclusive pay TV time window closes. A 2008 partnership with the Starz network helped provide access to some content locked up inside pay television windows, and deals with individual networks and studios allow for streaming of current-season shows.S. Portnoy, “Netflix News: Starz Catalog Added to Online Service, Streaming to PS3, Xbox 360 through PlayOn Beta Software,” ZDNet, October 2, 2008, http://blogs.zdnet.com/home-theater/?p=120. But the firm still has a long way to go before the streaming tail seems comparably long when compared against its disc inventory.

Figure 4.7 Film Release Windows

Source: Reproduced by permission of Netflix, Inc. Copyright © 2009, Netflix, Inc. All rights reserved.

Even those studios that embrace the audience-finding and revenue-sharing advantages of Netflix don’t want to undercut higher-revenue early windows. Fox, Universal, and Warner have all demanded that Netflix delay sending DVDs to customers until twenty-eight days after titles go on sale. In exchange, Netflix has received guarantees that these studios will offer more content for digital streaming.

There’s also the influence of the king of DVD sales: Wal-Mart. The firm accounts for about 40 percent of DVD sales—a scale that delivers a lot of the bargaining power it has used to “encourage” studios to hold content from competing windows or to limit offering digital titles at competitive pricing during the peak new release period.R. Grover, “Wal-Mart and Apple Battle for Turf,” BusinessWeek, August 31, 2006. Apparently, Wal-Mart isn’t ready to yield ground in the shifts from atoms to bits, either. In February 2010, the retail giant spent an estimated $100 million to buy the little-known video streaming outfit VUDU.B. Stone, “Wal-Mart Adds Clout to Streaming,” New York Times, February 22, 2010. Wal-Mart’s negotiating power with studios may help it gain special treatment for VUDU. As an example, VUDU was granted exclusive high-definition streaming rights for the hit movie Avatar, offering the title online the same day the DVD appeared for sale.J. Jacobson, “VUDU/Wal-Mart Gets Avatar HD Streaming Exclusive,” Electronic House, April 22, 2010.

Studios may also be wary of the increasing power Netflix has over product distribution, and as such, they may be motivated to keep rivals around. Studios have granted Blockbuster more favorable distribution terms than Netflix. While the bankrupt firm was bought out by Dish Network and remains a shadow of its former self, in many cases, Blockbuster can now distribute DVDs the day of release instead of waiting nearly a month, as Netflix does.J. Birchall, “Blockbuster Strikes Deal to Ensure DVD Supply,” Financial Times, April 8, 2010. Studios are likely concerned that Netflix may be getting so big that it will one day have Wal-Mart-like negotiating leverage.

Controlling rising licensing costs presents a further challenge. Streaming costs are growing rapidly, with Netflix financials indicating the firm’s cost of acquiring streaming content has steadily risen, from $48 million in 2008 to $64 million in 2009, then to a whopping $406 million in 2010. The Starz deal cost the firm about $30 million, but some estimates suggest that renewal might require ten times that amount.G. Szala, “Analysts Opine on Possible Netflix-Starz Deal Renewal,” Hollywood Reporter, May 10, 2011. Streaming licensing deals are tricky because rates vary widely even when titles are available. Titles might be offered via a flat rate for unlimited streams, a per-stream rate, a rate for a given number of streams, a premium for exclusive content, and various permutations in between. Some vendors have been asking as much as four dollars per stream for more valuable contentD. Rayburn, “Netflix Streaming Costs,” Streaming Media, June/July 2009.—a fee that would quickly erase subscriber profits, making any such titles too costly to add to the firm’s library. Remember, Netflix doesn’t charge more for streaming—it’s built into the price of its flat-rate subscriptions, so these marginal costsThe cost associated with each additional unit produced. could crater earnings.

The Netflix track record for securing streaming deals has also been mixed, with some firms steadfastly refusing to offer Netflix streaming rights. Time Warner’s HBO has thus far tried to keep streaming a perk limited to its own paying subscribers. It offers video-on-demand and HBO Go app access for its cable customers, but refuses to offer current content for streaming via Netflix. Many fear that a Netflix with broad content offerings might prompt cable subscribers to become cord cutters, paying only for Internet access and not cable TV.

One way Netflix can counter rivals with exclusive content is to offer exclusive content of its own. It’s first big-name deal involved paying $100 million for the initial twenty-six-episode exclusive for the series House of Cards, beating out HBO and AMC in a bidding war for the yet-to-be produced show that features Oscar-winner Kevin Spacey and which will be produced by David Fincher (director of The Social Network). It’s a risky move—unlike most of Netflix’s other content, House of Cards hasn’t been produced, so no one knows if it’ll be a hit. And it’s unknown if the prospect of exclusive content bidding wars will prompt more firms to share their content instead of fighting over it. But Netflix’s growing audience size is now comparable to that of the largest cable firms, with some suggesting Netflix is a quasi-network (Netflix now has more subscribers than Showtime and Comcast and is closing in on HBOB. Evangelista, “Netflix Growth Moves It into No. 2 behind HBO,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 26, 2011.). Hastings says he anticipates that Netflix will do more exclusive deals for new content, stating, “We’re willing to do that if we have to, but we think it makes more economic sense for us and pay television [providers like HBO] to share windows.”L. Rose, “Netflix Will Distribute David Fincher’s ‘House of Cards’—It’s Official,” Hollywood Reporter, March 18, 2011.

Supplier Power and Atoms to Bits

The winner-take-all, winner-take-most dynamics of digital distribution can put suppliers at a disadvantage. If firms rely on one channel partner for a large portion of sales, that partner has an upper hand in negotiations. For years, record labels and movie studios complained that Apple’s dominance of iTunes allowed them little negotiating room in price setting. A boycott where NBC temporarily lifted TV shows from iTunes is credited with loosening Apple’s pricing policies. Similarly, when Amazon’s Kindle dominated the e-book reader market, Amazon enforced a $9.99 price on electronic editions, even as publishers lobbied for higher rates. It wasn’t until Apple arrived with a creditable e-book rival in the iPad that Amazon’s leverage was weakened to the point where publishers were allowed to set their own e-book prices.M. Rich and B. Stone, “Publisher Wins Fight with Amazon over E-Books,” New York Times, January 31, 2010.

Taken together, all these content acquisition factors make it clear that shifting the long tail from atoms to bits will be significantly more difficult than buying DVDs and stacking them in a remote warehouse.

But How Does It Get to the TV?

The other major problem lies in getting content to the place where most consumers want to watch it: the living room TV. Netflix’s “Watch Now” button first worked only on Windows PCs. Although the service was introduced in January 2007, the months before were fueled with speculation that the firm would partner with TiVo. Just one month later, TiVo announced its first streaming partner—Amazon.com. At that point Netflix found itself up against a host of rivals that all had a path to the television: Apple had its own hardware solution in Apple TV (not to mention the iPod and iPhone for portable viewing), the cable companies delivered OnDemand through their set-top boxes, and now Amazon had TiVo.

An internal team at Netflix developed a prototype set-top box that Hastings himself supported offering. But most customers aren’t enthusiastic about purchasing yet another box for their set top, the consumer electronics business is brutally competitive, and selling hardware would introduce an entirely new set of inventory, engineering, marketing, distribution, and competitive complexities.

The solution Netflix eventually settled on was to think beyond one hardware alternative and instead recruit others to provide a wealth of choice. The firm developed a software platform and makes this available to manufacturers seeking to build Netflix access into their devices. Today, Netflix streaming is baked into over two hundred consumer electronics products, including televisions and DVD players from LG, Panasonic, Samsung, Sony, Toshiba, and Vizio. The migration to Blu-ray has also helped the firm piggyback its way into the living room. Buy one of the increasing number of Blu-ray players that has partnered with Hastings’s firm and for just eight bucks a month you can get a ticket to the all-you-can-eat Netflix buffet. Netflix streaming is also available on all major video game consoles. A Netflix app for Apple’s iPad was available the day the device shipped, and Android users can get in on the action, too. Even TiVo now streams Netflix. And that internally developed Netflix set-top box? The group was spun out to form Roku, an independent firm that launched their own $99 Netflix streamer.

By working with consumer electronics firms, offering Netflix streaming as a feature or an app, Hastings’s firm has ended up with more television access than either Amazon or Apple, despite the fact that both of these firms got their digital content to the TV set first. Partnerships have helped create distribution breadth, giving Hastings an enviable base through which to grow the video streaming business.

Disintermediation and Digital Distribution

The purchase of NBC/Universal by Comcast, the largest cable television provider in the United States, has consolidated content and distribution in a single firm. The move can be described as both vertical integration (when an organization owns more than one layer of its value chain) and disintermediationRemoving an organization from a firm’s distribution channel. Disintermediation collapses the path between supplier and customer. (removing an organization from a firm’s distribution channel).J. Gallaugher, “E-Commerce and the Undulating Distribution Channel,” Communications of the ACM, July 2002. Disintermediation in the video industry offers two potentially big benefits. First, studios don’t need to share revenue with third parties; they can keep all the money generated through new windows. Also critically important, studios keep the interface with their customers. Remember, in the digital age data is valuable; if another firm sits between a supplier and its customers, the supplier loses out on a key resource for competitive advantage. For more on the value of the data asset in maintaining and strengthening customer relationships, see Chapter 11 "The Data Asset: Databases, Business Intelligence, and Competitive Advantage".

Who’s going to win the race for delivering bits to the television is still very much an uncertain bet. The models all vary significantly. Netflix pioneered unlimited subscription streaming, but Blockbuster and VUDU also offer Netflix-like subscriptions and have copied Hastings’s lead, partnering with consumer electronics makers to bring their services to TV sets. Apple’s iTunes offers video purchases and “rentals” that can also play across PCs and Macs, as well as the firm’s iPod, iPhone, iPad, and Apple TV products. Microsoft also offers an online rental and purchase service via Xbox (yes, this makes Microsoft both a Netflix partner as well as a sort of competitor, a phenomenon often referred to as coopetition, or frenemiesA. Brandenberger and B. Nalebuff, Co-opetition: A Revolution Mindset that Combines Competition and Cooperation: The Game Theory Strategy That’s Changing the Game of Business (New York: Broadway Business, 1997); and S. Johnson, “The Frenemy Business Relationship,” Fast Company, November 25, 2008.). Amazon has expanded its Internet video purchase and rental business with the addition of free streaming for thousands of titles as a perk to those customers paying for its Amazon Prime shipping service. Amazon’s consumer electronics partnerships have also expanded (yes, those vendors are quite promiscuous) and many of the same firms partnering with Netflix also stream Amazon content. And Amazon is getting into the disc-by-mail act, too, acquiring LoveFilm (often described as the “Netflix of Europe”), for some $200 million in early 2011.C. Byrne, “Amazon Acquires LoveFilm, Europe’s Netflix, for Approximately $200 Million,” VentureBeat, January 20, 2011. YouTube now offers thousands of television shows and movies via both ad-supported and rental models, and the firm’s parent has launched Google TV to make television access easier. Facebook has begun to experiment with video streaming, working with Warner Brothers to stream The Dark Knight for a fee of thirty Facebook credits. And the networks and content providers also have their own offerings: many stream content on their own Web sites; Comcast and Verizon have apps that stream content to phones, PCs, and tablets; and Hulu is a joint venture backed by NBC, Fox, and other networks. Hulu offers a basic ad-supported PC streaming service as well as Hulu Plus, a subscription service that offers more content as well as streaming to certain consumer electronics devices. Whether all these efforts are individually sustainable remains to be seen. Many are efforts offered by deep-pocketed rivals that can subsidize experimentation through profits from their primary businesses, so even if efforts are slow to gain traction, a shakeout may take time.

Then there’s the issue of unhappy consumer Internet service providers. Netflix streaming has become so successful that by May 2011, the service had become the largest single source of Internet traffic, displacing the prior leader, BitTorrent. That makes many in Hollywood happy since Netflix streams are legally licensed, while BitTorrent is a platform that many see as supporting piracy. But many Internet service providers aren’t pleased by the growth of streaming, viewing Netflix as a rapidly-expanding, network-clogging traffic hog. Netflix pays its own Internet service providers to connect the firm to the Internet and to support its heavy volume of outbound traffic. But Netflix offers no such payment to the ISPs used by consumers (e.g., your local cable and telephone companies). By spring 2011, Netflix streaming made up nearly 30 percent of all U.S. Internet traffic—a 44 percent increase from just six months earlier.R. Lawler, “Netflix Traffic Now Bigger Than BitTorrent. Has Hollywood Won?,” GigaOM, May 17, 2011. Several ISPs, including Comcast (which also owns content through its purchase of NBC/Universal), AT&T, and Charter, have imposed bandwidth capsA limit, imposed by the Internet service provider (e.g., a cable or telephone company) on the total amount of traffic that a given subscriber can consume (usually per each billing period). that place a ceiling on a customer’s total monthly consumption (users can usually bump up the ceiling, but they have to pay to do it). Today few U.S. users are running into the ceiling, but that may change as more family members sport tablets, smartphones, and other streaming devices and as new, traffic-heavy technologies like Apple’s FaceTime and Microsoft’s Skype become more widely used. In Canada, Netflix has already lowered stream quality to deal with that nation’s more restrictive traffic consumption limits. Netflix hasn’t been shy about sharing its concern on bandwidth caps with the FCC, arguing that caps are really a much higher markup than the incremental cost of Internet transmission and claiming that if caps restrict users then this could stifle innovation.R. Lawler, “Netflix Traffic Now Bigger Than BitTorrent. Has Hollywood Won?,” GigaOM, May 17, 2011. If U.S. bandwidth caps start to limit consumer access to streaming, Netflix could suffer.

No Turning Back

While one day the firm will lose the investment in its warehouse infrastructure, nearly all assets have a limited lifespan. That’s why corporations depreciate assets, writing their value down over time. The reality is that the shift from atoms to bits isn’t flicking on like a light switch; it is a hybrid transition taking place over several years. However, the shift is well under way. Says Hastings, “Streaming is much bigger than DVD for us in terms of hours of viewing, growth, and focus.”E. Schonfeld, “Reed Hastings: Netflix DVD Shipments ‘May Go Down the First Time Ever’ This Quarter,” TechCrunch, May 6, 2011. If the firm can grab long-tail content, broaden distribution options, grow its customer base, and lock them in with the switching costs created by Cinematch (all big “ifs”), it just might cement its position as a key player in a bits-only world.

Is the hybrid strategy a dangerous straddling gambit or a clever expansion that will keep the firm dominant? Netflix really doesn’t have a choice but to try. Hastings already has a long history as one of the savviest strategic thinkers in tech. As the networks say, stay tuned!

Key Takeaways

- The shift from atoms to bits is impacting all media industries, particularly those relying on print, video, and music content. Content creators, middlemen, retailers, consumers, and consumer electronics firms are all impacted.

- Netflix’s shift to a streaming model (from atoms to bits) is limited by access to content and in methods to get this content to televisions.

- Windowing and other licensing issues limit available content, and inconsistencies in licensing rates make profitable content acquisitions a challenge.

Questions and Exercises

- What do you believe are the most significant long-term threats to Netflix? How is Netflix trying to address these threats? What obstacles does the firm face in dealing with these threats?

- Who are the rivals to Netflix’s “Watch Now” effort? Do any of these firms have advantages that Netflix lacks? What are these advantages?

- Why would a manufacturer of DVD players be motivated to offer the Netflix “Watch Now” feature in its products?

- Describe various revenue models available as video content shifts from atoms to bits. What are the advantages and disadvantages to each—for consumers, for studios, for middlemen like television networks and Netflix?

- Wal-Mart backed out of the DVD-by-mail industry. Why does the firm continue to have so much influence with the major film studios? What strategic asset is Wal-Mart leveraging?

- Investigate the firm Red Box. Do you think they are a legitimate threat to Netflix? Why or why not?

- Is Netflix a friend or foe to the studios? Make a list of reasons why they would “like” Netflix, and why studios might be fearful of the firm. What is disintermediation, and what incentives do studios have to try to disintermediate Netflix?

- Why didn’t Netflix vertically integrate and offer its own set top box for content distribution?

- Make a chart of the various firms offering video streaming services. List the pros and cons of each, along with its revenue model. Which efforts do you think will survive a shakeout? Why?

- How big is Facebook compared to Netflix? Do you think that Facebook presents a credible threat to Netflix? Why or why not?

- Investigate the current status of bandwidth caps. Do you think bandwidth caps are fair? Why or why not?

- Investigate Netflix stock price. One of the measures of whether a stock is “expensive” or not is the price-earnings ratio (share price divided by earnings per share). P/Es vary widely, but historic P/Es are about fifteen. What is the current P/E of Netflix? Do you think the stock is fairly valued based on prospects for future growth, earnings, and market dominance? Why or why not? How does the P/E of Netflix compare with that of other well-known firms, both in and out of the technology sector? Arrive in class with examples you are ready to discuss.